Worksop Bestiary

| Worksop Bestiary | |

|---|---|

| Morgan Bestiary | |

| |

| Date | ~1185 |

| Principal manuscript(s) | Physiologus |

| Length | 124 pages |

The Worksop Bestiary, also known as the Morgan Bestiary (MS 81), most likely from Lincoln or York, England,[1][2] is an illuminated manuscript created around 1185, containing a bestiary and other compiled medieval Latin texts on natural history. The manuscript has influenced many other bestiaries throughout the medieval world and is possibly part of the same group as the Aberdeen Bestiary, Alnwick Bestiary, St.Petersburg Bestiary, and other similar Bestiaries. Now residing in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, the manuscript has had a long history of church, royal, government, and scholarly ownership.

Description

[edit]The manuscript was made in England around the year 1185.[3] The manuscript consists of 124 pages, 106 of which have circular miniature illuminations measuring 21.5cm high by 15.5cm wide.[4] The manuscript is written in a black letter minuscule book hand.[5] The current binding dates to the nineteenth century.[6][7] The manuscript is considered to be the earliest example of the so-called Transitional Family line of bestiaries. It combines a compilation of the 2nd-century Greek Alexandrian Physiologus bestiary as well as Imago mundi of Honorius Augustodunensis, the Etymologiae of St. Isidore of Seville, extracts from the Book of Genesis, and other works included in various bestiaries of its time.[8] It also contains the text of a sermon on Saint Joseph, which was previously assumed to be written by Saint Augustine.

Style

[edit]Stylistically, the Worksop Bestiary is a part of a larger group of similar "sister" manuscripts all based on the Greek Physiologus. Other very similar manuscripts to the Worksop Bestiary include:

- St.Petersburg manuscript Q.v.V.1[5][9]

- British Library MS. Royal 12 xix.[9][5]

- Ashmole Bestiary MS. 1511[3]

- Aberdeen Bestiary MS. 24[10]

- Harley Leningrade State library's BM. 4751[4]

- Alnwick Bestiary MS.447[11]

In comparison to the Worksop Bestiary, the Alnwick Bestiary (formerly Northumberland Bestiary MS.447)[11] features eight illuminations of Adam's creation and ends with a section on fish that is different from both the Worksop Bestiary or the very similar Bright Royal Library's MS. 12.[12][10] There are similarities in the fish sections of the Worksop Bestiary and the Ashmole Bestiary, but overall, these two manuscripts show very different artistic techniques.[12][10] The newer Radford Bestiary is considered to be a copy of the Worksop Bestiary.[12]

Provenance

[edit]

The book is now held by the Morgan Library & Museum, New York (MS. 81).[6] The manuscript was presented to the Augustinian Worksop Priory Church of Saint Mary and Saint Cuthbert, by Philip Apostolorum, a canon of Lincoln Cathedral, along with a map of the world and many other books, on September 20, 1187.[13] This was intended for use by the monks at the priory.[14] Later owners of the manuscript include the dukes of Hamilton, the Prussian government, as well as the designer William Morris who acquired the book shortly before his death in 1896 for £900. Later, the book was purchased by Richard Bennett of Manchester, from whom the Pierpont Morgan library acquired the text in 1902.[8]

Illumination

[edit]Much like the British Library's MS. Royal 12 manuscript, the Worksop Bestiary features similar content, with extracts from the De imagine mundi, Genesis, Isidore's De pecoribus et iumentis and De Avibus, as well as other sermons that are irrelevant to the bestiary. The manuscript is divided into sections, classifying animals as beasts, birds, and fish, all derived from the Physiologus. Animals are associated with Biblical virtues and vices. Three unique sections of the Worksop Bestiary that can be found in no other known bestiaries include: St. Isidore's De aquis, De terra, and a sermon on Joseph ascribed to St. Augustine.[5]

Beasts

[edit]

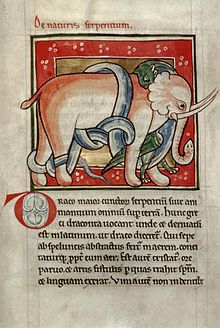

The manuscript often deviates from natural uses of color and form, such as in the illustrations for the unicorn, satyr, and crow, and onager, which are stylistically very similar in their use of unrealistic colors in the Aberdeen Bestiary.[15] For example, the unicorn on 13 recto is illustrated in a deep blue color as it approaches the virgin in the scene, who is depicted as a trap for the hunters to catch the unicorn. Other unnatural features can be seen in the wild donkey which is portrayed as having characteristics attributed to the devil on 19 recto. The same is true of how the wolf is depicted throughout the manuscript as hunters of the Sheep of Christ.[2] The imagery of "evil" animals such as wolves and wild donkeys is in stark comparison to how creatures such as the horse are depicted as symbols of humility as seen on folio 44 verso-45 recto.[1] The deer here is associated with Christ, especially as it trampled as snake as on folio 29 verso to 30 recto.[1] Imaginary animals such as the hydra are also depicted.[1] Sirens which are a mixture of fish, bird, and woman as depicted on folio 16 verso to 17 recto personify lust and were here depicted as luring sailors to their deaths.[1] Symbolism contained in this text such as on 9 verso to 10 recto features an antelope trapped by its horns as a hunter takes advantage of its situation, which the manuscript regards as indicating both vice and temptation.[1] Serpents resembling dragons were also seen as symbols of temptation, vice, and the devil in general as shown on folio 77 verso and 78 recto, which depicts a serpent-like dragon killing an elephant. One realistic element, however, can be seen on 22 verso to 23 recto, where the elephant illumination demonstrates Persians and Indians used wooden towers on the backs of elephants called howdahs during times of battle.[1] Other notable sections such as the beaver indicate that the animal was used for medicinal purposes.[1]

Birds

[edit]The turtle doves depicted on 65 verso to 66 recto were used to model Christian monogamous relations since they mate for life - symbolism of the marriage of Christ and Church.[1] According to 57 verso to 58 recto, bees are considered a type of bird and are regarded as reliable hard workers. On folios 64 verso and 65 recto, there is a section about an unknown type of bird called a 'coot,' which is known for "staying only in one place and remaining very clean", an example that the text claims Christians should model themselves after especially in the regard to the Church.[1] Folio 61 verso-62 recto features birds that represent the Jewish people, hinting at anti-Semitic themes which are repeated throughout this manuscript. Another example is on 67 verso to 68 recto where they are compared to 'sinful' goats that were unable to be converted.[1]

Gallery

[edit]-

Worksop Priory, where the manuscript was first donated to monks housed a majority of its existence.

-

68 Verso-69 Recto Sawfish and Ship: A saw-fish with large wings races alongside a ship. When exhausted, the fish is said to retreat to the sea. The scene represents Christians who are overcome by vice but started off good.

-

19 Verso-20 Recto Ape: The manuscript states when an ape has twins, it loves one and despises the other baby. In times of being hunted, the mother ape shield's her back with her unfavored baby while cradling and protecting her favored baby.

-

12 Verso-13 Recto Unicorn and Mary Scene: Two hunters kill a rare unicorn in a virgin's lap

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Morgan Library". 23 February 2018.

- ^ a b Peart, Thomas Jackson (1955). Animals and Animal Legend in Early Medieval Art, Volume 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- ^ a b Benton, Janetta Rebold (2009). Materials, Methods, and Masterpieces of Medieval Art. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-275-99418-1.

- ^ a b Thomas, Hugh M. (2014). The Secular Clergy in England, 1066-1216. OUP Oxford. p. 312. ISBN 9780191007019.

- ^ a b c d "Manuscript MS 81". Medieval Bestiary. 2011.

- ^ a b "Catalogue description of the Worksop Bestiary" (PDF). Catalogue description. The Pierpont Morgan Library. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Badke, David (January 15, 2011). "Morgan Library, MS M.81 (The Worksop Bestiary)". Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Bestiary Elephant". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ a b Morrison, Grollemond, Elizabeth, Larisa (2019). Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 97, 98. ISBN 978-1606065907.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kline, Naomi Reed (2003). Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851159379.

- ^ a b Millar, Eric G. (1958). A Thirteenth‐Century Bestiary in the Library of Alnwick Castle. Oxford: Roxburghe Club.

- ^ a b c Young, Elizabeth Anastasia (2019). O' Beastly Jew! Allegorical Anti-Judaism in the Thirteenth Century English Bestiaries. Michigan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Knowles, David; London, Vera; Brooke, C.N.L (2001). The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, I 940–1216. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781139430746.

- ^ "Patrons of the Luxury Bestiaries at the End of the Twelfth Century". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Werness, Hope S. (2003). The Continuum Encyclopedia Of Animal Symbolism in Art.

External links

[edit] Media related to Worksop Bestiary - Morgan Library M81 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Worksop Bestiary - Morgan Library M81 at Wikimedia Commons