Low back pain: Difference between revisions

imaging - add crownover 2013 |

diff diag - add henschke 2013 |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

===Differential diagnosis=== |

===Differential diagnosis=== |

||

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from [[radiculopathy]] and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using [[diagnostic imaging]] or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem. With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain typically are treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the underlying cause.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> |

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from [[radiculopathy]] and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using [[diagnostic imaging]] or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> In addition, the successful finding of some red flags comes with a high risk of a false-positive diagnosis of spinal malignancy; study evidence does not recommend their use, especially for making a diagnosis based on the presence of only one red flag.<ref name=henschke_2013> With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain typically are treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the underlying cause.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> |

||

===Imaging=== |

===Imaging=== |

||

| Line 254: | Line 254: | ||

<ref name=henschke_2009>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, ''et al.'' |title=Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=60 |issue=10 |pages=3072–80 |year=2009 |month=October |pmid=19790051 |doi=10.1002/art.24853 |url=}}</ref> |

<ref name=henschke_2009>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, ''et al.'' |title=Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=60 |issue=10 |pages=3072–80 |year=2009 |month=October |pmid=19790051 |doi=10.1002/art.24853 |url=}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=henschke_2013>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L |title=Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=2 |issue= |pages=CD008686 |year=2013 |pmid=23450586 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008686.pub2 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=hoy_2012>{{cite journal |author=Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, ''et al.'' |title=A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=2028–37 |year=2012 |month=June |pmid=22231424 |doi=10.1002/art.34347 |url=}}</ref> |

<ref name=hoy_2012>{{cite journal |author=Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, ''et al.'' |title=A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=2028–37 |year=2012 |month=June |pmid=22231424 |doi=10.1002/art.34347 |url=}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:34, 4 June 2013

| Low back pain | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery, rehabilitation |

Low back pain or lumbago /lʌmˈbeɪɡoʊ/ is a common musculoskeletal disorder affecting 80% of people at some point in their lives. In the United States it is the most common cause of job-related disability, a leading contributor to missed work, and the second most common neurological ailment — only headache is more common.[1] It can be either acute, subacute or chronic in duration. With conservative measures, the symptoms of low back pain typically show significant improvement within a few weeks from onset.

Classification

Lower back pain may be classified by the duration of symptoms as acute, subacute and chronic. Within these classifications, there is no agreement across medical organizations for the specific duration of symptoms, but generally pain lasting less than six weeks is classified as acute, pain lasting six to 12 weeks is subacute, and more than 12 weeks is chronic.[2]

Cause

The majority of lower back pain is referred to as non specific low back pain and does not have a definitive cause.[3] It is believed to stem from benign musculoskeletal problems such as muscle or soft tissues sprain or strains.[1] This is particularly true when the pain arose suddenly during physical loading of the back, with the pain lateral to the spine. Over 99% of back pain instances fall within this category.[4] The full differential diagnosis includes many other less common conditions.

- Mechanical:

- Apophyseal osteoarthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Degenerative discs

- Scheuermann's kyphosis

- Spinal disc herniation ("slipped disc")

- Thoracic or lumbar spinal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis and other congenital abnormalities

- Fractures

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- Unequal leg length

- Restricted hip motion

- Misaligned pelvis - pelvic obliquity, anteversion or retroversion Template:Nb10

- Abnormal foot pronation

- Inflammatory:

- Seronegative spondylarthritides (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Infection - epidural abscess or osteomyelitis

- Sacroiliitis

- Neoplastic:

- Bone tumors (primary or metastatic)

- Intradural spinal tumors

- Metabolic:

- Osteoporotic fractures

- Osteomalacia

- Ochronosis

- Chondrocalcinosis

- Psychosomatic

- Paget's disease

- Referred pain:

- Pelvic/abdominal disease

- Prostate Cancer

- Posture

- Oxygen deprivation

Pathophysiology

Sensation

In general, pain is an unpleasant feeling in response to stimuli that have the potential to damage or do damage the body's tissues (noxious stimuli). There are four fundamental steps in the process of pain perception: transduction, transmission, perception and modulation. The process starts when the potentially pain-causing event stimulates the endings of specialized nerve cells (nociceptors). A nociceptor converts the stimulus into an electrical signal by transduction. Several different types of nerve fibers carry out the transmission of the electrical signal from the transducing nociceptor to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, from there to the brain stem, and then from the brain stem to the various parts of the brain such as the thalamus and the limbic system. There, the pain signals are processed and given context in the process of pain perception. Through modulation, the brain can then modify the sending of further nerve impulses by signaling the release of neurotransmitters that either inhibit them (for example, serotonin and endorphins) or stimulate them.[5]

Afferent nerve fibers carry nerve impulses from sensory nerve cells in the lower back towards the central nervous system.[6] Signals travel to the dorsal root ganglia (the connections between the peripheral nerves and the central spinal nerves) along three types of afferent nerve fibers: A beta fibers, A delta fibers, and C fibers.[5] The fibers of the A group are coated to differing degrees with myelin,[5] an electrical insulator that prevents signal loss and increases transmission speed.[7] The A beta fibers transmit light touch and not pain messages, and as they are heavily myelinated, they transfer their signals quickly. The A delta and C fibers handle pain messages, and as they are less myelinated, they transfer their signals more slowly.[5] These nerve cells release certain chemicals (peptides) in response to painful stimuli.[5]

The afferent nerves, carrying all types of sensation, terminate at the multi-layered dorsal horn of the spinal cord.[5] Generally, the different layers carry different types of sensation so that, for example, the layers carrying pain signals are separate from the layers carrying touch signals.[5] The signals then travel from the dorsal horn to the brain.[5] In the brain, the signals interact with the limbic system.[5]

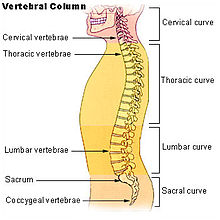

Back structures

The lumbar region (or lower back region) is made up of five vertebrae (L1-L5). In between these vertebrae lie fibrocartilage discs (intervertebral discs), which act as cushions, preventing the vertebrae from rubbing together while at the same time protecting the spinal cord. Nerves stem from the spinal cord through foramina within the vertebrae, providing muscles with sensations and motor associated messages. Stability of the spine is provided through ligaments and muscles of the back, lower back and abdomen. Small joints which prevent, as well as direct, motion of the spine are called facet joints (zygapophysial joints).[8]

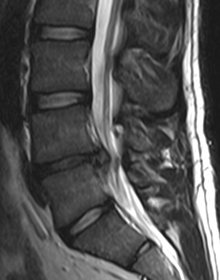

Causes of lower back pain are varied. Most cases are believed to be due to a sprain or strain in the muscles and soft tissues of the back.[1] Overactivity of the muscles of the back can lead to an injured or torn ligament in the back which in turn leads to pain. An injury can also occur to one of the intervertebral discs (disc tear, disc herniation). Due to aging, discs begin to diminish and shrink in size, resulting in vertebrae and facet joints rubbing against one another. Ligament and joint functionality also diminishes as one ages, leading to spondylolisthesis, which causes the vertebrae to move much more than they should. Pain is also generated through lumbar spinal stenosis, sciatica and scoliosis. At the lowest end of the spine, some patients may have tailbone pain (also called coccyx pain or coccydynia). Others may have pain from their sacroiliac joint, where the spinal column attaches to the pelvis, called sacroiliac joint dysfunction which may be responsible for 22.6% of low back pain.[9] Physical causes may include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, degeneration of the discs between the vertebrae or a spinal disc herniation, a vertebral fracture (such as from osteoporosis), or rarely, an infection or tumor.[10]

In the vast majority of cases, no noteworthy or serious cause is ever identified. If the pain resolves after a few weeks, intensive testing is not indicated.[11][unreliable source]

Diagnostic approach

| Red flags[12] |

|---|

| Recent significant trauma |

| Milder trauma if age > 50 |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| Unexplained fever |

| Immunosuppression |

| History of cancer |

| Intravenous drug use |

| Osteoporosis |

| Chronic corticosteroid use |

| Age > 70 years |

| Focal neurological deficit |

| Duration > 6 weeks |

Differential diagnosis

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from radiculopathy and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using diagnostic imaging or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem.[2][3] In addition, the successful finding of some red flags comes with a high risk of a false-positive diagnosis of spinal malignancy; study evidence does not recommend their use, especially for making a diagnosis based on the presence of only one red flag.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

It is most common among women, and among people aged 40–80 years, with the overall number of individuals affected expected to increase as the population ages. Women may be more prone to raise the complaint due to pain related to osteoporosis, menstruation or pregnancy, or it may be that women are more willing than men to report pain due to differences in social expectations between the two groups. Prevalence is elevated among adolescents, with females reporting it earlier than males, possibly showing a correlation between low back pain and the onset of puberty, as females enter puberty earlier than males.[13] Of American adults, 26% report pain of at least one day in duration every three months.[14]

History

Low back pain has been with humans since at least the Bronze Age. The oldest known surgical treatise - the Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to about 1500 BCE - describes a diagnostic test and treatment for a physician to use on encountering a vertebral sprain. Hippocrates (c. 460 BCE – c. 370 BCE) was the first to make use of terms for sciatic pain and low back pain; Galen (active mid to late second century CE) detailed the concepts. Physicians through the end of the first millennium did not attempt back surgery of any kind, and recommended only watchful waiting. Through the Medieval period, folk medicine practitioners provided treatments for back pain based on the belief that it was caused by spirits.[15]

By the start of the 20th century, physicians thought low back pain was simply caused by inflammation of or damage to the nerves,[15] with neuralgia and neuritis frequently cited;[16] the popularity of such proposed neural main etiologies declined steadily throughout the century.[16] In the 1920s and 30s, new theories for the cause of low pack pain arose, with physicians proposing a combination of nervous system and psychological disorders such as neurasthenia, hysteria, or psychogenesis.[15] Muscular causes such as "muscular rheumatism" (now called fibromyalgia) were cited with increasing frequency as well.[16]

Emerging technologies such as radiography gave physicians new diagnostic tools, which revealed the intervertebral disk as a source for back pain. In 1938, orthopedic surgeon Joseph S. Barr reported on cases of disk-related sciatica improved or cured with back surgery;[16] consequently, in the 1940s, the vertebral disk model of low back pain took over,[15] dominating the literature through the 1980s, especially after the rise of new imaging technologies such as CT and MRI.[16] Such discussion later subsided as further research showed that it was actually relatively uncommon for disk problems to be the source of the pain, but even with the knowledge that diagnostic tools could show abnormalities probably unrelated to the patient's pain, physicians would still look to the tools' results instead of physical examinations for diagnosis and treatment plans. Since then, physicians have come to question whether it is likely that they will be able to identify a specific cause for a complaint of low back pain, or whether finding one is even necessary, as most complaints resolve themselves within six to 12 week regardless of treatment.[15]

Economics

In the United States, estimates of the costs of low back pain range between $38 and $50 billion a year and there are 300,000 operations annually. Back and neck operations are the third most common form of surgery in the United States.[17] Between 1990 and 2001 there was a 220% increase in spinal fussions in the United States, despite the fact that during that period there were no changes, clarifications, or improvements in the indications for surgery or new evidence of improved effectiveness.[18]

Women

Women may experience acute low back pain due to certain medical conditions of the female reproductive system, including endometriosis, ovarian cysts, ovarian cancer, or uterine fibroids.[19]

An estimated 50-70% of pregnant women experience back pain.[20] As one gets farther along in the pregnancy, due to the additional weight of the fetus, one’s center of gravity will shift forward causing one’s posture to change. This change in posture leads to increasing lower back pain.[20][21]

References

- ^ a b c "Lower Back Pain Fact Sheet. nih.gov". Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ a b Koes, BW (2010 Dec). "An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care". European Spine Journal. 19 (12): 2075–94. PMID 20602122.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Casazza, BA (2012 Feb 15). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain". American family physician. 85 (4): 343–50. PMID 22335313.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM; et al. (2009). "Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain". Arthritis Rheum. 60 (10): 3072–80. doi:10.1002/art.24853. PMID 19790051.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Salzberg L (2012). "The physiology of low back pain". Prim. Care. 39 (3): 487–98. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.014. PMID 22958558.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Physiology of Behavior (11 ed.). 2012. ISBN 978-0205239399.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Hartline DK (2008). "What is myelin?". Neuron Glia Biol. 4 (2): 153–63. doi:10.1017/S1740925X09990263. PMID 19737435.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Floyd, R., & Thompson, Clem. (2008). Manual of structural kinesiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

- ^ T N Bernard and W H Kirkaldy-Willis, "Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain," Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, no. 217 (April 1987) 266-280.

- ^ Burke,G.L.,MD, (1964). Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx. Vancouver, BC: Macdonald Publishing.

- ^ Atlas SJ (2010). "Nonpharmacological treatment for low back pain". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (1): 20–27.[unreliable source]

- ^ "American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria - Low Back Pain" (PDF). American College of Radiology.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G; et al. (2012). "A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain". Arthritis Rheum. 64 (6): 2028–37. doi:10.1002/art.34347. PMID 22231424.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Deyo, Richard A.; Mirza, Sohail K.; Martin, Brook I. (2006). "Back Pain Prevalence and Visit Rates". Spine. 31 (23): 2724–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. PMID 17077742.

- ^ a b c d e Maharty DC (2012). "The history of lower back pain: a look "back" through the centuries". Prim. Care. 39 (3): 463–70. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.002. PMID 22958555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Lutz GK, Butzlaff M, Schultz-Venrath U (2003). "Looking back on back pain: trial and error of diagnoses in the 20th century". Spine. 28 (16): 1899–905. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000083365.41261.CF. PMID 12923482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ACSM's Resources for Clinical Exercise Physiology: Musculoskeletal, Neuromuscular, Neoplastic, Immunologic and Hematologic Conditions (2 ed.). 2009. p. 149. ISBN 978-0781768702.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Deyo, RA; Mirza, SK; Turner, JA; Martin, BI (2009). "Overtreating Chronic Back Pain: Time to Back Off?". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 22 (1): 62–8. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080102. PMC 2729142. PMID 19124635.

- ^ "Low back pain - acute". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b Danforth Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, 2003, James. Gibbs, et al, Ch. 1

- ^ Williams Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, 2005, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 8,

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "AAOS_2009" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "AHRQ_2012" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "bestbets_3" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "choi_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "chou_2007" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "chou_2009_imaging" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "chou_2009_rehab" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "chou_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "chou_2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "crownover_2013" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "dagenais_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "dagenais_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "delavier_2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "deshpande_2007" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "dubinsky_2009" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "ernst_2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "french_2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "furlan_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "garra_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "haake_2007" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "hayden_2005" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "henschke_2013" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "king_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "koes_2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "kovacs_2003" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "machado_2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "malanga_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "manusov_2012" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "mayo" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "menezes_2012" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "middelkoop_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "middelkoop_2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "mirza_2007" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "pinto_2012" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "roelofs_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "rubinstein_2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "rubinstein_2012" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "smith_2010" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "spineuniverse" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "urquhart_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "van_duijvenbode_2008" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "vantulder_2006" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "walker_2011" is not used in the content (see the help page).

External links

- Back and spine at Curlie

- Upper Back Pain Article on UpperBackPains.net