Mycorrhizal network: Difference between revisions

m →Benefits for plants: I placed more emphasis on how a small amount of carbon can increase the probability of colonization. It's from this source: Philip, L. J. (2006). The role of ectomycorrhizal fungi in carbon transfer within common mycorrhizal networks (T). University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0075066 |

Thumperward (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Underground hyphal networks that connect individual plants together}} |

{{short description|Underground hyphal networks that connect individual plants together}} |

||

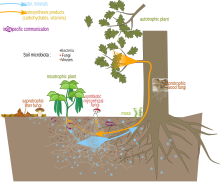

[[File:Mycorrhizal network.svg|thumb|Nutrient exchanges and communication between a mycorrhizal fungus and plants.]] '''Mycorrhizal |

[[File:Mycorrhizal network.svg|thumb|Nutrient exchanges and communication between a mycorrhizal fungus and plants.]] |

||

A '''Mycorrhizal network''' (also known as a '''common mycorrhizal network''' or '''CMN''') is an underground [[hypha]]l network created by [[mycorrhizal]] [[fungi]] that connects individual plants together and transfer water, carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients and minerals. |

|||

The formation of these networks is context-dependent, and can be influenced by factors such as [[soil fertility]], resource availability, host or myco-symbiont genotype, disturbance and seasonal variation.<ref name=Simard2012>{{Cite journal |first=S.W. |last=Simard |year=2012 |title=Mycorrhizal networks: Mechanisms, ecology and modeling |journal=Fungal Biology Reviews |volume=26 |pages=39–60 |doi=10.1016/j.fbr.2012.01.001 }}</ref> |

The formation of these networks is context-dependent, and can be influenced by factors such as [[soil fertility]], resource availability, host or myco-symbiont genotype, disturbance and seasonal variation.<ref name=Simard2012>{{Cite journal |first=S.W. |last=Simard |year=2012 |title=Mycorrhizal networks: Mechanisms, ecology and modeling |journal=Fungal Biology Reviews |volume=26 |pages=39–60 |doi=10.1016/j.fbr.2012.01.001 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 6: | Line 8: | ||

By analogy to the many roles intermediated by the [[World Wide Web]] in human communities, the many roles that mycorrhizal networks appear to play in woodland have earned them a colloquial nickname: ''the Wood Wide Web''.<ref name=Giovannettietal2006>{{Cite journal |doi=10.4161/psb.1.1.2277|pmid=19521468|title=At the Root of the Wood Wide Web|journal=Plant Signaling & Behavior|volume=1|pages=1–5|year=2006|last1=Giovannetti|first1=Manuela|last2=Avio|first2=Luciano|last3=Fortuna|first3=Paola|last4=Pellegrino|first4=Elisa|last5=Sbrana|first5=Cristiana|last6=Strani|first6=Patrizia|issue=1|pmc=2633692}}</ref><ref name=Macfarlane2016>{{cite news |last=Macfarlane |first=Robert |date=August 7, 2016 |title=The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web |url=https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-secrets-of-the-wood-wide-web |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |location=USA |access-date=November 21, 2018}}</ref> |

By analogy to the many roles intermediated by the [[World Wide Web]] in human communities, the many roles that mycorrhizal networks appear to play in woodland have earned them a colloquial nickname: ''the Wood Wide Web''.<ref name=Giovannettietal2006>{{Cite journal |doi=10.4161/psb.1.1.2277|pmid=19521468|title=At the Root of the Wood Wide Web|journal=Plant Signaling & Behavior|volume=1|pages=1–5|year=2006|last1=Giovannetti|first1=Manuela|last2=Avio|first2=Luciano|last3=Fortuna|first3=Paola|last4=Pellegrino|first4=Elisa|last5=Sbrana|first5=Cristiana|last6=Strani|first6=Patrizia|issue=1|pmc=2633692}}</ref><ref name=Macfarlane2016>{{cite news |last=Macfarlane |first=Robert |date=August 7, 2016 |title=The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web |url=https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-secrets-of-the-wood-wide-web |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |location=USA |access-date=November 21, 2018}}</ref> |

||

The importance of mycorrhizal networks [[Ecological facilitation|facilitation]] is no surprise. Mycorrhizal networks help regulate plant survival, growth, and defense. Understanding the network structure, function and performance levels are essential when studying plant ecosystems. Increasing knowledge on seed establishment, carbon transfer and the effects of climate change will drive new methods for conservation management practices for ecosystems. |

|||

==Substances transferred== |

|||

Several studies have demonstrated that mycorrhizal networks can transport carbon,<ref name=Selosse2006>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.003|pmid=16843567|title=Mycorrhizal networks: Des liaisons dangereuses?|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution |volume=21|issue=11|pages=621–628|year=2006|last1=Selosse|first1=Marc-André|last2=Richard|first2=Franck|last3=He|first3=Xinhua|last4=Simard|first4=Suzanne W.}}</ref><ref name=Teste2009>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s00442-011-2198-3|pmid=22108855|bibcode=2012Oecol.169..307H|title=Measuring carbon gains from fungal networks in understory plants from the tribe Pyroleae (Ericaceae): A field manipulation and stable isotope approach|journal=Oecologia|volume=169|issue=2|pages=307–17|last1=Hynson|first1=Nicole A.|last2=Mambelli|first2=Stefania|last3=Amend|first3=Anthony S.|last4=Dawson|first4=Todd E.|year=2012|s2cid=15300251}}</ref> [[Phosphorus cycle|phosphorus]],<ref name=Eason1991>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/BF00011205|title=Specificity of interplant cycling of phosphorus: The role of mycorrhizas|journal=Plant and Soil|volume=137|issue=2|pages=267–274|year=1991|last1=Eason|first1=W. R.|last2=Newman|first2=E. I.|last3=Chuba|first3=P. N.|s2cid=24873154}}</ref> nitrogen,<ref name=He2004>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01137.x|title=Reciprocal N (15NH4+ or 15NO3-) transfer between nonN2-fixing Eucalyptus maculata and N2-fixing Casuarina cunninghamiana linked by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus sp|journal=New Phytologist|volume=163|issue=3|pages=629–640|year=2004|last1=He|first1=Xinhua|last2=Critchley|first2=Christa|last3=Ng|first3=Hock|last4=Bledsoe|first4=Caroline|pmid=33873747}}</ref><ref name=He2009>{{cite journal|doi=10.1093/jpe/rtp015|title=Use of 15N stable isotope to quantify nitrogen transfer between mycorrhizal plants|journal=Journal of Plant Ecology|volume=2|issue=3|pages=107–118|year=2009|last1=He|first1=X.|last2=Xu|first2=M.|last3=Qiu|first3=G. Y.|last4=Zhou|first4=J.|doi-access=free}}</ref> water,<ref name="Simard2012"/><ref name=Binghman2011>{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/ece3.24|pmid=22393502|pmc=3287316|title=Do mycorrhizal network benefits to survival and growth of interior Douglas-fir seedlings increase with soil moisture stress?|journal=Ecology and Evolution|volume=1|issue=3|pages=306–316|year=2011|last1=Bingham|first1=Marcus A.|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne W.}}</ref> defense compounds,<ref name=Song2010>{{cite journal|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0013324|pmid=20967206|pmc=2954164|bibcode=2010PLoSO...513324S|title=Interplant Communication of Tomato Plants through Underground Common Mycorrhizal Networks|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=5|issue=10|pages=e13324|last1=Song|first1=Yuan Yuan|last2=Zeng|first2=Ren Sen|last3=Xu|first3=Jian Feng|last4=Li|first4=Jun|last5=Shen|first5=Xiang|last6=Yihdego|first6=Woldemariam Gebrehiwot|year=2010|doi-access=free}}</ref> and [[allelochemical]]s <ref name=Barto2011>{{cite journal|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0027195|pmid=22110615|pmc=3215695|bibcode=2011PLoSO...627195B|title=The Fungal Fast Lane: Common Mycorrhizal Networks Extend Bioactive Zones of Allelochemicals in Soils|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=6|issue=11|pages=e27195|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Hilker|first2=Monika|last3=Müller|first3=Frank|last4=Mohney|first4=Brian K.|last5=Weidenhamer|first5=Jeffrey D.|last6=Rillig|first6=Matthias C.|year=2011|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Barto2012>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.007|pmid=22818769|title=Fungal superhighways: Do common mycorrhizal networks enhance below ground communication?|journal=Trends in Plant Science|volume=17|issue=11|pages=633–637|year=2012|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Weidenhamer|first2=Jeffrey D.|last3=Cipollini|first3=Don|last4=Rillig|first4=Matthias C.}}</ref> from plant to plant. The flux of nutrients and water through hyphal networks has been proposed to be driven by a [[Source–sink dynamics|source–sink model]],<ref name=Simard2012/> where plants growing under conditions of relatively high resource availability (e.g., high-light or high-nitrogen environments) transfer carbon or nutrients to plants located in less favorable conditions. A common example is the transfer of carbon from plants with leaves located in high-light conditions in the forest canopy, to plants located in the shaded understory where light availability limits photosynthesis. |

Several studies have demonstrated that mycorrhizal networks can transport carbon,<ref name=Selosse2006>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.003|pmid=16843567|title=Mycorrhizal networks: Des liaisons dangereuses?|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution |volume=21|issue=11|pages=621–628|year=2006|last1=Selosse|first1=Marc-André|last2=Richard|first2=Franck|last3=He|first3=Xinhua|last4=Simard|first4=Suzanne W.}}</ref><ref name=Teste2009>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s00442-011-2198-3|pmid=22108855|bibcode=2012Oecol.169..307H|title=Measuring carbon gains from fungal networks in understory plants from the tribe Pyroleae (Ericaceae): A field manipulation and stable isotope approach|journal=Oecologia|volume=169|issue=2|pages=307–17|last1=Hynson|first1=Nicole A.|last2=Mambelli|first2=Stefania|last3=Amend|first3=Anthony S.|last4=Dawson|first4=Todd E.|year=2012|s2cid=15300251}}</ref> [[Phosphorus cycle|phosphorus]],<ref name=Eason1991>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/BF00011205|title=Specificity of interplant cycling of phosphorus: The role of mycorrhizas|journal=Plant and Soil|volume=137|issue=2|pages=267–274|year=1991|last1=Eason|first1=W. R.|last2=Newman|first2=E. I.|last3=Chuba|first3=P. N.|s2cid=24873154}}</ref> nitrogen,<ref name=He2004>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01137.x|title=Reciprocal N (15NH4+ or 15NO3-) transfer between nonN2-fixing Eucalyptus maculata and N2-fixing Casuarina cunninghamiana linked by the ectomycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus sp|journal=New Phytologist|volume=163|issue=3|pages=629–640|year=2004|last1=He|first1=Xinhua|last2=Critchley|first2=Christa|last3=Ng|first3=Hock|last4=Bledsoe|first4=Caroline|pmid=33873747}}</ref><ref name=He2009>{{cite journal|doi=10.1093/jpe/rtp015|title=Use of 15N stable isotope to quantify nitrogen transfer between mycorrhizal plants|journal=Journal of Plant Ecology|volume=2|issue=3|pages=107–118|year=2009|last1=He|first1=X.|last2=Xu|first2=M.|last3=Qiu|first3=G. Y.|last4=Zhou|first4=J.|doi-access=free}}</ref> water,<ref name="Simard2012"/><ref name=Binghman2011>{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/ece3.24|pmid=22393502|pmc=3287316|title=Do mycorrhizal network benefits to survival and growth of interior Douglas-fir seedlings increase with soil moisture stress?|journal=Ecology and Evolution|volume=1|issue=3|pages=306–316|year=2011|last1=Bingham|first1=Marcus A.|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne W.}}</ref> defense compounds,<ref name=Song2010>{{cite journal|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0013324|pmid=20967206|pmc=2954164|bibcode=2010PLoSO...513324S|title=Interplant Communication of Tomato Plants through Underground Common Mycorrhizal Networks|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=5|issue=10|pages=e13324|last1=Song|first1=Yuan Yuan|last2=Zeng|first2=Ren Sen|last3=Xu|first3=Jian Feng|last4=Li|first4=Jun|last5=Shen|first5=Xiang|last6=Yihdego|first6=Woldemariam Gebrehiwot|year=2010|doi-access=free}}</ref> and [[allelochemical]]s <ref name=Barto2011>{{cite journal|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0027195|pmid=22110615|pmc=3215695|bibcode=2011PLoSO...627195B|title=The Fungal Fast Lane: Common Mycorrhizal Networks Extend Bioactive Zones of Allelochemicals in Soils|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=6|issue=11|pages=e27195|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Hilker|first2=Monika|last3=Müller|first3=Frank|last4=Mohney|first4=Brian K.|last5=Weidenhamer|first5=Jeffrey D.|last6=Rillig|first6=Matthias C.|year=2011|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Barto2012>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.007|pmid=22818769|title=Fungal superhighways: Do common mycorrhizal networks enhance below ground communication?|journal=Trends in Plant Science|volume=17|issue=11|pages=633–637|year=2012|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Weidenhamer|first2=Jeffrey D.|last3=Cipollini|first3=Don|last4=Rillig|first4=Matthias C.}}</ref> from plant to plant. The flux of nutrients and water through hyphal networks has been proposed to be driven by a [[Source–sink dynamics|source–sink model]],<ref name=Simard2012/> where plants growing under conditions of relatively high resource availability (e.g., high-light or high-nitrogen environments) transfer carbon or nutrients to plants located in less favorable conditions. A common example is the transfer of carbon from plants with leaves located in high-light conditions in the forest canopy, to plants located in the shaded understory where light availability limits photosynthesis. |

||

==Types== |

== Types == |

||

There are two main types of mycorrhizal networks: [[arbuscular mycorrhizae|arbuscular mycorrhizal]] networks and [[ectomycorrhizae|ectomycorrhizal]] networks. |

There are two main types of mycorrhizal networks: [[arbuscular mycorrhizae|arbuscular mycorrhizal]] networks and [[ectomycorrhizae|ectomycorrhizal]] networks. |

||

| Line 16: | Line 19: | ||

* Ectomycorrhizal networks are formed between plants that associate with ectomycorrhizal fungi and proliferate by way of [[ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium]]. In contrast to glomeromycetes, ectomycorrhizal fungal are a highly diverse and polyphyletic group consisting of 10,000 fungal species.<ref name=Taylor2005>{{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0269-915X(05)00303-4|title=The ectomycorrhizal symbiosis: Life in the real world|journal=Mycologist|volume=19|issue=3|pages=102–112|year=2005|last1=Taylor|first1=Andy F.S.|last2=Alexander|first2=IAN}}</ref> These associations tend to be more specific, and predominate in temperate and boreal forests.<ref name=Finlay2008/> |

* Ectomycorrhizal networks are formed between plants that associate with ectomycorrhizal fungi and proliferate by way of [[ectomycorrhizal extramatrical mycelium]]. In contrast to glomeromycetes, ectomycorrhizal fungal are a highly diverse and polyphyletic group consisting of 10,000 fungal species.<ref name=Taylor2005>{{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0269-915X(05)00303-4|title=The ectomycorrhizal symbiosis: Life in the real world|journal=Mycologist|volume=19|issue=3|pages=102–112|year=2005|last1=Taylor|first1=Andy F.S.|last2=Alexander|first2=IAN}}</ref> These associations tend to be more specific, and predominate in temperate and boreal forests.<ref name=Finlay2008/> |

||

== |

== Mycoheterotrophic and mixotrophic plants == |

||

Several positive effects of mycorrhizal networks on plants have been reported.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Sheldrake|first=Merlin|title=Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures|publisher=Bodley Head|year=2020|isbn=978-1847925206|pages=172}}</ref> These include increased establishment success, higher growth rate and survivorship of seedlings;<ref name=McGuire2007>{{cite journal | last1 = McGuire | first1 = K. L. | year = 2007 | title = Common ectomycorrhizal networks may maintain [[monodominance]] in a tropical rain forest | journal = Ecology | volume = 88 | issue = 3| pages = 567–574 | doi = 10.1890/05-1173 | pmid = 17503583 | hdl = 2027.42/117206 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> improved inoculum availability for mycorrhizal infection;<ref name=Dickie2005>{{cite journal | last1 = Dickie | first1 = I.A. | last2 = Reich | first2 = P.B. | year = 2005 | title = Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities at forest edges | journal = Journal of Ecology | volume = 93 | issue = 2 | pages = 244–255 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.00977.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> transfer of water, carbon, nitrogen and other limiting resources increasing the probability for colonization in less favorable conditions.<ref name=vanderHeijden2009>{{cite journal | last1 = van der Heijden | first1 = M.G.A | last2 = Horton | first2 = T.R. | year = 2009 | title = Socialism in soil? The importance of mycorrhizal fungal networks for facilitation in natural ecosystems | journal = Journal of Ecology | volume = 97 | issue = 6 | pages = 1139–1150 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01570.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> In fact, a <1% increase in carbon has been shown to create up to 4x increase in new seedlings. These benefits have also been identified as the primary drivers of positive interactions and feedbacks between plants and mycorrhizal fungi that influence plant species abundance.<ref name=Bever2010>{{cite journal | last1 = Bever | first1 = J.D. | last2 = Dickie | first2 = I.A. | last3 = Facelli | first3 = E. | last4 = Facelli | first4 = J.M. | last5 = Klironomos | first5 = J. | last6 = Moora | first6 = M. | last7 = Rillig | first7 = M.C. | last8 = Stock | first8 = W.D. | last9 = Tibbett | first9 = M. | last10 = Zobel | first10 = M. | year = 2010 | title = Rooting Theories of Plant Community Ecology in Microbial Interactions | journal = Trends Ecol Evol | volume = 25 | issue = 8| pages = 468–478 | doi = 10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.004 | pmc = 2921684 | pmid = 20557974 }}</ref> |

|||

==Mycoheterotrophic and mixotrophic plants== |

|||

[[File:Monotropastrum humile.jpg|thumb|''[[Monotropastrum humile]]''—an example of a [[Myco-heterotrophy|myco-heterotrophic]] plant that gains all of its energy through mycorrhizal networks]] |

[[File:Monotropastrum humile.jpg|thumb|''[[Monotropastrum humile]]''—an example of a [[Myco-heterotrophy|myco-heterotrophic]] plant that gains all of its energy through mycorrhizal networks]] |

||

[[Myco-heterotrophy|Myco-heterotrophic]] plants are plants that are unable to photosynthesize and instead rely on carbon transfer from mycorrhizal networks as their main source of energy.<ref name=":0" /> This group of plants includes about 400 species. Some families that include mycotrophic species are: Ericaceae, Orchidaceae and Gentianaceae. In addition, [[mixotroph]]ic plants also benefit from energy transfer via hyphal networks. These plants have fully developed leaves but usually live in very nutrient and light limited environments that restrict their ability to photosynthesize.<ref name=Selosse2009>Selosse, M.A., Roy, M. 2009. Green plants that feed on fungi: facts and questions about mixotrophy. Trends Plant Sci. 14: 64-70.</ref> |

|||

[[Myco-heterotrophy|Myco-heterotrophic]] plants are plants that are unable to photosynthesize and instead rely on carbon transfer from mycorrhizal networks as their main source of energy.<ref name="Sheldrake" /> This group of plants includes about 400 species. Some families that include mycotrophic species are: Ericaceae, Orchidaceae and Gentianaceae. In addition, [[mixotroph]]ic plants also benefit from energy transfer via hyphal networks. These plants have fully developed leaves but usually live in very nutrient and light limited environments that restrict their ability to photosynthesize.<ref name=Selosse2009>Selosse, M.A., Roy, M. 2009. Green plants that feed on fungi: facts and questions about mixotrophy. Trends Plant Sci. 14: 64-70.</ref> |

|||

==Importance at the forest community level== |

|||

{{short description|Connections through mycorrhizal networks that facilitate communication between plants}} |

|||

Connection to mycorrhizal networks creates [[positive feedback]]s between adult trees and seedlings of the same species and can disproportionally increase the abundance of a single species, potentially resulting in [[monodominance]].<ref name=Teste2009/><ref name=McGuire2007/> Monodominance occurs when a single tree species accounts for the majority of individuals in a forest stand.<ref name=Peh2011>Peh, K.S.H.; Lewis, S.L. and Lloyd, J. 2011. Mechanisms of monodominance in diverse tropical tree-dominated systems. Journal of Ecology: 891–898.</ref> McGuire (2007), working with the monodominant tree ''[[Dicymbe corymbosa]]'' in Guyana demonstrated that seedlings with access to mycorrhizal networks had higher survival, number of leaves, and height than seedlings isolated from the ectomycorrhizal networks.<ref name=McGuire2007/> |

|||

[[Plant communication|Plants]] and fungi communicate via [[mycorrhiza]]l networks with other [[plant]]s or [[fungi]] of the same or different species. Mycorrhizal networks allow for the transfers of signals and cues between plants which influence the behavior of the connected plants by inducing [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]] or [[physiological]] changes. The chemical substances which act as these signals and cues are referred to as infochemicals. These can be [[allelochemicals]], defensive chemicals or [[nutrient]]s. Allelochemicals are used by plants to interfere with the growth or development of other plants or organisms, defensive chemicals can help plants in mycorrhizal networks defend themselves against attack by pathogens or herbivores, and transferred nutrients can affect growth and nutrition. Results of studies which demonstrate these modes of communication have led the authors to hypothesize mechanisms by which the transfer of these nutrients can affect the [[Fitness (biology)|fitness]] of the connected plants. |

|||

== Mycorrhizal networks == |

|||

===Introduction=== |

|||

{{main|Mycorrhizal networks}} |

|||

Plants and fungi form [[Mutualism (biology)|mutualistic]] [[Symbiosis|symbiotic]] relationships called [[mycorrhiza]]e, which take several forms, such as [[arbuscular mycorrhiza]]e (AM) and [[ectomycorrhiza]]e (ECM), and are widespread in nature.<ref name="Gorzelak">{{Cite journal|last1=Gorzelak|first1=Monika A.|last2=Asay|first2=Amanda K.|last3=Pickles|first3=Brian J.|last4=Simard|first4=Suzanne W.|date=2015|title=Inter-plant communication through mycorrhizal networks mediates complex adaptive behaviour in plant communities|journal=AoB Plants|volume=7|pages=plv050|doi=10.1093/aobpla/plv050|pmid=25979966|pmc=4497361|issn=2041-2851}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last1=Song|first1=Yuan Yuan|last2=Zeng|first2=Ren Sen|last3=Xu|first3=Jian Feng|last4=Li|first4=Jun|last5=Shen|first5=Xiang|last6=Yihdego|first6=Woldemariam Gebrehiwot|date=2010-10-13|title=Interplant Communication of Tomato Plants through Underground Common Mycorrhizal Networks|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=5|issue=10|pages=e13324|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0013324|pmid=20967206|pmc=2954164|issn=1932-6203|bibcode=2010PLoSO...513324S|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Hilker|first2=Monika|last3=Müller|first3=Frank|last4=Mohney|first4=Brian K.|last5=Weidenhamer|first5=Jeffrey D.|last6=Rillig|first6=Matthias C.|date=2011-11-14|title=The Fungal Fast Lane: Common Mycorrhizal Networks Extend Bioactive Zones of Allelochemicals in Soils|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=6|issue=11|pages=e27195|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0027195|pmid=22110615|pmc=3215695|issn=1932-6203|bibcode=2011PLoSO...627195B|doi-access=free}}</ref> Host plants provide [[Photosynthesis|photosynthetically]] derived [[carbohydrate]]s to the mycorrhizal fungi, which use them in [[metabolism]], either for energy or to increase the size of their [[hypha]]l networks; and the fungal partner provides benefits to the plant in the form of improved uptake of soil derived nutrients, [[drought tolerance|drought resistance]], and increased resistance to soil and [[foliar]] pathogens and other organisms.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last1=ZHANG|first1=Yi-Can|last2=LIU|first2=Chun-Yan|last3=WU|first3=Qiang-Sheng|date=2017-05-12|title=Mycorrhiza and Common Mycorrhizal Network Regulate the Production of Signal Substances in Trifoliate Orange (Poncirus trifoliata)|journal=Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca|volume=45|issue=1|pages=43|doi=10.15835/nbha45110731|issn=1842-4309|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last1=Babikova|first1=Zdenka|last2=Gilbert|first2=Lucy|last3=Bruce|first3=Toby J. A.|last4=Birkett|first4=Michael|last5=Caulfield|first5=John C.|last6=Woodcock|first6=Christine|last7=Pickett|first7=John A.|last8=Johnson|first8=David|date=2013-05-09|title=Underground signals carried through common mycelial networks warn neighbouring plants of aphid attack|journal=Ecology Letters|volume=16|issue=7|pages=835–843|doi=10.1111/ele.12115|pmid=23656527|issn=1461-023X}}</ref> |

|||

The importance of mycorrhizal networks [[Ecological facilitation|facilitation]] is no surprise. Mycorrhizal networks help regulate plant survival, growth, and defense. Understanding the network structure, function and performance levels are essential when studying plant ecosystems. Increasing knowledge on seed establishment, carbon transfer and the effects of climate change will drive new methods for conservation management practices for ecosystems. |

|||

The physical unit created by interconnected networks of mycorrhizal fungal [[hypha]]e connecting plants of the same or different [[species]] is termed a common mycorrhizal network (CMN), or simply a [[mycorrhizal network]], and it provides benefits to both partners.<ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Beiler|first2=Kevin J.|last3=Bingham|first3=Marcus A.|last4=Deslippe|first4=Julie R.|last5=Philip|first5=Leanne J.|last6=Teste|first6=François P.|date=2012-04-01|title=Mycorrhizal networks: Mechanisms, ecology and modelling|journal=Fungal Biology Reviews|volume=26|issue=1|pages=39–60|doi=10.1016/j.fbr.2012.01.001|issn=1749-4613}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last1=Barto|first1=E. Kathryn|last2=Weidenhamer|first2=Jeffrey D.|last3=Cipollini|first3=Don|last4=Rillig|first4=Matthias C.|date=2012-11-01|title=Fungal superhighways: do common mycorrhizal networks enhance below ground communication?|journal=Trends in Plant Science|volume=17|issue=11|pages=633–637|doi=10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.007|pmid=22818769|issn=1360-1385}}</ref> Mycorrhizal networks are created by the fungal partner and can range in size from square centimeters to tens of square meters and can be initiated by either AM or ECM fungi.<ref name=":15"/> AM networks tend to be less expansive than ECM networks, but AM networks can attach many plants, because AM fungi tend to be less specific in which host they choose and, therefore, can create wider networks.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":6">{{Citation|last1=Gilbert|first1=L.|title=Plant–Plant Communication Through Common Mycorrhizal Networks|date=2017|work=Advances in Botanical Research|pages=83–97|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=9780128014318|last2=Johnson|first2=D.|doi=10.1016/bs.abr.2016.09.001}}</ref><ref name=":16">{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Perry|first2=David A.|last3=Jones|first3=Melanie D.|last4=Myrold|first4=David D.|last5=Durall|first5=Daniel M.|last6=Molina|first6=Randy|date=1997-08-07|title=Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field|journal=Nature|volume=388|issue=6642|pages=579–582|doi=10.1038/41557|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1997Natur.388..579S|doi-access=free}}</ref> In the establishment of AM networks, hyphae can either directly attach to different host plants or they can establish connections between different fungi by way of [[Anastomosis|anastomoses]].<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal|last1=Achatz|first1=Michaela|last2=Morris|first2=E. Kathryn|last3=Müller|first3=Frank|last4=Hilker|first4=Monika|last5=Rillig|first5=Matthias C.|date=2014-01-13|title=Soil hypha-mediated movement of allelochemicals: arbuscular mycorrhizae extend the bioactive zone of juglone|journal=Functional Ecology|volume=28|issue=4|pages=1020–1029|doi=10.1111/1365-2435.12208|issn=0269-8463|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

===Seedling establishment=== |

|||

== Communication == |

|||

Reports discuss the ongoing debate within the scientific community regarding what constitutes communication, but the extent of communication influences how a biologist perceives behaviors.<ref name=":19">{{Cite journal|last=SCOTT-PHILLIPS|first=T. C.|date=2008-01-18|title=Defining biological communication|journal=Journal of Evolutionary Biology|volume=21|issue=2|pages=387–395|doi=10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01497.x|pmid=18205776|issn=1010-061X|doi-access=free}}</ref> Communication is commonly defined as imparting or exchanging information. Biological communication, however, is often defined by how [[Fitness (biology)|fitness]] in an organism is affected by the transfer of information in both the sender and the receiver.<ref name=":19" /><ref name=":20">{{Cite journal|last1=Padje|first1=Anouk van’t|last2=Whiteside|first2=Matthew D|last3=Kiers|first3=E Toby|date=2016-08-01|title=Signals and cues in the evolution of plant–microbe communication|journal=Current Opinion in Plant Biology|volume=32|pages=47–52|doi=10.1016/j.pbi.2016.06.006|pmid=27348594|issn=1369-5266|hdl=1871.1/c745b0c0-7789-4fc5-8d93-3edfa94ec108|url=https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/c745b0c0-7789-4fc5-8d93-3edfa94ec108|hdl-access=free}}</ref> Signals are the result of evolved behavior in the sender and effect a change in the receiver by imparting information about the sender's environment. Cues are similar in origin but only effect the fitness of the receiver.<ref name=":20" /> Both signals and cues are important elements of communication, but workers maintain caution as to when it can be determined that transfer of information benefits both senders and receivers. Thus, the extent of biological communication can be in question without rigorous experimentation.<ref name=":20" /> It has, therefore, been suggested that the term infochemical be used for chemical substances which can travel from one organism to another and elicit changes. This is important to understanding biological communication where it is not clearly delineated that communication involves a signal that can be [[Adaptive behavior|adaptive]] to both sender and receiver.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== Behavior and information transfer === |

|||

A [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]] or [[physiological]] change in a plant due to a signal or cue from its environment constitutes behavior in plants, and plants connected by a mycorrhizal network have the ability to alter their behavior based on the signals or cues they receive from other plants.<ref name="Gorzelak" /> These signals or cues can be biochemical, electrical, or can involve nutrient transfer.<ref name="Gorzelak" /> Plants release chemicals both above- and below-ground to communicate with their neighbors to reduce damage from their environment.<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal|last1=Song|first1=Yuan Yuan|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne W.|last3=Carroll|first3=Allan|last4=Mohn|first4=William W.|last5=Zeng|first5=Ren Sen|date=2015-02-16|title=Defoliation of interior Douglas-fir elicits carbon transfer and stress signalling to ponderosa pine neighbors through ectomycorrhizal networks|journal=Scientific Reports|volume=5|issue=1|pages=8495|doi=10.1038/srep08495|pmid=25683155|pmc=4329569|issn=2045-2322|bibcode=2015NatSR...5E8495S}}</ref> Changes in plant behavior invoked by the transfer of infochemicals vary depending on [[environmental factor]]s, the types of plants involved and the type of mycorrhizal network.<ref name="Gorzelak" /><ref name=":9">{{Citation|last1=Latif|first1=S.|title=Allelopathy and the Role of Allelochemicals in Plant Defence|date=2017|work=Advances in Botanical Research|pages=19–54|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=9780128014318|last2=Chiapusio|first2=G.|last3=Weston|first3=L.A.|doi=10.1016/bs.abr.2016.12.001}}</ref> In a study of orange seedlings, mycorrhizal networks acted to transfer infochemicals, and the presence of a mycorrhizal network affected the growth of plants and enhanced production of signaling molecules.<ref name=":3" /> One argument in support of the claim mycorrhizal can transfer various infochemicals is that they have been show to transfer molecules such as [[lipid]]s, [[carbohydrate]]s and [[amino acid]]s.<ref name=":6" /> Thus, transfer of infochemicals via mycorrhizal networks can act to influence plant behavior. |

|||

There are three main types of infochemicals shown to act as response inducing signals or cues by plants in mycorrhizal networks, as evidenced by increased effects on plant behavior: allelochemicals, defensive chemicals and nutrients. |

|||

=== Allelopathic communication === |

|||

[[Allelopathy]] is the process by which plants produce [[secondary metabolite]]s known as [[allelochemicals]], which can interfere with the development of other plants or organisms.<ref name=":9" /> Allelochemicals can affect nutrient uptake, photosynthesis and growth; furthermore, they can [[Downregulation and upregulation|down regulate]] defense [[gene]]s, affect [[Mitochondrion|mitochondrial]] function, and disrupt [[membrane permeability]] leading to issues with [[Cellular respiration|respiration]].<ref name=":9" /> |

|||

Plants produce many types of allelochemicals, such as [[Thiophene|thiopenes]] and [[juglone]], which can be [[volatilized]] or [[Exudate|exuded]] by the roots into the [[rhizosphere]].<ref name=":7" /> Plants release allelochemicals due to [[Biotic stress|biotic]] and [[Abiotic stress|abiotic]] stresses in their environment and often release them in conjunction with defensive compounds.<ref name=":9" /> In order for allelochemicals to have a detrimental effect on a target plant, they must exist in high enough concentrations to be [[Toxicity|toxic]], but, much like animal [[pheromone]]s, allelochemicals are released in very small amounts and rely on the reaction of the target plant to amplify their effects.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":9" /> Due to their lower concentrations and the ease in which they are degraded in the environment, the toxicity of allelochemicals is limited by [[soil moisture]], [[soil structure]], and [[Soil organic matter|organic matter]] types and [[microbes]] present in soils.<ref name=":7" /> The effectiveness of allelopathic interactions has been called into question in native [[habitat]]s due to the effects of them passing through soils, but studies have shown that mycorrhizal networks make their transfer more efficient.<ref name=":2" /> These infochemicals are hypothesized to be able to travel faster via mycorrhizal networks, because the networks protect them from some hazards of being transmitted through the soil, such as [[Leaching (agriculture)|leaching]] and degradation.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":5" /> This increased transfer speed is hypothesized to occur if the allelochemicals move via water on hyphal surfaces or by [[cytoplasmic streaming]].<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":7" /> Studies have reported concentrations of allelochemicals two to four times higher in plants connected by mycorrhizal networks.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":5" /> Thus, mycorrhizal networks can facilitate the transfer of these infochemicals. |

|||

Studies have demonstrated [[Correlation and dependence|correlations]] between increased levels of allelochemicals in target plants and the presence of mycorrhizal networks. These studies strongly suggest that mycorrhizal networks increase the transfer of allelopathic chemicals and expand the range, called the bio-active zone, in which they can disperse and maintain their function.<ref name=":2" /> Furthermore, studies indicate increased bio-active zones aid in the effectiveness of the allelochemicals because these infochemicals cannot travel very far without a mycorrhizal network.<ref name=":5" /> There was greater accumulation of allelochemicals, such as thiopenes and the herbicide imazamox, in target plants connected to a supplier plant via a mycorrhizal network than without that connection, supporting the conclusion that the mycorrhizal network increased the bio-active zone of the allelochemical.<ref name=":2" /> Allelopathic chemicals have also been demonstrated to inhibit target plant growth when target and supplier are connected via AM networks.<ref name=":2" /> The black walnut is one of the earliest studied examples of allelopathy and produces juglone, which inhibits growth and water uptake in neighboring plants.<ref name=":7" /> In studies of juglone in black walnuts and their target species, the presence of mycorrhizal networks caused target plants to exhibit reduced growth by increasing the transfer of the infochemical.<ref name=":7" /> Spotted knapweed, an allelopathic invasive species, provides further evidence of the ability of mycorrhizal networks to contribute to the transfer of allelochemicals. Spotted knapweed can alter which plant species a certain AM fungus prefers to connect to, changing the structure of the network so that the invasive plant shares a network with its target.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Mummey|first1=Daniel L.|last2=Rillig|first2=Matthias C.|date=2006-08-30|title=The invasive plant species Centaurea maculosa alters arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in the field|journal=Plant and Soil|volume=288|issue=1–2|pages=81–90|doi=10.1007/s11104-006-9091-6|s2cid=9476741|issn=0032-079X}}</ref> These and other studies provide evidence that mycorrhizal networks can facilitate the effects on plant behavior caused by allelochemicals. |

|||

=== Defensive communication === |

|||

Mycorrhizal networks can connect many different plants and provide shared pathways by which plants can transfer infochemicals related to attacks by pathogens or herbivores, allowing receiving plants to react in the same way as the infected or infested plants.<ref name=":5" /> A variety of plant derived substances act as these infochemicals. |

|||

When plants are attacked they can manifest physical changes, such as strengthening their cell walls, depositing [[callose]], or forming cork.<ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last=Prasannath|first=K.|date=2017-11-22|title=Plant defense-related enzymes against pathogens: a review|journal=AGRIEAST: Journal of Agricultural Sciences|volume=11|issue=1|pages=38|doi=10.4038/agrieast.v11i1.33|issn=1391-5886|doi-access=free}}</ref> They can also manifest biochemical changes, including the production of [[volatile organic compound]]s (VOCs) or the [[Upregulation|up-regulation]] of genes producing other defensive enzymes, many of which are toxic to pathogens or herbivores.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11">{{Cite journal|last=Lu|first=Hua|date=2009-08-01|title=Dissection of salicylic acid-mediated defense signaling networks|journal=Plant Signaling & Behavior|volume=4|issue=8|pages=713–717|doi=10.4161/psb.4.8.9173|pmid=19820324|pmc=2801381|issn=1559-2324}}</ref><ref name=":12">{{Cite journal|last1=Turner|first1=John G.|last2=Ellis|first2=Christine|last3=Devoto|first3=Alessandra|date=2002-05-01|title=The Jasmonate Signal Pathway|journal=The Plant Cell|volume=14|issue=suppl 1|pages=S153–S164|doi=10.1105/tpc.000679|pmid=12045275|issn=1040-4651|pmc=151253}}</ref> [[Salicylic acid]] (SA) and its derivatives, like methyl salicylate, are VOCs which help plants to recognize infection or attack and to organize other plant defenses, and exposure to them in animals can cause [[pathological]] processes.<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":13">{{Cite journal|last1=Dempsey|first1=D’Maris Amick|last2=Klessig|first2=Daniel F.|date=2017-03-23|title=How does the multifaceted plant hormone salicylic acid combat disease in plants and are similar mechanisms utilized in humans?|journal=BMC Biology|volume=15|issue=1|pages=23|doi=10.1186/s12915-017-0364-8|pmid=28335774|pmc=5364617|issn=1741-7007}}</ref> [[Terpenoid]]s are produced constituently in many plants or are produced as a response to stress and act much like methyl salicylate.<ref name=":13" /> [[Jasmonate]]s are a class of VOCs produced by the [[jasmonic acid]] (JA) pathway. Jasmonates are used in plant defense against insects and pathogens and can cause the expression of [[Protease|proteases]], which defend against insect attack.<ref name=":12" /> Plants have many ways to react to attack, including the production of VOCs, which studies report can coordinate defenses among plants connected by mycorrhizal networks. |

|||

Many studies report that mycorrhizal networks facilitate the coordination of defenses between connected plants using volatile organic compounds and other plant defensive enzymes acting as infochemicals. |

|||

Priming occurs when a plant's defenses are activated before an attack. Studies have shown that priming of plant defenses among plants in mycorrhizal networks may be activated by the networks, as they make it easier for these infochemicals to propagate among the connected plants. The defenses of uninfected plants are primed by their response via the network to the terpenoids produced by the infected plants.<ref name=":14">{{Cite journal|last1=Sharma|first1=Esha|last2=Anand|first2=Garima|last3=Kapoor|first3=Rupam|date=2017-01-12|title=Terpenoids in plant and arbuscular mycorrhiza-reinforced defence against herbivorous insects|journal=Annals of Botany|volume=119|issue=5|pages=791–801|doi=10.1093/aob/mcw263|pmid=28087662|pmc=5378189|issn=0305-7364}}</ref> AM networks can prime plant defensive reactions by causing them to increase the production of terpinoids.<ref name=":14" /> |

|||

In a study of tomato plants connected via an AM mycorrhizal network, a plant not infected by a fungal pathogen showed evidence of defensive priming when another plant in the network was infected, causing the uninfected plant to up-regulate genes for the SA and JA pathways.<ref name=":1" /> Similarly, aphid-free plants were shown to only be able to express the SA pathways when a mycorrhizal network connected them to infested plants. Furthermore, only then did they display resistance to the herbivore, showing that the plants were able to transfer defensive infochemicals via the mycorrhizal network.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

Many insect herbivores are drawn to their food by VOCs. When the plant is consumed, however, the composition of the VOCs change, which can then cause them to repel the herbivores and attract insect predators, such as [[parasitoid wasp]]s.<ref name=":13" /> Methyl salicylate was shown to be the primary VOC produced by beans in a study which demonstrated this effect. It was found to be in high concentrations in infested and uninfested plants, which were only connected via a mycorrhizal network.<ref name=":4" /> A plant sharing a mycorrhizal network with another that is attacked will display similar defensive strategies, and its defenses will be primed to increase the production of toxins or chemicals which repel attackers or attract defensive species.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

In another study, introduction of budworm to Douglas fir trees led to increased production of defensive enzymes in uninfested ponderosa pines connected to the damaged tree by an ECM network. This effect demonstrates that defensive infochemicals transferred through such a network can cause rapid increases in resistance and defense in uninfested plants of a different species.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

The results of these studies support the conclusion that both ECM and AM networks provide pathways for defensive infochemicals from infected or infested hosts to induce defensive changes in uninfected or uninfested [[conspecific]] and [[heterospecific]] plants, and that some recipient species generally receive less damage from infestation or infection.<ref name="Gorzelak" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8" /> |

|||

== Nutrient transfer == |

|||

=== Overview === |

|||

Numerous studies have reported that carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus are transferred between [[conspecific]] and [[heterospecific]] plants via AM and ECM networks.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":8" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Philip|first1=Leanne|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne|last3=Jones|first3=Melanie|date=2010-09-22|title=Pathways for below-ground carbon transfer between paper birch and Douglas-fir seedlings|journal=Plant Ecology & Diversity|volume=3|issue=3|pages=221–233|doi=10.1080/17550874.2010.502564|s2cid=85188897|issn=1755-0874}}</ref><ref name=":17">{{Cite journal|last1=Selosse|first1=Marc-André|last2=Richard|first2=Franck|last3=He|first3=Xinhua|last4=Simard|first4=Suzanne W.|date=2006-11-01|title=Mycorrhizal networks: des liaisons dangereuses?|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution|volume=21|issue=11|pages=621–628|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.003|pmid=16843567|issn=0169-5347}}</ref> Other nutrients may also be transferred, as strontium and rubidium, which are calcium and potassium analogs respectively, have also been reported to move via an AM network between conspecific plants.<ref name=":18">{{Cite journal|last1=Meding|first1=S.M.|last2=Zasoski|first2=R.J.|date=2008-01-01|title=Hyphal-mediated transfer of nitrate, arsenic, cesium, rubidium, and strontium between arbuscular mycorrhizal forbs and grasses from a California oak woodland|journal=Soil Biology and Biochemistry|volume=40|issue=1|pages=126–134|doi=10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.07.019|issn=0038-0717}}</ref> Scientists believe that transfer of nutrients by way of mycorrhizal networks could act to alter the behavior of receiving plants by inducing physiological or biochemical changes, and there is evidence that these changes have improved nutrition, growth and survival of receiving plants.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

=== Mechanisms === |

|||

Several mechanisms have been observed and proposed by which nutrients can move between plants connected by a mycorrhizal network, including source-sink relationships, preferential transfer and kin related mechanisms. |

|||

Transfer of nutrients can follow a source-sink relationship where nutrients move from areas of higher concentration to areas of lower concentration.<ref name="Gorzelak" /> An experiment with grasses and [[forb]]s from a California oak woodland showed that nutrients were transferred between plant species via an AM mycorrhizal network, with different species acting as sources and sinks for different elements.<ref name=":18" /> Nitrogen has also been shown to flow from [[Nitrogen fixation|nitrogen-fixing]] plants to non-nitrogen fixing plants through a mycorrhizal network following a source-sink relationship.<ref name=":17" /> |

|||

It has been demonstrated that mechanisms exist by which mycorrhizal fungi can preferentially allocate nutrients to certain plants without a source-sink relationship.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Fellbaum|first1=Carl R.|last2=Mensah|first2=Jerry A.|last3=Cloos|first3=Adam J.|last4=Strahan|first4=Gary E.|last5=Pfeffer|first5=Philip E.|last6=Kiers|first6=E. Toby|last7=Bücking|first7=Heike|date=2014-05-02|title=Fungal nutrient allocation in common mycorrhizal networks is regulated by the carbon source strength of individual host plants|journal=New Phytologist|volume=203|issue=2|pages=646–656|doi=10.1111/nph.12827|pmid=24787049|issn=0028-646X}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kiers|first1=E. T.|last2=Duhamel|first2=M.|last3=Beesetty|first3=Y.|last4=Mensah|first4=J. A.|last5=Franken|first5=O.|last6=Verbruggen|first6=E.|last7=Fellbaum|first7=C. R.|last8=Kowalchuk|first8=G. A.|last9=Hart|first9=M. M.|date=2011-08-11|title=Reciprocal Rewards Stabilize Cooperation in the Mycorrhizal Symbiosis|journal=Science|volume=333|issue=6044|pages=880–882|doi=10.1126/science.1208473|pmid=21836016|issn=0036-8075|bibcode=2011Sci...333..880K|s2cid=44812991|url=https://semanticscholar.org/paper/634db4c306fa3a357f08dbe5276ed7ae9a4efe73}}</ref> Studies have also detailed bi-directional transfer of nutrients between plants connected by a network, and evidence indicates that carbon can be shared between plants unequally, sometimes to the benefit of one species over another.<ref name=":16" /><ref name=":17" /> |

|||

Kinship can act as another transfer mechanism. More carbon has been found to be exchanged between the roots of more closely related Douglas firs sharing a network than more distantly related roots.<ref name=":15"/> Evidence is also mounting that [[micronutrient]]s transferred via mycorrhizal networks can communicate relatedness between plants. Carbon transfer between Douglas fir seedlings led workers to hypothesize that micronutrient transfer via the network may have increased carbon transfer between related plants.<ref name=":15"/><ref name=":8" /> |

|||

These transfer mechanisms can facilitate movement of nutrients via mycorrhizal networks and result in behavioral modifications in connected plants, as indicated by morphological or physiological changes, due to the infochemicals being transmitted. One study reported a three-fold increase in photosynthesis in a paper birch transferring carbon to a Douglas fir, indicating a physiological change in the tree which produced the signal.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=SIMARD|first1=SUZANNE W.|last2=JONES|first2=MELANIE D.|last3=DURALL|first3=DANIEL M.|last4=PERRY|first4=DAVID A.|last5=MYROLD|first5=DAVID D.|last6=MOLINA|first6=RANDY|date=2008-06-28|title=Reciprocal transfer of carbon isotopes between ectomycorrhizal Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii|journal=New Phytologist|volume=137|issue=3|pages=529–542|doi=10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00834.x|pmid=33863069|issn=0028-646X}}</ref> Photosynthesis was also shown to be increased in Douglas fir seedlings by the transport of carbon, nitrogen and water from an older tree connected by a mycorrhizal network.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Teste|first1=François P.|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne W.|last3=Durall|first3=Daniel M.|last4=Guy|first4=Robert D.|last5=Berch|first5=Shannon M.|date=2010-01-25|title=Net carbon transfer betweenPseudotsuga menziesiivar.glaucaseedlings in the field is influenced by soil disturbance|journal=Journal of Ecology|volume=98|issue=2|pages=429–439|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01624.x|issn=0022-0477|doi-access=free}}</ref> Furthermore, nutrient transfer from older to younger trees on a network can dramatically increase growth rates of the younger receivers.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Teste|first1=François P.|last2=Simard|first2=Suzanne W.|last3=Durall|first3=Daniel M.|last4=Guy|first4=Robert D.|last5=Jones|first5=Melanie D.|last6=Schoonmaker|first6=Amanda L.|date=2009-10-01|title=Access to mycorrhizal networks and roots of trees: importance for seedling survival and resource transfer|journal=Ecology|volume=90|issue=10|pages=2808–2822|doi=10.1890/08-1884.1|pmid=19886489|issn=0012-9658}}</ref> Physiological changes due to environmental stress have also initiated nutrient transfer by causing the movement of carbon from the roots of the stressed plant to the roots of a conspecific plant over a mycorrhizal network.<ref name=":8" /> Thus, nutrients transferred through mychorrhizal networks act as signals and cues to change the behavior of the connected plants. |

|||

== Decoding of fungi communication == |

|||

[[File:Experimental set-up to detect "language" of fungi derived from their electrical spiking activity.jpg|thumb|Experimental set-up to detect "language" of fungi derived from their electrical spiking activity]][[File:Examples of electrical activity of fungi.jpg|thumb|Examples of electrical activity of fungi]] |

|||

A study decoded electrical communication between fungi into word-like components via spiking characteristics. |

|||

The spiking characteristics were specific to the fungi species and were often clustered into sentence-like series. The study found that size of fungal lexicon can be up to 50 words in the four investigated species while the most frequently used ones do not exceed 15–20 words. However, the [[semantics|meaning or informational content]], if there is any, remains unknown.<ref>{{cite news |title=Mushrooms communicate with each other using up to 50 'words', scientist claims |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/apr/06/fungi-electrical-impulses-human-language-study |access-date=13 May 2022 |work=The Guardian |date=5 April 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Study suggests mushrooms may talk to each other |url=https://www.cbsnews.com/dfw/news/study-suggests-mushrooms-may-talk-to-each-other/ |access-date=13 May 2022 |work=CBS News}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Field |first1=Katie |title=Do mushrooms really use language to talk to each other? A fungi expert investigates |url=https://phys.org/news/2022-04-mushrooms-language-fungi-expert.html |access-date=13 May 2022 |work=The Conversation |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Adamatzky |first1=Andrew |title=Language of fungi derived from their electrical spiking activity |journal=Royal Society Open Science |year=2022 |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=211926 |doi=10.1098/rsos.211926|pmid=35425630 |pmc=8984380 |arxiv=2112.09907 |bibcode=2022RSOS....911926A }}</ref> |

|||

== Evolutionary and adaptational perspectives == |

|||

It is hypothesized that [[Fitness (biology)|fitness]] is improved by the transfer of infochemicals through common mycorrhizal networks, as these signals and cues can induce responses which can help the receiver survive in its environment.<ref name=":8" /> Plants and fungus have [[Evolution|evolved]] [[heritable]] [[Genetics|genetic]] traits which influence their interactions with each other, and experiments, such as one which revealed the [[heritability]] of mycorrhizal colonization in cowpeas, provide evidence.<ref name="Gorzelak" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=ROSADO|first1=S. C. S.|last2=KROPP|first2=B. R.|last3=PICHÉ|first3=Y.|date=1994-01-01|title=Genetics of ectomycorrhizal symbiosis|journal=New Phytologist|volume=126|issue=1|pages=111–117|doi=10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb07544.x|issn=0028-646X}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Mercy|first1=M. A.|last2=Shivashankar|first2=G.|last3=Bagyaraj|first3=D. J.|date=1989-04-25|title=Mycorrhizal colonization in cowpea is host dependent and heritable|journal=Plant and Soil|volume=122|issue=2|pages=292–294|doi=10.1007/bf02444245|issn=0032-079X}}</ref> Furthermore, changes in behavior of one partner in a mycorrhizal network can affect others in the network; thus, the mycorrhizal network can provide [[selective pressure]] to increase the fitness of its members.<ref name="Gorzelak" /> |

|||

=== Adaptive mechanisms of mycorrhizal fungi and plants === |

|||

Although they remain to be vigorously demonstrated, workers have suggested mechanisms which might explain how transfer of infochemicals via mycorrhizal networks may influence the fitness of the connected plants and fungi. |

|||

A fungus may preferentially allocate carbon and defensive infochemicals to plants that supply it more carbon, as this would help to maximize its carbon uptake.<ref name=":8" /> This may happen in ecosystems where environmental stresses, such as climate change, cause fluctuations in the types of plants in the mycorrhizal network.<ref name=":8" /> A fungus might also benefit its own survival by taking carbon from one host with a surplus and giving it to another in need, thus it would insure the survival of more potential hosts and leave itself with more carbon sources should a particular host species suffer.<ref name="Gorzelak" /> Thus, preferential transfer could improve fungal fitness. |

|||

Plant fitness may also be increased in several ways. Relatedness may be a factor, as plants in a network are more likely to be related; therefore, [[kin selection]] might improve [[inclusive fitness]] and explain why a plant might support a fungus that helps other plants to acquire nutrients.<ref name="Gorzelak" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=File|first1=Amanda L.|last2=Klironomos|first2=John|last3=Maherali|first3=Hafiz|last4=Dudley|first4=Susan A.|date=2012-09-28|title=Plant Kin Recognition Enhances Abundance of Symbiotic Microbial Partner|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=7|issue=9|pages=e45648|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0045648|pmid=23029158|pmc=3460938|issn=1932-6203|bibcode=2012PLoSO...745648F|doi-access=free}}</ref> Receipt of defensive signals or cues from an infested plant would be adaptive, as the receiving plant would be able to prime its own defenses in advance of an attack by herbivores.<ref name=":13" /> Allelopathic chemicals transferred via CMNs could also affect which plants are selected for survival by limiting the growth of competitors through a reduction of their access to nutrients and light.<ref name=":2" /> Therefore, transfer of the different classes of infochemicals might prove adaptive for plants. |

|||

=== Seedling establishment === |

|||

[[File:Pseudotsuga menziesii 28236.JPG|alt=Mature Pseudotsuga Menziesii|293x293px|Mature [[Douglas fir]]|thumb]] |

|||

Seedling establishment research often is focused on forest level communities with similar fungal species. However mycorrhizal networks may shift intra- and interspecific interactions that may alter pre-established plants physiology. Shifting competition can alter the [[Species evenness|evenness]] and [[Dominance (ecology)|dominance]] of the plant community. Discovery of seedling establishment showed seedling preference is near existing plants of [[Conspecific|con]]-or [[heterospecific]] species and seedling amount is abundant.<ref name=":02">{{Cite book|last1=Perry|first1=D.A|last2=Bell|date=1992|chapter=Mycorrhizal fungi in mixed-species forests and tales of positive feedback, redundancy, and stability |title=The Ecology of Mixed-Species Stands of Trees|editor1=M.G.R. Cannell|editor2=D.C. Malcolm|editor3=P.A. Robertson|publisher=Blackwell|location=Oxford|pages=145–180}}</ref> Many believe the process of new seedlings becoming infected with existing mycorrhizae expedite their establishment within the community. The seedling inherit tremendous benefits from their new formed symbiotic relation with the fungi.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Perry|first2=David A.|last3=Jones|first3=Melanie D.|last4=Myrold|first4=David D.|last5=Durall|first5=Daniel M.|last6=Molina|first6=Randy|date=August 1997|title=Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field|journal=Nature|volume=388|issue=6642|pages=579–582|doi=10.1038/41557|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1997Natur.388..579S|doi-access=free}}</ref> The new influx of nutrients and water availability, help the seedling with growth but more importantly help ensure survival when in a stressed state.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Perry|first1=D. A.|last2=Margolis|first2=H.|last3=Choquette|first3=C.|last4=Molina|first4=R.|last5=Trappe|first5=J. M.|date=August 1989|title=Ectomycorrhizal mediation of competition between coniferous tree species|journal=New Phytologist|volume=112|issue=4|pages=501–511|doi=10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb00344.x|pmid=29265433|issn=0028-646X|doi-access=free}}</ref> Mycorrhizal networks aid in regeneration of seedlings when secondary succession occurs, seen in temperate and boreal forests.<ref name=":02" /> |

Seedling establishment research often is focused on forest level communities with similar fungal species. However mycorrhizal networks may shift intra- and interspecific interactions that may alter pre-established plants physiology. Shifting competition can alter the [[Species evenness|evenness]] and [[Dominance (ecology)|dominance]] of the plant community. Discovery of seedling establishment showed seedling preference is near existing plants of [[Conspecific|con]]-or [[heterospecific]] species and seedling amount is abundant.<ref name=":02">{{Cite book|last1=Perry|first1=D.A|last2=Bell|date=1992|chapter=Mycorrhizal fungi in mixed-species forests and tales of positive feedback, redundancy, and stability |title=The Ecology of Mixed-Species Stands of Trees|editor1=M.G.R. Cannell|editor2=D.C. Malcolm|editor3=P.A. Robertson|publisher=Blackwell|location=Oxford|pages=145–180}}</ref> Many believe the process of new seedlings becoming infected with existing mycorrhizae expedite their establishment within the community. The seedling inherit tremendous benefits from their new formed symbiotic relation with the fungi.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Perry|first2=David A.|last3=Jones|first3=Melanie D.|last4=Myrold|first4=David D.|last5=Durall|first5=Daniel M.|last6=Molina|first6=Randy|date=August 1997|title=Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field|journal=Nature|volume=388|issue=6642|pages=579–582|doi=10.1038/41557|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1997Natur.388..579S|doi-access=free}}</ref> The new influx of nutrients and water availability, help the seedling with growth but more importantly help ensure survival when in a stressed state.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Perry|first1=D. A.|last2=Margolis|first2=H.|last3=Choquette|first3=C.|last4=Molina|first4=R.|last5=Trappe|first5=J. M.|date=August 1989|title=Ectomycorrhizal mediation of competition between coniferous tree species|journal=New Phytologist|volume=112|issue=4|pages=501–511|doi=10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb00344.x|pmid=29265433|issn=0028-646X|doi-access=free}}</ref> Mycorrhizal networks aid in regeneration of seedlings when secondary succession occurs, seen in temperate and boreal forests.<ref name=":02" /> |

||

| Line 44: | Line 116: | ||

|'''Increased exchange rates of nutrients and water from other plants.''' |

|'''Increased exchange rates of nutrients and water from other plants.''' |

||

|} |

|} |

||

[[File:Pseudotsuga_menziesii_28236.JPG|alt=Mature Pseudotsuga Menziesii|293x293px|Mature [[Douglas fir]]|thumb]] |

|||

Several studies have focused on relationships between mycorrhizal networks and plants, specifically their performance and establishment rate. [[Douglas fir]] seedlings' growth expanded when planted with hardwood trees compared to unamended soils in the Oregon Mountains. Douglas firs had higher rates of ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity, richness, and photosynthetic rates when planted alongside root systems of mature Douglas firs and ''[[Betula papyrifera]]'' than compared to those seedlings who exhibited no or little growth when isolated from mature trees.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Perry|first2=David A.|last3=Smith|first3=Jane E.|last4=Molina|first4=Randy|date=June 1997|title=Effects of soil trenching on occurrence of ectomycorrhizas on Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in mature forests of Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii|journal=New Phytologist|volume=136|issue=2|pages=327–340|doi=10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00731.x|issn=0028-646X|doi-access=free}}</ref> The Douglas fir was the focus of another study to understand its preference for establishing in an ecosystem. Two shrub species, ''[[Arctostaphylos]]'' and ''[[Adenostoma]]'' both had the opportunity to colonize the seedlings with their ectomycorrhizae fungi. ''Arctostaphylos'' shrubs colonized Douglas fir seedlings who also had higher survival rates. The mycorrhizae joining the pair had greater net carbon transfer toward the seedling.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Horton|first1=Thomas R|last2=Bruns|first2=Thomas D|last3=Parker|first3=V Thomas|date=June 1999|title=Ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Arctostaphylos contribute to Pseudotsuga menziesii establishment|journal=Canadian Journal of Botany|volume=77|issue=1|pages=93–102|doi=10.1139/b98-208|issn=0008-4026}}</ref> The researchers were able to minimize environmental factors they encountered in order to avoid swaying readers in opposite directions. |

Several studies have focused on relationships between mycorrhizal networks and plants, specifically their performance and establishment rate. [[Douglas fir]] seedlings' growth expanded when planted with hardwood trees compared to unamended soils in the Oregon Mountains. Douglas firs had higher rates of ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity, richness, and photosynthetic rates when planted alongside root systems of mature Douglas firs and ''[[Betula papyrifera]]'' than compared to those seedlings who exhibited no or little growth when isolated from mature trees.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Simard|first1=Suzanne W.|last2=Perry|first2=David A.|last3=Smith|first3=Jane E.|last4=Molina|first4=Randy|date=June 1997|title=Effects of soil trenching on occurrence of ectomycorrhizas on Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in mature forests of Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii|journal=New Phytologist|volume=136|issue=2|pages=327–340|doi=10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00731.x|issn=0028-646X|doi-access=free}}</ref> The Douglas fir was the focus of another study to understand its preference for establishing in an ecosystem. Two shrub species, ''[[Arctostaphylos]]'' and ''[[Adenostoma]]'' both had the opportunity to colonize the seedlings with their ectomycorrhizae fungi. ''Arctostaphylos'' shrubs colonized Douglas fir seedlings who also had higher survival rates. The mycorrhizae joining the pair had greater net carbon transfer toward the seedling.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Horton|first1=Thomas R|last2=Bruns|first2=Thomas D|last3=Parker|first3=V Thomas|date=June 1999|title=Ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Arctostaphylos contribute to Pseudotsuga menziesii establishment|journal=Canadian Journal of Botany|volume=77|issue=1|pages=93–102|doi=10.1139/b98-208|issn=0008-4026}}</ref> The researchers were able to minimize environmental factors they encountered in order to avoid swaying readers in opposite directions. |

||

| Line 55: | Line 127: | ||

Studies have found that association with mature plant equates with higher survival of the plant and greater diversity and species richness of the mycorrhizal fungi. |

Studies have found that association with mature plant equates with higher survival of the plant and greater diversity and species richness of the mycorrhizal fungi. |

||

===Carbon transfer=== |

=== Carbon transfer === |

||

Carbon transfer has been demonstrated by experiments using isotopic <sup>14</sup>C and following the pathway from ectomycorrhizal conifer seedlings to another using mycorrhizal networks.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Reid|first1=C. P. P.|last2=Woods|first2=Frank W.|date=March 1969|title=Translocation of C^(14)-Labeled Compounds in Mycorrhizae and It Implications in Interplant Nutrient Cycling|journal=Ecology|volume=50|issue=2|pages=179–187|doi=10.2307/1934844|issn=0012-9658|jstor=1934844}}</ref> The experiment showed a bidirectional movement of the <sup>14</sup>C within ectomycorrhizae species. Further investigation of bidirectional movement and the net transfer was analyzed using pulse labeling technique with isotopes <sup>13</sup>C and <sup>14</sup>C in ectomycorrhizal species Douglas fir and ''Betula payrifera'' seedlings.<ref>{{Citation|last1=READ|first1=Larissa|pages=217–232|publisher=Kluwer Academic Publishers|isbn=978-1402042591|last2=LAWRENCE|first2=Deborah|doi=10.1007/1-4020-4260-4_13|title=Dryland Ecohydrology|year=2006}}</ref> Results displayed an overall net balance of carbon transfer between the two until the second year where the Douglas fir received carbon from ''B. payrifera''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=SIMARD|first1=SUZANNE W.|last2=JONES|first2=MELANIE D.|last3=DURALL|first3=DANIEL M.|last4=PERRY|first4=DAVID A.|last5=MYROLD|first5=DAVID D.|last6=MOLINA|first6=RANDY|date=November 1997|title=Reciprocal transfer of carbon isotopes between ectomycorrhizal Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii|journal=New Phytologist|volume=137|issue=3|pages=529–542|doi=10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00834.x|pmid=33863069|issn=0028-646X}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=Newman|first=E.I.|date=1988|pages=243–270|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=9780120139187|doi=10.1016/s0065-2504(08)60182-8|title=Advances in Ecological Research Volume 18|volume=18|series=Advances in Ecological Research|chapter=Mycorrhizal Links Between Plants: Their Functioning and Ecological Significance}}</ref> Detection of the isotopes was found in receiver plant shorts, expressing carbon transfer from fungus to plant tissues. |

Carbon transfer has been demonstrated by experiments using isotopic <sup>14</sup>C and following the pathway from ectomycorrhizal conifer seedlings to another using mycorrhizal networks.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Reid|first1=C. P. P.|last2=Woods|first2=Frank W.|date=March 1969|title=Translocation of C^(14)-Labeled Compounds in Mycorrhizae and It Implications in Interplant Nutrient Cycling|journal=Ecology|volume=50|issue=2|pages=179–187|doi=10.2307/1934844|issn=0012-9658|jstor=1934844}}</ref> The experiment showed a bidirectional movement of the <sup>14</sup>C within ectomycorrhizae species. Further investigation of bidirectional movement and the net transfer was analyzed using pulse labeling technique with isotopes <sup>13</sup>C and <sup>14</sup>C in ectomycorrhizal species Douglas fir and ''Betula payrifera'' seedlings.<ref>{{Citation|last1=READ|first1=Larissa|pages=217–232|publisher=Kluwer Academic Publishers|isbn=978-1402042591|last2=LAWRENCE|first2=Deborah|doi=10.1007/1-4020-4260-4_13|title=Dryland Ecohydrology|year=2006}}</ref> Results displayed an overall net balance of carbon transfer between the two until the second year where the Douglas fir received carbon from ''B. payrifera''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=SIMARD|first1=SUZANNE W.|last2=JONES|first2=MELANIE D.|last3=DURALL|first3=DANIEL M.|last4=PERRY|first4=DAVID A.|last5=MYROLD|first5=DAVID D.|last6=MOLINA|first6=RANDY|date=November 1997|title=Reciprocal transfer of carbon isotopes between ectomycorrhizal Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii|journal=New Phytologist|volume=137|issue=3|pages=529–542|doi=10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00834.x|pmid=33863069|issn=0028-646X}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last=Newman|first=E.I.|date=1988|pages=243–270|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=9780120139187|doi=10.1016/s0065-2504(08)60182-8|title=Advances in Ecological Research Volume 18|volume=18|series=Advances in Ecological Research|chapter=Mycorrhizal Links Between Plants: Their Functioning and Ecological Significance}}</ref> Detection of the isotopes was found in receiver plant shorts, expressing carbon transfer from fungus to plant tissues. |

||

| Line 61: | Line 133: | ||

When ectomycorrhizal fungi receiver end of the plant has limited sunlight availability, there was an increase in carbon transfer, indicating a source-sink gradient of carbon among plants and shade surface area regulates carbon transfer.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Francis|first1=R.|last2=Read|first2=D. J.|date=January 1984|title=Direct transfer of carbon between plants connected by vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhizal mycelium|journal=Nature|volume=307|issue=5946|pages=53–56|doi=10.1038/307053a0|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1984Natur.307...53F|s2cid=4310303}}</ref> |

When ectomycorrhizal fungi receiver end of the plant has limited sunlight availability, there was an increase in carbon transfer, indicating a source-sink gradient of carbon among plants and shade surface area regulates carbon transfer.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Francis|first1=R.|last2=Read|first2=D. J.|date=January 1984|title=Direct transfer of carbon between plants connected by vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhizal mycelium|journal=Nature|volume=307|issue=5946|pages=53–56|doi=10.1038/307053a0|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1984Natur.307...53F|s2cid=4310303}}</ref> |

||

===Water transfer=== |

=== Water transfer === |

||

Isotopic tracers and fluorescent dyes have been used to establish the water transfer between conspecific or heterospecific plants. The hydraulic lift aids in water transfer from deep-rooted trees to seedlings. Potentially indicating this could be a problem within drought-stressed plants which form these mycorrhizal networks with neighbors. The extent would depend on the severity of drought and tolerance of another plant species.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2007-07-13|title=Common mycorrhizal networks provide a potential pathway for the transfer of hydraulically lifted water between plants|journal=Journal of Experimental Botany|volume=58|issue=12|pages=3484|doi=10.1093/jxb/erm266|issn=0022-0957}}</ref> |

Isotopic tracers and fluorescent dyes have been used to establish the water transfer between conspecific or heterospecific plants. The hydraulic lift aids in water transfer from deep-rooted trees to seedlings. Potentially indicating this could be a problem within drought-stressed plants which form these mycorrhizal networks with neighbors. The extent would depend on the severity of drought and tolerance of another plant species.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2007-07-13|title=Common mycorrhizal networks provide a potential pathway for the transfer of hydraulically lifted water between plants|journal=Journal of Experimental Botany|volume=58|issue=12|pages=3484|doi=10.1093/jxb/erm266|issn=0022-0957}}</ref> |

||

== Importance == |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

Several positive effects of mycorrhizal networks on plants have been reported.<ref name="Sheldrake">{{Cite book|last=Sheldrake|first=Merlin|title=Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures|publisher=Bodley Head|year=2020|isbn=978-1847925206|pages=172}}</ref> These include increased establishment success, higher growth rate and survivorship of seedlings;<ref name=McGuire2007>{{cite journal | last1 = McGuire | first1 = K. L. | year = 2007 | title = Common ectomycorrhizal networks may maintain [[monodominance]] in a tropical rain forest | journal = Ecology | volume = 88 | issue = 3| pages = 567–574 | doi = 10.1890/05-1173 | pmid = 17503583 | hdl = 2027.42/117206 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> improved inoculum availability for mycorrhizal infection;<ref name=Dickie2005>{{cite journal | last1 = Dickie | first1 = I.A. | last2 = Reich | first2 = P.B. | year = 2005 | title = Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities at forest edges | journal = Journal of Ecology | volume = 93 | issue = 2 | pages = 244–255 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.00977.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> transfer of water, carbon, nitrogen and other limiting resources increasing the probability for colonization in less favorable conditions.<ref name=vanderHeijden2009>{{cite journal | last1 = van der Heijden | first1 = M.G.A | last2 = Horton | first2 = T.R. | year = 2009 | title = Socialism in soil? The importance of mycorrhizal fungal networks for facilitation in natural ecosystems | journal = Journal of Ecology | volume = 97 | issue = 6 | pages = 1139–1150 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01570.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> In fact, a <1% increase in carbon has been shown to create up to 4x increase in new seedlings. These benefits have also been identified as the primary drivers of positive interactions and feedbacks between plants and mycorrhizal fungi that influence plant species abundance.<ref name=Bever2010>{{cite journal | last1 = Bever | first1 = J.D. | last2 = Dickie | first2 = I.A. | last3 = Facelli | first3 = E. | last4 = Facelli | first4 = J.M. | last5 = Klironomos | first5 = J. | last6 = Moora | first6 = M. | last7 = Rillig | first7 = M.C. | last8 = Stock | first8 = W.D. | last9 = Tibbett | first9 = M. | last10 = Zobel | first10 = M. | year = 2010 | title = Rooting Theories of Plant Community Ecology in Microbial Interactions | journal = Trends Ecol Evol | volume = 25 | issue = 8| pages = 468–478 | doi = 10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.004 | pmc = 2921684 | pmid = 20557974 }}</ref> |

|||

Connection to mycorrhizal networks creates [[positive feedback]]s between adult trees and seedlings of the same species and can disproportionally increase the abundance of a single species, potentially resulting in [[monodominance]].<ref name=Teste2009/><ref name=McGuire2007/> Monodominance occurs when a single tree species accounts for the majority of individuals in a forest stand.<ref name=Peh2011>Peh, K.S.H.; Lewis, S.L. and Lloyd, J. 2011. Mechanisms of monodominance in diverse tropical tree-dominated systems. Journal of Ecology: 891–898.</ref> McGuire (2007), working with the monodominant tree ''[[Dicymbe corymbosa]]'' in Guyana demonstrated that seedlings with access to mycorrhizal networks had higher survival, number of leaves, and height than seedlings isolated from the ectomycorrhizal networks.<ref name=McGuire2007/> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Entangled Life]] |

* [[Entangled Life]] |

||

* [[Plant to plant communication via mycorrhizal networks]] |

|||

* [[Suzanne Simard]] |

* [[Suzanne Simard]] |

||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

{{refs}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

* [http://www.radiolab.org/story/from-tree-to-shining-tree/ Radiolab: ''From Tree to Shining Tree''] |

* [http://www.radiolab.org/story/from-tree-to-shining-tree/ Radiolab: ''From Tree to Shining Tree''] |

||

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWOqeyPIVRo BBC News: ''How trees secretly talk to each other''] |

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWOqeyPIVRo BBC News: ''How trees secretly talk to each other''] |

||

* [https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/nature/wood-wide-web.html NOVA: ''The Wood Wide Web''] |

* [https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/nature/wood-wide-web.html NOVA: ''The Wood Wide Web''] |

||

[[Category:Plant communication]] |

|||

[[Category:Fungus ecology]] |

[[Category:Fungus ecology]] |

||

Revision as of 15:16, 28 July 2022

A Mycorrhizal network (also known as a common mycorrhizal network or CMN) is an underground hyphal network created by mycorrhizal fungi that connects individual plants together and transfer water, carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients and minerals.

The formation of these networks is context-dependent, and can be influenced by factors such as soil fertility, resource availability, host or myco-symbiont genotype, disturbance and seasonal variation.[1]

By analogy to the many roles intermediated by the World Wide Web in human communities, the many roles that mycorrhizal networks appear to play in woodland have earned them a colloquial nickname: the Wood Wide Web.[2][3]

The importance of mycorrhizal networks facilitation is no surprise. Mycorrhizal networks help regulate plant survival, growth, and defense. Understanding the network structure, function and performance levels are essential when studying plant ecosystems. Increasing knowledge on seed establishment, carbon transfer and the effects of climate change will drive new methods for conservation management practices for ecosystems.