Yaqut al-Musta'simi

Yaqut al-Musta'simi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | 1298 |

| Known for | Islamic calligraphy |

| Movement | Naskh (script) Thuluth |

| Patron(s) | Al-Musta'sim |

Yaqut al-Musta'simi (also Yakut-i Musta'simi) (died 1298[1]) was a well-known calligrapher[2][3] and secretary of the last Abbasid caliph.

Life and work

Born Abu’l-Majd Jamal al-Din Yaqut, he became known as Yaqut al-Musta‘simi because he served Caliph al-Musta‘sim, the last Abassid caliph. He was probably of Greek origin in Amaseia and carried off when he was very young.[4]

He was a slave in the court of Al-Musta'sim and went on to become a calligrapher in the Royal Court. He spent most of his life in Baghdad and converted to Islam. [5] He studied with the female scholar and calligrapher, Shuhda Bint Al-‘Ibari, who was herself a student in the direct line of Ibn al-Bawwab.[6] During the Mongol invasion of Baghdad (1258), he took refuge in the minaret of a mosque so he could finish his calligraphy practice, while the city was being ransacked. His career, however, flourished under Mongol patronage.[7]

He refined and codified six basic calligraphic styles of the Arabic script.[8] Naskh script was said to have been revealed and taught to the scribe in a vision. He improved on Ibn Muqla's style by replacing the straight cut reed pen with an oblique cut, which resulted in a more elegant script.[9] He developed Yakuti, a handwriting named after him, described as a thuluth of "a particularly elegant and beautiful type."[1]

He taught many students, both Arab and non-Arab. His most celebrated students are Ahmad b. al-Suhrawardi and Yahya al-Sufi.[10]

He became a much-celebrated calligrapher across the Arab-speaking world. His school became the model followed by Persian and Ottoman calligraphers for centuries. In the second half of the 13th-century, he gained the honorific, quiblat al-kuttab [cynosure of the calligraphers]. [11]

His output was prolific. Although, he is said to have copied the Qur'an more than a thousand times,[12] problems with attributing his work, may have contributed to exaggerated estimates.[13] Other sources suggest that he produced 364 copies of the Q'ran.[14] He was the last of the great medieval calligraphers.[15]

Gallery

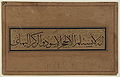

-

Thuluth script, 13th century

See also

References

- ^ a b Efendi, Cafer; Howard Crane (1987). Risāle-i miʻmāriyye: an early-seventeenth-century Ottoman treatise on architecture: facsimile with translation and notes. Brill. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-04-07846-8. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (2004). An Ottoman mentality: the world of Evliya Çelebi. Brill. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-04-13715-8.

- ^ Çelebi, Evli̇ya; Robert Dankoff (2006). Evliya Çelebi in Bitlis: the relevant section of the Seyahatname. Brill. p. 285. ISBN 978-90-04-09242-6. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936, Volume 1. BRILL. p. 1154. ISBN 9789004082656.

YAKUT al-MUSTA'SIMI, Djamal al-DIn Auu 'l-Madjd ... some say he was a Greek from Amasia; he was probably carried off on a razzia while still very young. He was a eunuch.

- ^ Osborn, J.T., Letters of Light: Arabic Script in Calligraphy, Print, and Digital Design, Harvard University Press, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p.

- ^ Robinson, G., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 268; Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S., Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 442

- ^ Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S., Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 442; "Yaqut al-Musta'simi" [Biography], Islamic Arts, Islamic Arts Online (in English):

- ^ Sözen, Metin; İlhan Akşit (1987). The evolution of Turkish art and architecture. Haşet Kitabevi.

- ^ Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S., Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 442; Sajoo, A.B., A Companion to Muslim Cultures, I.B.Tauris, 2011, p. 148

- ^ Sajoo, A.B., A Companion to Muslim Cultures, I.B.Tauris, 2011, p. 148; Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S., Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 442

- ^ Türk ve İslâm Eserleri Müzesi, The Art of the Qurʼan: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 2016, p. 80

- ^ Knappert, Jan (2005). Swahili culture, Book 2. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-6109-3.

- ^ Mansour, N., Sacred Script: Muhaqqaq in Islamic Calligraphy, I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 88n

- ^ Islamic Arts, Islamic Arts Online (in English):

- ^ Robinson, G., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 268