Isospin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

| Flavour in particle physics |

|---|

| Flavour quantum numbers |

|

| Related quantum numbers |

|

| Combinations |

|

| Flavour mixing |

In nuclear physics and particle physics, isospin (isotopic spin, isobaric spin) is a quantum number related to the strong interaction. Particles that are affected equally by the strong force but have different charges (e.g. protons and neutrons) can be treated as being different states of the same particle with isospin values related to the number of charge states.[1]

Although it does not have the units of angular momentum and is not a type of spin, the formalism that describes it is mathematically similar to that of angular momentum in quantum mechanics, which means it can be coupled in the same manner. For example, a proton-neutron pair can be coupled in a state of total isospin 1 or 0.[2] It is a dimensionless quantity and the name derives from the fact that the mathematical structures used to describe it are very similar to those used to describe the intrinsic angular momentum (spin).

This term was derived from isotopic spin, a confusing term to which nuclear physicists prefer isobaric spin, which is more precise in meaning. Isospin symmetry is a subset of the flavour symmetry seen more broadly in the interactions of baryons and mesons. Isospin symmetry remains an important concept in particle physics, and a close examination of this symmetry historically led directly to the discovery and understanding of quarks and of the development of Yang–Mills theory.

Motivation for isospin

Isospin was introduced by Werner Heisenberg in 1932[3] to explain symmetries of the then newly discovered neutron:

- The mass of the neutron and the proton are almost identical: they are nearly degenerate, and both are thus often called nucleons. Although the proton has a positive electric charge, and the neutron is neutral, they are almost identical in all other aspects.

- The strength of the strong interaction between any pair of nucleons is the same, independent of whether they are interacting as protons or as neutrons.

Thus, isospin was introduced as a concept well before the development in the 1960s of the quark model which provides our modern understanding. The specific designation isospin however, was introduced by Eugene Wigner in 1937.[4]

Protons and neutrons were then grouped together as nucleons because they both have nearly the same mass and interact in nearly the same way, if the electromagnetic interaction is neglected. It was convenient to treat them as being different states of the same particle.

When constructing a physical theory of nuclear forces, one could simply assume that it does not depend on isospin, although the total isospin should be conserved.

Similarly to a spin 1⁄2 particle, which has two states, protons and neutrons were said to be of isospin 1⁄2. The proton and neutron were then associated with different isospin projections I3 = +1⁄2 and −1⁄2 respectively.

These considerations would also prove useful in the analysis of meson-nucleon interactions after the discovery of the pions in 1947. The three pions (

π+

,

π0

,

π−

) could be assigned to an isospin triplet with I = 1 and I3 = +1, 0 or −1. By assuming that isospin was conserved by nuclear interactions, the new mesons were more easily accommodated by nuclear theory.

As further particles were discovered, they were assigned into isospin multiplets according to the number of different charge states seen: 2 doublets I = 1⁄2 of K mesons (

K−

,

K0

),(

K+

,

K0

), a triplet I = 1 of Sigma baryons (

Σ+

,

Σ0

,

Σ−

), a singlet I = 0 Lambda baryon (

Λ0

), a quartet I = 3⁄2 Delta baryons (

Δ++

,

Δ+

,

Δ0

,

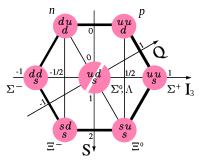

Δ−

), and so on. This multiplet structure was combined with strangeness in Murray Gell-Mann's eightfold way, ultimately leading to the quark model and quantum chromodynamics.

Modern understanding of isospin

Observation of the light baryons (those made of up, down and strange quarks) lead us to believe that some of these particles are so similar in terms of their strong interactions that they can be treated as different states of the same particle. In the modern understanding of quantum chromodynamics, this is because up and down quarks are very similar in mass, and have the same strong interactions. Particles made of the same numbers of up and down quarks have similar masses and are grouped together.

For example, the particles known as the Delta baryons—baryons of spin 3⁄2 made of a mix of three up and down quarks—are grouped together because they all have nearly the same mass (approximately 1232 MeV/c2), and interact in nearly the same way.

However, because the up and down quarks have different charges (2⁄3 e and −1⁄3 e respectively), the four Deltas also have different charges (

Δ++

(uuu),

Δ+

(uud),

Δ0

(udd),

Δ−

(ddd)). These Deltas could be treated as the same particle and the difference in charge being due to the particle being in different states. Isospin was devised as a parallel to spin to associate an isospin projection (denoted I3) to each charged state. Since there were four Deltas, four projections were needed.

Because isospin was modeled on spin, the isospin projections were made to vary in increments of 1 and to have four increments of 1, you needed an isospin value of 3⁄2 (giving the projections I3 = 3⁄2, 1⁄2, −1⁄2, −3⁄2). Thus, all the Deltas were said to have isospin I = 3⁄2 and each individual charge had different I3 (e.g. the

Δ++

was associated with I3 = +3⁄2). In the isospin picture, the four Deltas and the two nucleons were thought to be the different states of two particles. In the quark model, the Deltas can be thought of as the excited states of the nucleons.

After the quark model was elaborated, it was noted that the isospin projection was related to the up and down quark content of particles. The relation is

where nu and nd are the numbers of up and down quarks respectively, and n

u

and n

d

are the numbers of up and down antiquarks respectively.

By this, the value of I3 of the nucleons proton (symbol p) and neutron (symbol n) is determined by their quark composition, uud for the proton and udd for the neutron.

Isospin symmetry

In quantum mechanics, when a Hamiltonian has a symmetry, that symmetry manifests itself through a set of states that have the same energy; that is, the states are degenerate. In particle physics, the near mass-degeneracy of the neutron and proton points to an approximate symmetry of the Hamiltonian describing the strong interactions. The neutron does have a slightly higher mass due to isospin breaking; this is due to the difference in the masses of the up and down quarks and the effects of the electromagnetic interaction. However, the appearance of an approximate symmetry is still useful, since the small breakings can be described by a perturbation theory, which gives rise to slight differences between the near-degenerate states.

SU(2)

Heisenberg's contribution was to note that the mathematical formulation of this symmetry was in certain respects similar to the mathematical formulation of spin, whence the name "isospin" derives. To be precise, the isospin symmetry is given by the invariance of the Hamiltonian of the strong interactions under the action of the Lie group SU(2). The neutron and the proton are assigned to the doublet (the spin-1⁄2, 2, or fundamental representation) of SU(2). The pions are assigned to the triplet (the spin-1, 3, or adjoint representation) of SU(2). Though, there is a difference from the theory of spin: the group action does not preserve flavor.

Like the case for regular spin, the isospin operator I is vector-valued: it has three components Ix, Iy, Iz which are coordinates in the same 3-dimensional vector space where the 3 representation acts. Note that it has nothing to do with the physical space, except similar mathematical formalism. Isospin is described by two quantum numbers: I, the total isospin, and I3, an eigenvalue of the Iz projection for which flavor states are eigenstates, not an arbitrary projection as in the case of spin. In other words, each I3 state specifies certain flavor state of a multiplet. The third coordinate (z), to which the "3" subscript refers, is chosen due to notational conventions which relate bases in 2 and 3 representation spaces. Namely, for the spin-1⁄2 case, components of I are equal to Pauli matrices divided by 2 and Iz = 1⁄2 τ3, where

- .

While the forms of these matrices are the isomorphic to those of spin, these Pauli matrices only acts within the Hilbert space of isospin, not that of spin, and therefore is common to denote them with τ rather than σ to avoid confusion.

The power of isospin symmetry and related methods such as the Eightfold Way come from the observation that families of particles with similar masses tend to correspond to the invariant subspaces associated with the irreducible representations of the Lie algebra 𝖘𝖚(2). In this context, an invariant subspace is spanned by basis vectors which correspond to particles in a family. Under the action of the Lie algebra 𝖘𝖚(2), which generates rotations in isospin space, elements corresponding to definite particle states or superpositions of states can be rotated into each other, but can never leave the space (since the subspace is in fact invariant). This is reflective of the symmetry present. The fact that unitary matrices will commute with the Hamiltonian means that the physical quantities calculated do not change even under unitary transformation. In the case of isospin, this machinery is used to reflect the fact that the strong force behaves the same under the exchange of the up and down quark (and by extension the exchange of the proton and the neutron).

Relationship to flavor

The discovery and subsequent analysis of additional particles, both mesons and baryons, made it clear that the concept of isospin symmetry could be broadened to an even larger symmetry group, now called flavor symmetry. Once the kaons and their property of strangeness became better understood, it started to become clear that these, too, seemed to be a part of an enlarged symmetry that contained isospin as a subgroup. The larger symmetry was named the Eightfold Way by Murray Gell-Mann, and was promptly recognized to correspond to the adjoint representation of SU(3). To better understand the origin of this symmetry, Gell-Mann proposed the existence of up, down and strange quarks which would belong to the fundamental representation of the SU(3) flavor symmetry.

Although isospin symmetry is very slightly broken, SU(3) symmetry is more badly broken, due to the much higher mass of the strange quark compared to the up and down. The discovery of charm, bottomness and topness could lead to further expansions up to SU(6) flavour symmetry, but the very large masses of these quarks makes such symmetries almost useless.[clarification needed] In modern applications, such as lattice QCD, isospin symmetry is often treated as exact while the heavier quarks must be treated separately.

Quark content and isospin

Up and down quarks each have isospin I = 1⁄2, and isospin 3-components (I3) of 1⁄2 and −1⁄2 respectively. All other quarks have I = 0. In general

Hadron nomenclature

Hadron nomenclature is based on isospin.[5][failed verification]

- Particles of isospin 3⁄2 can only be made by a mix of three u and d quarks (Delta baryons).

- Particles of isospin 1 are made of a mix of two u and d quarks (Pi mesons, Rho mesons, Sigma baryons with one heavier quark, etc.).

- Particles of isospin 1⁄2 can be made of a mix of three u and d quarks (nucleons) or from one u or d quark with heavier quarks (K mesons, D mesons, Xi baryons, etc.)

- Particles of isospin 0 can be made of one u and one d quark (Eta mesons, Omega mesons, Lambda baryons, etc.), or from no u or d quarks at all (Omega baryons, Phi mesons, etc.), with heavier quarks in all cases.

Isospin symmetry of quarks

In the framework of the Standard Model, the isospin symmetry of the proton and neutron are reinterpreted as the isospin symmetry of the up and down quarks. Technically, the nucleon doublet states are seen to be linear combinations of products of 3-particle isospin doublet states and spin doublet states. That is, the (spin-up) proton wave function, in terms of quark-flavour eigenstates, is described by[1]

and the (spin-up) neutron by

Here, is the up quark flavour eigenstate, and is the down quark flavour eigenstate, while and are the eigenstates of . Although these superpositions are the technically correct way of denoting a proton and neutron in terms of quark flavour and spin eigenstates, for brevity, they are often simply referred to as "uud" and "udd". Note also that the derivation above assumes exact isospin symmetry and is modified by SU(2)-breaking terms.

Similarly, the isospin symmetry of the pions are given by:

Weak isospin

Isospin is similar to, but should not be confused with weak isospin. Briefly, weak isospin is the gauge symmetry of the weak interaction which connects quark and lepton doublets of left-handed particles in all generations; for example, up and down quarks, top and bottom quarks, electrons and electron neutrinos. By contrast (strong) isospin connects only up and down quarks, acts on both chiralities (left and right) and is a global (not a gauge) symmetry.

Gauged isospin symmetry

Attempts have been made to promote isospin from a global to a local symmetry. In 1954, Chen Ning Yang and Robert Mills suggested that the notion of protons and neutrons, which are continuously rotated into each other by isospin, should be allowed to vary from point to point. To describe this, the proton and neutron direction in isospin space must be defined at every point, giving local basis for isospin. A gauge connection would then describe how to transform isospin along a path between two points.

This Yang–Mills theory describes interacting vector bosons, like the photon of electromagnetism. Unlike the photon, the SU(2) gauge theory would contain self-interacting gauge bosons. The condition of gauge invariance suggests that they have zero mass, just as in electromagnetism.

Ignoring the massless problem, as Yang and Mills did, the theory makes a firm prediction: the vector particle should couple to all particles of a given isospin universally. The coupling to the nucleon would be the same as the coupling to the kaons. The coupling to the pions would be the same as the self-coupling of the vector bosons to themselves.

When Yang and Mills proposed the theory, there was no candidate vector boson. J. J. Sakurai in 1960 predicted that there should be a massive vector boson which is coupled to isospin, and predicted that it would show universal couplings. The rho mesons were discovered a short time later, and were quickly identified as Sakurai's vector bosons. The couplings of the rho to the nucleons and to each other were verified to be universal, as best as experiment could measure. The fact that the diagonal isospin current contains part of the electromagnetic current led to the prediction of rho-photon mixing and the concept of vector meson dominance, ideas which led to successful theoretical pictures of GeV-scale photon-nucleus scattering.

Although the discovery of the quarks led to reinterpretation of the rho meson as a vector bound state of a quark and an antiquark, it is sometimes still useful to think of it as the gauge boson of a hidden local symmetry[6]

Notes

- ^ a b Greiner & Müller 1994

- ^ Povh, Bogdan; Klaus, Rith; Scholz, Christoph; Zetsche, Frank (2008) [1993]. "2". Particles and Nuclei. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-540-79367-0.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 77: 1–11. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...77....1H. doi:10.1007/BF01342433.

- ^ Wigner, E. (1937). "On the Consequences of the Symmetry of the Nuclear Hamiltonian on the Spectroscopy of Nuclei". Physical Review. 51 (2): 106–119. Bibcode:1937PhRv...51..106W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.51.106.

- ^

C. Amsler; et al. (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: Naming scheme for hadrons" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667: 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bando, M.; Kugo, T.; Uehara, S.; Yamawaki, K.; Yanagida, T. (1985). "Is the ρ Meson a Dynamical Gauge Boson of Hidden Local Symmetry?". Physical Review Letters. 54 (12): 1215–1218. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..54.1215B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.1215. PMID 10030967.

References

- Greiner, W.; Müller, B. (1994). Quantum Mechanics: Symmetries (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3540580805.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Itzykson, C.; Zuber, J.-B. (1980). Quantum Field Theory. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-032071-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffiths, D. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Nuclear Structure and Decay Data - IAEA Nuclides' Isospin

Nuclear Structure and Decay Data - IAEA Nuclides' Isospin

![{\displaystyle I_{\mathrm {3} }={\frac {1}{2}}\left[\left(n_{\mathrm {u} }-n_{\mathrm {\bar {u}} })-(n_{\mathrm {d} }-n_{\mathrm {\bar {d}} }\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b7d30a972f39268c712a210450a733022041797a)