Alzheimer's disease in the Hispanic/Latino population: Difference between revisions

Added tags to the page using Page Curation (essay-like) |

Ira Leviton (talk | contribs) m Fixed PMC parameters in citations. Category:CS1 maint: PMC format |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{essay-like|date=December 2022}} |

{{essay-like|date=December 2022}} |

||

[[Alzheimer's disease]] (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the presence of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Goedert |first=Michel |last2=Spillantini |first2=Maria Grazia |date=2006-11-03 |title=A Century of Alzheimer's Disease |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1132814 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=314 |issue=5800 |pages=777–781 |doi=10.1126/science.1132814 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref> It is one of the most common causes of dementia, leading to memory loss, cognitive deficits, and behavioral issues.<ref name=":0" /> Currently, 5.4 million Americans have been diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease, and this number is projected to reach 15-22 million by 2050.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Reitz |first=Christiane |last2=Rogaeva |first2=Ekaterina |last3=Beecham |first3=Gary W. |date=2020-10-06 |title=Late-onset vs nonmendelian early-onset Alzheimer disease |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7673282/ |journal=Neurology: Genetics |volume=6 |issue=5 |pages=e512 |doi=10.1212/NXG.0000000000000512 |issn=2376-7839 |pmc=7673282 |pmid=33225065}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last=Vega |first=Irving E. |last2=Cabrera |first2=Laura Y. |last3=Wygant |first3=Cassandra M. |last4=Velez-Ortiz |first4=Daniel |last5=Counts |first5=Scott E. |date=2017-06-23 |editor-last=Abisambra |editor-first=Jose |title=Alzheimer’s Disease in the Latino Community: Intersection of Genetics and Social Determinants of Health |url=https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-161261 |journal=Journal of Alzheimer's Disease |volume=58 |issue=4 |pages=979–992 |doi=10.3233/JAD-161261 |pmc= |

[[Alzheimer's disease]] (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the presence of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Goedert |first=Michel |last2=Spillantini |first2=Maria Grazia |date=2006-11-03 |title=A Century of Alzheimer's Disease |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1132814 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=314 |issue=5800 |pages=777–781 |doi=10.1126/science.1132814 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref> It is one of the most common causes of dementia, leading to memory loss, cognitive deficits, and behavioral issues.<ref name=":0" /> Currently, 5.4 million Americans have been diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease, and this number is projected to reach 15-22 million by 2050.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Reitz |first=Christiane |last2=Rogaeva |first2=Ekaterina |last3=Beecham |first3=Gary W. |date=2020-10-06 |title=Late-onset vs nonmendelian early-onset Alzheimer disease |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7673282/ |journal=Neurology: Genetics |volume=6 |issue=5 |pages=e512 |doi=10.1212/NXG.0000000000000512 |issn=2376-7839 |pmc=7673282 |pmid=33225065}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last=Vega |first=Irving E. |last2=Cabrera |first2=Laura Y. |last3=Wygant |first3=Cassandra M. |last4=Velez-Ortiz |first4=Daniel |last5=Counts |first5=Scott E. |date=2017-06-23 |editor-last=Abisambra |editor-first=Jose |title=Alzheimer’s Disease in the Latino Community: Intersection of Genetics and Social Determinants of Health |url=https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-161261 |journal=Journal of Alzheimer's Disease |volume=58 |issue=4 |pages=979–992 |doi=10.3233/JAD-161261 |pmc=5874398 |pmid=28527211}}</ref> Hispanics and Latinos account for 55 million of the current population and this population is projected to rise to 97 million, accounting for 25% of the U.S. population, in 2050.<ref name=":9" /> Moreover, in 2012 379,000 Hispanic/Latinos were diagnosed with Alzheimer's, and by 2060 this number is projected to increase to 3.5 million by 2060.<ref name=":9" /> |

||

There is a large genetic component to Alzheimer's disease, with mutations in the [[Amyloid-beta precursor protein|amyloid precursor protein (APP)]], [[Apolipoprotein E|apolipoprotein E (APOE)]], [[PSEN1|presenilin 1 (PSEN1)]], [[PSEN2|presenilin-2]] (PSEN-2), [[BIN1|bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1]]), [[TREM2]], [[SORL1]], and [[Clusterin|Clusterin (CLU)]] genes increasing one's risk to develop the condition.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Breijyeh |first=Zeinab |last2=Karaman |first2=Rafik |date=2020-12-08 |title=Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7764106/ |journal=Molecules |volume=25 |issue=24 |pages=5789 |doi=10.3390/molecules25245789 |issn=1420-3049 |pmc=7764106 |pmid=33302541}}</ref><ref name=":20">{{Cite journal |last=Tosto |first=Giuseppe |last2=Reitz |first2=Christiane |date=2016-12-01 |title=Genomics of Alzheimer's disease: Value of high-throughput genomic technologies to dissect its etiology |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890850816300743 |journal=Molecular and Cellular Probes |series=Genetics of multifactorial diseases |language=en |volume=30 |issue=6 |pages=397–403 |doi=10.1016/j.mcp.2016.09.001 |issn=0890-8508}}</ref> However, there also exist mutations that protect against Alzheimer's and lower the risk of onset, one example being the APOE e2 allele and even CLU.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" />While much research has been done in the field, there is a disproportionate amount of research done in underrepresented communities.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Massett |first=Holly A. |last2=Mitchell |first2=Alexandra K. |last3=Alley |first3=Leah |last4=Simoneau |first4=Elizabeth |last5=Burke |first5=Panne |last6=Han |first6=Sae H. |last7=Gallop-Goodman |first7=Gerda |last8=McGowan |first8=Melissa |date=2021-06-29 |editor-last=Gleason |editor-first=Carey |title=Facilitators, Challenges, and Messaging Strategies for Hispanic/Latino Populations Participating in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Clinical Research: A Literature Review |url=https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-201463 |journal=Journal of Alzheimer's Disease |volume=82 |issue=1 |pages=107–127 |doi=10.3233/JAD-201463}}</ref> The Hispanic and Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer's Disease and underrepresented in clinical research.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Marquez |first=David X. |last2=Perez |first2=Adriana |last3=Johnson |first3=Julene K. |last4=Jaldin |first4=Michelle |last5=Pinto |first5=Juan |last6=Keiser |first6=Sahru |last7=Tran |first7=Thi |last8=Martinez |first8=Paula |last9=Guerrero |first9=Javier |last10=Portacolone |first10=Elena |date=26 July 2022 |title=Increasing engagement of Hispanics/Latinos in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/trc2.12331 |journal=Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions |language=en |volume=8 |issue=1 |doi=10.1002/trc2.12331 |issn=2352-8737 |pmc= |

There is a large genetic component to Alzheimer's disease, with mutations in the [[Amyloid-beta precursor protein|amyloid precursor protein (APP)]], [[Apolipoprotein E|apolipoprotein E (APOE)]], [[PSEN1|presenilin 1 (PSEN1)]], [[PSEN2|presenilin-2]] (PSEN-2), [[BIN1|bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1]]), [[TREM2]], [[SORL1]], and [[Clusterin|Clusterin (CLU)]] genes increasing one's risk to develop the condition.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Breijyeh |first=Zeinab |last2=Karaman |first2=Rafik |date=2020-12-08 |title=Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7764106/ |journal=Molecules |volume=25 |issue=24 |pages=5789 |doi=10.3390/molecules25245789 |issn=1420-3049 |pmc=7764106 |pmid=33302541}}</ref><ref name=":20">{{Cite journal |last=Tosto |first=Giuseppe |last2=Reitz |first2=Christiane |date=2016-12-01 |title=Genomics of Alzheimer's disease: Value of high-throughput genomic technologies to dissect its etiology |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890850816300743 |journal=Molecular and Cellular Probes |series=Genetics of multifactorial diseases |language=en |volume=30 |issue=6 |pages=397–403 |doi=10.1016/j.mcp.2016.09.001 |issn=0890-8508}}</ref> However, there also exist mutations that protect against Alzheimer's and lower the risk of onset, one example being the APOE e2 allele and even CLU.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" />While much research has been done in the field, there is a disproportionate amount of research done in underrepresented communities.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Massett |first=Holly A. |last2=Mitchell |first2=Alexandra K. |last3=Alley |first3=Leah |last4=Simoneau |first4=Elizabeth |last5=Burke |first5=Panne |last6=Han |first6=Sae H. |last7=Gallop-Goodman |first7=Gerda |last8=McGowan |first8=Melissa |date=2021-06-29 |editor-last=Gleason |editor-first=Carey |title=Facilitators, Challenges, and Messaging Strategies for Hispanic/Latino Populations Participating in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Clinical Research: A Literature Review |url=https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-201463 |journal=Journal of Alzheimer's Disease |volume=82 |issue=1 |pages=107–127 |doi=10.3233/JAD-201463}}</ref> The Hispanic and Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer's Disease and underrepresented in clinical research.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Marquez |first=David X. |last2=Perez |first2=Adriana |last3=Johnson |first3=Julene K. |last4=Jaldin |first4=Michelle |last5=Pinto |first5=Juan |last6=Keiser |first6=Sahru |last7=Tran |first7=Thi |last8=Martinez |first8=Paula |last9=Guerrero |first9=Javier |last10=Portacolone |first10=Elena |date=26 July 2022 |title=Increasing engagement of Hispanics/Latinos in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/trc2.12331 |journal=Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions |language=en |volume=8 |issue=1 |doi=10.1002/trc2.12331 |issn=2352-8737 |pmc=9322823 |pmid=35910673}}</ref><ref name=":1" /> A major contributing factor to this phenomenon is the socioeconomic status of those within these communities.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":1" /> Additionally, several of the genetic mutations associated with Alzheimer's have been shown to affect this population differently, when compared to white and black patients.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":13">{{Cite journal |last=Liu |first=Chia-Chen |last2=Kanekiyo |first2=Takahisa |last3=Xu |first3=Huaxi |last4=Bu |first4=Guojun |date=February 2013 |title=Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms, and therapy |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3726719/ |journal=Nature reviews. Neurology |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=106–118 |doi=10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263 |issn=1759-4758 |pmc=3726719 |pmid=23296339}}</ref><ref name=":7" /> |

||

== Alzheimer's Disease (AD) == |

== Alzheimer's Disease (AD) == |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==== Mild Cognitive Impairment ==== |

==== Mild Cognitive Impairment ==== |

||

Mild Cognitive impairment (MCI) precedes the overt diagnosis of AD.<ref name=":0" /> <ref>{{Cite journal |last=Li |first=Lanlan |last2=Yu |first2=Xianfeng |last3=Sheng |first3=Can |last4=Jiang |first4=Xueyan |last5=Zhang |first5=Qi |last6=Han |first6=Ying |last7=Jiang |first7=Jiehui |date=2022-09-15 |title=A review of brain imaging biomarker genomics in Alzheimer’s disease: implementation and perspectives |url=https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-022-00315-z |journal=Translational Neurodegeneration |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=42 |doi=10.1186/s40035-022-00315-z |issn=2047-9158 |pmc= |

Mild Cognitive impairment (MCI) precedes the overt diagnosis of AD.<ref name=":0" /> <ref>{{Cite journal |last=Li |first=Lanlan |last2=Yu |first2=Xianfeng |last3=Sheng |first3=Can |last4=Jiang |first4=Xueyan |last5=Zhang |first5=Qi |last6=Han |first6=Ying |last7=Jiang |first7=Jiehui |date=2022-09-15 |title=A review of brain imaging biomarker genomics in Alzheimer’s disease: implementation and perspectives |url=https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-022-00315-z |journal=Translational Neurodegeneration |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=42 |doi=10.1186/s40035-022-00315-z |issn=2047-9158 |pmc=9476275 |pmid=36109823}}</ref><ref name=":23">{{Cite journal |last=Langa |first=Kenneth M. |last2=Levine |first2=Deborah A. |date=2014-12-17 |title=The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25514304/ |journal=JAMA |volume=312 |issue=23 |pages=2551–2561 |doi=10.1001/jama.2014.13806 |issn=1538-3598 |pmc=4269302 |pmid=25514304}}</ref> To be diagnosed with MCI a patient must show memory impairment, a progressive decline in cognitive abilities without presenting symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and behavioral or language disorders.<ref name=":23" /> However, it is important to understand the effect of demographic and linguistic factors in diagnosing MCI.<ref name=":24">{{Cite journal |last=Briceño |first=Emily M. |last2=Mehdipanah |first2=Roshanak |last3=Gonzales |first3=Xavier Fonz |last4=Langa |first4=Kenneth M. |last5=Levine |first5=Deborah A. |last6=Garcia |first6=Nelda M. |last7=Longoria |first7=Ruth |last8=Giordani |first8=Bruno J. |last9=Heeringa |first9=Steven G. |last10=Morgenstern |first10=Lewis B. |date=13 April 2020 |title=Neuropsychological assessment of mild cognitive impairment in Latinx adults: A scoping review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32281811/ |journal=Neuropsychology |volume=34 |issue=5 |pages=493–510 |doi=10.1037/neu0000628 |issn=1931-1559 |pmc=8209654 |pmid=32281811}}</ref><ref name=":25">{{Cite journal |last=Briceño |first=E |last2=Mehdipanah |first2=R |last3=Gonzales |first3=X |last4=Langa |first4=K |last5=Levine |first5=D |last6=Garcia |first6=N |last7=Longoria |first7=R |last8=Giordani |first8=B |last9=Heeringa |first9=S |last10=Morgenstern |first10=L |date=2019-08-30 |title=Culture and Diagnosis of MCI in Hispanics: A Literature Review |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acz029.06 |journal=Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology |volume=34 |issue=7 |pages=1239–1239 |doi=10.1093/arclin/acz029.06 |issn=1873-5843}}</ref> Studies show that older Hispanic/Latinos exhibit a higher prevalence of dementia than caucasians. <ref>{{Cite journal |last=González |first=Hector M. |last2=Tarraf |first2=Wassim |last3=Fornage |first3=Myriam |last4=González |first4=Kevin A. |last5=Chai |first5=Albert |last6=Youngblood |first6=Marston |last7=Abreu |first7=Maria de los Angeles |last8=Zeng |first8=Donglin |last9=Thomas |first9=Sonia |last10=Talavera |first10=Gregory A. |last11=Gallo |first11=Linda C. |last12=Kaplan |first12=Robert |last13=Daviglus |first13=Martha L. |last14=Schneiderman |first14=Neil |date=2019-12-01 |title=A research framework for cognitive aging and Alzheimer's disease among diverse US Latinos: Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos—Investigation of Neurocognitive Aging (SOL-INCA) |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1552526019353622 |journal=Alzheimer's & Dementia |language=en |volume=15 |issue=12 |pages=1624–1632 |doi=10.1016/j.jalz.2019.08.192 |issn=1552-5260}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Arévalo |first=Sandra P. |last2=Kress |first2=Jennifer |last3=Rodriguez |first3=Francisca S. |date=April 2020 |title=Validity of Cognitive Assessment Tools for Older Adult Hispanics: A Systematic Review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31886524/ |journal=Journal of the American Geriatrics Society |volume=68 |issue=4 |pages=882–888 |doi=10.1111/jgs.16300 |issn=1532-5415 |pmid=31886524}}</ref> However, many studies of cognition include subjects for whom English might not be the primary language requiring use of a translator or interpreter; nor do the studies report the methodology used for neuropsychological assessment of non-native English speakers. <ref name=":24" /><ref name=":25" /> As a result, much work remains to be done in understanding MCI in Hispanics/Latinos and its role in Alzheimer's within the population. |

||

[[File:PiB_PET_Images_AD.jpg|thumb|432x432px|PiB-PET scan of an AD patient (left) compared to an age-matched control (right). Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) is easily taken up into the brains of Alzheimer's patients and is used to detect Amyloid beta. Brain regions that are colored red and yellow correspond to a high concentration of PiB, suggesting high amounts of amyloid deposit]] |

[[File:PiB_PET_Images_AD.jpg|thumb|432x432px|PiB-PET scan of an AD patient (left) compared to an age-matched control (right). Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) is easily taken up into the brains of Alzheimer's patients and is used to detect Amyloid beta. Brain regions that are colored red and yellow correspond to a high concentration of PiB, suggesting high amounts of amyloid deposit]] |

||

<ref name=":24" /><ref name=":25" /> |

<ref name=":24" /><ref name=":25" /> |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

==== The SORL1 Gene ==== |

==== The SORL1 Gene ==== |

||

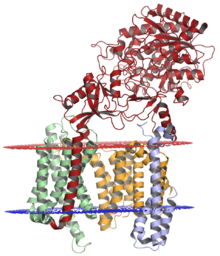

[[File:Human SORL1 in complex with A-beta derived peptide.jpg|thumb|250x250px|The X-ray crystallography structure of human SORL1 in complex with A-beta derived peptide]] |

[[File:Human SORL1 in complex with A-beta derived peptide.jpg|thumb|250x250px|The X-ray crystallography structure of human SORL1 in complex with A-beta derived peptide]] |

||

Sortilin-related receptor 1 (SORL1) is a 250-kDa membrane protein with seven distinct domains that make it a member of two receptor families: the [[LDL receptor|low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family]] of ApoE receptors and the vacuolar protein sorting 10 (VPS10) domain receptor family.<ref name=":27" /><ref name=":20" /> In humans, the SORL1 expresses on chromosome 11, specifically q232-q24.2.<ref name=":27" /> As a protein SORL1 is highly expressed in the brain, specifically in hippocampal neurons and Purkinje cells.<ref name=":27" /> Intracellularly, SOLR1 is typically expressed in early endosomes and the trans-Golgi network.<ref name=":27" /> Concerning its role in AD, SORL1 is involved in the intracellular trafficking of APP.<ref name=":27" /><ref name=":20" /> The protein can bind to APP expressed in endosomes and allow APP to be transported back to the cell surface—this prevents amyloidogenic processing and the production of cytotoxic Aβ42.<ref name=":27" /> <ref name=":28">{{Cite journal |last=Vardarajan |first=Badri N. |last2=Zhang |first2=Yalun |last3=Lee |first3=Joseph H. |last4=Cheng |first4=Rong |last5=Bohm |first5=Christopher |last6=Ghani |first6=Mahdi |last7=Reitz |first7=Christiane |last8=Reyes-Dumeyer |first8=Dolly |last9=Shen |first9=Yufeng |last10=Rogaeva |first10=Ekaterina |last11=St George-Hyslop |first11=Peter |last12=Mayeux |first12=Richard |date=7 November 2014 |title=Coding mutations in SORL 1 and Alzheimer disease: SORL1 Variants and AD |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.24305 |journal=Annals of Neurology |language=en |volume=77 |issue=2 |pages=215–227 |doi=10.1002/ana.24305 |pmc= |

Sortilin-related receptor 1 (SORL1) is a 250-kDa membrane protein with seven distinct domains that make it a member of two receptor families: the [[LDL receptor|low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family]] of ApoE receptors and the vacuolar protein sorting 10 (VPS10) domain receptor family.<ref name=":27" /><ref name=":20" /> In humans, the SORL1 expresses on chromosome 11, specifically q232-q24.2.<ref name=":27" /> As a protein SORL1 is highly expressed in the brain, specifically in hippocampal neurons and Purkinje cells.<ref name=":27" /> Intracellularly, SOLR1 is typically expressed in early endosomes and the trans-Golgi network.<ref name=":27" /> Concerning its role in AD, SORL1 is involved in the intracellular trafficking of APP.<ref name=":27" /><ref name=":20" /> The protein can bind to APP expressed in endosomes and allow APP to be transported back to the cell surface—this prevents amyloidogenic processing and the production of cytotoxic Aβ42.<ref name=":27" /> <ref name=":28">{{Cite journal |last=Vardarajan |first=Badri N. |last2=Zhang |first2=Yalun |last3=Lee |first3=Joseph H. |last4=Cheng |first4=Rong |last5=Bohm |first5=Christopher |last6=Ghani |first6=Mahdi |last7=Reitz |first7=Christiane |last8=Reyes-Dumeyer |first8=Dolly |last9=Shen |first9=Yufeng |last10=Rogaeva |first10=Ekaterina |last11=St George-Hyslop |first11=Peter |last12=Mayeux |first12=Richard |date=7 November 2014 |title=Coding mutations in SORL 1 and Alzheimer disease: SORL1 Variants and AD |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.24305 |journal=Annals of Neurology |language=en |volume=77 |issue=2 |pages=215–227 |doi=10.1002/ana.24305 |pmc=4367199 |pmid=25382023}}</ref> Moreover, SOR1 has been shown to facilitate cholesterol transport through its tendency to bind to APOE-lipoprotein complexes.<ref name=":27" /> Strong disease-linked polymorphisms in SORL1 combine with its role in APP trafficking render SORL1 a biomarker of strong interest for LOAD. <ref name=":27" /><ref name=":28" /> Decreased levels of SOLR1 transcript and protein have been observed in the brains of AD patients. |

||

Analysis of SORL1 polymorphisms in the Hispanic/Latino population using GWAS and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have shown that several SORL1 mutations are seen in Caribbean Hispanics.<ref name=":20" /><ref name=":28" /> Two rare polymorphisms in SORL1 associated with AD were observed in this population, rs117260922-E270K and rs143571823-T947M, as well as a common variant (rs2298813-A528T) ''.''<ref name=":20" /><ref name=":28" /> However, these polymorphisms are not specific to Hispanics/Latinos as they are also observed in non-Hispanic white individuals.<ref name=":20" /> |

Analysis of SORL1 polymorphisms in the Hispanic/Latino population using GWAS and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have shown that several SORL1 mutations are seen in Caribbean Hispanics.<ref name=":20" /><ref name=":28" /> Two rare polymorphisms in SORL1 associated with AD were observed in this population, rs117260922-E270K and rs143571823-T947M, as well as a common variant (rs2298813-A528T) ''.''<ref name=":20" /><ref name=":28" /> However, these polymorphisms are not specific to Hispanics/Latinos as they are also observed in non-Hispanic white individuals.<ref name=":20" /> |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

==== Clusterin ==== |

==== Clusterin ==== |

||

Clusterin (CLU), also known as apolipoprotein J, is an 82 kDa glycoprotein protein that is located on chromosome 8. <ref name=":6" /><ref name=":34">{{Cite journal |last=Foster |first=Evangeline M. |last2=Dangla-Valls |first2=Adrià |last3=Lovestone |first3=Simon |last4=Ribe |first4=Elena M. |last5=Buckley |first5=Noel J. |date=2019 |title=Clusterin in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Genetics, and Lessons From Other Pathologies |url=https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2019.00164 |journal=Frontiers in Neuroscience |volume=13 |doi=10.3389/fnins.2019.00164/full |issn=1662-453X}}</ref><ref name=":21" /> It has multiple physiological functions, some examples being lipid transport, immune modulation, and cell death.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /> Additionally, CLU is known to have the ability to clear amyloid beta peptides and prevent their aggregation—suggesting that CLU has a neuroprotective effect.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /><ref name=":6" /> However, there exists a contradiction in the literature, as, GWAS studies have shown that CLU is upregulated in the plasma, CSF, hippocampus, and cortex of Alzheimer's patients.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /><ref name=":6" /> One theory that explains this is AD patients have a CLU variant that results in a downregulation of CLU early in life, increasing their risk of developing Alzheimer's.<ref name=":21" /> However, when they reach old age, their body tries to compensate by producing an excess of CLU.<ref name=":21" /> This phenomenon, paired with genetic studies, has made CLU the third most significant risk factor for LOAD—which has pushed researchers to find variants associated with Alzheimer's.<ref name=":34" /> Two CLU variants of interest, that are associated with reduced Alzheimer's frequency, are rs11136000 and rs9331896. <ref name=":21" /> In terms of how CLU is related to Alzheimer's risk in the Hispanic/Latino community, not much has been uncovered.<ref name=":35">{{Cite journal |last=Du |first=Wenjin |last2=Tan |first2=Jiping |last3=Xu |first3=Wei |last4=Chen |first4=Jinwen |last5=Wang |first5=Luning |date=2016-11-01 |title=Association between clusterin gene polymorphism rs11136000 and late‑onset Alzheimer's disease susceptibility: A review and meta‑analysis of case‑control studies |url=https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2016.3734 |journal=Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine |volume=12 |issue=5 |pages=2915–2927 |doi=10.3892/etm.2016.3734 |issn=1792-0981 |pmc= |

Clusterin (CLU), also known as apolipoprotein J, is an 82 kDa glycoprotein protein that is located on chromosome 8. <ref name=":6" /><ref name=":34">{{Cite journal |last=Foster |first=Evangeline M. |last2=Dangla-Valls |first2=Adrià |last3=Lovestone |first3=Simon |last4=Ribe |first4=Elena M. |last5=Buckley |first5=Noel J. |date=2019 |title=Clusterin in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Genetics, and Lessons From Other Pathologies |url=https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2019.00164 |journal=Frontiers in Neuroscience |volume=13 |doi=10.3389/fnins.2019.00164/full |issn=1662-453X}}</ref><ref name=":21" /> It has multiple physiological functions, some examples being lipid transport, immune modulation, and cell death.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /> Additionally, CLU is known to have the ability to clear amyloid beta peptides and prevent their aggregation—suggesting that CLU has a neuroprotective effect.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /><ref name=":6" /> However, there exists a contradiction in the literature, as, GWAS studies have shown that CLU is upregulated in the plasma, CSF, hippocampus, and cortex of Alzheimer's patients.<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":34" /><ref name=":6" /> One theory that explains this is AD patients have a CLU variant that results in a downregulation of CLU early in life, increasing their risk of developing Alzheimer's.<ref name=":21" /> However, when they reach old age, their body tries to compensate by producing an excess of CLU.<ref name=":21" /> This phenomenon, paired with genetic studies, has made CLU the third most significant risk factor for LOAD—which has pushed researchers to find variants associated with Alzheimer's.<ref name=":34" /> Two CLU variants of interest, that are associated with reduced Alzheimer's frequency, are rs11136000 and rs9331896. <ref name=":21" /> In terms of how CLU is related to Alzheimer's risk in the Hispanic/Latino community, not much has been uncovered.<ref name=":35">{{Cite journal |last=Du |first=Wenjin |last2=Tan |first2=Jiping |last3=Xu |first3=Wei |last4=Chen |first4=Jinwen |last5=Wang |first5=Luning |date=2016-11-01 |title=Association between clusterin gene polymorphism rs11136000 and late‑onset Alzheimer's disease susceptibility: A review and meta‑analysis of case‑control studies |url=https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2016.3734 |journal=Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine |volume=12 |issue=5 |pages=2915–2927 |doi=10.3892/etm.2016.3734 |issn=1792-0981 |pmc=5103725 |pmid=27882096}}</ref> One study attempted to find an association between the CLU rs11136000 variant and LOAD in populations of African or Hispanic descent, but no association was found.<ref name=":35" /> |

||

=== Comorbidities === |

=== Comorbidities === |

||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

==== Hypertension ==== |

==== Hypertension ==== |

||

[[File:Hypertension ranges chart.png|thumb|440x440px|The clinical stages of hypertension]][[Hypertension]] is a condition characterized by persistently high blood pressure in one's systemic arteries.<ref name=":14">{{Cite journal |last=Oparil |first=Suzanne |last2=Acelajado |first2=Maria Czarina |last3=Bakris |first3=George L. |last4=Berlowitz |first4=Dan R. |last5=Cífková |first5=Renata |last6=Dominiczak |first6=Anna F. |last7=Grassi |first7=Guido |last8=Jordan |first8=Jens |last9=Poulter |first9=Neil R. |last10=Rodgers |first10=Anthony |last11=Whelton |first11=Paul K. |date=2018-03-22 |title=Hypertension |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6477925/ |journal=Nature reviews. Disease primers |volume=4 |pages=18014 |doi=10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 |issn=2056-676X |pmc=6477925 |pmid=29565029}}</ref><ref name=":15">{{Cite journal |last=Mills |first=Katherine T |last2=Stefanescu |first2=Andrei |last3=He |first3=Jiang |date=April 2020 |title=The global epidemiology of hypertension |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7998524/ |journal=Nature reviews. Nephrology |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=223–237 |doi=10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2 |issn=1759-5061 |pmc=7998524 |pmid=32024986}}</ref> Two measurements are taken as a ratio to quantify blood pressure: [[Systolic blood pressure|systolic]] and [[Diastolic blood pressure|diastolic]] blood pressure. <ref name=":15" /> A patient is diagnosed as hypertensive when their systolic blood pressure is greater than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mmHg. However, not many people with hypertension are aware that they have the condition.<ref name=":15" /><ref name=":14" /> In 2010, 31.1% of adults worldwide had hypertension, but only 45.6% of them were aware they had the condition.<ref name=":15" /> This problem of hypertension is more apparent in the Hispanic/Latino population, as in 2008 the incidence rate of hypertension for Hispanic adults aged 45-84 was 65.7%, compared to 56.8% for non-Hispanic whites of the same age. <ref name=":1" /><ref name=":16">{{Cite journal |last=Guzman |first=Nicolas J. |date=2012-06-01 |title=Epidemiology and Management of Hypertension in the Hispanic Population |url=https://doi.org/10.2165/11631520-000000000-00000 |journal=American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs |language=en |volume=12 |issue=3 |pages=165–178 |doi=10.2165/11631520-000000000-00000 |issn=1179-187X |pmc= |

[[File:Hypertension ranges chart.png|thumb|440x440px|The clinical stages of hypertension]][[Hypertension]] is a condition characterized by persistently high blood pressure in one's systemic arteries.<ref name=":14">{{Cite journal |last=Oparil |first=Suzanne |last2=Acelajado |first2=Maria Czarina |last3=Bakris |first3=George L. |last4=Berlowitz |first4=Dan R. |last5=Cífková |first5=Renata |last6=Dominiczak |first6=Anna F. |last7=Grassi |first7=Guido |last8=Jordan |first8=Jens |last9=Poulter |first9=Neil R. |last10=Rodgers |first10=Anthony |last11=Whelton |first11=Paul K. |date=2018-03-22 |title=Hypertension |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6477925/ |journal=Nature reviews. Disease primers |volume=4 |pages=18014 |doi=10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 |issn=2056-676X |pmc=6477925 |pmid=29565029}}</ref><ref name=":15">{{Cite journal |last=Mills |first=Katherine T |last2=Stefanescu |first2=Andrei |last3=He |first3=Jiang |date=April 2020 |title=The global epidemiology of hypertension |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7998524/ |journal=Nature reviews. Nephrology |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=223–237 |doi=10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2 |issn=1759-5061 |pmc=7998524 |pmid=32024986}}</ref> Two measurements are taken as a ratio to quantify blood pressure: [[Systolic blood pressure|systolic]] and [[Diastolic blood pressure|diastolic]] blood pressure. <ref name=":15" /> A patient is diagnosed as hypertensive when their systolic blood pressure is greater than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mmHg. However, not many people with hypertension are aware that they have the condition.<ref name=":15" /><ref name=":14" /> In 2010, 31.1% of adults worldwide had hypertension, but only 45.6% of them were aware they had the condition.<ref name=":15" /> This problem of hypertension is more apparent in the Hispanic/Latino population, as in 2008 the incidence rate of hypertension for Hispanic adults aged 45-84 was 65.7%, compared to 56.8% for non-Hispanic whites of the same age. <ref name=":1" /><ref name=":16">{{Cite journal |last=Guzman |first=Nicolas J. |date=2012-06-01 |title=Epidemiology and Management of Hypertension in the Hispanic Population |url=https://doi.org/10.2165/11631520-000000000-00000 |journal=American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs |language=en |volume=12 |issue=3 |pages=165–178 |doi=10.2165/11631520-000000000-00000 |issn=1179-187X |pmc=3624012 |pmid=22583147}}</ref> Moreover, Hispanic/Latinos are more likely to be unaware of their condition, compared to non-Hispanics, and therefore, be less likely to seek treatment. <ref name=":16" /><ref name=":15" /> Patients need to seek treatment as being hypertensive increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, cognitive deficit and Alzheimer's Disease.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":14" /> Fortunately, hypertension is a preventable condition and can be offset by lifestyle changes (i.e. weight loss and exercise) and pharmacological intervention<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":14" />. Researchers are even pursuing the use of antihypertensive drugs for the treatment of dementia and Alzheimer's. <ref name=":11" /> |

||

==== Diabetes ==== |

==== Diabetes ==== |

||

Revision as of 12:07, 8 December 2022

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (December 2022) |

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the presence of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.[1] It is one of the most common causes of dementia, leading to memory loss, cognitive deficits, and behavioral issues.[1] Currently, 5.4 million Americans have been diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease, and this number is projected to reach 15-22 million by 2050.[2][3] Hispanics and Latinos account for 55 million of the current population and this population is projected to rise to 97 million, accounting for 25% of the U.S. population, in 2050.[3] Moreover, in 2012 379,000 Hispanic/Latinos were diagnosed with Alzheimer's, and by 2060 this number is projected to increase to 3.5 million by 2060.[3]

There is a large genetic component to Alzheimer's disease, with mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), apolipoprotein E (APOE), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin-2 (PSEN-2), bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1), TREM2, SORL1, and Clusterin (CLU) genes increasing one's risk to develop the condition.[2][4][5] However, there also exist mutations that protect against Alzheimer's and lower the risk of onset, one example being the APOE e2 allele and even CLU.[4][2]While much research has been done in the field, there is a disproportionate amount of research done in underrepresented communities.[6] The Hispanic and Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by Alzheimer's Disease and underrepresented in clinical research.[7][6] A major contributing factor to this phenomenon is the socioeconomic status of those within these communities.[3][6] Additionally, several of the genetic mutations associated with Alzheimer's have been shown to affect this population differently, when compared to white and black patients.[3][8][2]

Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60% of all cases, and is the sixth leading cause of death in the elderly.[9][10]The disease typically presents itself with intracellular aggregation of hyper-phosphorylated tau, forming neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and the extracellular aggregation of amyloid beta, forming amyloid beta plaques.[4] The pathology of this disease, however, does not differ across ethnic groups.[4]

Alzheimer's Disease in the Hispanic/Latino Population

Hispanics and Latinos make up 18% of the U.S. population, however, like other racial minorities in the U.S. they are underrepresented in clinical research.[6][11] The National Institute of Health (NIH) reported that Hispanic and Latinos accounted for less than 8% of reported clinical trial participants.[3] While this population makes up a substantial portion of the population, it is the diversity of the group that makes it difficult to conduct clinical research. The Hispanic/Latino population includes many people from different countries, and with this diverse background come different characteristics and comorbidities associated with Alzheimer's.[3] The issue of representation is made more apparent considering that these Hispanic and Latinos are shown to have a higher prevalence of Alzheimer's compared to non-White Hispanics.[3][6] Studies estimate that 12% of older Hispanic and Latino adults were diagnosed with Alzheimer's, the highest proportion compared to all other ethnic groups.[6] As the fastest-growing population in the U.S., studies have predicted that Hispanic/Latino seniors, those who are 65 and older, will have the largest rise in Alzheimer's and dementia cases compared to other populations.[3] The lack of research on Alzheimer's disease was recognized in 2011, resulting in the National Alzheimer's Project Act being signed into law. One goal of this act is for The National Institute of Aging to improve the inclusion of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer's research and clinical trials.[6] This effort will ensure that the pathology, etiology, and genetic component of Alzheimer's becomes better understood and improve the quality of care.[6]

Types of Alzheimer's Disease

There exist two types of Alzheimer's disease: familial Alzheimer's, also called early on-set (EOAD), and sporadic Alzheimer's, also called late-onset (LOAD)[2][12]. EOAD is the less common of the two, accounting for 5-10%, and patients with EOAD are typically diagnosed with familial AD before they turn 65 years old.[2][12] LOAD is more common and accounts for 90% of Alzheimer's cases and its patients experience onset after they turn 65. [10][4] EOAD has been shown to have 2 types of inheritance patterns: mendelian (mEOAD) and non-mendelian (nmEOAD) patterns.[2] The three main genes that implicated in familial Alzheimer's are amyloid precursor protein (APP), Presenilin-1 (PSEN-1), presenilin-2 (PSEN-2). [2][12][4] Onset of sporadic Alzheimer's, however, has both genetic and environmental risk factors.[12] Some genes of interest in LOAD are the APOE gene, specifically the ApoE4 allele, bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1), SORL1, and clusterin (CLU).[2][4][13] [14] [5]

Pathology and Symptoms

Amyloid Beta Plaques and Neurofibrillary Tangles

Amyloid beta plaques and Neurofibrillary Tangles (NFTs) are the main pathological component of Alzheimer's.[4][15] Amyloid beta plaques form when the larger protein APP is trafficked to endosomes and is cleaved by beta-secretase (BACE), after which it

moves back to the cell surface to be cleaved by gamma-secretase.[4][5][15] This form of APP processing is known as the amyloidogenic pathway and under these conditions, the toxic Aβ42 peptide is produced.[4][16] Under non-pathological conditions, APP would be cleaved by alpha and gamma-secretase and undergo non-amyloidogenic processing.[15][16] NFTs form when protein tau, which is involved in microtubule stability, is hyperphosphorylated and aggregates with other p-tau monomers forming fibrils, oligomers, and eventually NFTs.[4]

Chronic Inflammation

Neuroinflammation is another pathological component of Alzheimer's pathology, and its importance is reflected by an observed increase in levels of inflammatory markers.[4][17] Researchers have also identified many genes linked to immune function that are risk factors for Alzheimer's, such as TREM2.[17] TREM2 are highly expressed in microglia, the immune cell of the brain, tying the progression of Alzheimer's with dysfunction in microglial activity.[18] Neuroinflammation, amyloid beta, and tau pathologies interact in Alzheimer's disease, which has led biomarkers of neuroinflammation to become an important subject of research.[17] Multiple biomarkers of inflammation exist.[19] For example, studies have found the neuroinflammatory marker YKL-40 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of Alzheimer's patients.[14][19] This protein increases years before the onset of Alzheimer's symptoms and correlates with other neurodegenerative biomarkers, which suggests a potential to predict disease progression.[19] While YKL-40 has not been shown to associate with the APOE -ε4 allele, there is research to link this biomarker to AD in the Hispanic population.[19]

Neurodegeneration

Along with the plaques and inflammation, patients with AD also suffer from neurodegeneration, characterized by loss of neurons and synaptic density.[15][4] As a result, the entire brain shrinks in volume (termed brain atrophy), the ventricles grow larger, and the hippocampus and cortex shrink in size.[4][15] As all these pathologies progress, patients begin to experience a decline in memory, cognitive abilities, and independence. The accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles and loss of synaptic fields correlate most closely with cognitive loss.[4]

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive impairment (MCI) precedes the overt diagnosis of AD.[1] [20][21] To be diagnosed with MCI a patient must show memory impairment, a progressive decline in cognitive abilities without presenting symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and behavioral or language disorders.[21] However, it is important to understand the effect of demographic and linguistic factors in diagnosing MCI.[22][23] Studies show that older Hispanic/Latinos exhibit a higher prevalence of dementia than caucasians. [24][25] However, many studies of cognition include subjects for whom English might not be the primary language requiring use of a translator or interpreter; nor do the studies report the methodology used for neuropsychological assessment of non-native English speakers. [22][23] As a result, much work remains to be done in understanding MCI in Hispanics/Latinos and its role in Alzheimer's within the population.

Brain Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a brain imaging technique that uses a small amount of radioactive substance, called a tracer, to measure energy use or a specific molecule in different brain regions.[26] In Alzheimer's research, tracers can be used to detect amyloid-beta and tau. Depending on the tracer used, the signal can be used to determine the presence of amyloid-beta plaques and NFTs.[26]

Biomarkers

Establishing biomarkers for Alzheimer's is vital for its early detection and possible prevention, as pathological changes occur years before symptoms become apparent.[4][14] Common biomarkers for AD include amyloid beta and hyperphosphorylated tau, both of which can be found in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).[4] Amyloid beta provides a biomarker of amyloid beta plaques, which form when APP cleavage results in an increase in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio.[4] Hyperphosphorylated tau serves as a biomarker of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), with the presence of NFTs indicating a disruption in microtubule stability and neuronal injury. [4] Researchers have begun investigating other markers in the CSF, such as markers of neuronal injury, like Visinin-Like-Protein-1 (VILIP-1), YKL-40, and Neurogranin (NGRN).[14] Due to the low use of CSF sampling in most countries, efforts have been made to study biomarkers in blood. [14] Through work on blood biomarkers, researchers have been able to find proteins that are elevated in Alzheimer's patients and have predictive potential.[14] The predictive potential of these plasma markers increases further when coupled with the presence of genetic risk factors, such as the APOE E4 allele.[27] Examples of plasma biomarkers include interleukin, TGF, and micro-RNA. [14]

Current genetic risk factors being considered for integration with biomarkers includes ApoE, PSEN1, Bin1, CLU, and SORL1.[13][5][4][2]

The APOE Gene

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a lipoprotein complex, comprised of 299 amino acids, that is mainly expressed in the brain and is involved in cholesterol metabolism, specifically in the intracellular and extracellular transport, delivery, and distribution.[13] APOE associates with high-density lipoproteins (HDL).[10] The gene for APOE is located on chromosome 19 and exhibits polymorphisms in the population defined by three alleles of APOE: 𝜀2, 𝜀3, and 𝜀4. [13] These alleles differ by only two single nucleotide polymorphisms in exon 4, rs429358 and rs7412 (amino-acid position 112 and 158). [4][13] APOE𝜀3 is the more common of the three and is present in 50-90% of the general population.[13] APOE 𝜀4 on the other hand is a risk factor for LOAD, increasing genetic risk up to 33-fold, depending on the population (see the table below).[16] It has been shown that 50% of LOAD patients have the 𝜀4 allele and that having even one copy of the 𝜀4 allele increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's by a factor of 4. [4][2][13] APOE 𝜀2 has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect with carriers of the allele showing a lower prevalence of AD.[13] The neuropathological effects of APOE ε4 are pleiotropic; APOE ε4 impairs uptake of cholesterol by neurons, promotes microglial dysfunction, promotes beta-amyloid aggregation and is enhances with cerebral angiopathy (CAA).[4][10] The increased incidence of AD associated with the APOE ε4 allele has been proposed to be directly linked to beta amyloid because it modulates Aβ aggregation and clearance, although increasing evidence points to a multitude of actions.[28]

| Population | APOE𝜀4 Association with AD |

|---|---|

| Caucasian | 12.5 |

| African Americans | 5.7 |

| Hispanic | 2.2 |

| Japanese | 33.1 |

While extensive research has been done on the APOE4 gene, the majority of Alzheimer's research has been done on non-Hispanic White individuals, with little representation from other ethnic and racial groups [6]. The research focusing on the Hispanic and Latino population, however, suggests that race is a key variable in assessing the risk of carrying the APOE ε4 allele in developing AD. [2][3][13] Genetic studies of the Hispanic and Latino population, show that the APOE ε4 allele exerts a much smaller effect on the risk of developing Alzheimer's Disease.[3] Some studies show that APOE ε4 exerts a more modest neurodegenerative risk in the population, other studies show virtually no risk associated with APOE ε4; the prevalence of AD seen in Caribbean Hispanics, compared to White Non-Hispanics, appears to be independent of APOE genotype.[3] Some studies even suggest that APOE ε4 has a neuroprotective effect— that the risk of developing EOAD in older Mexicans and Caribbean Hispanics with the APOEε4, was lower compared to White Non-Hispanics.[3] Many factors influence the disparity found in the effects of this gene, such as population stratification and the lack of representation in research.[3][6][11] The latter is supported by reports that attribute a lower prevalence of the APOE ε4 allele in Mexicans, compared to non-White Hispanics but having no allele frequency data for other Hispanic and Latino subgroups.[3]

The PSEN1 Gene

Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) is the catalytic subunit, comprised of 467 amino acids, of the transmembrane protein complex gamma-secretase.[29][10] It is this protein that cleaves amyloid precursor protein (APP), after beta-secretase cleavage, to produce Amyloid Beta.[10][29] The gene for PSE1N is located on chromosome 14, q24.2, and consists of 12 exons that encode a 467-amino-acid protein that is predicted to traverse the membrane 6 to 10 times.[10] Over 200 pathogenic mutations of this protein exist, many of which account for 18% to 50% of autosomal dominant EOAD cases.[13][10][30] PSEN1 mutations increase the risk of developing AD by increasing the production of amyloid beta-42, compared to amyloid beta-40.[10] Unlike APOE4, PSEN1 mutations tend to have a clear pathological effect in Hispanics and Latinos and tend to express region-specific mutations.[3] Puerto Ricans have a G206A mutation that causes familial AD, Cuban families diagnosed with EAOD commonly exhibit a L174M, mutation, Mexican families exhibit L171P and A431E mutations, and Colombian families exhibit an E280A mutation.[3]

The BIN1 Gene

Bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1) is a widely expressed Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs (BAR) adaptor protein that is located on chromosome 2, q14.3, and contains 20 exons.[16] BIN1 mainly regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Due to a large number of exons, this gene is subject to alternative splicing, with the major forms varying in the splicing of exons 6a, 10, 12, and 13.[16] Genetic studies indicate that dysfunction in BIN1 is the second most important risk factor for AD.[4][16] The mechanism through which BIN1 contributes to AD, though, is unclear. Studies suggest a range of possible reasons that BIN1 is associated with AD including interactions of BIN1 with the microtubule-associated proteins (i.e. CLIP170), endosomal trafficking of APP and APOE by BIN1, and BIN1 mediated regulation of inflammation through the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1). [16] The interaction of BIN1 and tau might also be important because elevated levels of BIN1 are associated with increased AD risk through tau load; this result is suggested because of studies of the functional rs59335482 variant.[16] Additionally, endocytic trafficking of APP by BIN1 could be important because trafficking determines if APP will undergo the non-amyloidogenic or the amyloidogenic pathway.[16] For example, if APP is transported to the endosome, it will likely be cleaved by beta-secretase and undergo amyloidogenic processing, but if it accumulates on the cell surface it will be likely cleaved by alpha-secretase and undergo non-amyloidogenic processing.[16] Lastly, BIN1 facilitates the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism by regulating the expression of the rate-limiting enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1). [16] For the IDO1 mechanism, increased BIN1 expression could increase levels of a toxic tryptophan derivative IDO1.[16] These metabolites have been suggested to be involved in AD pathology and cognitive decline, as they co-localize with the plaques and NFTs in patient brains.[16]

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the Hispanic/Latino population indicate that polymorphisms in the BIN1, ABAC7 and CD2AP genes are more significant in Caribbean Hispanics.[5] For instance, one BIN1 mutation that has been explored in this Caribbean Hispanics however, is rs13426725. [16]Other variants that increase the risk of AD include rs6733839.[16]

The SORL1 Gene

Sortilin-related receptor 1 (SORL1) is a 250-kDa membrane protein with seven distinct domains that make it a member of two receptor families: the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family of ApoE receptors and the vacuolar protein sorting 10 (VPS10) domain receptor family.[28][5] In humans, the SORL1 expresses on chromosome 11, specifically q232-q24.2.[28] As a protein SORL1 is highly expressed in the brain, specifically in hippocampal neurons and Purkinje cells.[28] Intracellularly, SOLR1 is typically expressed in early endosomes and the trans-Golgi network.[28] Concerning its role in AD, SORL1 is involved in the intracellular trafficking of APP.[28][5] The protein can bind to APP expressed in endosomes and allow APP to be transported back to the cell surface—this prevents amyloidogenic processing and the production of cytotoxic Aβ42.[28] [32] Moreover, SOR1 has been shown to facilitate cholesterol transport through its tendency to bind to APOE-lipoprotein complexes.[28] Strong disease-linked polymorphisms in SORL1 combine with its role in APP trafficking render SORL1 a biomarker of strong interest for LOAD. [28][32] Decreased levels of SOLR1 transcript and protein have been observed in the brains of AD patients.

Analysis of SORL1 polymorphisms in the Hispanic/Latino population using GWAS and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have shown that several SORL1 mutations are seen in Caribbean Hispanics.[5][32] Two rare polymorphisms in SORL1 associated with AD were observed in this population, rs117260922-E270K and rs143571823-T947M, as well as a common variant (rs2298813-A528T) .[5][32] However, these polymorphisms are not specific to Hispanics/Latinos as they are also observed in non-Hispanic white individuals.[5]

ATP Binding Cassette Transporters

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette transporters are a large family of ABC transporters that regulates the efflux of cholesterol in neuronal cells.[4] Two members of the ATP binding cassette transporter family have been implicated in LOAD: ABC Subfamily A Member 1 (ABCA1) and ABC Subfamily A member 7 (ABCA7). [5][2][16] ABCA1 is a 220-240 kDa protein whose gene is located in chromosome 9q31.1[33] Its putative role in AD is tied to its role in stabilizing ApoE lipidation and degrading amyloid beta expressed in the brain.[5][4] ABCA7 exhibits strong genetic linkage to AD; it is involved in lipid and cholesterol processing, as well as immune system function.[34][16] ABCA7 exhibits tighter association with amyloid deposition than ABCA1.[34] However, the research on ABCA7 mutations in the Hispanic/Latino population is a bit controversial. Some studies propose that mutations in ABCA7 are more common in Caucasian patients, whereas Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to express a BIN1 mutation.[5] But researchers have still found polymorphisms specific to this population, one example being a 44-base pair frameshift deletion in ABCA7 increases AD risk in African Americans and Caribbean Hispanics.[2]

Clusterin

Clusterin (CLU), also known as apolipoprotein J, is an 82 kDa glycoprotein protein that is located on chromosome 8. [4][35][14] It has multiple physiological functions, some examples being lipid transport, immune modulation, and cell death.[14][35] Additionally, CLU is known to have the ability to clear amyloid beta peptides and prevent their aggregation—suggesting that CLU has a neuroprotective effect.[14][35][4] However, there exists a contradiction in the literature, as, GWAS studies have shown that CLU is upregulated in the plasma, CSF, hippocampus, and cortex of Alzheimer's patients.[14][35][4] One theory that explains this is AD patients have a CLU variant that results in a downregulation of CLU early in life, increasing their risk of developing Alzheimer's.[14] However, when they reach old age, their body tries to compensate by producing an excess of CLU.[14] This phenomenon, paired with genetic studies, has made CLU the third most significant risk factor for LOAD—which has pushed researchers to find variants associated with Alzheimer's.[35] Two CLU variants of interest, that are associated with reduced Alzheimer's frequency, are rs11136000 and rs9331896. [14] In terms of how CLU is related to Alzheimer's risk in the Hispanic/Latino community, not much has been uncovered.[36] One study attempted to find an association between the CLU rs11136000 variant and LOAD in populations of African or Hispanic descent, but no association was found.[36]

Comorbidities

With the growing Hispanic/Latino population, it becomes important to investigate diseases that increase the risk of developing dementia. Studies have shown that metabolic disorders, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, and depression can increase one's risk of developing Alzheimer's as well as increase the rate at which it progresses. [8][3][37] In the United States, 33% of the total population suffers from a metabolic disorder (i.e. diabetes and hypertension).[3] Unfortunately, Hispanic and Latino adults are at an increased risk, compared to other groups, to develop these conditions.[6] As of 2017, it has been reported that 35% of all Latinos suffer from an Alzheimer's comorbidity, with 17% suffering from diabetes and 25.4% suffering from hypertension.[3] The high prevalence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions is proposed to account for the higher risk of Alzheimer's Disease seen in Hispanics and Latinos.[3][6][11][37]

Hypertension

Hypertension is a condition characterized by persistently high blood pressure in one's systemic arteries.[38][39] Two measurements are taken as a ratio to quantify blood pressure: systolic and diastolic blood pressure. [39] A patient is diagnosed as hypertensive when their systolic blood pressure is greater than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mmHg. However, not many people with hypertension are aware that they have the condition.[39][38] In 2010, 31.1% of adults worldwide had hypertension, but only 45.6% of them were aware they had the condition.[39] This problem of hypertension is more apparent in the Hispanic/Latino population, as in 2008 the incidence rate of hypertension for Hispanic adults aged 45-84 was 65.7%, compared to 56.8% for non-Hispanic whites of the same age. [6][40] Moreover, Hispanic/Latinos are more likely to be unaware of their condition, compared to non-Hispanics, and therefore, be less likely to seek treatment. [40][39] Patients need to seek treatment as being hypertensive increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, cognitive deficit and Alzheimer's Disease.[3][6][37][38] Fortunately, hypertension is a preventable condition and can be offset by lifestyle changes (i.e. weight loss and exercise) and pharmacological intervention[37][38]. Researchers are even pursuing the use of antihypertensive drugs for the treatment of dementia and Alzheimer's. [37]

Diabetes

Type-II diabetes is a metabolic condition characterized by high blood sugar and defective insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells.[41] [42] A patient is diagnosed with diabetes when their fasting blood glucose levels are above 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or above 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dl) two hours after an oral dose of glucose. [42] As with hypertension, there is an observed racial bias with diabetes in the Hispanic/Latino population. [43] In the U.S., Hispanic/Latinos are reported to have a diabetes prevalence of 22.6%, compared to 113% in non-Hispanic whites.[43] This increased risk is associated with genetic factors, environmental factors (i.e. diet), and socioeconomic status. [40][44] Recently Alzheimer's has also been characterized as a metabolic disease of glucose regulation, as patients experience alterations in brain insulin responsiveness that leads to oxidative stress and inflammation. [43] Alzheimer's patients who demonstrate changes in cerebral glucose signaling are diagnosed with type three diabetes. [43] [45] The association that brought upon this new diagnosis is not without evidence, as older diabetic Mexican Americans are twice as likely to develop dementia than those without diabetes. [43] Additionally, it has been shown that the longer a patient is diabetic, the faster the rate of cognitive decline within the same and racial and age group. [43]

Lifestyle

Many of the comorbidities for Alzheimer's are also preventable through lifestyle changes, without the need for pharmacological intervention. [39][41] Hypertension can be treated by reducing sodium intake, increasing potassium intake, reducing alcohol consumption, and engaging in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week.[39] Similarly, diabetes can also be treated by increasing physical activity and changing diet. [41] Therefore, the same lifestyle changes are recommended for Alzheimer's patients.[4]

Hispanics and Latinos in Clinical Research

Hispanic vs Latino in Clinical Research

To properly understand and conduct research on this population, one must recognize the diversity that exists within the Hispanic/Latino community. It is not uncommon to see the terms Latino and Hispanic used interchangeably in formal and informal settings.[46] However, this same attitude is shown in clinical research, as when using the two terms in PubMed and Google Scholar results in a different number of published articles.[3] Nevertheless, these two terms carry vastly different meanings. Hispanic denotes those who can trace their ancestry to a Spanish-speaking country, such as Spain and most of Latin America, the exceptions being Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.[3] On the other hand, the term Latino is used to identify those who can trace their ancestry to Latin America and the Caribbean.[3] Due to the diversity that exists within both groups, many have proposed that the Latino/Hispanic population in the U.S. should not be treated as a monolithic or homogenous group. [6] However, the lack of research on the individual sub-groups has resulted in combining Hispanic/Latino communities as one large group. Recently, researchers are making an effort to clinically represent Hispanics/Latinos based on their country of origin.[6]

The Effect of Socioeconomic status

Many of the factors that prevent the participation of the Hispanic/Latino population in clinical trials tie back to socioeconomic status.[11][6][3] In the U.S., the income and socioeconomic status of Hispanics and Latinos are lower when compared to White Non-Hispanics.[3] It has been reported that 25% of the Hispanic/Latino population lives in poverty and their median family income was $17,800 lower in 2015 than their white counterparts.[3]

| Payment Source | Cost in Billions ($) |

|---|---|

| Medicare | $155 |

| Medicaid | $51 |

| Out of Pocket | $66 |

| Other | $33 |

| TOTAL | $305 |

Moreover, recent data shows that the difference in income is present across many income brackets, as only 38.6% of Latinos reported a household income between $50,000 and $149,999, in comparison to 45.6% of White Non-Hispanics. [3] The low income that is seen in Hispanics and Latinos is also associated with a lower level of education, in terms of higher-level education and medical literacy.[3][6] As of 2013, it was reported that 22% of Latino adults (25 years and over) had earned an associate degree or higher, compared to the 46% seen in White Non-Hispanics.[3] This trend is also seen with advanced degrees, as Latinos only accounted for 7% and 1% of Master and Doctorate degrees awarded in the U.S.[3] The socioeconomic status and education level of this population harm their long-term health—lower levels of education are associated with high mortality and dementia rates.[6][3][11] On the other hand, a high educational level correlated was shown to be neuroprotective and correlated with lower rates of dementia. [4] Lastly, Hispanic and Latinos that are 65 years and older make up one of the largest groups of uninsured individuals in the U.S.[6] This makes it difficult for these seniors, whose age alone already increases their risk of developing Alzheimer's, to see a physician so that they can be diagnosed and treated for Alzheimer's, as well as learn about clinical trials.[4][2][6] Even if these patients had health insurance, the cost of care for patients 65 years and older was estimated to be $25,213 per person, compared to the estimated $7750 for senior patients without AD.[47] Fortunately, many researchers are trying to account for the effects of socioeconomic status by conducting studies in diverse areas, conducting studies in minority communities, and providing travel support for participants.[11][3]

The Language Barrier

In addition to socioeconomic status, there exists a potential language barrier between Healthcare providers and Hispanics and Latinos. Many clinical trials require participants to be fluent in English, which can potentially exclude the older predominantly Spanish-speaking generation.[3][6] Proficiency in English is not an issue in younger Latinos, as 90% of the population between the ages of 5 and 17 speak the language fluently.[3] However, only 40% of the older generation, Latinos over the age of 69, are fluent.[3] Moreover, the language barrier is an issue for one's health. Weak communication between physician and patient leads to a lack of follow-up, unnecessary tests, and misinterpretation of medical advice and dosage instructions.[6][3] This issue is also present in written media, as medical resources and documents written for Spanish-speaking individuals are typically translated from the English version of the same document. [6] By choosing to inform patients of their illnesses in this way, one increases the risk of miscommunication as the diversity within the population also includes the way the Spanish language is spoken. [3][6] Overcoming the language barrier is vital to ensure that Hispanics and Latinos can efficiently engage with their physicians and receive the care they need and deserve. Fortunately, many researchers are looking for ways to overcome this barrier. Methods include recruiting staff and physicians that can communicate with participants in their native language, training researchers and clinicians on cultural sensitivity, providing documents at the appropriate reading level, and using different forms of media (i.e. videos) to overcome the issue of literacy. [3][11]

See also

Race and Health in the United States

References

- ^ a b c Goedert, Michel; Spillantini, Maria Grazia (2006-11-03). "A Century of Alzheimer's Disease". Science. 314 (5800): 777–781. doi:10.1126/science.1132814. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Reitz, Christiane; Rogaeva, Ekaterina; Beecham, Gary W. (2020-10-06). "Late-onset vs nonmendelian early-onset Alzheimer disease". Neurology: Genetics. 6 (5): e512. doi:10.1212/NXG.0000000000000512. ISSN 2376-7839. PMC 7673282. PMID 33225065.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Vega, Irving E.; Cabrera, Laura Y.; Wygant, Cassandra M.; Velez-Ortiz, Daniel; Counts, Scott E. (2017-06-23). Abisambra, Jose (ed.). "Alzheimer's Disease in the Latino Community: Intersection of Genetics and Social Determinants of Health". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 58 (4): 979–992. doi:10.3233/JAD-161261. PMC 5874398. PMID 28527211.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Breijyeh, Zeinab; Karaman, Rafik (2020-12-08). "Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer's Disease: Causes and Treatment". Molecules. 25 (24): 5789. doi:10.3390/molecules25245789. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 7764106. PMID 33302541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tosto, Giuseppe; Reitz, Christiane (2016-12-01). "Genomics of Alzheimer's disease: Value of high-throughput genomic technologies to dissect its etiology". Molecular and Cellular Probes. Genetics of multifactorial diseases. 30 (6): 397–403. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2016.09.001. ISSN 0890-8508.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Massett, Holly A.; Mitchell, Alexandra K.; Alley, Leah; Simoneau, Elizabeth; Burke, Panne; Han, Sae H.; Gallop-Goodman, Gerda; McGowan, Melissa (2021-06-29). Gleason, Carey (ed.). "Facilitators, Challenges, and Messaging Strategies for Hispanic/Latino Populations Participating in Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias Clinical Research: A Literature Review". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 82 (1): 107–127. doi:10.3233/JAD-201463.

- ^ Marquez, David X.; Perez, Adriana; Johnson, Julene K.; Jaldin, Michelle; Pinto, Juan; Keiser, Sahru; Tran, Thi; Martinez, Paula; Guerrero, Javier; Portacolone, Elena (26 July 2022). "Increasing engagement of Hispanics/Latinos in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias". Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 8 (1). doi:10.1002/trc2.12331. ISSN 2352-8737. PMC 9322823. PMID 35910673.

- ^ a b c Liu, Chia-Chen; Kanekiyo, Takahisa; Xu, Huaxi; Bu, Guojun (February 2013). "Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms, and therapy". Nature reviews. Neurology. 9 (2): 106–118. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. ISSN 1759-4758. PMC 3726719. PMID 23296339.

- ^ Nazha, Bassel; Mishra, Manoj; Pentz, Rebecca; Owonikoko, Taofeek K. (2019-05-01). "Enrollment of Racial Minorities in Clinical Trials: Old Problem Assumes New Urgency in the Age of Immunotherapy". American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book (39): 3–10. doi:10.1200/EDBK_100021. ISSN 1548-8748.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bekris, Lynn M.; Yu, Chang-En; Bird, Thomas D.; Tsuang, Debby W. (24 February 2011). "Genetics of Alzheimer Disease". Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 23 (4): 213–227. doi:10.1177/0891988710383571. ISSN 0891-9887. PMC 3044597. PMID 21045163.

- ^ a b c d e f g Konkel, Lindsey (1 December 2015). "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Research Studies: The Challenge of Creating More Diverse Cohorts". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (12): A297–A302. doi:10.1289/ehp.123-A297. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 4670264. PMID 26625444.

- ^ a b c d Piaceri, Irene; Nacmias, Benedetta; Sorbi, Sandro (2013-01-01). "Genetics of familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease". Frontiers in Bioscience-Elite. 5 (1): 167–177. doi:10.2741/E605. ISSN 1945-0494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sun, Qiying; Xie, Nina; Tang, Beisha; Li, Rena; Shen, Yong (2017). "Alzheimer's Disease: From Genetic Variants to the Distinct Pathological Mechanisms". Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 10. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2017.00319/full. ISSN 1662-5099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Huynh, Rose Ann; Mohan, Chandra (2017). "Alzheimer's Disease: Biomarkers in the Genome, Blood, and Cerebrospinal Fluid". Frontiers in Neurology. 8. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00102/full. ISSN 1664-2295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e "What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer's Disease?". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Tan, Meng-Shan; Yu, Jin-Tai; Tan, Lan (2013-10-01). "Bridging integrator 1 (BIN1): form, function, and Alzheimer's disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 19 (10): 594–603. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2013.06.004. ISSN 1471-4914.

- ^ a b c Leng, Fangda; Edison, Paul (2021-03). "Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here?". Nature Reviews Neurology. 17 (3): 157–172. doi:10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y. ISSN 1759-4766.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rohn, Troy T. (2013-03-06). "The Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2: "TREM-ming" the Inflammatory Component Associated with Alzheimer's Disease". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013: e860959. doi:10.1155/2013/860959. ISSN 1942-0900.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Baldacci, Filippo; Lista, Simone; Palermo, Giovanni; Giorgi, Filippo Sean; Vergallo, Andrea; Hampel, Harald (2019-07-03). "The neuroinflammatory biomarker YKL-40 for neurodegenerative diseases: advances in development". Expert Review of Proteomics. 16 (7): 593–600. doi:10.1080/14789450.2019.1628643. ISSN 1478-9450.

- ^ Li, Lanlan; Yu, Xianfeng; Sheng, Can; Jiang, Xueyan; Zhang, Qi; Han, Ying; Jiang, Jiehui (2022-09-15). "A review of brain imaging biomarker genomics in Alzheimer's disease: implementation and perspectives". Translational Neurodegeneration. 11 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/s40035-022-00315-z. ISSN 2047-9158. PMC 9476275. PMID 36109823.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Langa, Kenneth M.; Levine, Deborah A. (2014-12-17). "The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review". JAMA. 312 (23): 2551–2561. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13806. ISSN 1538-3598. PMC 4269302. PMID 25514304.

- ^ a b c Briceño, Emily M.; Mehdipanah, Roshanak; Gonzales, Xavier Fonz; Langa, Kenneth M.; Levine, Deborah A.; Garcia, Nelda M.; Longoria, Ruth; Giordani, Bruno J.; Heeringa, Steven G.; Morgenstern, Lewis B. (13 April 2020). "Neuropsychological assessment of mild cognitive impairment in Latinx adults: A scoping review". Neuropsychology. 34 (5): 493–510. doi:10.1037/neu0000628. ISSN 1931-1559. PMC 8209654. PMID 32281811.

- ^ a b c Briceño, E; Mehdipanah, R; Gonzales, X; Langa, K; Levine, D; Garcia, N; Longoria, R; Giordani, B; Heeringa, S; Morgenstern, L (2019-08-30). "Culture and Diagnosis of MCI in Hispanics: A Literature Review". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 34 (7): 1239–1239. doi:10.1093/arclin/acz029.06. ISSN 1873-5843.

- ^ González, Hector M.; Tarraf, Wassim; Fornage, Myriam; González, Kevin A.; Chai, Albert; Youngblood, Marston; Abreu, Maria de los Angeles; Zeng, Donglin; Thomas, Sonia; Talavera, Gregory A.; Gallo, Linda C.; Kaplan, Robert; Daviglus, Martha L.; Schneiderman, Neil (2019-12-01). "A research framework for cognitive aging and Alzheimer's disease among diverse US Latinos: Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos—Investigation of Neurocognitive Aging (SOL-INCA)". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 15 (12): 1624–1632. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.08.192. ISSN 1552-5260.

- ^ Arévalo, Sandra P.; Kress, Jennifer; Rodriguez, Francisca S. (April 2020). "Validity of Cognitive Assessment Tools for Older Adult Hispanics: A Systematic Review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 68 (4): 882–888. doi:10.1111/jgs.16300. ISSN 1532-5415. PMID 31886524.

- ^ a b "How Biomarkers Help Diagnose Dementia". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ Huynh, Rose Ann; Mohan, Chandra (2017). "Alzheimer's Disease: Biomarkers in the Genome, Blood, and Cerebrospinal Fluid". Frontiers in Neurology. 8. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00102/full. ISSN 1664-2295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Yin, Rui-Hua; Yu, Jin-Tai; Tan, Lan (2015-06-01). "The Role of SORL1 in Alzheimer's Disease". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (3): 909–918. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8742-5. ISSN 1559-1182.

- ^ a b KHANAHMADI, Mohammad; FARHUD, Dariush D.; MALMIR, Maryam (July 2015). "Genetic of Alzheimer's Disease: A Narrative Review Article". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 44 (7): 892–901. ISSN 2251-6085. PMC 4645760. PMID 26576367.

- ^ Jiang, Haowei; Jayadev, Suman; Lardelli, Michael; Newman, Morgan (2018-01-01). "A Review of the Familial Alzheimer's Disease Locus PRESENILIN 2 and Its Relationship to PRESENILIN 1". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 66 (4): 1323–1339. doi:10.3233/JAD-180656. ISSN 1387-2877.

- ^ Tejada-Vera B. (2013). Mortality from Alzheimer's Disease in the United States: Data for 2000 and 2010. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ^ a b c d Vardarajan, Badri N.; Zhang, Yalun; Lee, Joseph H.; Cheng, Rong; Bohm, Christopher; Ghani, Mahdi; Reitz, Christiane; Reyes-Dumeyer, Dolly; Shen, Yufeng; Rogaeva, Ekaterina; St George-Hyslop, Peter; Mayeux, Richard (7 November 2014). "Coding mutations in SORL 1 and Alzheimer disease: SORL1 Variants and AD". Annals of Neurology. 77 (2): 215–227. doi:10.1002/ana.24305. PMC 4367199. PMID 25382023.

- ^ Stieger, Bruno (2007-01-01), Enna, S. J.; Bylund, David B. (eds.), "ABC1, ATP Binding Cassette Permease 1", xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference, New York: Elsevier, pp. 1–3, ISBN 978-0-08-055232-3, retrieved 2022-12-03

- ^ a b Dib, Shiraz; Pahnke, Jens; Gosselet, Fabien (27 April 2021). "Role of ABCA7 in Human Health and in Alzheimer's Disease". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (9): 4603. doi:10.3390/ijms22094603. ISSN 1422-0067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e Foster, Evangeline M.; Dangla-Valls, Adrià; Lovestone, Simon; Ribe, Elena M.; Buckley, Noel J. (2019). "Clusterin in Alzheimer's Disease: Mechanisms, Genetics, and Lessons From Other Pathologies". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 13. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00164/full. ISSN 1662-453X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Du, Wenjin; Tan, Jiping; Xu, Wei; Chen, Jinwen; Wang, Luning (2016-11-01). "Association between clusterin gene polymorphism rs11136000 and late‑onset Alzheimer's disease susceptibility: A review and meta‑analysis of case‑control studies". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 12 (5): 2915–2927. doi:10.3892/etm.2016.3734. ISSN 1792-0981. PMC 5103725. PMID 27882096.

- ^ a b c d e Santiago, Jose A.; Potashkin, Judith A. (2021-02-12). "The Impact of Disease Comorbidities in Alzheimer's Disease". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 13: 631770. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.631770. ISSN 1663-4365. PMC 7906983. PMID 33643025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Oparil, Suzanne; Acelajado, Maria Czarina; Bakris, George L.; Berlowitz, Dan R.; Cífková, Renata; Dominiczak, Anna F.; Grassi, Guido; Jordan, Jens; Poulter, Neil R.; Rodgers, Anthony; Whelton, Paul K. (2018-03-22). "Hypertension". Nature reviews. Disease primers. 4: 18014. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2018.14. ISSN 2056-676X. PMC 6477925. PMID 29565029.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mills, Katherine T; Stefanescu, Andrei; He, Jiang (April 2020). "The global epidemiology of hypertension". Nature reviews. Nephrology. 16 (4): 223–237. doi:10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2. ISSN 1759-5061. PMC 7998524. PMID 32024986.

- ^ a b c Guzman, Nicolas J. (2012-06-01). "Epidemiology and Management of Hypertension in the Hispanic Population". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 12 (3): 165–178. doi:10.2165/11631520-000000000-00000. ISSN 1179-187X. PMC 3624012. PMID 22583147.

- ^ a b c Galicia-Garcia, Unai; Benito-Vicente, Asier; Jebari, Shifa; Larrea-Sebal, Asier; Siddiqi, Haziq; Uribe, Kepa B.; Ostolaza, Helena; Martín, César (30 August 2020). "Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (17): 6275. doi:10.3390/ijms21176275. ISSN 1422-0067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Olokoba, Abdulfatai B.; Obateru, Olusegun A.; Olokoba, Lateefat B. (July 2012). "Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Current Trends". Oman Medical Journal. 27 (4): 269–273. doi:10.5001/omj.2012.68. ISSN 1999-768X. PMC 3464757. PMID 23071876.

- ^ a b c d e f Avilés-Santa, M. Larissa; Colón-Ramos, Uriyoán; Lindberg, Nangel M.; Mattei, Josiemer; Pasquel, Francisco J.; Pérez, Cynthia M. (2017). "From Sea to Shining Sea and the Great Plains to Patagonia: A Review on Current Knowledge of Diabetes Mellitus in Hispanics/Latinos in the US and Latin America". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 8. doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00298/full. ISSN 1664-2392.