Argument map: Difference between revisions

m →References: added Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments |

revised article slightly |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

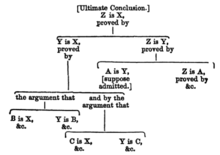

A number of different kinds of argument map have been proposed but the most common, which Chris Reed and Glenn Rowe called the ''standard diagram'',<ref name="ReedRowe64">{{harvnb|Reed|Rowe|2007|p=64}}</ref> consists of a [[tree structure]] with each of the reasons leading to the conclusion. There is no consensus as to whether the conclusion should be at the top of the tree with the reasons leading up to it or whether it should be at the bottom with the reasons leading down to it.<ref name="ReedRowe64"/> Another variation diagrams an argument from left to right.<ref>For example: {{harvnb|Walton|2013|pp=18–20}}</ref> |

A number of different kinds of argument map have been proposed but the most common, which Chris Reed and Glenn Rowe called the ''standard diagram'',<ref name="ReedRowe64">{{harvnb|Reed|Rowe|2007|p=64}}</ref> consists of a [[tree structure]] with each of the reasons leading to the conclusion. There is no consensus as to whether the conclusion should be at the top of the tree with the reasons leading up to it or whether it should be at the bottom with the reasons leading down to it.<ref name="ReedRowe64"/> Another variation diagrams an argument from left to right.<ref>For example: {{harvnb|Walton|2013|pp=18–20}}</ref> |

||

According to [[Doug Walton]] and colleagues, an argument map has two basic components: "One component is a set of circled numbers arrayed as points. Each number represents a proposition (premise or conclusion) in the argument being diagrammed. The other component is a set of lines or arrows joining the points. Each line (arrow) represents an inference. The whole network of points and lines represents a kind of overview of the reasoning in the given argument..."<ref>{{harvnb|Reed |

According to [[Doug Walton]] and colleagues, an argument map has two basic components: "One component is a set of circled numbers arrayed as points. Each number represents a proposition (premise or conclusion) in the argument being diagrammed. The other component is a set of lines or arrows joining the points. Each line (arrow) represents an inference. The whole network of points and lines represents a kind of overview of the reasoning in the given argument..."<ref>{{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007|p=2}}</ref> With the introduction of software for producing argument maps, it has become common for argument maps to consist of boxes containing the actual propositions rather than numbers referencing those propositions. |

||

There is disagreement on the terminology to be used when describing argument maps,<ref>{{harvnb|Freeman|1991|pp=49–90}}; {{harvnb|Reed|Rowe|2007}}</ref> but the ''standard diagram'' contains the following structures: |

There is disagreement on the terminology to be used when describing argument maps,<ref>{{harvnb|Freeman|1991|pp=49–90}}; {{harvnb|Reed|Rowe|2007}}</ref> but the ''standard diagram'' contains the following structures: |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

[[File:Independent premises.jpg|thumb|centre|150px|Statements 2, 3, 4 are independent premises]] |

[[File:Independent premises.jpg|thumb|centre|150px|Statements 2, 3, 4 are independent premises]] |

||

'''Intermediate conclusions''' or '''sub-conclusions''', where a claim is supported by another claim that is used in turn to support some further claim, i.e. the final conclusion or another intermediate conclusion: In the following diagram, statement '''4''' is an intermediate conclusion in that it is a conclusion in relation to statement '''5''' but is a premise in relation to the final conclusion, i.e. statement '''1'''. An argument with this structure is sometimes called a ''complex'' argument. If there is a single chain of claims containing at least one intermediate conclusion, the argument is sometimes described as a ''serial'' argument or a ''chain'' argument.<ref>{{harvnb|Beardsley|1950|pp=18–19}}; {{harvnb|Reed |

'''Intermediate conclusions''' or '''sub-conclusions''', where a claim is supported by another claim that is used in turn to support some further claim, i.e. the final conclusion or another intermediate conclusion: In the following diagram, statement '''4''' is an intermediate conclusion in that it is a conclusion in relation to statement '''5''' but is a premise in relation to the final conclusion, i.e. statement '''1'''. An argument with this structure is sometimes called a ''complex'' argument. If there is a single chain of claims containing at least one intermediate conclusion, the argument is sometimes described as a ''serial'' argument or a ''chain'' argument.<ref>{{harvnb|Beardsley|1950|pp=18–19}}; {{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007|pp=3–8}}; {{harvnb|Harrell|2010|pp=19–21}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Intermediate conclusion.jpg|thumb|centre|150px|Statement 4 is an intermediate conclusion or sub-conclusion]] |

[[File:Intermediate conclusion.jpg|thumb|centre|150px|Statement 4 is an intermediate conclusion or sub-conclusion]] |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Representing an argument as an argument map== |

==Representing an argument as an argument map== |

||

A written |

A written text can be transformed into an argument map by following a sequence of steps. [[Monroe Beardsley]]'s 1950 book ''Practical Logic'' recommended the following procedure:<ref name="Beardsley">{{harvnb|Beardsley|1950}}</ref> |

||

#Separate statements by brackets and number them. |

#Separate statements by brackets and number them. |

||

#Put circles around the logical indicators. |

#Put circles around the logical indicators. |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

[[File:Diagram using Beardsley's procedure.jpg|thumb|right|100px|A diagram of the example from Beardsley's ''Practical Logic'']] |

[[File:Diagram using Beardsley's procedure.jpg|thumb|right|100px|A diagram of the example from Beardsley's ''Practical Logic'']] |

||

Beardsley |

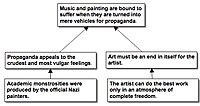

Beardsley gave the first example of a text being analysed in this way: |

||

:Though <span style='color: red;'>① [</span>people who talk about the "social significance" of the arts don’t like to admit it<span style='color: red;'>]</span>, <span style='color: red;'>② [</span>music and painting are bound to suffer when they are turned into mere vehicles for propaganda<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. <span style='width: 100%; border: solid 2px blue;padding-left:5px;padding-right:5px;border-radius: 25px;'>For</span> <span style='color: red;'>③ [</span>propaganda appeals to the crudest and most vulgar feelings<span style='color: red;'>]</span>: <span style='color: red;'>(for)</span> <span style='color: red;'>④ [</span>look at the academic monstrosities produced by the official Nazi painters<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. What is more important, <span style='color: red;'>⑤ [</span>art must be an end in itself for the artist<span style='color: red;'>]</span>, <span style='width: 100%; border: solid 2px blue;padding-left:5px;padding-right:5px;border-radius: 25px;'>because</span> <span style='color: red;'>⑥ [</span>the artist can do the best work only in an atmosphere of complete freedom<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. |

:Though <span style='color: red;'>① [</span>people who talk about the "social significance" of the arts don’t like to admit it<span style='color: red;'>]</span>, <span style='color: red;'>② [</span>music and painting are bound to suffer when they are turned into mere vehicles for propaganda<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. <span style='width: 100%; border: solid 2px blue;padding-left:5px;padding-right:5px;border-radius: 25px;'>For</span> <span style='color: red;'>③ [</span>propaganda appeals to the crudest and most vulgar feelings<span style='color: red;'>]</span>: <span style='color: red;'>(for)</span> <span style='color: red;'>④ [</span>look at the academic monstrosities produced by the official Nazi painters<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. What is more important, <span style='color: red;'>⑤ [</span>art must be an end in itself for the artist<span style='color: red;'>]</span>, <span style='width: 100%; border: solid 2px blue;padding-left:5px;padding-right:5px;border-radius: 25px;'>because</span> <span style='color: red;'>⑥ [</span>the artist can do the best work only in an atmosphere of complete freedom<span style='color: red;'>]</span>. |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

Dealing with the failure of [[Formal system|formal]] reduction of informal argumentation, English speaking [[argumentation theory]] developed diagrammatic approaches to informal reasoning over a period of fifty years. |

Dealing with the failure of [[Formal system|formal]] reduction of informal argumentation, English speaking [[argumentation theory]] developed diagrammatic approaches to informal reasoning over a period of fifty years. |

||

[[Monroe Beardsley]] proposed a form of argument diagram in 1950.<ref name="Beardsley"/> His method of marking up an argument and representing its components with linked numbers became a standard and is still widely used. He also introduced terminology that is still current describing 'convergent', 'divergent' and 'serial' arguments. |

[[Monroe Beardsley]] proposed a form of argument diagram in 1950.<ref name="Beardsley"/> His method of marking up an argument and representing its components with linked numbers became a standard and is still widely used. He also introduced terminology that is still current describing ''convergent'', ''divergent'' and ''serial'' arguments. |

||

Beardsley's approach was refined by Stephen N. Thomas |

Beardsley's approach was refined by Stephen N. Thomas, whose book ''Practical Reasoning In Natural Language''<ref>{{harvnb|Thomas|1997}} (first published 1973)</ref> introduced the term ''linked'' to describe arguments where the premises necessarily worked together to support the conclusion.<ref name="SnoeckHenkemans">{{harvnb|Snoeck Henkemans|2000|p=453}}</ref> However, the actual distinction between dependent and independent premises had been made prior to this.<ref name="SnoeckHenkemans"/> The introduction of the linked structure made it possible for argument maps to represent missing or "hidden" premises. In addition, Thomas suggested suggested showing reasons both ''for'' and ''against'' a conclusion with the reasons ''against'' being represented by dotted arrows. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Stephen Toulmin]], in his groundbreaking and influential 1958 book ''The Uses of Argument |

||

[[File:Toulmindiag.png|thumb|A Toulmin argument diagram, redrawn from his 1959 ''Uses of Argument'']] |

[[File:Toulmindiag.png|thumb|A Toulmin argument diagram, redrawn from his 1959 ''Uses of Argument'']] |

||

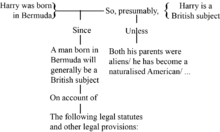

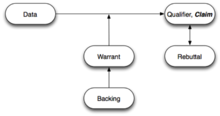

| ⚫ | [[Stephen Toulmin]], in his groundbreaking and influential 1958 book ''The Uses of Argument'',<ref>{{harvnb|Toulmin|2003}} (first published 1958)</ref> identified several elements to an argument which have been generalized. The Toulmin diagram is widely used in educational critical teaching.<ref name="Simon06">{{harvnb|Simon|Erduran|Osborne|2006}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Böttcher|Meisert|2011}}; {{harvnb|Macagno|Konstantinidou|2013}}</ref> Toulmin introduced something that was missing from Beardsley's approach. In Beardsley, "arrows link reasons and conclusions (but) no support is given to the implication itself between them. There is no theory, in other words, of inference distinguished from logical deduction, the passage is always deemed not controversial an not subject to support and evaluation".<ref>{{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007|p=8}}</ref> Toulmin introduced the concept of ''warrant'' which "can be considered as representing the reasons behind the inference, the backing that authorizes the link".<ref>{{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007|p=9}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Toulmingeneral.png|thumb|A generalised Toulmin diagram]] |

[[File:Toulmingeneral.png|thumb|A generalised Toulmin diagram]] |

||

[[Michael Scriven]] developed an argument diagram in 1976.<ref>{{harvnb|Scriven|1976}}</ref> |

[[Michael Scriven]] developed an argument diagram in 1976.<ref>{{harvnb|Scriven|1976}}</ref> Scriven introduced counterarguments in his diagrams, which Toulmin had defined as rebuttal. Scriven also indicated missing premises with an alphabetical letter instead of a number.<ref>{{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007|p=10–11}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Scrivendiag.png|thumb|Scriven's argument diagram. The major premise 1 is conjoined with additional minor premises a and b to imply 2.]] |

[[File:Scrivendiag.png|thumb|Scriven's argument diagram. The major premise 1 is conjoined with additional minor premises a and b to imply 2.]] |

||

In 1988, [[David Kelley]] proposed a structured diagram technique with numbered premises, and arrows indicating inferential relations, very similar to Beardsley's earlier approach.<ref>{{harvnb|Kelley|1988}}</ref> The premises were to be listed at the side of the diagram for reference. The three forms here of an argument are 'serial', 'additive' (or joint), and 'non-additive' (or convergent), respectively. |

In 1988, [[David Kelley]] proposed a structured diagram technique with numbered premises, and arrows indicating inferential relations, very similar to Beardsley's earlier approach.<ref>{{harvnb|Kelley|1988}}</ref> The premises were to be listed at the side of the diagram for reference. The three forms here of an argument are ''serial'', ''additive'' (or joint), and ''non-additive'' (or convergent), respectively. |

||

[[File:Kelleydiag.png|thumb|A Kelley argument diagram. The left argument is a "serial" argument, the middle is an "additive" argument, where multiple premises must be employed, and the right is a "non-additive" argument where several premises independently support a conclusion.]] |

[[File:Kelleydiag.png|thumb|A Kelley argument diagram. The left argument is a "serial" argument, the middle is an "additive" argument, where multiple premises must be employed, and the right is a "non-additive" argument where several premises independently support a conclusion.]] |

||

In the 1990s, [[Tim van Gelder]] and colleagues developed a series of computer software applications that permitted the premises to be fully stated and edited in the diagram, rather than in a legend.<ref>{{harvnb|van Gelder|2007}}</ref> |

In the 1990s, [[Tim van Gelder]] and colleagues developed a series of computer software applications that permitted the premises to be fully stated and edited in the diagram, rather than in a legend.<ref>{{harvnb|van Gelder|2007}}</ref> Van Gelder's first program, Reason!Able, was superseded by two subsequent programs, bCisive and Rationale.<ref>{{harvnb|Berg|van Gelder|Patterson|Teppema|2009}}</ref> |

||

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, many other software applications were developed for argument visualization. By 2013, more than 60 such software systems existed.<ref>{{harvnb|Walton|2013|p=11}}</ref> One of the differences between these software systems is whether collaboration is supported.<ref name="Scheuer10">{{harvnb|Scheuer|Loll|Pinkwart|McLaren|2010}}</ref> Single-user argumentation systems include Convince Me, iLogos, LARGO, Athena, [[Araucaria (software)|Araucaria]], and Carneades; small group argumentation systems include Digalo, QuestMap, [[Compendium (software)|Compendium]], Belvedere, and AcademicTalk; community argumentation systems include [[Debategraph]] and [[Collaboratorium]].<ref name="Scheuer10"/> For more software examples, see: {{section link||External links}}. |

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, many other software applications were developed for argument visualization. By 2013, more than 60 such software systems existed.<ref>{{harvnb|Walton|2013|p=11}}</ref> One of the differences between these software systems is whether collaboration is supported.<ref name="Scheuer10">{{harvnb|Scheuer|Loll|Pinkwart|McLaren|2010}}</ref> Single-user argumentation systems include Convince Me, iLogos, LARGO, Athena, [[Araucaria (software)|Araucaria]], and Carneades; small group argumentation systems include Digalo, QuestMap, [[Compendium (software)|Compendium]], Belvedere, and AcademicTalk; community argumentation systems include [[Debategraph]] and [[Collaboratorium]].<ref name="Scheuer10"/> For more software examples, see: {{section link||External links}}. |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

==Applications== |

==Applications== |

||

Argument maps have been applied in many areas, but foremost in educational, academic and business settings.<ref name="Applications">{{harvnb|Kirschner|Buckingham Shum|Carr|2003}}; {{harvnb|Okada|Buckingham Shum|Sherborne|2008}}</ref> It has also been proposed that argument mapping has a great potential to improve how we understand and execute democracy, in reference to the ongoing evolution of [[e-democracy]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hilbert|2009}}</ref> |

Argument maps have been applied in many areas, but foremost in educational, academic and business settings, including [[design rationale]].<ref name="Applications">{{harvnb|Kirschner|Buckingham Shum|Carr|2003}}; {{harvnb|Okada|Buckingham Shum|Sherborne|2008}}</ref> Argument maps are also used in [[forensic science]],<ref>For example: {{harvnb|Bex|2011}}</ref> [[law]], and [[artificial intelligence]].<ref>For example: {{harvnb|Verheij|2005}}; {{harvnb|Reed|Walton|Macagno|2007}}; {{harvnb|Walton|2013}}</ref> It has also been proposed that argument mapping has a great potential to improve how we understand and execute democracy, in reference to the ongoing evolution of [[e-democracy]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hilbert|2009}}</ref> |

||

===Difficulties with the philosophical tradition=== |

===Difficulties with the philosophical tradition=== |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Beardsley |first=Monroe C. |authorlink=Monroe Beardsley |date=1950 |title=Practical logic |location=New York |publisher=Prentice-Hall |oclc=4318971 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Beardsley |first=Monroe C. |authorlink=Monroe Beardsley |date=1950 |title=Practical logic |location=New York |publisher=Prentice-Hall |oclc=4318971 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Berg |first1=Timo ter |last2=van Gelder |first2=Tim |authorlink2=Tim van Gelder |last3=Patterson |first3=Fiona |last4=Teppema |first4=Sytske |year=2009 |title=Critical thinking: reasoning and communicating with Rationale |location=Amsterdam |publisher=Pearson Education Benelux |isbn=9043018015 |oclc=301884530 |url=http://www.rationaleonline.com/ebook/e-book/Critical%20Thinking,%20Reasoning%20and%20Communicating%20with%20Rationale.html |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Berg |first1=Timo ter |last2=van Gelder |first2=Tim |authorlink2=Tim van Gelder |last3=Patterson |first3=Fiona |last4=Teppema |first4=Sytske |year=2009 |title=Critical thinking: reasoning and communicating with Rationale |location=Amsterdam |publisher=Pearson Education Benelux |isbn=9043018015 |oclc=301884530 |url=http://www.rationaleonline.com/ebook/e-book/Critical%20Thinking,%20Reasoning%20and%20Communicating%20with%20Rationale.html |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Bex |first=Floris J. |date=2011 |title=Arguments, stories and criminal evidence: a formal hybrid theory |series=Law and philosophy library |volume=92 |location=Dordrecht; New York |publisher=Springer |isbn=9789400701397 |oclc=663950184 |doi=10.1007/978-94-007-0140-3 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Bex |first1=Floris |last2=Modgil |first2=Sanjay |last3=Prakken |first3=Henry |last4=Reed |first4=Chris |title=On logical specifications of the Argument Interchange Format |journal=[[Journal of Logic and Computation]] |volume=23 |issue=5 |pages=951–989 |year=2013 |doi=10.1093/logcom/exs033 |url=http://www.arg.dundee.ac.uk/people/chris/publications/2013/AIF-ASPIC-JLC-Final.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Bex |first1=Floris J. |last2=Modgil |first2=Sanjay |last3=Prakken |first3=Henry |last4=Reed |first4=Chris |title=On logical specifications of the Argument Interchange Format |journal=[[Journal of Logic and Computation]] |volume=23 |issue=5 |pages=951–989 |year=2013 |doi=10.1093/logcom/exs033 |url=http://www.arg.dundee.ac.uk/people/chris/publications/2013/AIF-ASPIC-JLC-Final.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Böttcher |first1=Florian |last2=Meisert |first2=Anke |title=Argumentation in science education: a model-based framework |journal=Science & Education |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=103–140 |date=February 2011 |doi=10.1007/s11191-010-9304-5 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Böttcher |first1=Florian |last2=Meisert |first2=Anke |title=Argumentation in science education: a model-based framework |journal=Science & Education |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=103–140 |date=February 2011 |doi=10.1007/s11191-010-9304-5 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Carrington |first1=Michal |last2=Chen |first2=Richard |last3=Davies |first3=Martin |last4=Kaur |first4=Jagjit |last5=Neville |first5=Benjamin |title=The effectiveness of a single intervention of computer‐aided argument mapping in a marketing and a financial accounting subject |journal=Higher Education Research & Development |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=387–403 |date=June 2011 |doi=10.1080/07294360.2011.559197 |url=http://www.researchgate.net/publication/232947753_The_effectiveness_of_a_single_intervention_of_computeraided_argument_mapping_in_a_marketing_and_a_financial_accounting_subject/file/3deec51d94fec63bdc.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Carrington |first1=Michal |last2=Chen |first2=Richard |last3=Davies |first3=Martin |last4=Kaur |first4=Jagjit |last5=Neville |first5=Benjamin |title=The effectiveness of a single intervention of computer‐aided argument mapping in a marketing and a financial accounting subject |journal=Higher Education Research & Development |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=387–403 |date=June 2011 |doi=10.1080/07294360.2011.559197 |url=http://www.researchgate.net/publication/232947753_The_effectiveness_of_a_single_intervention_of_computeraided_argument_mapping_in_a_marketing_and_a_financial_accounting_subject/file/3deec51d94fec63bdc.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Davies |first=Martin |title=Computer-aided argument mapping as a tool for teaching critical thinking |journal=[[International Journal of Learning and Media]] |volume=4 |issue=3-4 |pages=79–84 |date=Summer 2012 |doi=10.1162/IJLM_a_00106 |url=http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/IJLM_a_00106 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last=Davies |first=Martin |title=Computer-aided argument mapping as a tool for teaching critical thinking |journal=[[International Journal of Learning and Media]] |volume=4 |issue=3-4 |pages=79–84 |date=Summer 2012 |doi=10.1162/IJLM_a_00106 |url=http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/IJLM_a_00106 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite thesis |type=Ph.D. |last=Dwyer |first=Christopher Peter |title=The evaluation of argument mapping as a learning tool |url=http://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10379/2617/C.Dwyer-PhD%20Thesis%20Psychology.pdf |year=2011 |publisher=School of Psychology, National University of Ireland, Galway |oclc=812818648 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite thesis |type=Ph.D. |last=Dwyer |first=Christopher Peter |title=The evaluation of argument mapping as a learning tool |url=http://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10379/2617/C.Dwyer-PhD%20Thesis%20Psychology.pdf |year=2011 |publisher=School of Psychology, National University of Ireland, Galway |oclc=812818648 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=van Eemeren |first1=Frans |last2=Grootendorst |first2=Rob |last3=Johnson |first3=Ralph |last4=Plantin |first4=Christian |last4=Willard |first4=Charles |date=1996 |title=Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0805818628 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Facione |first=Peter A. |title=THINK critically |year=2013 |origyear=2011 |edition=2nd |location=Boston |publisher=Pearson |isbn=0205490980 |oclc=770694200 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Facione |first=Peter A. |title=THINK critically |year=2013 |origyear=2011 |edition=2nd |location=Boston |publisher=Pearson |isbn=0205490980 |oclc=770694200 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Fisher |first=Alec |title=The logic of real arguments |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Q2a_RtDZUGgC |year=2004 |origyear=1988 |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0521654815 |oclc=54400059 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511818455 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Fisher |first=Alec |title=The logic of real arguments |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Q2a_RtDZUGgC |year=2004 |origyear=1988 |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0521654815 |oclc=54400059 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511818455 |ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

* {{cite book |editor1-last=Okada |editor1-first=Alexandra |editor2-last=Buckingham Shum |editor2-first=Simon J |editor3-last=Sherborne |editor3-first=Tony |year=2008 |title=Knowledge cartography: software tools and mapping techniques |location=New York |publisher=Springer |isbn=9781848001480 |oclc=195735592 |doi=10.1007/978-1-84800-149-7 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=vxe2N0YZB84C |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |editor1-last=Okada |editor1-first=Alexandra |editor2-last=Buckingham Shum |editor2-first=Simon J |editor3-last=Sherborne |editor3-first=Tony |year=2008 |title=Knowledge cartography: software tools and mapping techniques |location=New York |publisher=Springer |isbn=9781848001480 |oclc=195735592 |doi=10.1007/978-1-84800-149-7 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=vxe2N0YZB84C |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Reed |first1=Chris |last2=Rowe |first2=Glenn |title=A pluralist approach to argument diagramming |journal=Law, Probability and Risk |volume=6 |issue=1-4 |pages=59–85 |year=2007 |doi=10.1093/lpr/mgm030 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Reed |first1=Chris |last2=Rowe |first2=Glenn |title=A pluralist approach to argument diagramming |journal=Law, Probability and Risk |volume=6 |issue=1-4 |pages=59–85 |year=2007 |doi=10.1093/lpr/mgm030 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Reed |first1=Chris |last2= |

* {{cite journal |last1=Reed |first1=Chris |last2=Walton |first2=Douglas |authorlink2=Doug Walton |last3=Macagno |first3=Fabrizio |title=Argument diagramming in logic, law and artificial intelligence |journal=The Knowledge Engineering Review |volume=22 |issue=1 |pages=1–22 |date=March 2007 |doi=10.1017/S0269888907001051 |url=https://www.academia.edu/2992281/Argument_Diagramming_in_Logic_Artificial_Intelligence_and_Law |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Scheuer |first1=Oliver |last2=Loll |first2=Frank |last3=Pinkwart |first3=Niels |last4=McLaren |first4=Bruce M. |title=Computer-supported argumentation: a review of the state of the art |journal=International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=43–102 |year=2010 |doi=10.1007/s11412-009-9080-x |url=http://www.oliver-scheuer.info/publications/ScheuerEtAl-EdArgSystemsReview-IJCSCL-2010.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Scheuer |first1=Oliver |last2=Loll |first2=Frank |last3=Pinkwart |first3=Niels |last4=McLaren |first4=Bruce M. |title=Computer-supported argumentation: a review of the state of the art |journal=International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=43–102 |year=2010 |doi=10.1007/s11412-009-9080-x |url=http://www.oliver-scheuer.info/publications/ScheuerEtAl-EdArgSystemsReview-IJCSCL-2010.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Scriven |first=Michael |authorlink=Michael Scriven |title=Reasoning |year=1976 |location=New York |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=0070558825 |oclc=2800373 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Scriven |first=Michael |authorlink=Michael Scriven |title=Reasoning |year=1976 |location=New York |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=0070558825 |oclc=2800373 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Simon |first1=Shirley |last2=Erduran |first2=Sibel |last3=Osborne |first3=Jonathan |title=Learning to teach argumentation: research and development in the science classroom |journal=International Journal of Science Education |volume=28 |issue=2-3 |pages=235–260 |year=2006 |doi=10.1080/09500690500336957 |url=http://cset.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/files/documents/publications/Simon-Learning%20to%20Teach%20Argumentation.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Simon |first1=Shirley |last2=Erduran |first2=Sibel |last3=Osborne |first3=Jonathan |title=Learning to teach argumentation: research and development in the science classroom |journal=International Journal of Science Education |volume=28 |issue=2-3 |pages=235–260 |year=2006 |doi=10.1080/09500690500336957 |url=http://cset.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/files/documents/publications/Simon-Learning%20to%20Teach%20Argumentation.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Snoeck Henkemans |first=A. Francisca |date=November 2000 |title=State-of-the-art: the structure of argumentation |journal=Argumentation |volume=14 |issue=4 |pages=447–473 |doi=10.1023/A:1007800305762 |url=http://logic.sysu.edu.cn/Soft/UploadSoft/200712/20071223160059249.pdf |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Thomas |first=Stephen N. |date=1997 |origyear=1973 |title=Practical reasoning in natural language |edition=4th |location=Upper Saddle River, NJ |publisher=[[Prentice-Hall]] |isbn=0136782698 |oclc=34745923 |ref=harv}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Toulmin |first=Stephen E. |authorlink=Stephen Toulmin |title=The uses of argument |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=8UYgegaB1S0C |year=2003 |origyear=1958 |edition=Updated |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0521534836 |oclc=57253830 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511840005 }} |

* {{cite book |last=Toulmin |first=Stephen E. |authorlink=Stephen Toulmin |title=The uses of argument |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=8UYgegaB1S0C |year=2003 |origyear=1958 |edition=Updated |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0521534836 |oclc=57253830 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511840005 }} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Twardy |first=Charles R. |title=Argument maps improve critical thinking |journal=[[Teaching Philosophy]] |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=95–116 |date=June 2004 |doi=10.5840/teachphil200427213 |url=http://cogprints.org/3008/1/reasonpaper.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last=Twardy |first=Charles R. |title=Argument maps improve critical thinking |journal=[[Teaching Philosophy]] |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=95–116 |date=June 2004 |doi=10.5840/teachphil200427213 |url=http://cogprints.org/3008/1/reasonpaper.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |authorlink=Doug Walton |title=Methods of argumentation |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=vaU0AAAAQBAJ |year=2013 |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=1107677335 |oclc=830523850 |doi=10.1017/CBO9781139600187 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |authorlink=Doug Walton |title=Methods of argumentation |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=vaU0AAAAQBAJ |year=2013 |location=Cambridge; New York |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=1107677335 |oclc=830523850 |doi=10.1017/CBO9781139600187 |ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Whately |first=Richard |authorlink=Richard Whately |title=Elements of logic: comprising the substance of the article in the Encyclopædia metropolitana: with additions, &c. |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5mgAAAAAMAAJ |year=1834 |origyear=1826 |edition=5th |location=London |publisher=B. Fellowes |oclc=1739330 |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite book |last=Whately |first=Richard |authorlink=Richard Whately |title=Elements of logic: comprising the substance of the article in the Encyclopædia metropolitana: with additions, &c. |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5mgAAAAAMAAJ |year=1834 |origyear=1826 |edition=5th |location=London |publisher=B. Fellowes |oclc=1739330 |ref=harv}} |

||

| Line 193: | Line 196: | ||

* {{cite web |last=van Gelder |first=Tim |authorlink=Tim van Gelder |url=http://timvangelder.com/2009/02/17/what-is-argument-mapping/ |title=What is argument mapping? |publisher=timvangelder.com |date=17 February 2009 |accessdate=12 January 2015}} |

* {{cite web |last=van Gelder |first=Tim |authorlink=Tim van Gelder |url=http://timvangelder.com/2009/02/17/what-is-argument-mapping/ |title=What is argument mapping? |publisher=timvangelder.com |date=17 February 2009 |accessdate=12 January 2015}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Harrell |first=Maralee |title=Using argument diagramming software in the classroom |journal=[[Teaching Philosophy]] |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=163–177 |date=June 2005 |doi=10.5840/teachphil200528222 |url=http://www.hss.cmu.edu/philosophy/harrell/ArgumentDiagramsInClassroom.pdf |ref=harv}} |

* {{cite journal |last=Harrell |first=Maralee |title=Using argument diagramming software in the classroom |journal=[[Teaching Philosophy]] |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=163–177 |date=June 2005 |doi=10.5840/teachphil200528222 |url=http://www.hss.cmu.edu/philosophy/harrell/ArgumentDiagramsInClassroom.pdf |ref=harv}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

Revision as of 02:44, 3 January 2016

In informal logic and philosophy, an argument map or argument diagram is a visual representation of the structure of an argument. An argument map typically includes the key components of the argument, traditionally called the conclusion and the premises, also called contention and reasons.[1] Argument maps can also show co-premises, objections, counterarguments, rebuttals, and lemmas. There are different styles of argument map but they are often functionally equivalent and represent an argument's individual claims and the relationships between them.

Argument maps are commonly used in the context of teaching and applying critical thinking.[2] The purpose of mapping is to uncover the logical structure of arguments, identify unstated assumptions, evaluate the support an argument offers for a conclusion, and aid understanding of debates. Argument maps are often designed to support deliberation of issues, ideas and arguments in wicked problems.[3]

An argument map is not to be confused with a concept map or a mind map, which are less strict in relating claims.

Key features of an argument map

A number of different kinds of argument map have been proposed but the most common, which Chris Reed and Glenn Rowe called the standard diagram,[4] consists of a tree structure with each of the reasons leading to the conclusion. There is no consensus as to whether the conclusion should be at the top of the tree with the reasons leading up to it or whether it should be at the bottom with the reasons leading down to it.[4] Another variation diagrams an argument from left to right.[5]

According to Doug Walton and colleagues, an argument map has two basic components: "One component is a set of circled numbers arrayed as points. Each number represents a proposition (premise or conclusion) in the argument being diagrammed. The other component is a set of lines or arrows joining the points. Each line (arrow) represents an inference. The whole network of points and lines represents a kind of overview of the reasoning in the given argument..."[6] With the introduction of software for producing argument maps, it has become common for argument maps to consist of boxes containing the actual propositions rather than numbers referencing those propositions.

There is disagreement on the terminology to be used when describing argument maps,[7] but the standard diagram contains the following structures:

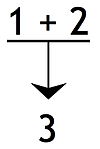

Dependent premises or co-premises, where at least one of the joined premises requires another premise before it can give support to the conclusion: An argument with this structure has been called a linked argument.[8]

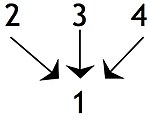

Independent premises, where the premise can support the conclusion on its own: Although independent premises may jointly make the conclusion more convincing, this is to be distinguished from situations where a premise gives no support unless it is joined to another premise. Where several premises or groups of premises lead to a final conclusion the argument might be described as convergent. This is distinguished from a divergent argument where a single premise might be used to support two separate conclusions.[9]

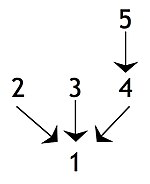

Intermediate conclusions or sub-conclusions, where a claim is supported by another claim that is used in turn to support some further claim, i.e. the final conclusion or another intermediate conclusion: In the following diagram, statement 4 is an intermediate conclusion in that it is a conclusion in relation to statement 5 but is a premise in relation to the final conclusion, i.e. statement 1. An argument with this structure is sometimes called a complex argument. If there is a single chain of claims containing at least one intermediate conclusion, the argument is sometimes described as a serial argument or a chain argument.[10]

Each of these structures can be represented by the equivalent "box and line" approach to argument maps. In the following diagram, the conclusion is shown at the top, and the boxes linked to it represent supporting reasons, which comprise one or more premises. The reason, 1A, comprising two premises 1A-a and 1A-b, support the conclusion:

Argument maps can also represent counterarguments. In the following diagram, the objection 1A weakens the conclusion, while the reason 2A supports premise 1A-b of the objection:

Representing an argument as an argument map

A written text can be transformed into an argument map by following a sequence of steps. Monroe Beardsley's 1950 book Practical Logic recommended the following procedure:[11]

- Separate statements by brackets and number them.

- Put circles around the logical indicators.

- Supply, in parenthesis, any logical indicators that are left out.

- Set out the statements in a diagram in which arrows show the relationships between statements.

Beardsley gave the first example of a text being analysed in this way:

- Though ① [people who talk about the "social significance" of the arts don’t like to admit it], ② [music and painting are bound to suffer when they are turned into mere vehicles for propaganda]. For ③ [propaganda appeals to the crudest and most vulgar feelings]: (for) ④ [look at the academic monstrosities produced by the official Nazi painters]. What is more important, ⑤ [art must be an end in itself for the artist], because ⑥ [the artist can do the best work only in an atmosphere of complete freedom].

Beardsley said that the conclusion in this example is statement ②. Statement ④ needs to be rewritten as a declarative sentence, e.g. "Academic monstrosities [were] produced by the official Nazi painters." Statement ① points out that the conclusion isn't accepted by everyone, but statement ① is omitted from the diagram because it doesn't support the conclusion. Beardsley said that the logical relation between statement ③ and statement ④ is unclear, but he proposed to diagram statement ④ as supporting statement ③.

More recently, philosophy professor Maralee Harrell recommended the following procedure:[12]

- Identify all the claims being made by the author.

- Rewrite them as independent statements, eliminating non-essential words.

- Identify which statements are premises, sub-conclusions, and the main conclusion.

- Providing missing, implied conclusions and implied premises. (This is optional depending on the purpose of the argument map.)

- Put the statements into boxes and draw a line between any boxes that are linked.

- Indicate support from premise(s) to (sub)conclusion with arrows.

Argument maps are useful not only for representing and analyzing existing writings, but also for thinking through issues as part of a problem-structuring process or writing process, which has been called "reflective argumentation".[13]

History

The philosophical origins and tradition of argument mapping

In the Elements of Logic, which was published in 1826 and issued in many subsequent editions,[14] Archbishop Richard Whately gave probably the first form of an argument map, introducing it with the suggestion that "many students probably will find it a very clear and convenient mode of exhibiting the logical analysis of the course of argument, to draw it out in the form of a Tree, or Logical Division".

However, the technique did not become widely used, possibly because for complex arguments, it involved much writing and rewriting of the premises.

Legal philosopher and theorist John Henry Wigmore produced maps of legal arguments using numbered premises in the early 20th century,[15] based in part on the ideas of 19th century philosopher Henry Sidgwick who used lines to indicate relations between terms.[16]

Anglophone argument diagramming in the 20th century

Dealing with the failure of formal reduction of informal argumentation, English speaking argumentation theory developed diagrammatic approaches to informal reasoning over a period of fifty years.

Monroe Beardsley proposed a form of argument diagram in 1950.[11] His method of marking up an argument and representing its components with linked numbers became a standard and is still widely used. He also introduced terminology that is still current describing convergent, divergent and serial arguments.

Beardsley's approach was refined by Stephen N. Thomas, whose book Practical Reasoning In Natural Language[17] introduced the term linked to describe arguments where the premises necessarily worked together to support the conclusion.[18] However, the actual distinction between dependent and independent premises had been made prior to this.[18] The introduction of the linked structure made it possible for argument maps to represent missing or "hidden" premises. In addition, Thomas suggested suggested showing reasons both for and against a conclusion with the reasons against being represented by dotted arrows.

Stephen Toulmin, in his groundbreaking and influential 1958 book The Uses of Argument,[19] identified several elements to an argument which have been generalized. The Toulmin diagram is widely used in educational critical teaching.[20][21] Toulmin introduced something that was missing from Beardsley's approach. In Beardsley, "arrows link reasons and conclusions (but) no support is given to the implication itself between them. There is no theory, in other words, of inference distinguished from logical deduction, the passage is always deemed not controversial an not subject to support and evaluation".[22] Toulmin introduced the concept of warrant which "can be considered as representing the reasons behind the inference, the backing that authorizes the link".[23]

Michael Scriven developed an argument diagram in 1976.[24] Scriven introduced counterarguments in his diagrams, which Toulmin had defined as rebuttal. Scriven also indicated missing premises with an alphabetical letter instead of a number.[25]

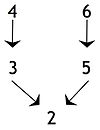

In 1988, David Kelley proposed a structured diagram technique with numbered premises, and arrows indicating inferential relations, very similar to Beardsley's earlier approach.[26] The premises were to be listed at the side of the diagram for reference. The three forms here of an argument are serial, additive (or joint), and non-additive (or convergent), respectively.

In the 1990s, Tim van Gelder and colleagues developed a series of computer software applications that permitted the premises to be fully stated and edited in the diagram, rather than in a legend.[27] Van Gelder's first program, Reason!Able, was superseded by two subsequent programs, bCisive and Rationale.[28]

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, many other software applications were developed for argument visualization. By 2013, more than 60 such software systems existed.[29] One of the differences between these software systems is whether collaboration is supported.[30] Single-user argumentation systems include Convince Me, iLogos, LARGO, Athena, Araucaria, and Carneades; small group argumentation systems include Digalo, QuestMap, Compendium, Belvedere, and AcademicTalk; community argumentation systems include Debategraph and Collaboratorium.[30] For more software examples, see: § External links.

In 1998 a series of large-scale argument maps released by Robert E. Horn stimulated widespread interest in argument mapping.[31]

Applications

Argument maps have been applied in many areas, but foremost in educational, academic and business settings, including design rationale.[32] Argument maps are also used in forensic science,[33] law, and artificial intelligence.[34] It has also been proposed that argument mapping has a great potential to improve how we understand and execute democracy, in reference to the ongoing evolution of e-democracy.[35]

Difficulties with the philosophical tradition

It has traditionally been hard to separate teaching critical thinking from the philosophical tradition of teaching logic and method, and most critical thinking textbooks have been written by philosophers. Informal logic textbooks are replete with philosophical examples, but it is unclear whether the approach in such textbooks transfers to non-philosophy students.[20] There appears to be little statistical effect after such classes. Argument mapping, however, has a measurable effect according to many studies.[36] For example, instruction in argument mapping has been shown to improve the critical thinking skills of business students.[37]

Evidence that argument mapping improves critical thinking ability

There is empirical evidence that the skills developed in argument-mapping-based critical thinking courses substantially transfer to critical thinking done without argument maps. Alvarez's meta-analysis found that such critical thinking courses produced gains of around 0.70 SD, about twice as much as standard critical-thinking courses.[38] The tests used in the reviewed studies were standard critical-thinking tests.

How argument mapping helps with critical thinking

The use of argument mapping has occurred within a number of disciplines, such as philosophy, management reporting, military and intelligence analysis, and public debates.[32]

Logical structure: Argument maps display an argument's logical structure more clearly than does the standard linear way of presenting arguments.

Critical thinking concepts: In learning to argument map, students master such key critical thinking concepts as "reason", "objection", "premise", "conclusion", "inference", "rebuttal", "unstated assumption", "co-premise", "strength of evidence", "logical structure", "independent evidence", etc. Mastering such concepts is not just a matter of memorizing their definitions or even being able to apply them correctly; it is also understanding why the distinctions these words mark are important and using that understanding to guide one's reasoning.

Visualization: Humans are highly visual and argument mapping may provide students with a basic set of visual schemas with which to understand argument structures.

More careful reading and listening: Learning to argument map teaches people to read and listen more carefully, and highlights for them the key questions "What is the logical structure of this argument?" and "How does this sentence fit into the larger structure?" In-depth cognitive processing is thus more likely.

More careful writing and speaking: Argument mapping helps people to state their reasoning and evidence more precisely, because the reasoning and evidence must fit explicitly into the map's logical structure.

Literal and intended meaning: Often, many statements in an argument do not precisely assert what the author meant. Learning to argument map enhances the complex skill of distinguishing literal from intended meaning.

Externalization: Writing something down and reviewing what one has written often helps reveal gaps and clarify one's thinking. Because the logical structure of argument maps is clearer than that of linear prose, the benefits of mapping will exceed those or ordinary writing.

Anticipating replies: Important to critical thinking is anticipating objections and considering the plausibility of different rebuttals. Mapping develops this anticipation skill, and so improves analysis.

Standards

Argument Interchange Format

The Argument Interchange Format, AIF, is an international effort to develop a representational mechanism for exchanging argument resources between research groups, tools, and domains using a semantically rich language. AIF-RDF, is the extended ontology represented in the Resource Description Framework Schema (RDFS) semantic language. Though AIF is still something of a moving target, it is settling down.[39]

See the AIF original draft description (2006) and the full AIF-RDF ontology specifications in RDFS format.

Legal Knowledge Interchange Format

The Legal Knowledge Interchange Format (LKIF), developed in the European ESTRELLA project, is an XML schema for rules and arguments, designed with the goal of becoming a standard for representing and interchanging policy, legislation and cases, including their justificatory arguments, in the legal domain. LKIF builds on and uses the Web Ontology Language (OWL) for representing concepts and includes a reusable basic ontology of legal concepts.

See also

Notes

- ^ Freeman 1991, pp. 49–90

- ^ For example: Davies 2012; Facione 2013, p. 86; Fisher 2004; Kelley 2014, p. 73; Kunsch, Schnarr & van Tyle 2014; Walton 2013, p. 10

- ^ For example: Hoffmann & Borenstein 2013; Metcalfe & Sastrowardoyo 2013; Ricky Ohl, "Computer supported argument visualisation: modelling in consultative democracy around wicked problems", in Okada, Buckingham Shum & Sherborne 2008, pp. 361–380

- ^ a b Reed & Rowe 2007, p. 64

- ^ For example: Walton 2013, pp. 18–20

- ^ Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007, p. 2

- ^ Freeman 1991, pp. 49–90; Reed & Rowe 2007

- ^ Harrell 2010, p. 19

- ^ Freeman 1991, pp. 91–110; Harrell 2010, p. 20

- ^ Beardsley 1950, pp. 18–19; Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007, pp. 3–8; Harrell 2010, pp. 19–21

- ^ a b Beardsley 1950

- ^ Harrell 2010, p. 28

- ^ For example: Hoffmann & Borenstein 2013; Hoffmann 2015

- ^ Whately 1834 (first published 1826)

- ^ Wigmore 1913

- ^ Goodwin 2000

- ^ Thomas 1997 (first published 1973)

- ^ a b Snoeck Henkemans 2000, p. 453

- ^ Toulmin 2003 (first published 1958)

- ^ a b Simon, Erduran & Osborne 2006

- ^ Böttcher & Meisert 2011; Macagno & Konstantinidou 2013

- ^ Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007, p. 8

- ^ Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007, p. 9

- ^ Scriven 1976

- ^ Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007, p. 10–11

- ^ Kelley 1988

- ^ van Gelder 2007

- ^ Berg et al. 2009

- ^ Walton 2013, p. 11

- ^ a b Scheuer et al. 2010

- ^ Holmes 1999; Horn 1998 and Robert E. Horn, "Infrastructure for navigating interdisciplinary debates: critical decisions for representing argumentation", in Kirschner, Buckingham Shum & Carr 2003, pp. 165–184

- ^ a b Kirschner, Buckingham Shum & Carr 2003; Okada, Buckingham Shum & Sherborne 2008

- ^ For example: Bex 2011

- ^ For example: Verheij 2005; Reed, Walton & Macagno 2007; Walton 2013

- ^ Hilbert 2009

- ^ Twardy 2004; Álvarez Ortiz 2007; Harrell 2008; Yanna Rider and Neil Thomason, "Cognitive and pedagogical benefits of argument mapping: LAMP guides the way to better thinking", in Okada, Buckingham Shum & Sherborne 2008, pp. 113–130; Dwyer 2011; Davies 2012

- ^ Carrington et al. 2011; Kunsch, Schnarr & van Tyle 2014

- ^ Álvarez Ortiz 2007, pp. 69–70 et seq

- ^ Bex et al. 2013

References

- Álvarez Ortiz, Claudia María (2007). Does philosophy improve critical thinking skills? (PDF) (M.A.). Department of Philosophy, University of Melbourne. OCLC 271475715.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beardsley, Monroe C. (1950). Practical logic. New York: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 4318971.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berg, Timo ter; van Gelder, Tim; Patterson, Fiona; Teppema, Sytske (2009). Critical thinking: reasoning and communicating with Rationale. Amsterdam: Pearson Education Benelux. ISBN 9043018015. OCLC 301884530.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bex, Floris J. (2011). Arguments, stories and criminal evidence: a formal hybrid theory. Law and philosophy library. Vol. 92. Dordrecht; New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0140-3. ISBN 9789400701397. OCLC 663950184.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bex, Floris J.; Modgil, Sanjay; Prakken, Henry; Reed, Chris (2013). "On logical specifications of the Argument Interchange Format" (PDF). Journal of Logic and Computation. 23 (5): 951–989. doi:10.1093/logcom/exs033.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Böttcher, Florian; Meisert, Anke (February 2011). "Argumentation in science education: a model-based framework". Science & Education. 20 (2): 103–140. doi:10.1007/s11191-010-9304-5.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carrington, Michal; Chen, Richard; Davies, Martin; Kaur, Jagjit; Neville, Benjamin (June 2011). "The effectiveness of a single intervention of computer‐aided argument mapping in a marketing and a financial accounting subject" (PDF). Higher Education Research & Development. 30 (3): 387–403. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.559197.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Martin (Summer 2012). "Computer-aided argument mapping as a tool for teaching critical thinking". International Journal of Learning and Media. 4 (3–4): 79–84. doi:10.1162/IJLM_a_00106.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dwyer, Christopher Peter (2011). The evaluation of argument mapping as a learning tool (PDF) (Ph.D.). School of Psychology, National University of Ireland, Galway. OCLC 812818648.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Facione, Peter A. (2013) [2011]. THINK critically (2nd ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 0205490980. OCLC 770694200.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fisher, Alec (2004) [1988]. The logic of real arguments (2nd ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511818455. ISBN 0521654815. OCLC 54400059.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freeman, James B. (1991). Dialectics and the macrostructure of arguments: a theory of argument structure. Berlin; New York: Foris Publications. ISBN 3110133903. OCLC 24429943.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - van Gelder, Tim (2007). "The rationale for Rationale" (PDF). Law, Probability and Risk. 6 (1–4): 23–42. doi:10.1093/lpr/mgm032.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goodwin, Jean (2000). "Wigmore's chart method". Informal Logic. 20 (3): 223–243.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrell, Maralee (December 2008). "No computer program required: even pencil-and-paper argument mapping improves critical-thinking skills" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy. 31 (4): 351–374. doi:10.5840/teachphil200831437.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrell, Maralee (August 2010). "Creating argument diagrams". academia.edu.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hilbert, Martin (April 2009). "The maturing concept of e-democracy: from e-voting and online consultations to democratic value out of jumbled online chatter" (PDF). Journal of Information Technology and Politics. 6 (2): 87–110. doi:10.1080/19331680802715242.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoffmann, Michael H. G. (November 2015). "Reflective argumentation: a cognitive function of arguing". Argumentation. doi:10.1007/s10503-015-9388-9.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoffmann, Michael H. G.; Borenstein, Jason (February 2013). "Understanding ill-structured engineering ethics problems through a collaborative learning and argument visualization approach". Science and Engineering Ethics. 20 (1): 261–276. doi:10.1007/s11948-013-9430-y. PMID 23420467.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holmes, Bob (10 July 1999). "Beyond words". New Scientist. No. 2194. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horn, Robert E. (1998). Visual language: global communication for the 21st century. Bainbridge Island, WA: MacroVU, Inc. ISBN 189263709X. OCLC 41138655.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelley, David (1988). The art of reasoning (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393959139. OCLC 16984878.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelley, David (2014) [1988]. The art of reasoning: an introduction to logic and critical thinking (4th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393930785. OCLC 849801096.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirschner, Paul Arthur; Buckingham Shum, Simon J; Carr, Chad S, eds. (2003). Visualizing argumentation: software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making. Computer supported cooperative work. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-0037-9. ISBN 1852336641. OCLC 50676911.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kunsch, David W.; Schnarr, Karin; van Tyle, Russell (November 2014). "The use of argument mapping to enhance critical thinking skills in business education". Journal of Education for Business. 89 (8): 403–410. doi:10.1080/08832323.2014.925416.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Macagno, Fabrizio; Konstantinidou, Aikaterini (August 2013). "What students' arguments can tell us: using argumentation schemes in science education". Argumentation. 27 (3): 225–243. doi:10.1007/s10503-012-9284-5.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Metcalfe, Mike; Sastrowardoyo, Saras (November 2013). "Complex project conceptualisation and argument mapping". International Journal of Project Management. 31 (8): 1129–1138. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.01.004.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Okada, Alexandra; Buckingham Shum, Simon J; Sherborne, Tony, eds. (2008). Knowledge cartography: software tools and mapping techniques. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-84800-149-7. ISBN 9781848001480. OCLC 195735592.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reed, Chris; Rowe, Glenn (2007). "A pluralist approach to argument diagramming". Law, Probability and Risk. 6 (1–4): 59–85. doi:10.1093/lpr/mgm030.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reed, Chris; Walton, Douglas; Macagno, Fabrizio (March 2007). "Argument diagramming in logic, law and artificial intelligence". The Knowledge Engineering Review. 22 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0269888907001051.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scheuer, Oliver; Loll, Frank; Pinkwart, Niels; McLaren, Bruce M. (2010). "Computer-supported argumentation: a review of the state of the art" (PDF). International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. 5 (1): 43–102. doi:10.1007/s11412-009-9080-x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scriven, Michael (1976). Reasoning. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070558825. OCLC 2800373.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simon, Shirley; Erduran, Sibel; Osborne, Jonathan (2006). "Learning to teach argumentation: research and development in the science classroom" (PDF). International Journal of Science Education. 28 (2–3): 235–260. doi:10.1080/09500690500336957.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Snoeck Henkemans, A. Francisca (November 2000). "State-of-the-art: the structure of argumentation" (PDF). Argumentation. 14 (4): 447–473. doi:10.1023/A:1007800305762.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Stephen N. (1997) [1973]. Practical reasoning in natural language (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0136782698. OCLC 34745923.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toulmin, Stephen E. (2003) [1958]. The uses of argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511840005. ISBN 0521534836. OCLC 57253830.

- Twardy, Charles R. (June 2004). "Argument maps improve critical thinking" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy. 27 (2): 95–116. doi:10.5840/teachphil200427213.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verheij, Bart (2005). Virtual arguments: on the design of argument assistants for lawyers and other arguers. Information technology & law series. Vol. 6. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press. ISBN 9789067041904. OCLC 59617214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, Douglas N. (2013). Methods of argumentation. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139600187. ISBN 1107677335. OCLC 830523850.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whately, Richard (1834) [1826]. Elements of logic: comprising the substance of the article in the Encyclopædia metropolitana: with additions, &c (5th ed.). London: B. Fellowes. OCLC 1739330.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wigmore, John Henry (1913). The principles of judicial proof: as given by logic, psychology, and general experience, and illustrated in judicial trials. Boston: Little Brown. OCLC 1938596.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Facione, Peter A.; Facione, Noreen C. (2007). Thinking and reasoning in human decision making: the method of argument and heuristic analysis. Milbrae, CA: California Academic Press. ISBN 1891557580. OCLC 182039452.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - van Gelder, Tim (17 February 2009). "What is argument mapping?". timvangelder.com. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Harrell, Maralee (June 2005). "Using argument diagramming software in the classroom" (PDF). Teaching Philosophy. 28 (2): 163–177. doi:10.5840/teachphil200528222.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Argument mapping software

- Araucaria (open source, cross platform/Java)

- Argumentative (open source, Windows); supports single-user, graphical argumentation

- Argunet (open source, cross platform)

- Compendium (open source, cross platform/Java)

- PIRIKA (PIlot for the RIght Knowledge and Argument) (open source, Linux, Windows)

Online, collaborative software

- AGORA-net (user interface in English, German, Spanish, Chinese, and Russian)

- bCisiveOnline

- Carneades (open source, argument (re)construction, evaluation, mapping and interchange)

- Collam (JavaScript library for visualizing argument maps)

- Debategraph

- TruthMapping

- Arguman (Open source, English, Turkish, and Chinese)