Giant hummingbird: Difference between revisions

rm a cite from lead |

rejig sections per WP:Birds; use common name rather than binomial in text |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''giant hummingbird''' (''Patagona gigas'') is the [[monotypic|only member]] of the genus ''Patagona'' and the largest member of the [[hummingbird]] family, weighing {{convert|18|-|24|g|abbr=on}} and having a wingspan of approximately {{convert|21.5|cm|abbr=on}} and length of {{convert|23|cm|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Lasiewski>{{cite journal|last1=Lasiewski|first1=Robert C.|last2=Weathers|first2=Wesley W.|last3=Bernstein|first3=Marvin H.|title=Physiological responses of the giant hummingbird, ''Patagona gigas'' |journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology|date= |

The '''giant hummingbird''' (''Patagona gigas'') is the [[monotypic|only member]] of the genus ''Patagona'' and the largest member of the [[hummingbird]] family, weighing {{convert|18|-|24|g|abbr=on}} and having a wingspan of approximately {{convert|21.5|cm|abbr=on}} and length of {{convert|23|cm|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Lasiewski>{{cite journal|last1=Lasiewski|first1=Robert C.|last2=Weathers|first2=Wesley W.|last3=Bernstein|first3=Marvin H.|title=Physiological responses of the giant hummingbird, ''Patagona gigas'' |journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology|date=1967 |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=797–813|doi=10.1016/0010-406X(67)90342-8 }}</ref> This is approximately the same length as a [[European starling]] or a [[northern cardinal]], though the giant hummingbird is considerably lighter because it has a slender build and long [[beak|bill]], making the body a smaller proportion of the total length. This weight is almost twice that of the next heaviest hummingbird species<ref name=fernandez>{{cite journal|last1=Fernández|first1=María José|last2=Dudley|first2=Robert|last3=Bozinovic|first3=Francisco|title=Comparative energetics of the giant hummingbird | journal=Physiological and Biochemical Zoology | date=2011 | volume=84 | issue=3 | pages=333–340 |doi=10.1086/660084 }}</ref> and ten times that of the smallest, the [[bee hummingbird]].<ref name=Healy>{{cite journal|last1=Healy|first1=Susan|last2=Hurly|first2=T. Andrew|title=Hummingbirds|journal=Current Biology|date=2006|volume=16|issue=11|pages=R392–R393|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.015 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

== Taxonomy == |

== Taxonomy == |

||

The giant hummingbird was [[species description|described]] and illustrated in 1824 by the French ornithologist [[Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot]] based on a specimen that Vieillot mistakenly believed had been collected in Brazil.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Vieillot | first=Louis Jean Pierre | author-link=Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot | year=1824 | title=La Galerie des Oiseaux | volume=1 | language=French | location=Paris | publisher=Constant Chantepie | page=296–297; Plate 180 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/58574706 }}</ref> The [[type locality (biology)|type locality]] was designated as [[Valparaíso]] in Chile by [[Carl Eduard Hellmayr]] in 1945.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Hellmayr | first=Carl Eduard | author-link=Carl Eduard Hellmayr | year=1932 | title=The Birds of Chile | series=Field Museum Natural History Publications. Zoological Series. Volume 19 | page=230 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2763821 }}</ref><ref>{{ cite book | editor-last=Peters | editor-first=James Lee | editor-link=James L. Peters | year=1945 | title=Check-List of Birds of the World | volume=5 | publisher=Harvard University Press | place=Cambridge, Massachusetts | page=95 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14480106 }}</ref> The giant hummingbird is now the only species placed in the genus ''Patagona'' that was introduced by [[George Robert Gray]] in 1840.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Gray | first=George Robert | author-link=George Robert Gray | year=1840 | title=A List of the Genera of Birds : with an Indication of the Typical Species of Each Genus | location=London | publisher=R. and J.E. Taylor | page=14 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/13668908 }}</ref><ref name=ioc>{{cite web| editor1-last=Gill | editor1-first=Frank | editor1-link=Frank Gill (ornithologist) | editor2-last=Donsker | editor2-first=David | editor3-last=Rasmussen | editor3-first=Pamela | editor3-link=Pamela Rasmussen | date=August 2022 | title=Hummingbirds | work=IOC World Bird List Version 12.2 | url=http://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/hummingbirds/ | publisher=International Ornithologists' Union | access-date=13 September 2022 }}</ref> |

The giant hummingbird was [[species description|described]] and illustrated in 1824 by the French ornithologist [[Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot]] based on a specimen that Vieillot mistakenly believed had been collected in Brazil.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Vieillot | first=Louis Jean Pierre | author-link=Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot | year=1824 | title=La Galerie des Oiseaux | volume=1 | language=French | location=Paris | publisher=Constant Chantepie | page=296–297; Plate 180 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/58574706 }}</ref> The [[type locality (biology)|type locality]] was designated as [[Valparaíso]] in Chile by [[Carl Eduard Hellmayr]] in 1945.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Hellmayr | first=Carl Eduard | author-link=Carl Eduard Hellmayr | year=1932 | title=The Birds of Chile | series=Field Museum Natural History Publications. Zoological Series. Volume 19 | page=230 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2763821 }}</ref><ref>{{ cite book | editor-last=Peters | editor-first=James Lee | editor-link=James L. Peters | year=1945 | title=Check-List of Birds of the World | volume=5 | publisher=Harvard University Press | place=Cambridge, Massachusetts | page=95 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14480106 }}</ref> The giant hummingbird is now the only species placed in the genus ''Patagona'' that was introduced by [[George Robert Gray]] in 1840.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Gray | first=George Robert | author-link=George Robert Gray | year=1840 | title=A List of the Genera of Birds : with an Indication of the Typical Species of Each Genus | location=London | publisher=R. and J.E. Taylor | page=14 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/13668908 }}</ref><ref name=ioc>{{cite web| editor1-last=Gill | editor1-first=Frank | editor1-link=Frank Gill (ornithologist) | editor2-last=Donsker | editor2-first=David | editor3-last=Rasmussen | editor3-first=Pamela | editor3-link=Pamela Rasmussen | date=August 2022 | title=Hummingbirds | work=IOC World Bird List Version 12.2 | url=http://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/hummingbirds/ | publisher=International Ornithologists' Union | access-date=13 September 2022 }}</ref> |

||

[[Molecular phylogenetic]] studies have shown that the giant hummingbird has no close relatives and is [[sister taxon|sister]] to the hummingbird subfamily [[Trochilinae]], a large clade containing the [[Tribe (biology)|tribes]] [[Lampornithini]] (mountain gems), [[Mellisugini]] (bees) and [[Trochilini]] (emeralds).<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McGuire |first=J. |last2=Witt |first2=C. |last3=Remsen |first3=J.V. |last4=Corl |first4=A. |last5=Rabosky |first5=D. |last6=Altshuler |first6=D. |last7=Dudley |first7=R. |date=2014 |title=Molecular phylogenetics and the diversification of hummingbirds |journal=Current Biology |volume=24 |issue=8 |pages=910–916 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.016 |pmid=24704078 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Belonging to the family Trochilidae (hummingbirds), ''P. gigas'' is one of approximately 331 described species in this family, making it the second largest group of new world birds. Trochilids are further divided into about 104 genera.<ref name=Mcguire07>{{cite journal|last1=McGuire|first1=J. A.|last2=Witt|first2=Christopher C.|last3=Altshuler|first3=Douglas L.|last4=Remsen Jr|first4=J. V.|title=Phylogenetic Systematics and Biogeography of Hummingbirds: Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood Analyses of Partitioned Data and Selection of an Appropriate Partitioning Strategy|journal=Systematic Biology|date=2007|volume=56|issue=5|pages=837–856|doi=10.1080/10635150701656360|pmid=17934998|doi-access=free}}</ref> It is thought that the species is comparatively old and, for the most part, a failed evolutionary experiment in enlarging hummingbird size given it has not diverged and proliferated.<ref name=Mcguire07 /> |

|||

Two [[subspecies]] are recognised:<ref name=ioc/> |

|||

Traditional morphologic taxonomic inquiries show ''P. gigas'' to be substantially different from the other taxa of hummingbirds.<ref name=Oses /> A 2008 phylogenetic review found a 97.5% likelihood that ''P. gigas'' has diverged substantially enough from the proposed the closest phylogenetic [[clade]]s to be considered belonging to a single-species clade named Patagonini.<ref name=Mcguire09>{{cite journal|last1=McGuire|first1=Jimmy A.|last2=Witt|first2=Christopher C.|last3=Remsen|first3=J. V.|last4=Dudley|first4=R.|last5=Altshuler|first5=Douglas L.|title=A higher-level taxonomy for hummingbirds|journal=Journal of Ornithology|date=5 August 2008|volume=150|issue=1|pages=155–165|doi=10.1007/s10336-008-0330-x|s2cid=1918245}}</ref> This is in accord with [[International Ornithologists' Union|International Ornithological Union]]’s taxonomic classification of ''P. gigas'' in a genus of its own.<ref name=gill>{{cite web|last1=Gill|first1=F|last2=Donsker|first2=D|title=IOC World Bird List. 5.1|url=http://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/hummingbirds/|website=WorldBirdNames.org|access-date=16 April 2015}}</ref> |

|||

* ''P. g. peruviana'' [[Adolphe Boucard|Boucard]], 1893 – southwest Colombia to north Chile and northwest Argentina |

|||

* ''P. g. gigas'' (Vieillot, 1824) – central, south Chile and west-central Argentina |

|||

These subspecies are thought to have emerged as a result of partial geographical separation of populations by volcanic activity in the Andes predating the [[Miocene]]; however, there remain areas of contact between the species, hence the lack of full speciation.<ref name=Oses /> The proposed phylogenetic system for hummingbirds suggested by McGuire ''et al.'' (2009)<ref name=Mcguire09>{{cite journal|last1=McGuire|first1=Jimmy A.|last2=Witt|first2=Christopher C.|last3=Remsen|first3=J. V.|last4=Dudley|first4=R.|last5=Altshuler|first5=Douglas L.|title=A higher-level taxonomy for hummingbirds|journal=Journal of Ornithology|date=5 August 2008|volume=150|issue=1|pages=155–165|doi=10.1007/s10336-008-0330-x|s2cid=1918245}}</ref> accommodates the possible elevation of these subspecies to species rank. |

|||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

[[File:Patagona gigas-perching.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:Patagona gigas-perching.jpg|thumb|right|In [[Cusco]], [[Peru]]]] |

||

| ⚫ | The giant hummingbird can be identified by its large size and characteristics such as the presence of an eye-ring, straight bill longer than the head, dull colouration, very long wings (approaching the tail tip when stowed), long and moderately forked tail,<ref name=Clark>{{cite journal|last1=Clark|first1=Christopher J.|title=The evolution of tail shape in hummingbirds|journal=The Auk|date=2010|volume=127|issue=1|pages=44–56|doi=10.1525/auk.2009.09073|s2cid=86540202}}</ref> tarsi feathered to the toes and large, sturdy feet. There is no difference between the sexes.<ref name=Oses>{{cite book|last1=Osés|first1=C. S.|title=Taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of the Andean hummingbird genera ''Coeligena'' Lesson, 1832; ''Pterophanes'' Gould, 1849; ''Ensifera'' Lesson 1843; and ''Patagona'' Gray, 1840 (Aves: Trochiliformes) | date=2003 | publisher=Bonn University | location=Bonn, Germany | edition=1st|url=http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/2003/0273/0273.htm|access-date=18 April 2015}}</ref><ref name=Vonwehrden>{{cite journal|last1=Von Wehrden|first1=H.|title=The giant hummingbird (''Patagona gigas'') in the mountains of central Argentina and a climatic envelope model for its distribution | journal=Wilson Journal of Ornithology | date=2008|volume=120|issue=3|pages=648–651|doi=10.1676/07-111.1}}</ref> Juveniles have small corrugations on the lateral [[Beak|beak culmen]].<ref name=Oritz>{{cite journal|last1=Oritz-Crespo|first1=F. I.|title=A new method to separate immature and adult hummingbirds |journal=The Auk|date=1972|volume=89|issue=4|pages=851–857|doi=10.2307/4084114|jstor=4084114}}</ref> |

||

In [[Bolivia]], the giant hummingbird is known in [[Quechua language|Quechua]] as ''burro q'enti'', the Spanish word ''[[burro]]'' referring to its dull [[plumage]].<ref name="jf&nk">{{cite book |title=Birds of the High Andes |last=Fjeldsa |first=Jon |author2=Krabbe, Niels |year=1990 |publisher=Zoological Museum, [[University of Copenhagen]], Denmark |page=876}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The giant hummingbird occasionally glides in flight, a behavior very rare among hummingbirds. Its elongated wings allow more efficient glides than do those of other hummingbirds.<ref name=Templin>{{cite journal|last1=Templin|first1=R.J.|title=The spectrum of animal flight: insects to pterosaurs|journal=Progress in Aerospace Sciences | date=2000 | volume=36 |issue=5–6 | pages=393–436 |doi=10.1016/S0376-0421(00)00007-5}}</ref> The giant hummingbird's voice is a distinctive loud, sharp and whistling "chip".<ref name=Ricardo>{{cite book|last1=Ricardo|first1=R.|title=Multi-ethnic Bird Guide of the Subantarctic Forests of South America|date=2010|publisher=University of North Texas Press|pages=171–173|edition=2nd}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The giant hummingbird occasionally glides in flight, a behavior very rare among hummingbirds. Its elongated wings allow more efficient glides than do those of other hummingbirds.<ref name=Templin>{{cite journal|last1=Templin|first1=R.J.|title=The spectrum of animal flight: insects to pterosaurs|journal=Progress in Aerospace Sciences|date= |

||

== Distribution and habitat == |

== Distribution and habitat == |

||

The giant hummingbird is widely distributed throughout the length of the Andes on both the east and west sides.<ref name=Oses /> |

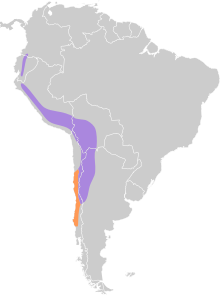

The giant hummingbird is widely distributed throughout the length of the Andes on both the east and west sides.<ref name=Oses /> It typically inhabit the higher altitude scrubland and forests that line the slopes of the Andes during the summer and then retreat to similar, lower altitude habitats in winter months.<ref name=Vonwehrden /><ref name=Herzog>{{cite journal|last1=Herzog|first1=Sebastian K.|last2=Rodrigo|first2=Soria A.|last3=Matthysen|first3=Erik|title=Seasonal variation in avian community composition in a high-Andean ''Polylepis'' (Rosaceae) forest fragment | journal=The Wilson Bulletin | date=2003 | volume=115 |issue=4|pages=438–447|doi=10.1676/03-048 |url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/210451}}</ref> The species persists through a large altitude range, with specimens retrieved from sea level up to 4600 m.<ref name=Oses /> They have shown to be fairly resilient to urbanisation and agricultural activities; however, the removal of vegetation limits their distribution in dense city areas and industrial zones.<ref name=villegas>{{cite journal|last1=Villegas|first1=Mariana|last2=Garitano-Zavala|first2=Álvaro|title=Bird community responses to different urban conditions in La Paz, Bolivia|journal=Urban Ecosystems | date=2010|volume=13|issue=3|pages=375–391|doi=10.1007/s11252-010-0126-7 }}</ref> The giant hummingbird migrates in summer to the temperate areas of South America, reaching as low as 44° S. Correspondingly, it migrates north to more tropical climates in winter (March–August), though not usually venturing higher than 28° S.<ref name=Oses /><ref name=Ricardo /> |

||

''P. g. peruviana'' occurs from Ecuador to the southeastern mountains of Peru and ''P. g. gigas'' from northern Bolivia and Chile to Argentina. Contact between subspecies is most likely to occur around the eastern slopes of the north Peruvian Andes.<ref name=Oses /> |

''P. g. peruviana'' occurs from Ecuador to the southeastern mountains of Peru and ''P. g. gigas'' from northern Bolivia and Chile to Argentina. Contact between subspecies is most likely to occur around the eastern slopes of the north Peruvian Andes.<ref name=Oses /> |

||

==Global range and population== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== Behaviour == |

== Behaviour == |

||

| ⚫ | Hummingbirds are extremely agile and acrobatic flyers, regularly partaking in sustained hovering flight, often used not only to feed on the wing but to protect their territory<ref name=SCHLUMPBERGER>{{cite journal|last1=Schlumpberger|first1=B. O.|last2=Badano|first2=E.I.|title=Diversity of floral visitors to ''Echinopsis atacamensis'' Subsp. ''Pasacana'' (Cactaceae)|journal=Haseltonia|date=2005|volume=11|pages=18–26|doi=10.2985/1070-0048(2005)11[18:DOFVTE]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> and court mates.<ref name=Healy /> The giant hummingbird is typical in that it will brazenly defend its precious energy-rich flower territory from other species and other giant hummingbirds. These birds are typically seen alone, in pairs or small family groups.<ref name=Ricardo /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Hummingbirds are extremely agile and acrobatic flyers, regularly partaking in sustained hovering flight, often used not only to feed on the wing but to protect their territory<ref name=SCHLUMPBERGER>{{cite journal|last1= |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Peru - Giant Hummingbird - Patagona gigas 01.jpg|thumb|right|Giant hummingbird in Peru]] |

[[File:Peru - Giant Hummingbird - Patagona gigas 01.jpg|thumb|right|Giant hummingbird in Peru]] |

||

The giant hummingbird hovers at an average of 15 wing beats per second, a slow rate for a hummingbird.<ref name=Lasiewski /> Its resting heart rate is 300 beats per minute, with a peak rate in flight of 1020 beats per minute.<ref name=Lasiewski /> Energy requirements for hummingbirds do not scale evenly with size increases, meaning a larger bird such as giant hummingbird requires more energy per gram to hover than a smaller bird.<ref name=hainsworth>{{cite journal | last1 = Hainsworth | first1=F.R. | last2 =Wolf | first2=L.L. | year=1972 | title=Power for hovering flight in relation to body size in hummingbirds | journal=The American Naturalist | volume=106 | issue=951 | pages=589–596 | doi=10.1086/282799 }}</ref> |

|||

The giant hummingbird requires an estimated 4.3 [[Kilocalorie|calories]] of [[food energy]] per hour to sustain its flight.<ref name=hainsworth /> This huge requirement along with the low oxygen availability and thin air (generating little lift) at the high altitudes where the giant hummingbird usually lives suggest that it is close to the viable maximum size for a hummingbird.<ref name=Altshuler>{{cite journal | last1=Altshuler | first1=D.L. | last2=Dudley | first2=R. | year=2006 | title=The physiology and biomechanics of avian flight at high altitude | journal=Integrative and Comparative Biology | volume = 46 | issue=1 | pages=62–71 | doi=10.1093/icb/icj008 | doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

== Diet == |

|||

=== Food and feeding === |

|||

[[File:Giant Hummingbirds (7426020288).jpg|thumb|Giant hummingbird]] |

[[File:Giant Hummingbirds (7426020288).jpg|thumb|Giant hummingbird]] |

||

| ⚫ | The giant hummingbird feeds mainly on nectar, visiting a range of flowers.<ref name=Ricardo /> The female giant hummingbird has been observed ingesting sources of calcium (sand, soil, slaked lime and wood ash) after the reproductive season to replenish the calcium used in egg production; the low calcium content of nectar necessitates these extra sources.<ref name=estades>{{cite journal | last1=Estades | first1 = C.F. | last2 = Vukasovic | first2 = M.A. | last3 = Tomasevic | first3 = J. A. | year = 2008 | title = Giant hummingbirds (''Patagona gigas'') ingest calcium-rich minerals | journal = Wilson Journal of Ornithology | volume = 120 | issue = 3| pages = 651–653 | doi=10.1676/07-054.1| s2cid = 86241862 }}</ref> Similarly, a nectar-based diet is low in [[protein (nutrient)|protein]] and various [[dietary mineral]]s, and this is countered by consuming insects.<ref name=estades /> |

||

| ⚫ | It regularly feeds from the flowers of the genus [[Puya (genus)|''Puya'']] in Chile, with which it enjoys a symbiotic relationship, trading pollination for food.<ref name=Ricardo /><ref name=gonzalez>{{cite journal | last1 = González-Gómez | first1 = P. L. | last2 = Valdivia | first2 = C. E. | year = 2005 | title = Direct and indirect effects of nectar robbing on the pollinating behavior of ''Patagona gigas'' (Trochilidae) | journal = Biotropica | volume = 37 | issue = 4| pages = 693–696 | doi = 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.00088.x}}</ref> As a large hovering bird, particularly at high altitudes, the giant hummingbird has extremely high metabolic requirements. It is known to feed from columnar cacti, including ''[[Oreocereus celsianus]]'' and ''[[Echinopsis atacamensis]] ssp. pasacana'', and [[List of Salvia species|''Salvia haenkei'']].<ref name=SCHLUMPBERGER /><ref name=larreaAlcazar>{{cite journal|last1=Larrea-Alcázar|first1=Daniel M.|last2=López|first2=Ramiro P.|title=Pollination biology of ''Oreocereus celsianus'' (Cactaceae), a columnar cactus inhabiting the high subtropical Andes|journal=Plant Systematics and Evolution| date=2011 |volume=295|issue=1–4|pages=129–137|doi=10.1007/s00606-011-0485-4 }}</ref><ref name=Wester>{{cite journal|last1=Wester|first1=P.|last2=Claßen-Bockhoff|first2=R.|title=Hummingbird pollination in ''Salvia haenkei'' (Lamiaceae) lacking the typical lever mechanism | journal=Plant Systematics and Evolution | date= 2006 | volume=257 | issue=3–4 | pages=133–146 | doi=10.1007/s00606-005-0366-9 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Giant hummingbird Patagonia Gigas on cactus in Peru by Devon Pike.jpeg|thumb|Giant hummingbird on cactus in Peru|alt=]] |

[[File:Giant hummingbird Patagonia Gigas on cactus in Peru by Devon Pike.jpeg|thumb|Giant hummingbird on cactus in Peru|alt=]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Considering the energy-rich nature of nectar as a food source, it attracts a large range of visitors apart from the hummingbird, which has coevolved with a plant to be the flower's most efficient pollinator.<ref name="SCHLUMPBERGER" /><ref name="gonzalez" /><ref name="larreaAlcazar" /> These other visitors, because they are not designed to access the well-hidden bounty of nectar, often damage the flowers (for example, piercing them at the base) and prevent further nectar production.<ref name="gonzalez" /> Because of its high energy requirements, the giant hummingbird alters its foraging behaviour as a direct response to nectar robbing from other birds and animals, and this reduces the viability of the hummingbird in an area with many nectar robbers, as well as indirectly affecting the plants by reducing pollination.<ref name="gonzalez" /> If alien species are introduced that become nectar thieves, it is reasonable to predict that their activities will significantly impact the local ecosystem. This could prove to be a future risk for the giant hummingbird populations because they sit close to the physical limit in their metabolic demands.<ref name="Altshuler" /> |

||

=== Breeding === |

|||

| ⚫ | Considering the energy-rich nature of nectar as a food source, it attracts a large range of visitors apart from the hummingbird, which has coevolved with a plant to be the flower's most efficient pollinator.<ref name="SCHLUMPBERGER" /><ref name="gonzalez" /><ref name="larreaAlcazar" /> These other visitors, because they are not designed to access the well-hidden bounty of nectar, often damage the flowers (for example, piercing them at the base) and prevent further nectar production.<ref name="gonzalez" /> Because of its high energy requirements, |

||

| ⚫ | There is little known of the giant hummingbird's breeding behaviour, but some generalisations can be deduced from other hummingbird species. Hummingbird males tend to have polygynous, occasionally promiscuous, behaviours<ref name=Healy /> and no involvement after copulation.<ref name=vleck>{{cite journal | last1 = Vleck | first1 = C. M. | year = 1981 | title = Hummingbird incubation: female attentiveness and egg temperature | journal = Oecologia | volume = 51 | issue = 2| pages = 199–205 | doi = 10.1007/bf00540601 }}</ref> The female builds the nest and lays a clutch of two eggs during the summer.<ref name="Fierro">{{cite journal | last1 = Fierro-Calderón | first1 = K. | last2 = Martin | first2 = T. E. | title = Reproductive biology of the violet-chested hummingbird in Venezuela and comparisons with other tropical and temperate hummingbirds | year = 2007 | url = http://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=wildbio_pubs| journal = The Condor | volume = 109 | issue = 3| pages = 680–685 | doi=10.1650/8305.1 }}</ref> A giant hummingbird nest is small considering the size of the bird, typically made near water sources and perched on a branch of a tree or shrub parallel to the ground.<ref name=Ricardo /> |

||

== |

== Cultural significance == |

||

| ⚫ | The giant hummingbird holds significant value for some of the aboriginal inhabitants of the Andes. The people of [[Chiloé Island]] believe that if a woman captures a hummingbird then they will gain great fertility from it.<ref name=Ricardo /> This is also the species that inspired the people of the [[Nazca culture]] to create the [[Nazca Lines|Nazca hummingbird geoglyph]].<ref name=Ricardo /> |

||

==Status== |

|||

| ⚫ | There is little known of |

||

| ⚫ | The range of the giant hummingbird is sizable, and its global extent of occurrence is estimated at 1,200,000 km<sup>2</sup>. Its global population is believed to be not less than 10,000 adults. The species is classified by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] as being of [[Least Concern]].<ref name="iucn status 12 November 2021" /> |

||

== Migration == |

|||

''P. gigas'' migrates in summer to the temperate areas of South America, reaching as low as 44° S. Correspondingly, it migrates north to more tropical climates in winter (March–August), though not usually venturing higher than 28° S.<ref name=Oses /><ref name=Ricardo /> |

|||

== Cultural significance == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 08:48, 14 September 2022

| Giant hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patagona gigas in Chile | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Strisores |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Patagona G.R. Gray, 1840 |

| Species: | P. gigas

|

| Binomial name | |

| Patagona gigas (Vieillot, 1824)

| |

| |

The giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas) is the only member of the genus Patagona and the largest member of the hummingbird family, weighing 18–24 g (0.63–0.85 oz) and having a wingspan of approximately 21.5 cm (8.5 in) and length of 23 cm (9.1 in).[3] This is approximately the same length as a European starling or a northern cardinal, though the giant hummingbird is considerably lighter because it has a slender build and long bill, making the body a smaller proportion of the total length. This weight is almost twice that of the next heaviest hummingbird species[4] and ten times that of the smallest, the bee hummingbird.[5]

Taxonomy

The giant hummingbird was described and illustrated in 1824 by the French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot based on a specimen that Vieillot mistakenly believed had been collected in Brazil.[6] The type locality was designated as Valparaíso in Chile by Carl Eduard Hellmayr in 1945.[7][8] The giant hummingbird is now the only species placed in the genus Patagona that was introduced by George Robert Gray in 1840.[9][10]

Molecular phylogenetic studies have shown that the giant hummingbird has no close relatives and is sister to the hummingbird subfamily Trochilinae, a large clade containing the tribes Lampornithini (mountain gems), Mellisugini (bees) and Trochilini (emeralds).[11]

Two subspecies are recognised:[10]

- P. g. peruviana Boucard, 1893 – southwest Colombia to north Chile and northwest Argentina

- P. g. gigas (Vieillot, 1824) – central, south Chile and west-central Argentina

These subspecies are thought to have emerged as a result of partial geographical separation of populations by volcanic activity in the Andes predating the Miocene; however, there remain areas of contact between the species, hence the lack of full speciation.[12] The proposed phylogenetic system for hummingbirds suggested by McGuire et al. (2009)[13] accommodates the possible elevation of these subspecies to species rank.

Description

The giant hummingbird can be identified by its large size and characteristics such as the presence of an eye-ring, straight bill longer than the head, dull colouration, very long wings (approaching the tail tip when stowed), long and moderately forked tail,[14] tarsi feathered to the toes and large, sturdy feet. There is no difference between the sexes.[12][15] Juveniles have small corrugations on the lateral beak culmen.[16]

The subspecies are visually distinguishable. P. g. peruviana is yellowish brown overall and has white on the chin and throat, where P. g. gigas is more olive green to brown and lacks white on the chin and throat.[12]

The giant hummingbird occasionally glides in flight, a behavior very rare among hummingbirds. Its elongated wings allow more efficient glides than do those of other hummingbirds.[17] The giant hummingbird's voice is a distinctive loud, sharp and whistling "chip".[18]

Distribution and habitat

The giant hummingbird is widely distributed throughout the length of the Andes on both the east and west sides.[12] It typically inhabit the higher altitude scrubland and forests that line the slopes of the Andes during the summer and then retreat to similar, lower altitude habitats in winter months.[15][19] The species persists through a large altitude range, with specimens retrieved from sea level up to 4600 m.[12] They have shown to be fairly resilient to urbanisation and agricultural activities; however, the removal of vegetation limits their distribution in dense city areas and industrial zones.[20] The giant hummingbird migrates in summer to the temperate areas of South America, reaching as low as 44° S. Correspondingly, it migrates north to more tropical climates in winter (March–August), though not usually venturing higher than 28° S.[12][18]

P. g. peruviana occurs from Ecuador to the southeastern mountains of Peru and P. g. gigas from northern Bolivia and Chile to Argentina. Contact between subspecies is most likely to occur around the eastern slopes of the north Peruvian Andes.[12]

Behaviour

Hummingbirds are extremely agile and acrobatic flyers, regularly partaking in sustained hovering flight, often used not only to feed on the wing but to protect their territory[21] and court mates.[5] The giant hummingbird is typical in that it will brazenly defend its precious energy-rich flower territory from other species and other giant hummingbirds. These birds are typically seen alone, in pairs or small family groups.[18]

Flight, anatomy and physiology

The giant hummingbird hovers at an average of 15 wing beats per second, a slow rate for a hummingbird.[3] Its resting heart rate is 300 beats per minute, with a peak rate in flight of 1020 beats per minute.[3] Energy requirements for hummingbirds do not scale evenly with size increases, meaning a larger bird such as giant hummingbird requires more energy per gram to hover than a smaller bird.[22]

The giant hummingbird requires an estimated 4.3 calories of food energy per hour to sustain its flight.[22] This huge requirement along with the low oxygen availability and thin air (generating little lift) at the high altitudes where the giant hummingbird usually lives suggest that it is close to the viable maximum size for a hummingbird.[23]

Food and feeding

The giant hummingbird feeds mainly on nectar, visiting a range of flowers.[18] The female giant hummingbird has been observed ingesting sources of calcium (sand, soil, slaked lime and wood ash) after the reproductive season to replenish the calcium used in egg production; the low calcium content of nectar necessitates these extra sources.[24] Similarly, a nectar-based diet is low in protein and various dietary minerals, and this is countered by consuming insects.[24]

It regularly feeds from the flowers of the genus Puya in Chile, with which it enjoys a symbiotic relationship, trading pollination for food.[18][25] As a large hovering bird, particularly at high altitudes, the giant hummingbird has extremely high metabolic requirements. It is known to feed from columnar cacti, including Oreocereus celsianus and Echinopsis atacamensis ssp. pasacana, and Salvia haenkei.[21][26][27]

Considering the energy-rich nature of nectar as a food source, it attracts a large range of visitors apart from the hummingbird, which has coevolved with a plant to be the flower's most efficient pollinator.[21][25][26] These other visitors, because they are not designed to access the well-hidden bounty of nectar, often damage the flowers (for example, piercing them at the base) and prevent further nectar production.[25] Because of its high energy requirements, the giant hummingbird alters its foraging behaviour as a direct response to nectar robbing from other birds and animals, and this reduces the viability of the hummingbird in an area with many nectar robbers, as well as indirectly affecting the plants by reducing pollination.[25] If alien species are introduced that become nectar thieves, it is reasonable to predict that their activities will significantly impact the local ecosystem. This could prove to be a future risk for the giant hummingbird populations because they sit close to the physical limit in their metabolic demands.[23]

Breeding

There is little known of the giant hummingbird's breeding behaviour, but some generalisations can be deduced from other hummingbird species. Hummingbird males tend to have polygynous, occasionally promiscuous, behaviours[5] and no involvement after copulation.[28] The female builds the nest and lays a clutch of two eggs during the summer.[29] A giant hummingbird nest is small considering the size of the bird, typically made near water sources and perched on a branch of a tree or shrub parallel to the ground.[18]

Cultural significance

The giant hummingbird holds significant value for some of the aboriginal inhabitants of the Andes. The people of Chiloé Island believe that if a woman captures a hummingbird then they will gain great fertility from it.[18] This is also the species that inspired the people of the Nazca culture to create the Nazca hummingbird geoglyph.[18]

Status

The range of the giant hummingbird is sizable, and its global extent of occurrence is estimated at 1,200,000 km2. Its global population is believed to be not less than 10,000 adults. The species is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being of Least Concern.[1]

References

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Patagona gigas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22687785A93168933. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22687785A93168933.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c Lasiewski, Robert C.; Weathers, Wesley W.; Bernstein, Marvin H. (1967). "Physiological responses of the giant hummingbird, Patagona gigas". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 23 (3): 797–813. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(67)90342-8.

- ^ Fernández, María José; Dudley, Robert; Bozinovic, Francisco (2011). "Comparative energetics of the giant hummingbird". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 84 (3): 333–340. doi:10.1086/660084.

- ^ a b c Healy, Susan; Hurly, T. Andrew (2006). "Hummingbirds". Current Biology. 16 (11): R392–R393. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.015.

- ^ Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1824). La Galerie des Oiseaux (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Constant Chantepie. p. 296–297; Plate 180.

- ^ Hellmayr, Carl Eduard (1932). The Birds of Chile. Field Museum Natural History Publications. Zoological Series. Volume 19. p. 230.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1945). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 5. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 95.

- ^ Gray, George Robert (1840). A List of the Genera of Birds : with an Indication of the Typical Species of Each Genus. London: R. and J.E. Taylor. p. 14.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Hummingbirds". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ McGuire, J.; Witt, C.; Remsen, J.V.; Corl, A.; Rabosky, D.; Altshuler, D.; Dudley, R. (2014). "Molecular phylogenetics and the diversification of hummingbirds". Current Biology. 24 (8): 910–916. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.016. PMID 24704078.

- ^ a b c d e f g Osés, C. S. (2003). Taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of the Andean hummingbird genera Coeligena Lesson, 1832; Pterophanes Gould, 1849; Ensifera Lesson 1843; and Patagona Gray, 1840 (Aves: Trochiliformes) (1st ed.). Bonn, Germany: Bonn University. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ McGuire, Jimmy A.; Witt, Christopher C.; Remsen, J. V.; Dudley, R.; Altshuler, Douglas L. (5 August 2008). "A higher-level taxonomy for hummingbirds". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1007/s10336-008-0330-x. S2CID 1918245.

- ^ Clark, Christopher J. (2010). "The evolution of tail shape in hummingbirds". The Auk. 127 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09073. S2CID 86540202.

- ^ a b Von Wehrden, H. (2008). "The giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas) in the mountains of central Argentina and a climatic envelope model for its distribution". Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120 (3): 648–651. doi:10.1676/07-111.1.

- ^ Oritz-Crespo, F. I. (1972). "A new method to separate immature and adult hummingbirds". The Auk. 89 (4): 851–857. doi:10.2307/4084114. JSTOR 4084114.

- ^ Templin, R.J. (2000). "The spectrum of animal flight: insects to pterosaurs". Progress in Aerospace Sciences. 36 (5–6): 393–436. doi:10.1016/S0376-0421(00)00007-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ricardo, R. (2010). Multi-ethnic Bird Guide of the Subantarctic Forests of South America (2nd ed.). University of North Texas Press. pp. 171–173.

- ^ Herzog, Sebastian K.; Rodrigo, Soria A.; Matthysen, Erik (2003). "Seasonal variation in avian community composition in a high-Andean Polylepis (Rosaceae) forest fragment". The Wilson Bulletin. 115 (4): 438–447. doi:10.1676/03-048.

- ^ Villegas, Mariana; Garitano-Zavala, Álvaro (2010). "Bird community responses to different urban conditions in La Paz, Bolivia". Urban Ecosystems. 13 (3): 375–391. doi:10.1007/s11252-010-0126-7.

- ^ a b c Schlumpberger, B. O.; Badano, E.I. (2005). "Diversity of floral visitors to Echinopsis atacamensis Subsp. Pasacana (Cactaceae)". Haseltonia. 11: 18–26. doi:10.2985/1070-0048(2005)11[18:DOFVTE]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Hainsworth, F.R.; Wolf, L.L. (1972). "Power for hovering flight in relation to body size in hummingbirds". The American Naturalist. 106 (951): 589–596. doi:10.1086/282799.

- ^ a b Altshuler, D.L.; Dudley, R. (2006). "The physiology and biomechanics of avian flight at high altitude". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (1): 62–71. doi:10.1093/icb/icj008.

- ^ a b Estades, C.F.; Vukasovic, M.A.; Tomasevic, J. A. (2008). "Giant hummingbirds (Patagona gigas) ingest calcium-rich minerals". Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 120 (3): 651–653. doi:10.1676/07-054.1. S2CID 86241862.

- ^ a b c d González-Gómez, P. L.; Valdivia, C. E. (2005). "Direct and indirect effects of nectar robbing on the pollinating behavior of Patagona gigas (Trochilidae)". Biotropica. 37 (4): 693–696. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.00088.x.

- ^ a b Larrea-Alcázar, Daniel M.; López, Ramiro P. (2011). "Pollination biology of Oreocereus celsianus (Cactaceae), a columnar cactus inhabiting the high subtropical Andes". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 295 (1–4): 129–137. doi:10.1007/s00606-011-0485-4.

- ^ Wester, P.; Claßen-Bockhoff, R. (2006). "Hummingbird pollination in Salvia haenkei (Lamiaceae) lacking the typical lever mechanism". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 257 (3–4): 133–146. doi:10.1007/s00606-005-0366-9.

- ^ Vleck, C. M. (1981). "Hummingbird incubation: female attentiveness and egg temperature". Oecologia. 51 (2): 199–205. doi:10.1007/bf00540601.

- ^ Fierro-Calderón, K.; Martin, T. E. (2007). "Reproductive biology of the violet-chested hummingbird in Venezuela and comparisons with other tropical and temperate hummingbirds". The Condor. 109 (3): 680–685. doi:10.1650/8305.1.