Pitched battle: Difference between revisions

Nbutterell (talk | contribs) m Grammar and media edits |

Nbutterell (talk | contribs) Edits to the late Modern era. |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

== Late Modern era == |

== Late Modern era == |

||

{{stack|[[Image:Zuluchargegutt.jpg|thumb|150px|Zulu warriors charging.]]}}Firearms and artillery dominated pitched battles during the late Modern era as technological improvements such as rifling improved the reliability and accuracy of the weapons. The efficacy of firearms increased dramatically during the 18<sup>th</sup> century with the introduction of rifling for enhanced range and accuracy, cartridge ammunition and magazines. As a result, most armies during this period would strictly deploy firearm infantry.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Breeze|first=John|url=|title=Ballistic trauma : a practical guide|date=|publisher=Cham|others=Jowan Penn-Barwell, Damian D. Keene, David J. O'Reilly, Jeyasankar Jeyanathan, Peter F. Mahoney|year=2017|isbn=978-3-319-61364-2|edition=Fourth edition|location=Switzerland|pages=8|oclc=1008749437}}</ref> Notable exceptions to this would be in [[Colonisation of Africa|colonial Africa]] where native armies would still employ close quarter fighting to some success, such as at the battle of Isandlwana in 1879 between the [[Zulu Kingdom|Zulu Empire]] and the [[British Empire|British]].<ref name=":12" /> The mobility and accuracy of artillery was also improved with rifling and sophisticated reload mechanisms and would be utilised to great effect alongside infantry throughout the 19<sup>th</sup> century.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kiley|first=Kevin|url=|title=Artillery of the Napoleonic Wars|date=|publisher=Frontline Books|year=2017|isbn=978-1-84832-954-6|location=|pages=546-548|oclc=1245235071}}</ref> Furthermore, cavalry would continue to be an effective force for pitched battles during this period as they were implemented to harass infantry formations and artillery positions. These tactics would remain in warfare until developments in technology would make pitched battles redundant by the [[World War I|First World War]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Whitman|first=James Q.|url=|title=The verdict of battle : the law of victory and the making of modern war|date=2012|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-06811-7|location=Cambridge, Mass.|pages=213-214|oclc=815276601}}</ref> |

|||

{{stack|[[Image:Zuluchargegutt.jpg|thumb|150px|Zulu warriors charging.]]}} |

|||

===Battle of Isandlwana=== |

===Battle of Isandlwana=== |

||

{{main|Battle of Isandlwana}} |

{{main|Battle of Isandlwana}} |

||

The Zulu army usually deployed in its well known "buffalo horns" formation. The attack layout was composed of three elements:<ref>Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 45–126</ref> |

The Battle of Isandlwana was fought between the Zulu Empire and the British Empire on the 22nd of January 1879. This pitched battle saw the implementation of superior tactics to overwhelm a technologically superior force.<ref name=":12" /> The Zulu army usually deployed in its well known "buffalo horns" formation. The attack layout was composed of three elements:<ref>Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 45–126</ref> |

||

# '''the "horns" or flanking right and left wing elements''' to encircle and pin the enemy. Usually these were the greener troops. |

# '''the "horns" or flanking right and left wing elements''' to encircle and pin the enemy. Usually these were the greener troops. |

||

| Line 59: | Line 60: | ||

# '''the "loins" or reserves''' used to exploit success or reinforce elsewhere. |

# '''the "loins" or reserves''' used to exploit success or reinforce elsewhere. |

||

The Zulu forces were generally grouped into 3 levels: regiments; corps of several regiments; and "armies" or bigger formations. With enough manpower, these could be marshaled and maneuvered in the Western equivalent of divisional strength. The Zulu king Cetawasyo, for example, two decades before the [[Anglo-Zulu War]] of 1879, cemented his rule with a victory at Ndondakusuka, using a battlefield deployment of 30,000 troops.<ref>Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 195–196</ref> An [[inDuna]] guided each regiment, and he in turn answered to senior izinduna who controlled the corps grouping. Overall guidance of the host was furnished by elder izinduna, usually with many years of experience. One or more of these elder chiefs might accompany a big force on an important mission. Coordination of tactical movements was supplied by the indunas who used hand signals and messengers. Generally before deploying for combat, the regiments were made to [[Squatting position|squat]] in a semicircle. This semi-circular squat served to align all echelons towards the coming set-piece battle, while the commanders made final assignments and adjustments. While formidable in action, the Zulu arrangements for a pitched set-piece struggle could be predictable, as they usually used the same 3-part layout in their operations.<ref>Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, Ian Knight, Osprey: 2002, pp. 5–58</ref> |

The Zulu forces were generally grouped into 3 levels: regiments; corps of several regiments; and "armies" or bigger formations. With enough manpower, these could be marshaled and maneuvered in the Western equivalent of divisional strength. The Zulu king Cetawasyo, for example, two decades before the [[Anglo-Zulu War]] of 1879, cemented his rule with a victory at Ndondakusuka, using a battlefield deployment of 30,000 troops.<ref>Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 195–196</ref> An [[inDuna]] guided each regiment, and he in turn answered to senior izinduna who controlled the corps grouping. Overall guidance of the host was furnished by elder izinduna, usually with many years of experience. One or more of these elder chiefs might accompany a big force on an important mission. Coordination of tactical movements was supplied by the indunas who used hand signals and messengers. Generally before deploying for combat, the regiments were made to [[Squatting position|squat]] in a semicircle. This semi-circular squat served to align all echelons towards the coming set-piece battle, while the commanders made final assignments and adjustments. While formidable in action, the Zulu arrangements for a pitched set-piece struggle could be predictable, as they usually used the same 3-part layout in their operations.<ref name=":12">Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, Ian Knight, Osprey: 2002, pp. 5–58</ref>{{stack|[[Image:zuluorderofbattlebig.jpg|thumb|300px|Zulu order of battle.]]}}At Isandlwana, the Zulu set-piece first lured the British into splitting their strength by diversionary actions around Magogo Hills and Mangeni Falls,<ref>John Laband. 2014. Zulu Warriors: The Battle for the South African Frontier, 229.</ref> and then moved to take advantage of this British error in a careful approach march, using dispersed units that hid the full strength of the army. As one historian notes: |

||

| ⚫ | ::"Meanwhile, the joint Zulu commanders, who had indeed been considering a flank march to Chelmsford's east to join with Matshana and cut the British column off from Natal, decided instead to take advantage of the general's division of forces. They detached men to reinforce Matshana, but on the same evening of 21 January and during the next they transferred the main army across the British front to the deep shelter of the Ngwebeni valley. This was truly a masterful manoeuvre. The ''amabutho'' moved rapidly in small units, mainly concealed from the Isandlwana camp nine miles away by the Nyoni Heights. The British mounted patrols that sighted some of the apparently isolated Zulu units had no inkling an entire army was on the move."<ref>Laband. 2014. Zulu Warriors: The Battle for the South African Frontier, 229.</ref> |

||

At Isandlwana, the Zulu set-piece first lured the British into splitting their strength by diversionary actions around Magogo Hills and Mangeni Falls,<ref>John Laband. 2014. Zulu Warriors: The Battle for the South African Frontier, 229.</ref> and then moved to take advantage of this British error in a careful approach march, using dispersed units that hid the full strength of the army. As one historian notes: |

|||

| ⚫ | :: |

||

The total Zulu host was then concentrated in a deep ravine near the enemy position, pre-positioned for their classic "buffalo horns" set-piece attack, but in accordance with tradition, waiting until the omens were good for an assault. Discovered by a British cavalry patrol, the entire ''impi'' sprang up as one man, and launched their attack from some 4 miles away. The advance was met by withering British rifle, rocket and artillery fire that made part of the advance falter. The British however had divided their forces- fooled in part by preliminary Zulu feints- and other errors, such as failure to base the camp on a strong central wagon or laager fortification for example<ref>Ian Knight, Adrian Greaves (2006) The Who's who of the Anglo-Zulu War: The British</ref> also contributed to fatal weaknesses in the British defences. When pressure by the maneuvering Zulu formations caused the crumbling of the redcoat line, the Zulu prongs surged through and around the gaps, annihilating the camp's defenders.<ref>Morris, p. 545-596">Morris, pp. 545–596</ref> The liquidation of almost 1,000 European troops with modern arms by the African spearmen sparked disbelief and uproar in Britain. Aside from the losses of British regulars, and the supporting native levies, the Zulu ''impi'' killed more British officers at Isandlwana than Napoleon killed at Waterloo.<ref> Bruce Vandervort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914,p. 20-78</ref> |

The total Zulu host was then concentrated in a deep ravine near the enemy position, pre-positioned for their classic "buffalo horns" set-piece attack, but in accordance with tradition, waiting until the omens were good for an assault. Discovered by a British cavalry patrol, the entire ''impi'' sprang up as one man, and launched their attack from some 4 miles away. The advance was met by withering British rifle, rocket and artillery fire that made part of the advance falter. The British however had divided their forces- fooled in part by preliminary Zulu feints- and other errors, such as failure to base the camp on a strong central wagon or laager fortification for example<ref>Ian Knight, Adrian Greaves (2006) The Who's who of the Anglo-Zulu War: The British</ref> also contributed to fatal weaknesses in the British defences. When pressure by the maneuvering Zulu formations caused the crumbling of the redcoat line, the Zulu prongs surged through and around the gaps, annihilating the camp's defenders.<ref>Morris, p. 545-596">Morris, pp. 545–596</ref> The liquidation of almost 1,000 European troops with modern arms by the African spearmen sparked disbelief and uproar in Britain. Aside from the losses of British regulars, and the supporting native levies, the Zulu ''impi'' killed more British officers at Isandlwana than Napoleon killed at Waterloo.<ref> Bruce Vandervort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914,p. 20-78</ref> |

||

==World Wars== |

==World Wars== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

===Battle of El Alamein=== |

|||

{{expand section|date=November 2020}} |

|||

{{main|Battle of El Alamein}} |

|||

===Battle of Caen=== |

===Battle of Caen=== |

||

{{main|Battle of Caen}} |

{{main|Battle of Caen}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

When the Allies landed at Normandy, the strategy used by the commander of the British land forces, general [[Bernard Montgomery]], was to confront the feared German panzers with constantly attacking British armies on the eastern flank of the beachhead. The role of the British forces would be to act as a great shield for the Allied landing, constantly sucking the German armour on to that shield on the left (east), and constantly grinding it down with punishing blows from artillery, tanks and Allied aircraft.<ref>Nigel Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769</ref> As the shield held the Germans fast, this would open the way for the Americans to wield a great stroke in the west, on the right of the Allied line, breaking through the German defenses, where the Americans led by such commanders as Bradley and Patton, could run free. The British role in the set-piece would thus not be a glamorous one, but a brutal battle in a punishing cauldron of attrition, in and around the key city of Caen.<ref>Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769</ref> |

When the Allies landed at Normandy, the strategy used by the commander of the British land forces, general [[Bernard Montgomery]], was to confront the feared German panzers with constantly attacking British armies on the eastern flank of the beachhead. The role of the British forces would be to act as a great shield for the Allied landing, constantly sucking the German armour on to that shield on the left (east), and constantly grinding it down with punishing blows from artillery, tanks and Allied aircraft.<ref>Nigel Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769</ref> As the shield held the Germans fast, this would open the way for the Americans to wield a great stroke in the west, on the right of the Allied line, breaking through the German defenses, where the Americans led by such commanders as Bradley and Patton, could run free. The British role in the set-piece would thus not be a glamorous one, but a brutal battle in a punishing cauldron of attrition, in and around the key city of Caen.<ref>Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:50, 26 May 2021

A pitched battle or set piece battle is a battle in which both sides agree upon the fighting location and time. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter.[1][2] A pitched battle is not a chance encounter such as a skirmish, or where one side is forced to fight at a time not of their choosing such as happens in a siege or an ambush. Pitched battles continued to evolve throughout history as armies implemented new technology and tactics.

During the Prehistorical period, pitched battles were established as the primary method for organised conflict and placed an emphasis on the implementation of rudimentary hand and missile weapons in loose formations. This developed into the Classical period as weapons and armour became more sophisticated and increased the efficacy of heavy infantry. Pitched battles decreased in size and frequency during the Middle Ages and saw the implementation of heavy mounted cavalry and new counter cavalry formations. The early Modern period saw the introduction of rudimentary firearms and artillery developing new tactics to respond to the rapidly changing state of gunpowder warfare. The late Modern period saw improvements to firearms technology which saw the standardisation of rifle infantry, cavalry and artillery during battles. Pitched Battles ceased during the First world War due to technological developments establishing trench warfare and few examples remain from the Second World War. During the post war period, pitched battles effectively ceased to exist due to the evolution of squad tactics and guerrilla warfare.

Pitched battles are usually carefully planned, to maximize one's strengths against an opponent's weaknesses, and use a full range of deceptions, feints, and other manoeuvres. They are also planned to take advantage of terrain favourable to one's force. Forces strong in cavalry for example tend to favour ground favourable to cavalry, and will not select difficult swamp, forest, or mountain for the planned struggle. For example, Carthaginian general Hannibal selected relatively flat ground near the village of Cannae for his great confrontation with the Romans, not the rocky terrain of the high Apennines.[3] Likewise, Zulu commander Shaka avoided forested areas or swamps, in favour of rolling grassland (flat or on mountain slopes), where the encircling horns of the Zulu Impi could manoeuvre to effect.[4]

Prehistorical period

Pitched battles were first recorded during the prehistorical period as massed organised conflict became the primary method for the expansion of territory for early states. During the Neolithic period, from 10,000 BCE to 3000 BCE, violence was experienced endemically rather than in concentrated large-scale events.[5] Later during the prehistorical period, after 3000 BCE, battles became increasingly organised and were typified by the implementation of bronze weaponry and rudimentary missile weapons.[6]

Tollense Valley Battlefield

One of the earliest battles in Europe occurred in the Tollense Valley where a pitched battle was fought during the 13th century BCE, consisting of at least several hundred combatants.[7] Evidence of bronze weaponry and flint and bronze arrow heads indicates that archers were used alongside infantry during the battle.[8] A possible reason for the battle was the attempted crossing of a river by a large group of armed men who were confronted at a ford.[9] Archers may have been positioned at either side of the river in the attempt to cause casualties before a series of close quarter engagements.[10] The battle at Tollense Valley demonstrates that early pitched battles in the European prehistorical period were characterised by large semi-organised groups of combatants and the implementation of simple hand and missile weapons such as bows.[11]

Battle of Kadesh

Elsewhere, pitched battles had grown in frequency and size due to developments in technology and logistics during the later prehistorical period.[8] Technological improvements included the addition of Iron weaponry, shields, and cavalry which were deployed in organised formations.[7] An example of a pitched battle that demonstrated these developments was the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE between New Kingdom Egypt under Ramses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II. Evidence from reliefs at the temple of Ramesses II depict the implementation of chariots and larger infantry formations that used spears and swords for close-quarter fighting.[12] The battle itself occurred in three stages. Initially, Hittite chariots were deployed and charged an Egyptian division that was en-route to the main Egyptian camp on the North-West side of the fortress of Kadesh.[13] In the second phase of the battle, Ramesses II launched a chariot counterattack on the Hittite chariots which were plundering the Egyptian camp and pushed them back towards the Orontes River and main force of the Hittite army.[14] The third stage was a dedicated series of charges launched by both sides as the Hittite reserve was positioned and refused to retreat over the river.[15] The pitched battle resulted in an Egyptian tactical victory but a strategic stalemate for both sides.[16]

Classical period

Pitched battles continued to evolve into the Classical period as weapons technology and battlefield tactics became more complex. The widespread introduction of iron weapons increased emphasis on close quarter infantry combat as improvements in armour and larger infantry block formations made missiles less effective. [8] The Classical Greeks implemented a new and highly effective formation of spear infantry called a phalanx. By 550 BCE the Greeks had perfected the formation, which consisted of individual soldiers called hoplites forming rows of spears and shields.[17] These units would engage in pitched battles against enemies in tight formations that would press against the enemy. Only if one side faltered was the formation able to break and the pursing side engage in individual arms.[17] The success of the phalanx was demonstrated against the Persians at Marathon in 490BCE and then at Plataea in 479BCE.[18] The Macedonians under Phillip II and Alexander the Great would develop this formation further to be deeper and wield longer spears called a sarrisa. The Macedonian phalanx was extremely successful against the Persian Empire and dominated Mediterranean warfare during the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE.[18] The effective nature of these heavy infantry formations would be further developed by the Romans who established a large professional army consisting of heavily armoured infantry units and units of auxiliaries.[8]

Battle of Cannae

An example of a pitched battle that occurred during the Classical period was the battle of Cannae fought between the Roman Republic under Lucius Aemllius Paullus Gaius Tarrentius Varo and the Carthaginians under Hannibal. The pitched battle occurred on 2 August in 216 BCE near the village of Cannae in Italy. The Romans had some 80,000 infantry and 6000 cavalry, whilst Hannibal controlled around 40,000 infantry and auxiliaries and 10,000 cavalry.[19] The battle site was mutually decided as the flat river plain running along the river Aufidus and near the ancient village of Cannae.[19] The Carthaginians favoured the level ground to ensure the effective deployment of cavalry and the Romans the narrow field between the river Aufidus and the village of Cannae to make full effect of their powerful infantry.[20] Both sides carefully deployed their troops ensuring to make full advantage of their respective strategies.

The Romans had deployed their heavy infantry in a deep formation with the intention of breaking through the Carthaginian centre whilst their 6000 cavalry had been deployed on each flank positioned to defend against the superior Carthaginian cavalry.[20] Hannibal had deployed his troops with a weak centre and reinforced flanks with the intention of letting the centre break.[21] Behind his main line he positioned 8000 auxiliary infantry with the purpose of surprising the roman infantry as they pursued the faltering Carthaginian centre.[20] Hannibal was aware of the superior power of the Roman infantry and elected to out manoeuvre and trap the Romans in an encirclement. Hannibal's deployment tactic worked and although precise numbers of casualties are disputed, eight Roman legions or roughly 45,500-70,000 Roman infantry were slain. [21] The battle resulted in a decisive victory for Hannibal and illustrates the importance of heavy infantry and advanced deployment strategies for pitched battles during the period.

Middle Ages

Pitched battles during the Middle Ages decreased in overall size and frequency due to inability for states to field armies as large as those during the Classical period.[22] The potential decisiveness and possibility of the death of the leader also decreased the number of pitched battels fought.[23] Battlefield strategy also began to favour control through sieges and garrisons in fortifications such as castles.[22] However, examples of pitched battles during the period demonstrate developments in arms and armour and their effect upon tactics and deployment. Technological improvements in metalworking permitted the increased introduction of plate armour which provided superior protection in combat. Wealthy soldiers, often called knights, would combine heavy plate armour and a mount.[22] These would be deployed in devastatingly effective charges or dismounted to fight on foot dominating battlefields throughout the Middle Ages.[22] Consequently, infantry tactics during pitched battles would evolve towards the late Middle Ages to emphasise the use of polearms such as pikes and halberds. Furthermore, pitched battles during this period saw the widespread introduction of the crossbow, as evidenced at the battle of Hastings, provided a powerful alternative to bows and were effective against most forms of armour.[24]

Battle of Hastings

An important pitched battle that demonstrated the evolution of tactics and technology during the Middle Ages was the battle of Hastings fought on the 10 October 1066. This battle was fought between the Norman-French Army under William the Conqueror and the English army under Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson. This pitched battle was fought as William engaged Godwinson who deployed his army of infantry in a small dense formation at the top of a steep slope. The English formation held heavy infantry, referred to as housecarls at the centre and light infantry on the flanks.[25] Across the front of Godwinson’s battle line was a shield wall made from soldiers interlocking their shields holding spears and missile troops behind. The Normans under William deployed in three groups which consisted of their origins, Bretons on the left flank, Normans in the centre and Franco-Flemings on the right flank.[26] William deployed his missile troops which included crossbowmen, at the front of his lines with his heavy infantry and cavalry behind.[25] William’s heavily armoured Norman knights were essential in the battle as they were deployed in cavalry feints which thinned and at occasions broke Godwinson’s shield wall as they pursued fleeing Norman cavalry.[26] The repeated implementation of this battle tactic eventually led to Norman victory in the battle as they were able to draw the English into a pursuit which was then counter charged and broken.[25] The effective deployment of heavy cavalry by the Normans during this battle demonstrates the importance of technological improvements through arms and armour and evolving tactics to pitched battles during the Middle Ages.[25]

Early Modern era

Pitched battles developed significantly during the early Modern era as tactics and deployment strategies evolving rapidly with the introduction of early firearms and artillery. There was a general increase in the size of pitched battles during this period as states grew and could wield larger standing armies using improved logistics.[27] Firearms were introduced in Europe during the 16th century and revolutionised pitched battles due to their devastating effect when fired in sequence.[28] Despite this, early firearms were inaccurate and slow to fire meaning that they were most effectively deployed in smaller, mobile blocks of infantry who would fire a mass of projectiles at an enemy.[28] Due to the unreliability of these weapons these troops were supported by other groups of infantry, especially when confronted with enemy cavalry. In 16th century Italy, pike and shot infantry would have interweaving ranks of musket and pike armed soldiers to provide mobile cavalry protection. [28] Furthermore, during this period artillery would evolve from basic stone throwers to barrelled cannons capable of mobility and effective siege warfare.[29]

Battle of Nagashino

The battle of Nagashino was a pitched battle fought between the combined forces of Oda and Tokugawa clan against Takeda clan on 28 June 1575 during the Sengoku period in Japan. The battle occurred as Oda Nobunaga led 38,000 men to relieve Tokugawa forces besieged by Takeda Katsuyori at Nagashino Castle.[30] This battle represents an example of a siege that develops into a pitched battle upon the arrival of new forces. Key to Oda success during the battle was the deployment of 10,000 Ashigaru arquebusiers.[30] Firearms has been introduced to Japan by European traders as early as 1543 and had been adopted quickly.[31] Nagashino was one of the earliest examples of their effective tactical deployment.[32] Nobunaga had positioned his arquebusiers in formations to be protected from enemy cavalry by supporting Ashigaru spearmen.[32] These worked in tandem with the arquebusiers who fired organised volleys in ranks of three to repel Takeda cavalry charges and achieve victory in the battle.[30]

Late Modern era

Firearms and artillery dominated pitched battles during the late Modern era as technological improvements such as rifling improved the reliability and accuracy of the weapons. The efficacy of firearms increased dramatically during the 18th century with the introduction of rifling for enhanced range and accuracy, cartridge ammunition and magazines. As a result, most armies during this period would strictly deploy firearm infantry.[33] Notable exceptions to this would be in colonial Africa where native armies would still employ close quarter fighting to some success, such as at the battle of Isandlwana in 1879 between the Zulu Empire and the British.[34] The mobility and accuracy of artillery was also improved with rifling and sophisticated reload mechanisms and would be utilised to great effect alongside infantry throughout the 19th century.[35] Furthermore, cavalry would continue to be an effective force for pitched battles during this period as they were implemented to harass infantry formations and artillery positions. These tactics would remain in warfare until developments in technology would make pitched battles redundant by the First World War.[36]

Battle of Isandlwana

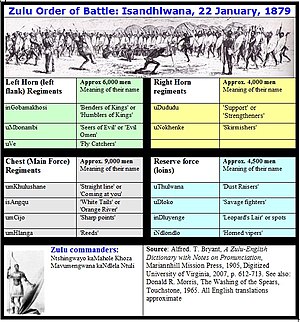

The Battle of Isandlwana was fought between the Zulu Empire and the British Empire on the 22nd of January 1879. This pitched battle saw the implementation of superior tactics to overwhelm a technologically superior force.[34] The Zulu army usually deployed in its well known "buffalo horns" formation. The attack layout was composed of three elements:[37]

- the "horns" or flanking right and left wing elements to encircle and pin the enemy. Usually these were the greener troops.

- the "chest" or central main force which delivered the coup de grace. The prime fighters made up the composition of the main force.

- the "loins" or reserves used to exploit success or reinforce elsewhere.

The Zulu forces were generally grouped into 3 levels: regiments; corps of several regiments; and "armies" or bigger formations. With enough manpower, these could be marshaled and maneuvered in the Western equivalent of divisional strength. The Zulu king Cetawasyo, for example, two decades before the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, cemented his rule with a victory at Ndondakusuka, using a battlefield deployment of 30,000 troops.[38] An inDuna guided each regiment, and he in turn answered to senior izinduna who controlled the corps grouping. Overall guidance of the host was furnished by elder izinduna, usually with many years of experience. One or more of these elder chiefs might accompany a big force on an important mission. Coordination of tactical movements was supplied by the indunas who used hand signals and messengers. Generally before deploying for combat, the regiments were made to squat in a semicircle. This semi-circular squat served to align all echelons towards the coming set-piece battle, while the commanders made final assignments and adjustments. While formidable in action, the Zulu arrangements for a pitched set-piece struggle could be predictable, as they usually used the same 3-part layout in their operations.[34]

At Isandlwana, the Zulu set-piece first lured the British into splitting their strength by diversionary actions around Magogo Hills and Mangeni Falls,[39] and then moved to take advantage of this British error in a careful approach march, using dispersed units that hid the full strength of the army. As one historian notes:

- "Meanwhile, the joint Zulu commanders, who had indeed been considering a flank march to Chelmsford's east to join with Matshana and cut the British column off from Natal, decided instead to take advantage of the general's division of forces. They detached men to reinforce Matshana, but on the same evening of 21 January and during the next they transferred the main army across the British front to the deep shelter of the Ngwebeni valley. This was truly a masterful manoeuvre. The amabutho moved rapidly in small units, mainly concealed from the Isandlwana camp nine miles away by the Nyoni Heights. The British mounted patrols that sighted some of the apparently isolated Zulu units had no inkling an entire army was on the move."[40]

The total Zulu host was then concentrated in a deep ravine near the enemy position, pre-positioned for their classic "buffalo horns" set-piece attack, but in accordance with tradition, waiting until the omens were good for an assault. Discovered by a British cavalry patrol, the entire impi sprang up as one man, and launched their attack from some 4 miles away. The advance was met by withering British rifle, rocket and artillery fire that made part of the advance falter. The British however had divided their forces- fooled in part by preliminary Zulu feints- and other errors, such as failure to base the camp on a strong central wagon or laager fortification for example[41] also contributed to fatal weaknesses in the British defences. When pressure by the maneuvering Zulu formations caused the crumbling of the redcoat line, the Zulu prongs surged through and around the gaps, annihilating the camp's defenders.[42] The liquidation of almost 1,000 European troops with modern arms by the African spearmen sparked disbelief and uproar in Britain. Aside from the losses of British regulars, and the supporting native levies, the Zulu impi killed more British officers at Isandlwana than Napoleon killed at Waterloo.[43]

World Wars

Battle of Caen

When the Allies landed at Normandy, the strategy used by the commander of the British land forces, general Bernard Montgomery, was to confront the feared German panzers with constantly attacking British armies on the eastern flank of the beachhead. The role of the British forces would be to act as a great shield for the Allied landing, constantly sucking the German armour on to that shield on the left (east), and constantly grinding it down with punishing blows from artillery, tanks and Allied aircraft.[44] As the shield held the Germans fast, this would open the way for the Americans to wield a great stroke in the west, on the right of the Allied line, breaking through the German defenses, where the Americans led by such commanders as Bradley and Patton, could run free. The British role in the set-piece would thus not be a glamorous one, but a brutal battle in a punishing cauldron of attrition, in and around the key city of Caen.[45]

The Germans had initially counterattacked the Normandy beachhead with powerful panzer and mobile forces hoping to drive to the sea by creating a wedge between the US and British armies. Failing this, they were then faced with a large, menacing British advance towards the strategic city of Caen, that threatened to collapse a great portion of their front, presenting a credible and very dangerous breakthrough threat. The British and Canadian divisions were not a secondary, defensively-oriented holding force, but aggressively sought to penetrate and destroy the German position. The Germans were thus forced to commit their strongest echelons in the theatre, the mobile panzer and SS units to avoid this peril. These were pulled deeper and deeper against the attritional anvil on the eastern flank, slowly corroding German strength and capability. The bitter confrontation tied down and weakened the Wehrmacht, thus eventually paving the way for a crushing American breakthrough in the west.[citation needed]

As General Montgomery signaled on 25 June 1944:

- "When the American attack went in west of St Lo at 1100 hours on 25 July, the main enemy armoured strength of six panzer and SS divisions was deployed on the eastern flank facing the British Army. This is a good dividend. The Americans are going well and I think things will now begin to move towards the plan outlined in M512."[46]

Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower affirmed Montgomery's overall strategy in a message of 10 July, urging stronger efforts:

- "I am familiar with your plan for generally holding firmly with your left, attracting thereto all of the enemy armour, while your right pushes down the Peninsula and threatens the rear and flank of the forces facing the Second British Army.. It appears to me that we must use all possible energy in a determined effort to prevent a stalemate or facing the necessity of fighting a major defensive battle with the slight depth we now have in the bridgehead... please be assured that I will produce everything that is humanly possible to assist you in any plan that promises to get us the elbow room we need. The air and everything else will be available."[47]

Montgomery's overall set-piece conception of the battle eventually bore fruit, but it took two months of bitter fighting, in and around the city of Caen, to come to fruition.[48]

Post war

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2020) |

See also

References

- ^ p. 649 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Blackwood's

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition 1989. battle, n. 1.b "With various qualifying attributes: … pitched battle, a battle which has been planned, and of which the ground has been chosen beforehand, by both sides ..."

- ^ Adrian Goldsworthy, 2019. Cannae: Hannibal's Greatest Victory

- ^ Donald Morris 1965. The Washing of the Spears

- ^ Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 14.

- ^ Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 6.

- ^ a b Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 8.

- ^ Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 66.

- ^ Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 67.

- ^ Fibiger, L; Lidke, G; Roymans, N (2018). Conflict Archaeology: Materialities of Collective Violence from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. p. 65.

- ^ Spalinger, A. J. (2005). War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom. Oxford: Wiley. p. 218.

- ^ Healy, M (2000). Armies of the Pharaohs. Oxford: Osprey. p. 39.

- ^ Healy, M (2000). Armies of the Pharaohs. Oxford: Osprey. p. 61.

- ^ Healy, M (2000). Armies of the Pharaohs. Oxford: Osprey. p. 62.

- ^ Bryce, T (2019). Warriors of Anatolia: A concise History of the Hittites. New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 165.

- ^ a b Lendon, J. E. Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 41.

- ^ a b Thomas, Carol G. (2007). Alexander the Great in his world. Malden, Mass.: BLACKWELL Pub. pp. 135–148. ISBN 978-0-470-77423-6. OCLC 214281331.

- ^ a b Daly, G (2004). Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War. London: Routledge. pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Daly, G (2004). Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War. London: Routledge. pp. 36–39.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Eve (2015). Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b c d Bradbury, Jim (2004). Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. London: Routledge. pp. 272–279. ISBN 978-0-203-64466-9. OCLC 475908407.

- ^ Daniell, Christopher (2003). From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta : England 1066-1215. London. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-136-35697-1. OCLC 860711898.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ France, John (2006). Medieval warfare, 1000-1300. Aldershot, England: Ashgate. ISBN 1-351-91847-8. OCLC 1036575887.

- ^ a b c d Daniell, Christopher (2003). From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta : England 1066-1215. London. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-1-136-35697-1. OCLC 860711898.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Bates, David (2016). William the Conqueror. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0-300-18383-2. OCLC 961455786.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Agoston, Gabor. "Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450-1800". Journal of World History. 25: 85 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Gonzales, Fernando (2004). Early modern military history, 1450-1815. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 25–28. ISBN 1-4039-0696-3. OCLC 54822678.

- ^ Rogers, Clifford (2004). Early modern military history, 1450-1815. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 20–21. ISBN 1-4039-0696-3. OCLC 54822678.

- ^ a b c Sadler, A. L. (2011). The maker of modern Japan : the life of Tokugawa Ieyasu. London: Routledge. pp. 100–104. ISBN 978-0-203-84508-0. OCLC 708564561.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. "Biting the Bullet: A Reassessment of the Development, Use and Impact of Early Firearms in Japan". Vulcan. 8: 26–30 – via Brill.

- ^ a b Turnbull, Stephen. "Biting the Bullet: A Reassessment of the Development, Use and Impact of Early Firearms in Japan". Vulcan. 8: 48–49 – via Brill.

- ^ Breeze, John (2017). Ballistic trauma : a practical guide. Jowan Penn-Barwell, Damian D. Keene, David J. O'Reilly, Jeyasankar Jeyanathan, Peter F. Mahoney (Fourth edition ed.). Switzerland: Cham. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-319-61364-2. OCLC 1008749437.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, Ian Knight, Osprey: 2002, pp. 5–58

- ^ Kiley, Kevin (2017). Artillery of the Napoleonic Wars. Frontline Books. pp. 546–548. ISBN 978-1-84832-954-6. OCLC 1245235071.

- ^ Whitman, James Q. (2012). The verdict of battle : the law of victory and the making of modern war. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-674-06811-7. OCLC 815276601.

- ^ Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 45–126

- ^ Donald Morris, 1962. The Washing of the Spears, pp. 195–196

- ^ John Laband. 2014. Zulu Warriors: The Battle for the South African Frontier, 229.

- ^ Laband. 2014. Zulu Warriors: The Battle for the South African Frontier, 229.

- ^ Ian Knight, Adrian Greaves (2006) The Who's who of the Anglo-Zulu War: The British

- ^ Morris, p. 545-596">Morris, pp. 545–596

- ^ Bruce Vandervort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914,p. 20-78

- ^ Nigel Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769

- ^ Hamilton, 1983. Master of the Battlefield pg 628-769

- ^ Hamilton, Master of the Battlefield, p757

- ^ Rick Atkinson. 2014. The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945 p 124

- ^ Alexander McKee's Caen: Anvil of Victory, 2012.

Bibliography

- "Policy of the Protectionists". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 71 (440): 645–68. June 1852. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

External links