Echinostoma: Difference between revisions

Category:Parasitic animals |

Significant update of article. Taxonomy, morphology, geographic distribution, life cycle, echinostomiasis, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prevention, references and images added |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Echinostoma''' is a [[genus]] of [[trematoda|trematode]] parasites, which can infect both humans and [[animal|animals]]. These intestinal [[trematoda|flukes]] have a three-host life cycle with [[snails]] or aquatic organisms as [[intermediate hosts]], and a variety of animals, including humans, as their [[host (biology)|definitive hosts]]. |

|||

''Echinostoma'' infect the [[human gastrointestinal tract|gastrointestinal tract]] of humans, and can cause a disease known as echinostomiasis. The parasites are spread when humans or animals eat infected raw or undercooked food, such as [[bivalvia|bivalve molluscs]] or [[fish]] <ref name="Toledo2012" /> |

|||

{{Italic title}}{{Taxobox |

{{Italic title}}{{Taxobox |

||

| name = ''Echinostoma'' |

| name = ''Echinostoma'' |

||

| image = Echinostoma revolutum.png |

| image = Echinostoma revolutum.png |

||

| image_caption = |

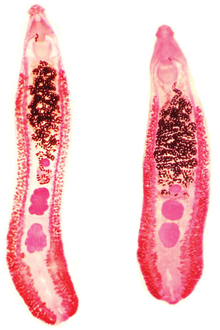

| image_caption = Two specimens of ''[[Echinostoma revolutum]]'' |

||

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

||

| phylum = [[Flatworm|Platyhelminthes]] |

| phylum = [[Flatworm|Platyhelminthes]] |

||

| Line 11: | Line 15: | ||

| genus = '''''Echinostoma''''' |

| genus = '''''Echinostoma''''' |

||

| genus_authority = [[Karl Rudolphi|Rudolphi]], 1809<ref>[[Karl Rudolphi|Rudolphi K.]] (1809). ''Entoz. Hist. Nat.'' '''2'''(1): 38.</ref> |

| genus_authority = [[Karl Rudolphi|Rudolphi]], 1809<ref>[[Karl Rudolphi|Rudolphi K.]] (1809). ''Entoz. Hist. Nat.'' '''2'''(1): 38.</ref> |

||

| subdivision_ranks = [[Species]] |

|||

| subdivision = |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma caproni]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma echinatum]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma friedi]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma hortense]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma ilocanum]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma jurini]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma luisyrei]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma miyagawai]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma paraensei]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma parvocirris]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma revolutum]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Echinostoma trivolvis]]'' |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Echinostoma''''' is an important [[genus]] that includes many [[parasitism|parasites]]. |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

Human [[echinostomiasis]] is an intestinal parasitic disease caused by one of at least sixteen trematode flukes from the genus ''Echinostoma''. Found largely in southeast [[Asia]] and the Far East, mainly in cosmopolitan areas. It has extensive [[vitelline gland]]s for egg yolk production and tandem, oval testes. Echinostomiasis is transmitted through the ingestion of one of several possible intermediate hosts, which could include [[snail]]s or other [[mollusk]]s, certain freshwater fish, [[crustacean]]s or [[amphibian]]s. These flukes are of moderate size, about 2 mm, and are distinguished by an oral sucker surrounded by a characteristic collar of spines. |

|||

It has been estimated that there are between 61 and 114 species of ''Echinostoma''.<ref name="AinP" /> ''Echinostoma'' are difficult to [[biological classification|classify]] and are known as a [[cryptic species complex|cryptic species]] (different lineages are considered to be the same species, due to high morphological similarity between them).<ref name="Detwiler2010">{{Cite journal | author=Detwiler JT, Bos DH & Minchella DJ | title= Revealing the secret lives of cryptic species: Examining the phylogenetic relationships of echinostome parasites in North America | journal=[[Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution]] | volume=55 | year=2010 | pages=611-620 | doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.004}} </ref> Many [[species]] of ''Echinostoma'' have been re-classified several times. For example, the species now known as ''Echinostoma caproni'', was previously known by a variety of names including ''E. liei'', ''E. parasensei'' and ''E. togoensis''.<ref name="AinP">{{cite book |last1=Huffman|first1=Jane E|last2=Fried|first2=Bernard|editor1-first=John R|editor1-last=Baker|editor2-first=Ralph|editor2-last=Muller|title=Advances in Parasitology|publisher=Academic Press Limited|date= 1990|pages=215-269 |chapter=Echinostoma and Echinostomiasis |isbn=0-12-031729-X}}</ref> |

|||

Methods for classifying ''Echinostoma'' species, such as the ''[[Echinostoma revolutum]]'' group, were devised by Kanev.<ref name="Kanev1994">{{Cite journal | author=Kanev I | title= Life-cycle, delimitation and redescription of ''Echinostoma revolutum'' (Froelich, 1802) (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae)| journal=[[Systematic Parasitology]] | volume=28 | year=1994 | pages=125-144 | doi=10.1007/BF00009591}} </ref> The ''Echinostoma'' species in this group are now classified according to their shared [[morphology|morphological]] and biological characteristics, such as the presence of 37 collar spines.<ref name="Kanev1994" /> |

|||

Adults are in the small [[intestine]]s of vertebrate definitive hosts. Eggs are released through the feces and embryonated. The egg becomes a [[miracidium]] with an operculum, which penetrates a snail, the first [[intermediate host]]. Upon penetration, it becomes a mother [[Trematode lifecycle stages|sporocyst]], producing many mother [[rediae]]. Each of these mother redia produce many daughter rediae, which each produce many free-swimming [[cercariae]]. Each of these cercaria encysts in a freshwater mollusc, the second intermediate host, becoming a [[metacercaria]]. These mollusc are eaten by a vertebrate, the definitive host. |

|||

Molecular methods, such as sequencing [[mitochondrial DNA]] and [[ribosomal DNA]], are also used to distinguish between species of ''Echinostoma'' as an alternative to morphological classification methods.<ref>{{Cite journal | author=Morgan JAT & Blair D | title= Relative merits of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacers and mitochondrial CO1 and ND1 genes for distinguishing among ''Echinostoma'' species (Trematoda)| journal=[[Parasitology]] | volume=116 | year=1998 | pages=289-297}} </ref> |

|||

Upon infection of the human [[Host (biology)|host]], the worms aggregate in the small intestine where they may cause no symptoms, mild symptoms, or severe symptoms in rare cases, depending on the number of worms present. [[Diarrhea]] is a result of heavy infections. Effective drugs for treatment do exist, but the disease still remains a problem in endemic areas. |

|||

==Morphology== |

|||

Prevention and control is possible through measures such as [[health education]]; altered eating habits to exclude ingestion of raw fish, mollusks and other sources of the disease; and removing of [[wastewater]] and industrial discharge that may be home to the parasite. |

|||

''Echinostoma'' are internal [[digenea|digenean]] [[Trematoda|trematode]] parasites which infect the intestines and [[bile duct]]<ref name="AinP" /> of their [[Host (biology)|hosts]]. |

|||

The length and width of adult ''Echinostoma'' varies between species, but they tend to be approximately 2-10mm x 1-2mm in size.<ref name="CDC1">{{cite web|last=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|title=Echinostomiasis|url= http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinostomiasis/gallery.html#adults |archiveurl= http://www.webcitation.org/6OACP5ekP |archivedate=18 March 2014}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[List of parasites (human)]] |

|||

Adult ''Echinostoma'' have two [[sucker (zoology)|suckers]]: an anterior oral sucker and a ventral sucker.<ref name="AinP" /> They also have a characteristic head collar with spines surrounding their oral [[sucker (zoology)|sucker]].<ref name="Gonçalves2013"> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Cite journal | author=Gonçalves JP, Oliveira-Menezes A, Maldonado Junior A et al | title= Evaluation of Praziquantel effects on |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

''Echinostoma paraensei'' ultrastructure | journal=[[Veterinary Parasitology]] | volume=194 | year=2013 | pages=16-25 | doi=10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.042}} </ref> The number of collar spines varies between ''Echinostoma'' species, but there are usually between 27 and 51.<ref name="AinP" /> These spines can be arranged in one or two circles around the [[sucker (zoology)|sucker]], and their arrangement may be a characteristic feature of an ''Echinostoma'' species.<ref name="AinP" /> |

|||

''Echinostoma'' have a digestive system consisting of a [[pharynx]], [[esophagus|oesophagus]] and an excretory pore.<ref name="AinP" /> |

|||

[[Category:Digenea]] |

|||

[[Category:Parasitic animals]] |

|||

''Echinostoma'' are [[hermaphrodite|hermaphrodites]],<ref name="Gonçalves2013" /> and have both male and female reproductive organs. The [[testicle|testes]] are found in the posterior part of the fluke’s body, in the area furthest from the [[mouth]].<ref name="AinP" /> The [[ovary]] is also found in this location, close to the testes.<ref name="AinP" /> |

|||

{{Parasite-stub}} |

|||

The [[egg|eggs]] (ova) of ''Echinostoma'' are operculate <ref name="AinP" /> and vary in size, but are typically in the range of 80-135μm x 55-80μm.<ref>{{cite web|title=Echinostomiasis|url=http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinostomiasis/gallery.html#eggs|author=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6OACmeBBN|archivedate=18 March 2014|date=29 November 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Geographic Distribution== |

|||

The [[genus]] ''Echinostoma'' has a global [[species distribution|distribution]]. These parasites are particularly common in South East Asia, in countries such as [[South Korea]] and the [[Philippines]].<ref name="Furst2012"> |

|||

{{Cite journal | author=Fürst T, Keiser J & Utzinger A | title= Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal=[[The Lancet Infectious Diseases]] | volume=12 | year=2012 | pages=210-221| doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70294-8}} </ref> However, they are also found in some European countries,<ref name="Kanev1994">{{Cite journal | author=Kanev I | title= Life-cycle, delimitation and redescription of ''Echinostoma revolutum'' (Froelich, 1802) (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae)| journal=[[Systematic Parasitology]] | volume=28 | year=1994 | pages=125-144| doi=10.1007/BF00009591}} </ref> and species such as ''Echinostoma trivolvis'' are found in [[North America]].<ref name="Kanev1995"> {{Cite journal | author=Kanev I, Fried B, Dimitrov V & Radev V | title= Redescription of ''Echinostoma trivolvis'' (Cort, 1914) (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) with a discussion on its identity | journal=[[Systematic Parasitology]] | volume=32 | year=1995 | pages=61-70| doi=10.1007/BF00009468}} </ref> |

|||

==Life Cycle== |

|||

''Echinostoma'' have three [[host (biology)|hosts]] in their [[Biological life cycle|life cycle]]: a first [[intermediate host]], a second intermediate host and a [[host (biology)|definitive host]]. [[Snails|Snail]] species such as ''[[Lymnaea]]'' spp. are common intermediate hosts for ''Echinostoma'',<ref name="AinP" /> although [[fish]] and other [[Bivalvia|bivalve molluscs]] can be also be intermediate hosts for these parasites. <ref name="CDC Index">{{cite web|title=Echinostomiasis|url=http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinostomiasis/index.html|author=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6OACsim37|archivedate=18 March 2014|date=29 November 2013}}</ref> |

|||

''Echinostoma'' species have low specificity for their definitive [[host (biology)|hosts]], and can [[infection|infect]] a variety of different [[species]] of [[animal]], including [[Amphibian|amphibians]],<ref name="Belden2006">{{Cite journal | author=Belden LK | title= Impact of eutrophication on wood frog, ''Rana sylvatica'', tadpoles infected with ''Echinostoma trivolvis'' cercariae| journal=[[Canadian Journal of Zoology]] | volume=84 | year=2006| pages=1315-1321| doi=10.1139/z06-119 }} </ref> [[water bird|aquatic birds]], [[mammal|mammals]] and humans.<ref name="CDC Index" /> A definitive host which is infected with ''Echinostoma'' will shed unembryonated ''Echinostoma'' [[egg|eggs]] in their faeces. When the eggs are in contact with [[fresh water]] they may become embryonated, and will then hatch and release [[trematode lifecycle stages|miracidia]]<ref name="Toledo2012" />. The miracidia stage of ''Echinostoma'' is free-swimming, and actively penetrates the first intermediate snail host, which then becomes infected.<ref name="Toledo2012"> {{Cite journal | author=Toledo R, Esteban JG & Fried B | title= Current status of food-borne trematode infections | journal=[[European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases]] | volume=31 | year=1995 | pages=1705-1718 | doi=10.1007/s10096-011-1515-4 }} </ref> |

|||

[[File:Echinostomiasis Life Cycle no watermark.gif|thumb|right|alt=An illustrated life cycle of the ''Echinostoma'' parasite, beginning with the emergence of unembryonated eggs from an infected person, and ending with mature adults in a host. The life cycle is described in the adjacent text.|Life cycle of ''Echinostoma''.]] |

|||

In the first intermediate host, the miracidium undergoes [[asexual reproduction]]<ref name="Trouve1999"> {{Cite journal | author=Trouvé S, Renaud F, Durand P & Jourdane J | title= Reproductive and mate choice strategies in the hermaphroditic flatworm ''Echinostoma caproni'' | journal=[[Journal of Heredity]] | volume=90| year=1999 | pages=582-585 | doi=10.1093/jhered/90.5.582 }} </ref> for several weeks, which includes [[trematode lifecycle stages|sporocyst]] formation, a few generations of [[trematode lifecycle stages|rediae]] and the production of [[trematode lifecycle stages|cercariae]].<ref name="Toledo2012" /> The cercariae are released from the snail host into water and are also free-swimming. The cercariae penetrate a second intermediate host, or they remain in the first intermediate host, where they form metacercariae.<ref name="CDC Index" /> Definitive hosts become infected by eating secondary hosts which are infected with metacercariae.<ref name="CDC Index" /> Once the metacercariae have been eaten, they excyst in the intestine of the definitive host<ref name="CDC Index" /> where the parasite then develops into an adult. |

|||

''Echinostoma'' are [[hermaphrodite|hermaphrodites]]. A single adult individual has both male and female reproductive organs, and is capable of self-fertilization.<ref name="Trouve1999" /> [[Sexual reproduction]] of adult ''Echinostoma'' in the definitive host leads to the production of unembryonated eggs. <ref name="Toledo2012" /> The life cycle of ''Echinostoma'' is temperature dependent, and occurs quicker at higher temperatures.<ref name="AinP" /> ''Echinostoma'' eggs can survive for about 5 months and still have the ability to hatch and develop into the next life cycle stage.<ref name="Christensen1980">{{Cite journal | author=Christensen NØ, Frandsen F & Roushdy MZ | title= The influence of environmental conditions and parasite-intermediate host-related factors on the transmission of ''Echinostoma liei''| journal=[[Zeitschrift für Parasitenkunde]] | volume=63| year=1980 | pages=47-63 }}</ref> |

|||

==Echinostomiasis== |

|||

[[Infection]] of humans with members of the family Echinostomatidae, including ''Echinostoma'', can lead to a disease called echinostomiasis. ''E. revolutum'', ''E. echinatum'', ''E. malaynum'' and ''E. hortense'' are particularly common causes of ''Echinostoma'' infections in humans.<ref name="AinP" /> Humans can become infected with ''Echinostoma'' by eating infected raw or undercooked [[food]], particularly [[fish]], [[clam|clams]] and snails.<ref name="Toledo2012" /> Infection with these parasites tends to be common in regions where cultural dishes require the use of raw or undercooked food that may be infected with ''Echinostoma''.<ref name="Keiser2005">{{Cite journal | author=Keiser J & Utzinger J | title= Emerging foodborne trematodiasis | journal=[[Emerging Infectious Diseases]] | volume=11 | year=2005 | pages=1507-1514 | doi=10.3201/eid1110.050614 }} </ref> A mild infection may not have any [[symptom|symptoms]].<ref name="Carney1991">{{Cite journal | author=Carney WP | title= Echinostomiasis - a snail-borne intestinal trematode zoonosis| journal=[[Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health]] | volume=22 | year=1991 | pages=Suppl:206-211 }} </ref> If symptoms are present they can include abdominal pain, [[diarrhea|diarrhoea]], tiredness and weight loss.<ref name="Toledo2012" /> |

|||

==Epidemiology of echinostomiasis== |

|||

Echinostomiasis is [[endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]] in South East Asia and the Far East, in countries including [[China]], Korea, [[Taiwan]], Philippines, [[Malaysia]], [[Indonesia]] and [[India]].<ref name="Fried2004"> {{Cite journal | author=Fried B, Graczyk TK & Tamang L | title= Food-borne intestinal trematodiases in humans | journal=[[Parasitology Research]] | volume=93 | year=2004 | pages=159-170 | doi=10.1007/s00436-004-1112-x }} </ref> Echinostomiasis has also been reported in [[Japan]], [[Singapore]], [[Romania]], [[Hungary]] and [[Italy]].<ref name="Fried2004" /> The [[prevalence]] of echinostomiasis varies between countries.<ref name="Fried2004" /> |

|||

==Pathogenesis== |

|||

Clinical features of echinostomiasis are related to the worm burden.<ref name="Carney1991" /> Echinostomatidae cause damage to the intestinal mucosa, which leads to [[ulcer|ulceration]] and [[inflammation]].<ref name="Carney1991" /> |

|||

==Diagnosis== |

|||

[[File:Unstained Echinostoma egg.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Micrograph of an unstained Echinostoma egg |Unstained ''Echinostoma'' egg.]] |

|||

An ''Echinostoma'' infection can be diagnosed by observing the parasite eggs in the [[feces|faeces]] of an infected individual, under a [[microscope]]. Methods such as the Kato-Katz procedure can be used to do this.<ref name="Toledo2012" /> The eggs typically have a yellow-brown appearance, and are ellipsoid in shape.<ref name="Carney1991" /> |

|||

==Treatment and Prevention== |

|||

Echinostomiasis can be treated with the [[anthelmintic]] drug [[praziquantel]], as for other intestinal trematode infections.<ref name="Toledo2012" /> A single dose of praziquantel at 25mg per kg of body weight is recommended to treat an intestinal fluke infection.<ref name="Toledo2012" /> Side effects of anthelmintic drug treatment may include [[nausea]], abdominal pain, [[headache|headaches]] or [[dizziness]].<ref name="Toledo2012" /><ref name="KJUJ2004">{{Cite journal | author=Keiser J & Utzinger J | title= Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review| journal=[[Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy]] | volume=5 | year=2004 | pages=1711-1726| doi=10.1517/14656566.5.8.1711 }} </ref> |

|||

Echinostomiasis can be controlled at the same time as other [[foodborne illness|food-borne]] parasite infections, using existing control programmes.<ref name="Fried2004" /> Interrupting the parasite’s lifecycle by efficient diagnosis and subsequent treatment of infected individuals, and preventing reinfection, may help to control this disease.<ref name="Graczyk1998">{{Cite journal | author=Graczyk TK & Fried B | title= Echinostomiasis: a common but forgotten food-borne disease | journal=[[The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene]] | volume=58 | year=1998 | pages=501-504 }} </ref> As echinostomiasis is acquired through the consumption of raw or undercooked infected food, cooking food thoroughly will prevent infection. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Revision as of 13:57, 27 March 2014

Echinostoma is a genus of trematode parasites, which can infect both humans and animals. These intestinal flukes have a three-host life cycle with snails or aquatic organisms as intermediate hosts, and a variety of animals, including humans, as their definitive hosts.

Echinostoma infect the gastrointestinal tract of humans, and can cause a disease known as echinostomiasis. The parasites are spread when humans or animals eat infected raw or undercooked food, such as bivalve molluscs or fish [1]

| Echinostoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two specimens of Echinostoma revolutum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Echinostoma |

Taxonomy

It has been estimated that there are between 61 and 114 species of Echinostoma.[3] Echinostoma are difficult to classify and are known as a cryptic species (different lineages are considered to be the same species, due to high morphological similarity between them).[4] Many species of Echinostoma have been re-classified several times. For example, the species now known as Echinostoma caproni, was previously known by a variety of names including E. liei, E. parasensei and E. togoensis.[3]

Methods for classifying Echinostoma species, such as the Echinostoma revolutum group, were devised by Kanev.[5] The Echinostoma species in this group are now classified according to their shared morphological and biological characteristics, such as the presence of 37 collar spines.[5]

Molecular methods, such as sequencing mitochondrial DNA and ribosomal DNA, are also used to distinguish between species of Echinostoma as an alternative to morphological classification methods.[6]

Morphology

Echinostoma are internal digenean trematode parasites which infect the intestines and bile duct[3] of their hosts.

The length and width of adult Echinostoma varies between species, but they tend to be approximately 2-10mm x 1-2mm in size.[7]

Adult Echinostoma have two suckers: an anterior oral sucker and a ventral sucker.[3] They also have a characteristic head collar with spines surrounding their oral sucker.[8] The number of collar spines varies between Echinostoma species, but there are usually between 27 and 51.[3] These spines can be arranged in one or two circles around the sucker, and their arrangement may be a characteristic feature of an Echinostoma species.[3]

Echinostoma have a digestive system consisting of a pharynx, oesophagus and an excretory pore.[3]

Echinostoma are hermaphrodites,[8] and have both male and female reproductive organs. The testes are found in the posterior part of the fluke’s body, in the area furthest from the mouth.[3] The ovary is also found in this location, close to the testes.[3]

The eggs (ova) of Echinostoma are operculate [3] and vary in size, but are typically in the range of 80-135μm x 55-80μm.[9]

Geographic Distribution

The genus Echinostoma has a global distribution. These parasites are particularly common in South East Asia, in countries such as South Korea and the Philippines.[10] However, they are also found in some European countries,[5] and species such as Echinostoma trivolvis are found in North America.[11]

Life Cycle

Echinostoma have three hosts in their life cycle: a first intermediate host, a second intermediate host and a definitive host. Snail species such as Lymnaea spp. are common intermediate hosts for Echinostoma,[3] although fish and other bivalve molluscs can be also be intermediate hosts for these parasites. [12]

Echinostoma species have low specificity for their definitive hosts, and can infect a variety of different species of animal, including amphibians,[13] aquatic birds, mammals and humans.[12] A definitive host which is infected with Echinostoma will shed unembryonated Echinostoma eggs in their faeces. When the eggs are in contact with fresh water they may become embryonated, and will then hatch and release miracidia[1]. The miracidia stage of Echinostoma is free-swimming, and actively penetrates the first intermediate snail host, which then becomes infected.[1]

In the first intermediate host, the miracidium undergoes asexual reproduction[14] for several weeks, which includes sporocyst formation, a few generations of rediae and the production of cercariae.[1] The cercariae are released from the snail host into water and are also free-swimming. The cercariae penetrate a second intermediate host, or they remain in the first intermediate host, where they form metacercariae.[12] Definitive hosts become infected by eating secondary hosts which are infected with metacercariae.[12] Once the metacercariae have been eaten, they excyst in the intestine of the definitive host[12] where the parasite then develops into an adult.

Echinostoma are hermaphrodites. A single adult individual has both male and female reproductive organs, and is capable of self-fertilization.[14] Sexual reproduction of adult Echinostoma in the definitive host leads to the production of unembryonated eggs. [1] The life cycle of Echinostoma is temperature dependent, and occurs quicker at higher temperatures.[3] Echinostoma eggs can survive for about 5 months and still have the ability to hatch and develop into the next life cycle stage.[15]

Echinostomiasis

Infection of humans with members of the family Echinostomatidae, including Echinostoma, can lead to a disease called echinostomiasis. E. revolutum, E. echinatum, E. malaynum and E. hortense are particularly common causes of Echinostoma infections in humans.[3] Humans can become infected with Echinostoma by eating infected raw or undercooked food, particularly fish, clams and snails.[1] Infection with these parasites tends to be common in regions where cultural dishes require the use of raw or undercooked food that may be infected with Echinostoma.[16] A mild infection may not have any symptoms.[17] If symptoms are present they can include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, tiredness and weight loss.[1]

Epidemiology of echinostomiasis

Echinostomiasis is endemic in South East Asia and the Far East, in countries including China, Korea, Taiwan, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and India.[18] Echinostomiasis has also been reported in Japan, Singapore, Romania, Hungary and Italy.[18] The prevalence of echinostomiasis varies between countries.[18]

Pathogenesis

Clinical features of echinostomiasis are related to the worm burden.[17] Echinostomatidae cause damage to the intestinal mucosa, which leads to ulceration and inflammation.[17]

Diagnosis

An Echinostoma infection can be diagnosed by observing the parasite eggs in the faeces of an infected individual, under a microscope. Methods such as the Kato-Katz procedure can be used to do this.[1] The eggs typically have a yellow-brown appearance, and are ellipsoid in shape.[17]

Treatment and Prevention

Echinostomiasis can be treated with the anthelmintic drug praziquantel, as for other intestinal trematode infections.[1] A single dose of praziquantel at 25mg per kg of body weight is recommended to treat an intestinal fluke infection.[1] Side effects of anthelmintic drug treatment may include nausea, abdominal pain, headaches or dizziness.[1][19]

Echinostomiasis can be controlled at the same time as other food-borne parasite infections, using existing control programmes.[18] Interrupting the parasite’s lifecycle by efficient diagnosis and subsequent treatment of infected individuals, and preventing reinfection, may help to control this disease.[20] As echinostomiasis is acquired through the consumption of raw or undercooked infected food, cooking food thoroughly will prevent infection.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Toledo R, Esteban JG & Fried B (1995). "Current status of food-borne trematode infections". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 31: 1705–1718. doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1515-4.

- ^ Rudolphi K. (1809). Entoz. Hist. Nat. 2(1): 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Huffman, Jane E; Fried, Bernard (1990). "Echinostoma and Echinostomiasis". In Baker, John R; Muller, Ralph (eds.). Advances in Parasitology. Academic Press Limited. pp. 215–269. ISBN 0-12-031729-X.

- ^ Detwiler JT, Bos DH & Minchella DJ (2010). "Revealing the secret lives of cryptic species: Examining the phylogenetic relationships of echinostome parasites in North America". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 55: 611–620. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.004.

- ^ a b c Kanev I (1994). "Life-cycle, delimitation and redescription of Echinostoma revolutum (Froelich, 1802) (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae)". Systematic Parasitology. 28: 125–144. doi:10.1007/BF00009591. Cite error: The named reference "Kanev1994" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Morgan JAT & Blair D (1998). "Relative merits of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacers and mitochondrial CO1 and ND1 genes for distinguishing among Echinostoma species (Trematoda)". Parasitology. 116: 289–297.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Echinostomiasis". Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b

Gonçalves JP, Oliveira-Menezes A, Maldonado Junior A; et al. (2013). "Evaluation of Praziquantel effects on

Echinostoma paraensei ultrastructure". Veterinary Parasitology. 194: 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.042.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); line feed character in|title=at position 38 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (29 November 2013). "Echinostomiasis". Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ^ Fürst T, Keiser J & Utzinger A (2012). "Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12: 210–221. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70294-8.

- ^ Kanev I, Fried B, Dimitrov V & Radev V (1995). "Redescription of Echinostoma trivolvis (Cort, 1914) (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) with a discussion on its identity". Systematic Parasitology. 32: 61–70. doi:10.1007/BF00009468.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (29 November 2013). "Echinostomiasis". Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ^ Belden LK (2006). "Impact of eutrophication on wood frog, Rana sylvatica, tadpoles infected with Echinostoma trivolvis cercariae". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 84: 1315–1321. doi:10.1139/z06-119.

- ^ a b Trouvé S, Renaud F, Durand P & Jourdane J (1999). "Reproductive and mate choice strategies in the hermaphroditic flatworm Echinostoma caproni". Journal of Heredity. 90: 582–585. doi:10.1093/jhered/90.5.582.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Christensen NØ, Frandsen F & Roushdy MZ (1980). "The influence of environmental conditions and parasite-intermediate host-related factors on the transmission of Echinostoma liei". Zeitschrift für Parasitenkunde. 63: 47–63.

- ^ Keiser J & Utzinger J (2005). "Emerging foodborne trematodiasis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11: 1507–1514. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050614.

- ^ a b c d Carney WP (1991). "Echinostomiasis - a snail-borne intestinal trematode zoonosis". Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 22: Suppl:206-211.

- ^ a b c d Fried B, Graczyk TK & Tamang L (2004). "Food-borne intestinal trematodiases in humans". Parasitology Research. 93: 159–170. doi:10.1007/s00436-004-1112-x.

- ^ Keiser J & Utzinger J (2004). "Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 5: 1711–1726. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.8.1711.

- ^ Graczyk TK & Fried B (1998). "Echinostomiasis: a common but forgotten food-borne disease". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 58: 501–504.