Chronology of computation of π: Difference between revisions

Content deleted Content added

m WP:CHECKWIKI error fix for #02. Fix br tag, Do general fixes if a problem exists. - |

Stemonitis (talk | contribs) combine & format a couple of repeated refs. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

!align="right"| Decimal places<br />([[world record]]s<br /> in '''bold''') |

!align="right"| Decimal places<br />([[world record]]s<br /> in '''bold''') |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|2000? BCЕ||[[Egyptian mathematics|Ancient Egyptians]]<ref>http://crd-legacy.lbl.gov/~dhbailey/dhbpapers/pi-quest.pdf</ref> |

|2000? BCЕ||[[Egyptian mathematics|Ancient Egyptians]]<ref name="Bailey">{{cite journal |authors=David H. Bailey, Jonathan M. Borwein, Peter B. Borwein & Simon Plouffe |year=1997 |title=The quest for pi |journal=[[Mathematical Intelligencer]] |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=50–57 |url=http://crd-legacy.lbl.gov/~dhbailey/dhbpapers/pi-quest.pdf}}</ref> |

||

|4*(8/9)^2 |

|4*(8/9)^2 |

||

|align="right"|3.16045...||1 |

|align="right"|3.16045...||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|2000? BCЕ||Ancient Babylonians<ref |

|2000? BCЕ||Ancient Babylonians<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|3+1/8||align="right"|3.125||1 |

|3+1/8||align="right"|3.125||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1200? BCЕ||China<ref |

|1200? BCЕ||China<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|||align="right"|3||1 |

|||align="right"|3||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|550? BCЕ||Bible (1 Kings 7:23)<ref |

|550? BCЕ||Bible (1 Kings 7:23)<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

||"...a molten sea, ten cubits from the one brim to the other: it was round all about,... a line of thirty cubits did compass it round about"||align="right"|3||1 |

||"...a molten sea, ten cubits from the one brim to the other: it was round all about,... a line of thirty cubits did compass it round about"||align="right"|3||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|[[compass and straightedge]]||Anaxagoras didn't offer any solution||0 |

|[[compass and straightedge]]||Anaxagoras didn't offer any solution||0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|350? BCЕ||[[Sulbasutras]]<ref>https://advancesindifferenceequations.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-100</ref><ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=DHvThPNp9yMC&lpg=PA18&ots=Aoy0T2r3Qz&dq=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&hl=de&pg=PA18#v=onepage&q=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&f=false</ref> |

|350? BCЕ||[[Sulbasutras]]<ref name="Agarwal">{{cite journal |authors=Ravi P. Agarwal, Hans Agarwal & Syamal K. Sen |year=2013 |title=Birth, growth and computation of pi to ten trillion digits |journal=[[Advances in Difference Equations]] |volume=2013 |page=100 |doi=10.1186/1687-1847-2013-100 |url=https://advancesindifferenceequations.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-100}}</ref><ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=DHvThPNp9yMC&lpg=PA18&ots=Aoy0T2r3Qz&dq=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&hl=de&pg=PA18#v=onepage&q=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&f=false</ref> |

||

|(6/(2+{{radic|2}}))^2 |

|(6/(2+{{radic|2}}))^2 |

||

|align="right"|3.088311 …||1 |

|align="right"|3.088311 …||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|c. 250 BCE||[[Archimedes]]<ref |

|c. 250 BCE||[[Archimedes]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|223/71 < {{pi}} < 22/7 |

|223/71 < {{pi}} < 22/7 |

||

|align="right"|3.140845... < {{pi}} < 3.142857...<br />3.1418 (ave.)||'''3''' |

|align="right"|3.140845... < {{pi}} < 3.142857...<br />3.1418 (ave.)||'''3''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|15 BCE||[[Vitruvius]]<ref |

|15 BCE||[[Vitruvius]]<ref name="Agarwal"/> |

||

|25/8 |

|25/8 |

||

|align="right"|3.125||1 |

|align="right"|3.125||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|5||[[Liu Xin]]<ref name="Agarwal"/> |

|||

|5||[[Liu Xin]]<ref>https://advancesindifferenceequations.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-100</ref> |

|||

|the exact method is unknown |

|the exact method is unknown |

||

|align="right"|3.1457||2 |

|align="right"|3.1457||2 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|130||[[Zhang Heng]] ([[Book of the Later Han]])<ref |

|130||[[Zhang Heng]] ([[Book of the Later Han]])<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|{{radic|10}} = 3.162277...<br />730/232 |

|{{radic|10}} = 3.162277...<br />730/232 |

||

|align="right"|3.146551...||1 |

|align="right"|3.146551...||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|150||[[Ptolemy]]<ref |

|150||[[Ptolemy]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|377/120 |

|377/120 |

||

|align="right"|3.141666...||3 |

|align="right"|3.141666...||3 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|250||[[Wang Fan]]<ref |

|250||[[Wang Fan]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|142/45 |

|142/45 |

||

|align="right"|3.155555...||1 |

|align="right"|3.155555...||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|263||[[Liu Hui's π algorithm|Liu Hui]]<ref |

|263||[[Liu Hui's π algorithm|Liu Hui]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|3.141024 < {{pi}} < 3.142074<br />3927/1250 |

|3.141024 < {{pi}} < 3.142074<br />3927/1250 |

||

|align="right"|3.14159||'''5''' |

|align="right"|3.14159||'''5''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|400||[[:zh:何承天 (南朝)|He Chengtian]]<ref |

|400||[[:zh:何承天 (南朝)|He Chengtian]]<ref name="Agarwal"/> |

||

|111035/35329 |

|111035/35329 |

||

|align="right"|3.142885...||2 |

|align="right"|3.142885...||2 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|480||[[Zu Chongzhi]]<ref |

|480||[[Zu Chongzhi]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|3.1415926 < {{pi}} < 3.1415927 <br />Zu's ratio 355/113 |

|3.1415926 < {{pi}} < 3.1415927 <br />Zu's ratio 355/113 |

||

|align="right"|3.1415926||'''7''' |

|align="right"|3.1415926||'''7''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|499||[[Aryabhata]]<ref |

|499||[[Aryabhata]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|62832/20000 |

|62832/20000 |

||

|align="right"|3.1416||4 |

|align="right"|3.1416||4 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|640||[[Brahmagupta]]<ref |

|640||[[Brahmagupta]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|{{radic|10}} |

|{{radic|10}} |

||

|align="right"|3.162277...||1 |

|align="right"|3.162277...||1 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|800||[[Al Khwarizmi]]<ref |

|800||[[Al Khwarizmi]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|3.1416||4 |

|align="right"|3.1416||4 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1150||[[Bhāskara II]]<ref |

|1150||[[Bhāskara II]]<ref name="Agarwal"/> |

||

| 3927/1250 and 754/240 |

| 3927/1250 and 754/240 |

||

|align="right"|3,1416||3 |

|align="right"|3,1416||3 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1220||[[Leonardo of Pisa|Fibonacci]]<ref |

|1220||[[Leonardo of Pisa|Fibonacci]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|3.141818||3 |

|align="right"|3.141818||3 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1320|| [[Zhao Youqin's π algorithm|Zhao Youqin]]<ref |

|1320|| [[Zhao Youqin's π algorithm|Zhao Youqin]]<ref name="Agarwal"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|3.1415926||7 |

|align="right"|3.1415926||7 |

||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

|align="right"|'''38''' <!-- calculated=39; determined=38 --> |

|align="right"|'''38''' <!-- calculated=39; determined=38 --> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1665||[[Isaac Newton]]<ref |

|1665||[[Isaac Newton]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|16 |

|align="right"|16 |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

|align="right"|11 <br />16 |

|align="right"|11 <br />16 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1699||[[Abraham Sharp]]<ref |

|1699||[[Abraham Sharp]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated pi to 72 digits, but not all were correct |

|Calculated pi to 72 digits, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|'''71''' |

|align="right"|'''71''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1706||[[John Machin]]<ref |

|1706||[[John Machin]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|'''100''' |

|align="right"|'''100''' |

||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

| |

| |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1719||[[Thomas Fantet de Lagny]]<ref |

|1719||[[Thomas Fantet de Lagny]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated 127 decimal places, but not all were correct |

|Calculated 127 decimal places, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|'''112''' |

|align="right"|'''112''' |

||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

|align="right"|'''126''' |

|align="right"|'''126''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1794||[[Jurij Vega]]<ref |

|1794||[[Jurij Vega]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated 140 decimal places, but not all were correct |

|Calculated 140 decimal places, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|'''136''' |

|align="right"|'''136''' |

||

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

|align="right"|'''152''' |

|align="right"|'''152''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1841||[[William Rutherford (mathematician)|William Rutherford]]<ref |

|1841||[[William Rutherford (mathematician)|William Rutherford]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated 208 decimal places, but not all were correct |

|Calculated 208 decimal places, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|152 |

|align="right"|152 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1844||[[Zacharias Dase]] and Strassnitzky<ref |

|1844||[[Zacharias Dase]] and Strassnitzky<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated 205 decimal places, but not all were correct |

|Calculated 205 decimal places, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|'''200''' |

|align="right"|'''200''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1847||[[Thomas Clausen (mathematician)|Thomas Clausen]]<ref |

|1847||[[Thomas Clausen (mathematician)|Thomas Clausen]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Calculated 250 decimal places, but not all were correct |

|Calculated 250 decimal places, but not all were correct |

||

|align="right"|'''248''' |

|align="right"|'''248''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1853||Lehmann<ref |

|1853||Lehmann<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

| |

| |

||

|align="right"|'''261''' |

|align="right"|'''261''' |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

|align="right"|'''500''' |

|align="right"|'''500''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1874||[[William Shanks]]<ref |

|1874||[[William Shanks]]<ref name="Bailey"/> |

||

|Took 15 years to calculate 707 decimal places, but not all were correct (the error was found by D. F. Ferguson in 1946) |

|Took 15 years to calculate 707 decimal places, but not all were correct (the error was found by D. F. Ferguson in 1946) |

||

|align="right"|'''527''' |

|align="right"|'''527''' |

||

| Line 597: | Line 597: | ||

|align="right"|'''13,300,000,000,000''' |

|align="right"|'''13,300,000,000,000''' |

||

|} |

|} |

||

==Literature== |

|||

Bailey et al. [http://crd-legacy.lbl.gov/~dhbailey/dhbpapers/pi-quest.pdf The Quest for Pi]. Mathematical Intelligencer, vol. 19, no. 1 (Jan. 1997), pg. 50–57 |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 12:07, 15 November 2016

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

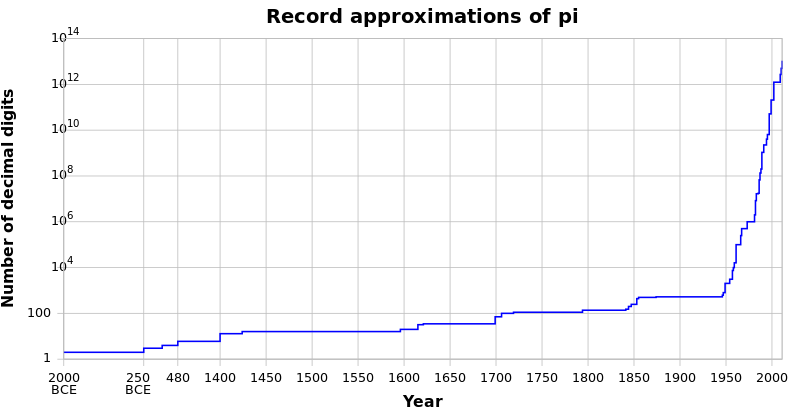

The table below is a brief chronology of computed numerical values of, or bounds on, the mathematical constant pi (π). For more detailed explanations for some of these calculations, see Approximations of π.

Before 1400

| Date | Whom | Formulation | Value of pi | Decimal places (world records in bold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000? BCЕ | Ancient Egyptians[1] | 4*(8/9)^2 | 3.16045... | 1 |

| 2000? BCЕ | Ancient Babylonians[1] | 3+1/8 | 3.125 | 1 |

| 1200? BCЕ | China[1] | 3 | 1 | |

| 550? BCЕ | Bible (1 Kings 7:23)[1] | "...a molten sea, ten cubits from the one brim to the other: it was round all about,... a line of thirty cubits did compass it round about" | 3 | 1 |

| 434 BCE | Anaxagoras attempted to square the circle[2] | compass and straightedge | Anaxagoras didn't offer any solution | 0 |

| 350? BCЕ | Sulbasutras[3][4] | (6/(2+√2))^2 | 3.088311 … | 1 |

| c. 250 BCE | Archimedes[1] | 223/71 < π < 22/7 | 3.140845... < π < 3.142857... 3.1418 (ave.) |

3 |

| 15 BCE | Vitruvius[3] | 25/8 | 3.125 | 1 |

| 5 | Liu Xin[3] | the exact method is unknown | 3.1457 | 2 |

| 130 | Zhang Heng (Book of the Later Han)[1] | √10 = 3.162277... 730/232 |

3.146551... | 1 |

| 150 | Ptolemy[1] | 377/120 | 3.141666... | 3 |

| 250 | Wang Fan[1] | 142/45 | 3.155555... | 1 |

| 263 | Liu Hui[1] | 3.141024 < π < 3.142074 3927/1250 |

3.14159 | 5 |

| 400 | He Chengtian[3] | 111035/35329 | 3.142885... | 2 |

| 480 | Zu Chongzhi[1] | 3.1415926 < π < 3.1415927 Zu's ratio 355/113 |

3.1415926 | 7 |

| 499 | Aryabhata[1] | 62832/20000 | 3.1416 | 4 |

| 640 | Brahmagupta[1] | √10 | 3.162277... | 1 |

| 800 | Al Khwarizmi[1] | 3.1416 | 4 | |

| 1150 | Bhāskara II[3] | 3927/1250 and 754/240 | 3,1416 | 3 |

| 1220 | Fibonacci[1] | 3.141818 | 3 | |

| 1320 | Zhao Youqin[3] | 3.1415926 | 7 |

From 1400 onwards

| Date | Whom | Note | Decimal places (world records in bold) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All records from 1400 onwards are given as the number of correct decimal places. | |||

| 1400 | Madhava of Sangamagrama | Probably discovered the infinite power series expansion of π, now known as the Leibniz formula for pi[5] |

10 |

| 1424 | Jamshīd al-Kāshī[6] | 17 | |

| 1573 | Valentinus Otho | 355/113 | 6 |

| 1579 | François Viète[7] | 9 | |

| 1593 | Adriaan van Roomen[8] | 15 | |

| 1596 | Ludolph van Ceulen | 20 | |

| 1615 | 32 | ||

| 1621 | Willebrord Snell (Snellius) | Pupil of Van Ceulen | 35 |

| 1630 | Christoph Grienberger[9][10] | 38 | |

| 1665 | Isaac Newton[1] | 16 | |

| 1681 | Takakazu Seki[11] | 11 16 | |

| 1699 | Abraham Sharp[1] | Calculated pi to 72 digits, but not all were correct | 71 |

| 1706 | John Machin[1] | 100 | |

| 1706 | William Jones | Introduced the Greek letter 'π' | |

| 1719 | Thomas Fantet de Lagny[1] | Calculated 127 decimal places, but not all were correct | 112 |

| 1722 | Toshikiyo Kamata | 24 | |

| 1722 | Katahiro Takebe | 41 | |

| 1739 | Yoshisuke Matsunaga | 51 | |

| 1748 | Leonhard Euler | Used the Greek letter 'π' in his book Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum and assured its popularity. | |

| 1761 | Johann Heinrich Lambert | Proved that π is irrational | |

| 1775 | Euler | Pointed out the possibility that π might be transcendental | |

| 1789 | Jurij Vega | Calculated 143 decimal places, but not all were correct | 126 |

| 1794 | Jurij Vega[1] | Calculated 140 decimal places, but not all were correct | 136 |

| 1794 | Adrien-Marie Legendre | Showed that π² (and hence π) is irrational, and mentioned the possibility that π might be transcendental. | |

| Late 18th century | Anonymous manuscript | Turns up at Radcliffe Library, in Oxford, England, discovered by F. X. von Zach, giving the value of pi to 154 digits, 152 of which were correct | 152 |

| 1841 | William Rutherford[1] | Calculated 208 decimal places, but not all were correct | 152 |

| 1844 | Zacharias Dase and Strassnitzky[1] | Calculated 205 decimal places, but not all were correct | 200 |

| 1847 | Thomas Clausen[1] | Calculated 250 decimal places, but not all were correct | 248 |

| 1853 | Lehmann[1] | 261 | |

| 1855 | Richter | 500 | |

| 1874 | William Shanks[1] | Took 15 years to calculate 707 decimal places, but not all were correct (the error was found by D. F. Ferguson in 1946) | 527 |

| 1882 | Ferdinand von Lindemann | Proved that π is transcendental (the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem) | |

| 1897 | The U.S. state of Indiana | Came close to legislating the value 3.2 (among others) for π. House Bill No. 246 passed unanimously. The bill stalled in the state Senate due to a suggestion of possible commercial motives involving publication of a textbook.[12] | 1 |

| 1910 | Srinivasa Ramanujan | Found several rapidly converging infinite series of π, which can compute 8 decimal places of π with each term in the series. Since the 1980s, his series have become the basis for the fastest algorithms currently used by Yasumasa Kanada and the Chudnovsky brothers to compute π. | |

| 1946 | D. F. Ferguson | Desk calculator | 620 |

| 1947 | Ivan Niven | Gave a very elementary proof that π is irrational | |

| January 1947 | D. F. Ferguson | Desk calculator | 710 |

| September 1947 | D. F. Ferguson | Desk calculator | 808 |

| 1949 | D. F. Ferguson and John Wrench | Desk calculator | 1,120 |

The age of electronic computers (from 1949 onwards)

| Date | Whom | Implementation | Time | Decimal places (world records in bold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All records from 1949 onwards were calculated with electronic computers. | ||||

| 1949 | John Wrench, and L. R. Smith | Were the first to use an electronic computer (the ENIAC) to calculate π (also attributed to Reitwiesner et al.) [13] | 70 hours | 2,037 |

| 1953 | Kurt Mahler | Showed that π is not a Liouville number | ||

| 1954 | S. C. Nicholson & J. Jeenel | Using the NORC [14] | 13 minutes | 3,093 |

| 1957 | George E. Felton | Ferranti Pegasus computer (London), calculated 10,021 digits, but not all were correct [15] | 7,480 | |

| January 1958 | Francois Genuys | IBM 704 [16] | 1.7 hours | 10,000 |

| May 1958 | George E. Felton | Pegasus computer (London) | 33 hours | 10,021 |

| 1959 | Francois Genuys | IBM 704 (Paris)[17] | 4.3 hours | 16,167 |

| 1961 | Daniel Shanks and John Wrench | IBM 7090 (New York)[18] | 8.7 hours | 100,265 |

| 1961 | J.M. Gerard | IBM 7090 (London) | 39 minutes | 20,000 |

| 1966 | Jean Guilloud and J. Filliatre | IBM 7030 (Paris) | 28 hours {?) | 250,000 |

| 1967 | Jean Guilloud and M. Dichampt | CDC 6600 (Paris) | 28 hours | 500,000 |

| 1973 | Jean Guilloud and Martin Bouyer | CDC 7600 | 23.3 hours | 1,001,250 |

| 1981 | Kazunori Miyoshi and Yasumasa Kanada | FACOM M-200 | 2,000,036 | |

| 1981 | Jean Guilloud | Not known | 2,000,050 | |

| 1982 | Yoshiaki Tamura | MELCOM 900II | 2,097,144 | |

| 1982 | Yoshiaki Tamura and Yasumasa Kanada | HITAC M-280H | 2.9 hours | 4,194,288 |

| 1982 | Yoshiaki Tamura and Yasumasa Kanada | HITAC M-280H | 8,388,576 | |

| 1983 | Yasumasa Kanada, Sayaka Yoshino and Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC M-280H | 16,777,206 | |

| October 1983 | Yasunori Ushiro and Yasumasa Kanada | HITAC S-810/20 | 10,013,395 | |

| October 1985 | Bill Gosper | Symbolics 3670 | 17,526,200 | |

| January 1986 | David H. Bailey | CRAY-2 | 29,360,111 | |

| September 1986 | Yasumasa Kanada, Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC S-810/20 | 33,554,414 | |

| October 1986 | Yasumasa Kanada, Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC S-810/20 | 67,108,839 | |

| January 1987 | Yasumasa Kanada, Yoshiaki Tamura, Yoshinobu Kubo and others | NEC SX-2 | 134,214,700 | |

| January 1988 | Yasumasa Kanada and Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC S-820/80 | 201,326,551 | |

| May 1989 | Gregory V. Chudnovsky & David V. Chudnovsky | CRAY-2 & IBM 3090/VF | 480,000,000 | |

| June 1989 | Gregory V. Chudnovsky & David V. Chudnovsky | IBM 3090 | 535,339,270 | |

| July 1989 | Yasumasa Kanada and Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC S-820/80 | 536,870,898 | |

| August 1989 | Gregory V. Chudnovsky & David V. Chudnovsky | IBM 3090 | 1,011,196,691 | |

| 19 November 1989 | Yasumasa Kanada and Yoshiaki Tamura | HITAC S-820/80 | 1,073,740,799 | |

| August 1991 | Gregory V. Chudnovsky & David V. Chudnovsky | Homemade parallel computer (details unknown, not verified) [19] | 2,260,000,000 | |

| 18 May 1994 | Gregory V. Chudnovsky & David V. Chudnovsky | New homemade parallel computer (details unknown, not verified) | 4,044,000,000 | |

| 26 June 1995 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITAC S-3800/480 (dual CPU) [20] | 3,221,220,000 | |

| 1995 | Simon Plouffe | Finds a formula that allows the nth digit of pi to be calculated without calculating the preceding digits. | ||

| 28 August 1995 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITAC S-3800/480 (dual CPU) [21] | 4,294,960,000 | |

| 11 October 1995 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITAC S-3800/480 (dual CPU) [22] | 6,442,450,000 | |

| 6 July 1997 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITACHI SR2201 (1024 CPU) [23] | 51,539,600,000 | |

| 5 April 1999 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITACHI SR8000 (64 of 128 nodes) [24] | 68,719,470,000 | |

| 20 September 1999 | Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi | HITACHI SR8000/MPP (128 nodes) [25] | 206,158,430,000 | |

| 24 November 2002 | Yasumasa Kanada & 9 man team | HITACHI SR8000/MPP (64 nodes), Department of Information Science at the University of Tokyo in Tokyo, Japan [26] | 600 hours | 1,241,100,000,000 |

| 29 April 2009 | Daisuke Takahashi et al. | T2K Open Supercomputer (640 nodes), single node speed is 147.2 gigaflops, computer memory is 13.5 terabytes, Gauss–Legendre algorithm, Center for Computational Sciences at the University of Tsukuba in Tsukuba, Japan[27] | 29.09 hours | 2,576,980,377,524 |

| Date | Whom | Implementation | Time | Decimal places (world records in bold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All records from Dec 2009 onwards are calculated on home computers with commercially available parts. | ||||

| 31 December 2009 | Fabrice Bellard |

|

131 days | 2,699,999,990,000 |

| 2 August 2010 | Shigeru Kondo[30] |

|

90 days | 5,000,000,000,000 |

| 17 October 2011 | Shigeru Kondo[33] |

|

371 days | 10,000,000,000,050 |

| 28 December 2013 | Shigeru Kondo[34] |

|

94 days | 12,100,000,000,050 |

| 8 October 2014 | "houkouonchi"[35] |

|

208 days | 13,300,000,000,000 |

See also

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant π |

|---|

| 3.1415926535897932384626433... |

| Uses |

| Properties |

| Value |

| People |

| History |

| In culture |

| Related topics |

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "The quest for pi" (PDF). Mathematical Intelligencer. 19 (1): 50–57. 1997.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ https://www.math.rutgers.edu/~cherlin/History/Papers2000/wilson.html

- ^ a b c d e f "Birth, growth and computation of pi to ten trillion digits". Advances in Difference Equations. 2013: 100. 2013. doi:10.1186/1687-1847-2013-100.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=DHvThPNp9yMC&lpg=PA18&ots=Aoy0T2r3Qz&dq=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&hl=de&pg=PA18#v=onepage&q=Shulba%20Sutras%20date%20of%20creation&f=false

- ^ Bag, A. K. (1980). "Indian Literature on Mathematics During 1400–1800 A.D." (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 15 (1): 86.

π ≈ 2,827,433,388,233/9×10−11 = 3.14159 26535 92222…, good to 10 decimal places.

- ^ approximated 2π to 9 sexagesimal digits. Al-Kashi, author: Adolf P. Youschkevitch, chief editor: Boris A. Rosenfeld, p. 256 O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid Mas'ud al-Kashi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews. Azarian, Mohammad K. (2010), "al-Risāla al-muhītīyya: A Summary", Missouri Journal of Mathematical Sciences 22 (2): 64–85.

- ^ Viète, François (1579). Canon mathematicus seu ad triangula : cum adpendicibus (in Latin).

- ^ Romanus, Adrianus (1593). Ideae mathematicae pars prima, sive methodus polygonorum (in Latin).

- ^ Grienbergerus, Christophorus (1630). Elementa Trigonometrica (PDF) (in Latin).

- ^ Hobson, Ernest William (1913). "Squaring the Circle": a History of the Problem (PDF). p. 27.

- ^ Yoshio, Mikami; Eugene Smith, David (April 2004) [January 1914]. A History of Japanese Mathematics (paperback ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43482-6.

- ^ Lopez-Ortiz, Alex (February 20, 1998). "Indiana Bill sets value of Pi to 3". the news.answers WWW archive. Department of Information and Computing Sciences, Utrecht University. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ^ G. Reitwiesner, "An ENIAC determination of Pi and e to more than 2000 decimal places," MTAC, v. 4, 1950, pp. 11–15"

- ^ S. C, Nicholson & J. Jeenel, "Some comments on a NORC computation of x," MTAC, v. 9, 1955, pp. 162–164

- ^ G. E. Felton, "Electronic computers and mathematicians," Abbreviated Proceedings of the Oxford Mathematical Conference for Schoolteachers and Industrialists at Trinity College, Oxford, April 8–18, 1957, pp. 12–17, footnote pp. 12–53. This published result is correct to only 7480D, as was established by Felton in a second calculation, using formula (5), completed in 1958 but apparently unpublished. For a detailed account of calculations of x see J. W. Wrench, Jr., "The evolution of extended decimal approximations to x," The Mathematics Teacher, v. 53, 1960, pp. 644–650

- ^ F. Genuys, "Dix milles decimales de x," Chiffres, v. 1, 1958, pp. 17–22.

- ^ This unpublished value of x to 16167D was computed on an IBM 704 system at the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique in Paris, by means of the program of Genuys

- ^ [1] "Calculation of Pi to 100,000 Decimals" in the journal Mathematics of Computation, vol 16 (1962), issue 77, pages 76–99.

- ^ Bigger slices of Pi (determination of the numerical value of pi reaches 2.16 billion decimal digits) Science News 24 August 1991 http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-11235156.html

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_last_record_3b

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_last_record_4b

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_last_record_6b

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_last_record_51b

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_last_record_68b

- ^ ftp://pi.super-computing.org/README.our_latest_record_206b

- ^ http://www.super-computing.org/pi_current.html

- ^ http://www.hpcs.is.tsukuba.ac.jp/~daisuke/pi.html

- ^ "Fabrice Bellard's Home Page". bellard.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ http://bellard.org/pi/pi2700e9/pipcrecord.pdf

- ^ "PI-world". calico.jp. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "y-cruncher - A Multi-Threaded Pi Program". numberworld.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Pi - 5 Trillion Digits". numberworld.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Pi - 10 Trillion Digits". numberworld.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Pi - 12.1 Trillion Digits". numberworld.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "y-cruncher - A Multi-Threaded Pi Program". numberworld.org. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

External links

- Borwein, Jonathan, "The Life of Pi"

- Kanada Laboratory home page

- Stu's Pi page

- Takahashi's page