Transhimalaya: Difference between revisions

Geology |

Conflict and Conservation |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Geology== |

==Geology== |

||

The Transhimalayas are geologically distinct from the other Himalayan ranges. They were probably formed by subduction of sediments from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. A consensus of different dating methods suggests that the older parts of this range formed in the upper Cretaceous (82-113 Mya), while the younger regions formed in the Eocene (40-60 Mya).<ref name = Debon_1986>{{cite journal | last = Debon | first = Francois | author-link = | title = The Four Plutonic Belts of the Transhimalaya-Himalaya: a Chemical, Mineralogical, Isotopic, and Chronological Synthesis along a Tibet-Nepal Section | journal = Journal of Petrology | volume = 27 | issue = 1 | pages = 219-250 | publisher = | location = | date = 1986 | language = | url = http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1018.511&rep=rep1&type=pdf | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = 22 June 2022}}</ref> |

The Transhimalayas are geologically distinct from the other Himalayan ranges. They were probably formed by subduction of sediments from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. A consensus of different dating methods suggests that the older parts of this range formed in the upper [[Cretaceous]] (82-113 Mya), while the younger regions formed in the [[Eocene]] (40-60 Mya).<ref name = Debon_1986>{{cite journal | last = Debon | first = Francois | author-link = | title = The Four Plutonic Belts of the Transhimalaya-Himalaya: a Chemical, Mineralogical, Isotopic, and Chronological Synthesis along a Tibet-Nepal Section | journal = Journal of Petrology | volume = 27 | issue = 1 | pages = 219-250 | publisher = | location = | date = 1986 | language = | url = http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1018.511&rep=rep1&type=pdf | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = 22 June 2022}}</ref> |

||

==Climate== |

==Climate== |

||

The Transhimalays generally have a cold, arid montane climate. For example, the [[Spiti valley|Spiti]] region of [[Himachal Pradesh]], India has an annual rainfall of about 170 mm.<ref name = Kala_2000/> |

The Transhimalays generally have a cold, arid montane climate. For example, the [[Spiti valley|Spiti]] region of [[Himachal Pradesh]], India has an annual rainfall of about 170 mm.<ref name = Kala_2000/> However, studies in [[Mustang District]], Nepal, indicate that climate change is warming the Transhimalayas at a rate of about 0.13 degrees a year.<ref name = Aryal_2013/> |

||

==Biodiversity== |

==Biodiversity== |

||

The Transhimalayas generally have low species diversity (and vegetation cover) and are classified as dry alpine steppes. However, a study in the Spiti region found 23 medicinal plants. Previous surveys in this region had found a total of over 800 species of [[vascular plants]].<ref name = Kala_2000>{{cite journal | last = Kala | first = Chandra Prakash | author-link = | title = Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya | journal = Biological Conservation | volume = 93 | issue = | pages = 371-9 | publisher = | location = | date = 2000 | language = | url = | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = }}</ref> |

The Transhimalayas generally have low species diversity (and vegetation cover) and are classified as dry alpine steppes. However, a study in the Spiti region found 23 medicinal plants. Previous surveys in this region had found a total of over 800 species of [[vascular plants]].<ref name = Kala_2000>{{cite journal | last = Kala | first = Chandra Prakash | author-link = | title = Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya | journal = Biological Conservation | volume = 93 | issue = | pages = 371-9 | publisher = | location = | date = 2000 | language = | url = | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = }}</ref> |

||

The Transhimalayas are also home to the once endangered [[snow leopard]], the [[Asiatic ibex]], [[yak]] |

The Transhimalayas are also home to the once endangered [[snow leopard]], the [[Eurasian lynx]], [[Tibetan wolf]], [[Asiatic ibex]], [[yak]] and [[bharal]].<ref name = Kala_2000/> |

||

===Conflict and |

===Conflict and Conservation=== |

||

The Tibetan wolf, snow leopard and lynx are major predators of livestock in the [[Ladakh]] region of India. Goats, sheep, yak and horses were their most common prey.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Namgail | first = Tsewang | author-link = | title = Carnivore-Caused Livestock Mortality in Trans-Himalaya | journal = Environ Manage | volume = 39 | issue = | pages = 490-496 | publisher = Springer | location = | date = 2007 | language = | url = | jstor = | issn = | doi = 10.1007/s00267-005-0178-2 | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = }}</ref> In Mustang, Nepal, rising temperatures and declining snowfall are reducing the area available for agriculture, forcing villagers to relocate and reducing grassland and forest cover. This has also led to bharal shifting to lower elevations, where they raid crops. In turn, this attracts snow leopards to human settlements, where they prey on livestock.<ref name = Aryal_2013>{{cite journal | last = Aryal | first = Achyut | author-link = | title = Impact of climate change on human-wildlife-ecosystem interactions in the Trans-Himalaya region of Nepal | journal = Theor Appl Climatol | volume = | issue = | pages = | publisher = Springer-Verlag | location = Wien | date = 2013 | language = | url = https://climatenepal.org.np/sites/default/files/doc_resources/Aryal%20et%20al%2C%202013%20Springer.pdf | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = 22 June 2022}}</ref> |

|||

On the other hand, many wild herbivores are out-competed and displaced by livestock.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Mishra | first = Charudutt | author-link = | title = Competition between domestic livestock and wild bharal <i>Pseudois nayaur</i> in the Indian Trans-Himalaya | journal = Journal of Applied Ecology | volume = 41 | issue = | pages = 344 – 354 | publisher = British Ecological Society | location = | date = 2004 | language = | url = | jstor = | issn = | doi = | id = | mr = | zbl = | jfm = | access-date = }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Mishra | first = Charudutt | author-link = | title = High-altitude survival: Conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife in the Trans-Himalaya | publisher = Wageningen University | series = | volume = | edition = | date = 2001 | location =The Netherlands | pages = | language = English, Dutch | url = https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/199100 | doi = | id = | isbn = | mr = | zbl = | jfm =}}</ref> Many parts of the Transhimalayas are now conserved. These include the [[Mount Kailash|Kangrinboqê National Forest Park]] in China, the [[Pin Valley National Park]] (675 sq. km.) and [[Kibber]] Wildlife Sanctuary (1400 sq. km.) in India and parts of the [[Annapurna Conservation Area]] (7,629 sq. km.) in Nepal.<ref name = Kala_2000/> |

|||

Many parts of the Transhimalayas are conserved. These include the [[Pin Valley National Park]] (675 km2) and [[Kibber]] Wildlife Sanctuary (1400 km2) in India.<ref name = Kala_2000/> |

|||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

Revision as of 07:25, 22 June 2022

| Transhimalaya (Gangdise – Nyenchen Tanglha range, Hedin Mountains) | |

|---|---|

Part of the Nyenchen Tanglha range in the Trans himalayas | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Nyenchen Tanglha |

| Elevation | 7,162 m (23,497 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,600 km (990 mi) |

| Geography | |

| State | Tibet |

| Range coordinates | 30°23′00″N 90°34′31″E / 30.383427°N 90.5752890°E |

| Parent range | Alpine orogeny, Tibetan Plateau (perimeter range) |

The Transhimalaya (also spelled Trans-Himalaya), or "Gangdise – Nyenchen Tanglha range" (Chinese: 冈底斯-念青唐古拉山脉; pinyin: Gāngdǐsī-Niànqīngtánggǔlā Shānmài), is a 1,600-kilometre-long (990 mi) mountain range in China, India and Nepal, extending in a west–east direction parallel to the main Himalayan range.[1][2] Located north of Yarlung Tsangpo river on the southern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, the Transhimalaya is composed of the Gangdise range to the west and the Nyenchen Tanglha range to the east.

The name Transhimalaya was introduced by the Swedish geographer Sven Hedin in early 20th century.[3] The Transhimalaya was described by the Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer in 1952 as an "ill-defined mountain area" with "no marked crest line or central alignment and no division by rivers." On more-modern maps the Kailas Range (Gangdise or Kang-to-sé Shan) in the west is shown as distinct from the Nyenchen Tanglha range in the east.[4]

Geology

The Transhimalayas are geologically distinct from the other Himalayan ranges. They were probably formed by subduction of sediments from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. A consensus of different dating methods suggests that the older parts of this range formed in the upper Cretaceous (82-113 Mya), while the younger regions formed in the Eocene (40-60 Mya).[1]

Climate

The Transhimalays generally have a cold, arid montane climate. For example, the Spiti region of Himachal Pradesh, India has an annual rainfall of about 170 mm.[2] However, studies in Mustang District, Nepal, indicate that climate change is warming the Transhimalayas at a rate of about 0.13 degrees a year.[5]

Biodiversity

The Transhimalayas generally have low species diversity (and vegetation cover) and are classified as dry alpine steppes. However, a study in the Spiti region found 23 medicinal plants. Previous surveys in this region had found a total of over 800 species of vascular plants.[2]

The Transhimalayas are also home to the once endangered snow leopard, the Eurasian lynx, Tibetan wolf, Asiatic ibex, yak and bharal.[2]

Conflict and Conservation

The Tibetan wolf, snow leopard and lynx are major predators of livestock in the Ladakh region of India. Goats, sheep, yak and horses were their most common prey.[6] In Mustang, Nepal, rising temperatures and declining snowfall are reducing the area available for agriculture, forcing villagers to relocate and reducing grassland and forest cover. This has also led to bharal shifting to lower elevations, where they raid crops. In turn, this attracts snow leopards to human settlements, where they prey on livestock.[5]

On the other hand, many wild herbivores are out-competed and displaced by livestock.[7][8] Many parts of the Transhimalayas are now conserved. These include the Kangrinboqê National Forest Park in China, the Pin Valley National Park (675 sq. km.) and Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary (1400 sq. km.) in India and parts of the Annapurna Conservation Area (7,629 sq. km.) in Nepal.[2]

Gallery

-

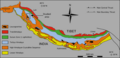

Location of Transhimalaya which includes Lhasa Terrane. In the north, Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone separates Transhimalaya from the Qiangtang terrane. In the south, Indus-Yarlung suture zone separates it from Himalayas.

-

Tectonic map of the Himalaya, modified after Le Fort & Cronin (1988). Red is Transhimalaya. Green is Indus-Yarlung suture zone, north of which lies Lhasa terrane, follow by Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone and then Qiangtang terrane.

See also

- Transhimalaya, includes the following two

References

Citations

- ^ a b Debon, Francois (1986). "The Four Plutonic Belts of the Transhimalaya-Himalaya: a Chemical, Mineralogical, Isotopic, and Chronological Synthesis along a Tibet-Nepal Section". Journal of Petrology. 27 (1): 219–250. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Kala, Chandra Prakash (2000). "Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya". Biological Conservation. 93: 371–9.

- ^ Sven Hedin's "Trans-Himalaya", Nature 82, pages 367–369 (1910)

- ^ Allen 2013, p. 142.

- ^ a b Aryal, Achyut (2013). "Impact of climate change on human-wildlife-ecosystem interactions in the Trans-Himalaya region of Nepal" (PDF). Theor Appl Climatol. Wien: Springer-Verlag. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Namgail, Tsewang (2007). "Carnivore-Caused Livestock Mortality in Trans-Himalaya". Environ Manage. 39. Springer: 490–496. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0178-2.

- ^ Mishra, Charudutt (2004). "Competition between domestic livestock and wild bharal Pseudois nayaur in the Indian Trans-Himalaya". Journal of Applied Ecology. 41. British Ecological Society: 344–354.

- ^ Mishra, Charudutt (2001). High-altitude survival: Conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife in the Trans-Himalaya (in English and Dutch). The Netherlands: Wageningen University.

Sources

- Allen, Charles (2013-01-17). A Mountain in Tibet: The Search for Mount Kailas and the Sources of the Great Rivers of Asia. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-4055-2497-1. Retrieved 2015-02-07.