Trotula

Trotula can refer to Trotula of Salerno (11th–12th centuries) or the Trotula texts. Trotula of Salerno was a female physician who worked in Salerno, Italy. Several writings about women’s health have been attributed to her, including Diseases of Women, Treatments for Women, and Women’s Cosmetics. In medieval Europe, these texts were a major source for information on women’s health.[1]

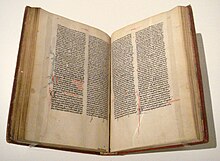

Diseases of Women, Treatments for Women, and Women’s Cosmetics are usually referred to collectively as The Trotula. This is misleading because there is no evidence that Diseases of Women and Women’s Cosmetics were actually written by Trotula; these two texts circulated anonymously until they were combined with Treatments for Women sometime in the thirteenth century. Treatments for Women bears Trotula’s name. By the end of the thirteenth century, the collection of the three texts was known as The Trotula. For the next several hundred years, The Trotula circulated throughout Europe, reaching its greatest popularity in the fourteenth century. Twenty-nine copies exist today.[2]

Only two other texts by Trotula survive. She was one of seven Salerno physicians who contributed to an encyclopedia of medical knowledge, On the Treatment of Illnesses. Her excerpt was later published separately as Practical Medicine According to Trota. These two texts and Treatments for Women are the only three texts bearing Trotula’s name.[3]

Little is known of Trotula's life. She is believed to have been a physician at the so-called School of Salerno. The medieval scholar Caspar Wolff asserted that the Trotula texts were actually written by a man, a freed Roman slave.[4] Two feminist historians, Elizabeth Mason-Hohl and Kate Campbell Hurd-Mead, wrote about Trotula in the 1930s/40s. Both women made false and unsupported elaborations about Trotula’s life, leading to misconceptions that last to this day. It is not known exactly when Trotula lived, if she was married, or if she was an early feminist.[5]

The Trotula

Diseases of Women (De passionibus mulierum curandarum, Trotula Major):

Divided into twenty-seven sections, it describes a variety of female health issues, concentrating on problems with menstruation and child birth. Unlike Treatments for Women, it proposes theoretical explanations of the problems. The theoretical explanations are mainly based on Galen’s gynecological theory. Galen asserts that women are colder than men and unable to “cook” their nutrients; thus they must eliminate excess substance through menstruation. In Galenic gynecology, menstruation is viewed as a healthy and important phenomenon. The author of Diseases of Women describes ways of regulating menstruation at length. The issue of womb movement, another major part of Galenic gynecology, is also discussed in detail. Upward movement of the womb, or “suffocation” of the womb, causes a variety of problems. The author explains that womb suffocation results from an excess of female semen (another Galenic idea) and proposes several possible remedies. Other issues discussed at length are treatment for obstetric fistula and the proper regimen for a newly born child. The author of this text was probably introduced to Galenic gynecology through Arabic medical texts, such as Ibn al-Jazzar's Viaticum.[6]

Treatments for Women:

This text lists treatments for various female issues (and a few male issues as well). Little explanation for the cause of the problem is given; instead, the focus lies on the treatment of the issue. The issues described range from sunburn to infertility. The remedies often involve mixtures of herbs and spices. The treatments listed originate from the Mediterranean oral tradition, rather than Galenic or Arabic texts.[7]

Women’s Cosmetics:

Describes techniques for whitening teeth, dying hair, purifying skin, removing hair, and coloring lips. This text is shorter than the other two. Many of the treatments are of Muslim origin.[8]

References

- ^ Green, Monica: The Trotula, page xi. U. of PA, 2001.

- ^ Green, pages 49-59.

- ^ Green, page 49.

- ^ Rowland, Beryl: Medieval Woman’s Guide to Health, page 3-4. Kent State, 1981.

- ^ Stuard, Susan Mosher (Winter 1975). "Dame Trot". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 1 (2). University of Chicago Press: 537–42. JSTOR 3173063.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); line feed character in|journal=at position 26 (help) - ^ Green, pages 17-25, 65-87.

- ^ Green, pages 89-112.

- ^ Green, pages 113-124.

Further reading

- Rowland, Beryl (1979). "Exhuming Trotula, Sapiens Matrona of Salerno". Florilegium. 1: 42–57. ISSN 0709-5201. PMID 11616980.

- Green, Monica H, ed. (2001). The Trotula: a medieval compendium of women's medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 0-8122-3589-4.

- reviewed at Nutton, Vivian (2003 January). "The Trotula: a medieval compendium of women's medicine" (book review). Medical History. 47 (1): 136–7. PMC 1044789.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- reviewed at Nutton, Vivian (2003 January). "The Trotula: a medieval compendium of women's medicine" (book review). Medical History. 47 (1): 136–7. PMC 1044789.