Joint dislocation: Difference between revisions

addition of statistics |

research on treatment for glenohumeral instability |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

===After care=== |

===After care=== |

||

After a dislocation, injured joints are usually held in place by a [[Splint (medicine)|splint]] (for straight joints like fingers and toes) or a [[bandage]] (for complex joints like shoulders). Additionally, the joint muscles, tendons and ligaments must also be strengthened. This is usually done through a course of [[physiotherapy]], which will also help reduce the chances of repeated dislocations of the same joint.<ref>Itoi, E., Hatakeyama, Y., Kido, T., Sato, T., Minagawa, H., Wakabayashi, I., Kobayashi, M. (2003). Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 12(5): 413-415.</ref> |

After a dislocation, injured joints are usually held in place by a [[Splint (medicine)|splint]] (for straight joints like fingers and toes) or a [[bandage]] (for complex joints like shoulders). Additionally, the joint muscles, tendons and ligaments must also be strengthened. This is usually done through a course of [[physiotherapy]], which will also help reduce the chances of repeated dislocations of the same joint.<ref>Itoi, E., Hatakeyama, Y., Kido, T., Sato, T., Minagawa, H., Wakabayashi, I., Kobayashi, M. (2003). Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 12(5): 413-415.</ref> |

||

For glenohumeral instability, the therapeutic program depends on specific characteristics of the instability pattern, severity, recurrence and direction with adaptations made based on the needs of the patient. In general, the therapeutic program should focus on restoration of strength, normalization of range of motion and optimization of flexibility and muscular performance. Throughout all stages of the rehabilitation program, it is important to take all related joints and structures into consideration. <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cools|first=Ann M.|last2=Borms|first2=Dorien|last3=Castelein|first3=Birgit|last4=Vanderstukken|first4=Fran|last5=Johansson|first5=Fredrik R.|date=2016-02-01|title=Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00167-015-3940-x|journal=Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy|language=en|volume=24|issue=2|pages=382–389|doi=10.1007/s00167-015-3940-x|issn=0942-2056}}</ref> |

|||

==Epidemiology== |

==Epidemiology== |

||

| Line 67: | Line 69: | ||

** In the United States, men are most likely to sustain a finger dislocation with an incidence rate of 17.8 per 100,000 person-years. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Golan|first=Elan|last2=Kang|first2=Kevin K.|last3=Culbertson|first3=Maya|last4=Choueka|first4=Jack|title=The Epidemiology of Finger Dislocations Presenting for Emergency Care Within the United States|url=http://han.sagepub.com/lookup/doi/10.1177/1558944715627232|journal=HAND|doi=10.1177/1558944715627232|pmc=4920528|pmid=27390562}}</ref> Women have an incidence rate of 4.65 per 100,000 person-years. <ref name=":0" />The average age group that sustain a finger dislocation are between 15 to 19 years old.<ref name=":0" /> |

** In the United States, men are most likely to sustain a finger dislocation with an incidence rate of 17.8 per 100,000 person-years. <ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Golan|first=Elan|last2=Kang|first2=Kevin K.|last3=Culbertson|first3=Maya|last4=Choueka|first4=Jack|title=The Epidemiology of Finger Dislocations Presenting for Emergency Care Within the United States|url=http://han.sagepub.com/lookup/doi/10.1177/1558944715627232|journal=HAND|doi=10.1177/1558944715627232|pmc=4920528|pmid=27390562}}</ref> Women have an incidence rate of 4.65 per 100,000 person-years. <ref name=":0" />The average age group that sustain a finger dislocation are between 15 to 19 years old.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

* [[Hip]]: Posterior and anterior [[dislocation of hip]] |

* [[Hip]]: Posterior and anterior [[dislocation of hip]] |

||

** Anterior dislocations are less common than posterior dislocations. 10% of all dislocations are anterior and this is broken down into superior and inferior types. <ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Clegg|first=Travis E.|last2=Roberts|first2=Craig S.|last3=Greene|first3=Joseph W.|last4=Prather|first4=Brad A.|title=Hip dislocations—Epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020138309004392|journal=Injury|volume=41|issue=4|pages=329–334|doi=10.1016/j.injury.2009.08.007}}</ref> Superior dislocations account for 10% of all anterior dislocations, and inferior dislocations account for 90%. <ref name=":1" /> 16-40 year old males are more likely to receive dislocations due to a car accident. <ref name=":1" /> When an individual receives a hip dislocation, there is an incidence rate of 95% that they will receive an injury to another part of their body as well. <ref name=":1" /> |

** Anterior dislocations are less common than posterior dislocations. 10% of all dislocations are anterior and this is broken down into superior and inferior types. <ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Clegg|first=Travis E.|last2=Roberts|first2=Craig S.|last3=Greene|first3=Joseph W.|last4=Prather|first4=Brad A.|title=Hip dislocations—Epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020138309004392|journal=Injury|volume=41|issue=4|pages=329–334|doi=10.1016/j.injury.2009.08.007}}</ref> Superior dislocations account for 10% of all anterior dislocations, and inferior dislocations account for 90%. <ref name=":1" /> 16-40 year old males are more likely to receive dislocations due to a car accident. <ref name=":1" /> When an individual receives a hip dislocation, there is an incidence rate of 95% that they will receive an injury to another part of their body as well. <ref name=":1" /> 46-84% of hip dislocations occur secondary to traffic accidents, the remaining percentage is due based on falls, industrial accidents or sporting injury. <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Olds|first=M.|last2=Ellis|first2=R.|last3=Donaldson|first3=K.|last4=Parmar|first4=P.|last5=Kersten|first5=P.|date=2015-07-01|title=Risk factors which predispose first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations to recurrent instability in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis|url=http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/14/913|journal=Br J Sports Med|language=en|volume=49|issue=14|pages=913–922|doi=10.1136/bjsports-2014-094342|issn=0306-3674|pmc=PMC4687692|pmid=25900943}}</ref> |

||

* Foot and Ankle: [[Lisfranc injury]] |

* Foot and Ankle: [[Lisfranc injury]] |

||

** Ankle Sprains primarily occur as a result of tearing the ATFL (anterior talofibular ligament) in the Talocrural Joint. The ATFL tears most easily when the foot is in plantarflexion and inversion.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ringleb|first=Stacie I.|last2=Dhakal|first2=Ajaya|last3=Anderson|first3=Claude D.|last4=Bawab|first4=Sebastain|last5=Paranjape|first5=Rajesh|date=2011-10-01|title=Effects of lateral ligament sectioning on the stability of the ankle and subtalar joint|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jor.21407/abstract|journal=Journal of Orthopaedic Research|language=en|volume=29|issue=10|pages=1459–1464|doi=10.1002/jor.21407|issn=1554-527X}}</ref> |

** Ankle Sprains primarily occur as a result of tearing the ATFL (anterior talofibular ligament) in the Talocrural Joint. The ATFL tears most easily when the foot is in plantarflexion and inversion.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ringleb|first=Stacie I.|last2=Dhakal|first2=Ajaya|last3=Anderson|first3=Claude D.|last4=Bawab|first4=Sebastain|last5=Paranjape|first5=Rajesh|date=2011-10-01|title=Effects of lateral ligament sectioning on the stability of the ankle and subtalar joint|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jor.21407/abstract|journal=Journal of Orthopaedic Research|language=en|volume=29|issue=10|pages=1459–1464|doi=10.1002/jor.21407|issn=1554-527X}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:52, 4 April 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2012) |

| Joint dislocation | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Latin: luxatio |

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery |

A joint dislocation, also called luxation, occurs when there is an abnormal separation in the joint, where two or more bones meet.[1] A partial dislocation is referred to as a subluxation. Dislocations are often caused by sudden trauma on the joint like an impact or fall. A joint dislocation can cause damage to the surrounding ligaments, tendons, muscles, and nerves.[2] Dislocations can occur in any joint major (shoulder, knees, etc.) or minor (toes, fingers, etc.). The most common joint dislocation is a shoulder dislocation.[1]

Treatment for joint dislocation is usually by closed reduction, that is, skilled manipulation to return the bones to their normal position. Reduction should be done only by trained people, because it can cause injury to soft tissue around the dislocation.

Causes

Joint dislocations are caused by trauma to the joint or when an individual falls on a specific joint.[3] Great and sudden force applied, by either a blow or fall, to the joint can cause the bones in the joint to be displaced or dislocated from normal position.[4] With each dislocation, the ligaments keeping the bones fixed in the correct position can be damaged or loosened, making it easier for the joint to be dislocated in the future.[5]

Some individuals are prone to dislocations due to congenital conditions, such as hypermobility syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Hypermobility syndrome is genetically inherited disorder that is thought to affect the encoding of the connective tissue protein’s collagen in the ligament of joints.[6] The loosened or stretched ligaments in the joint provide little stability and allow for the joint to be easily dislocated.[1]

Symptoms

The following symptoms are common with any type of dislocation.[1]

- Intense Pain

- Joint instability

- Deformity of the joint area

- Reduced muscle strength

- Bruising or redness of joint area

- Difficulty moving joint

- Stiffness

Treatment

A dislocated joint usually can be successfully reduced into its normal position only by a trained medical professional. Trying to reduce a joint without any training could substantially worsen the injury.[7]

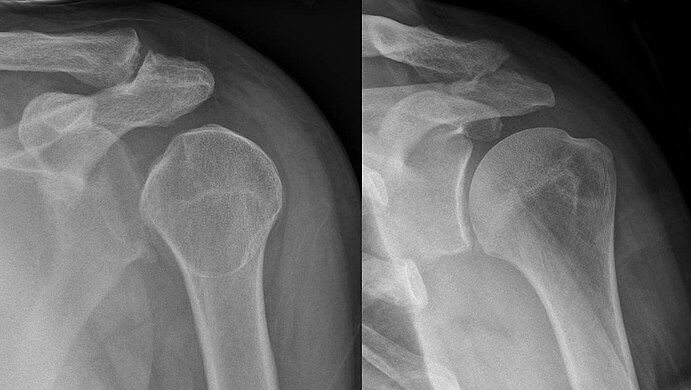

X-rays are usually taken to confirm a diagnosis and detect any fractures which may also have occurred at the time of dislocation. A dislocation is easily seen on an X-ray.[8]

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, the joint is usually manipulated back into position. This can be a very painful process, therefore this is typically done either in the emergency department under sedation or in an operating room under a general anaesthetic.[9]

It is important the joint is reduced as soon as possible, as in the state of dislocation, the blood supply to the joint (or distal anatomy) may be compromised. This is especially true in the case of a dislocated ankle, due to the anatomy of the blood supply to the foot.[10]

Shoulder injuries can also be surgically stabilized, depending on the severity, using arthroscopic surgery.[8] The most common treatment method for a dislocation of the Glenohumeral Joint (GH Joint/Shoulder Joint) is exercise based management.[11] Another method of treatment is to place the injured arm in a sling or in another immobilizing device in order to keep the joint stable. [12]

Some joints are more at risk of becoming dislocated again after an initial injury. This is due to the weakening of the muscles and ligaments which hold the joint in place. The shoulder is a prime example of this. Any shoulder dislocation should be followed up with thorough physiotherapy.[8]

On field reduction is crucial for joint dislocations. As they are extremely common in sports events, managing them correctly at the game at the time of injury, can reduce long term issues. They require prompt evaluation, diagnosis, reduction, and postreduction management before the person can be evaluated at a medical facility. [13]

After care

After a dislocation, injured joints are usually held in place by a splint (for straight joints like fingers and toes) or a bandage (for complex joints like shoulders). Additionally, the joint muscles, tendons and ligaments must also be strengthened. This is usually done through a course of physiotherapy, which will also help reduce the chances of repeated dislocations of the same joint.[14]

For glenohumeral instability, the therapeutic program depends on specific characteristics of the instability pattern, severity, recurrence and direction with adaptations made based on the needs of the patient. In general, the therapeutic program should focus on restoration of strength, normalization of range of motion and optimization of flexibility and muscular performance. Throughout all stages of the rehabilitation program, it is important to take all related joints and structures into consideration. [15]

Epidemiology

- Each joint in the body can be dislocated, however, there are common sites where most dislocations occur. The following structures are the most common sites of joint dislocations:

- Dislocated shoulder

- Shoulder dislocations account for 45% of all dislocation visits to the emergency room.[16] Anterior shoulder dislocation, the most common type of shoulder dislocation (96-98% of the time) occurs when the arm is in external rotation and abduction (away from the body) produces a force that displaces the humeral head anteriorly and downwardly. [17]Vessel and nerve injuries during a shoulder dislocation is rare, but can cause many impairments and requires a longer recovery process. [18] There is a 39% average rate of recurrence of anterior shoulder dislocation, with age, sex, hyperlaxity and greater tuberosity fractures being the key risk factors. [19]

- Knee: Patellar dislocation

- Many different knee injuries can happen. Three percent of knee injuries are acute traumatic patellar dislocations.[20] Because dislocations make the knee unstable, 15% of patellas will re-dislocate. [21]

- Patellar dislocations occur when the knee is in full extension and sustains a trauma from the lateral to medial side.[22]

- Elbow: Posterior dislocation, 90% of all elbow dislocations[23]

- Wrist: Lunate and Perilunate dislocation most common[24]

- Finger: Interphalangeal (IP) or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint dislocations[25]

- Hip: Posterior and anterior dislocation of hip

- Anterior dislocations are less common than posterior dislocations. 10% of all dislocations are anterior and this is broken down into superior and inferior types. [27] Superior dislocations account for 10% of all anterior dislocations, and inferior dislocations account for 90%. [27] 16-40 year old males are more likely to receive dislocations due to a car accident. [27] When an individual receives a hip dislocation, there is an incidence rate of 95% that they will receive an injury to another part of their body as well. [27] 46-84% of hip dislocations occur secondary to traffic accidents, the remaining percentage is due based on falls, industrial accidents or sporting injury. [28]

- Foot and Ankle: Lisfranc injury

- Ankle Sprains primarily occur as a result of tearing the ATFL (anterior talofibular ligament) in the Talocrural Joint. The ATFL tears most easily when the foot is in plantarflexion and inversion.[29]

Gallery

-

Dislocation of the left index finger

-

Radiograph of right fifth phalanx bone dislocation

-

Radiograph of left index finger dislocation

-

Depiction of reduction of a dislocated spine, ca. 1300

-

Dislocation of the carpo-metacarpal joint.

-

Radiograph of right fifth phalanx dislocation resulting from bicycle accident

-

Right fifth phalanx dislocation resulting from bicycle accident

-

Shoulder dislocation

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Dislocations. Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford. Retrieved 3/3/2013. [1]

- ^ Smith, R. L., & Brunolli, J. J. (1990). Shoulder kinesthesia after anterior glenohumeral joint dislocation. Journal Of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 11(11), 507-513.

- ^ Mayo Clinic: Finger Dislocation Joint Reduction

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine - Dislocation

- ^ Pubmed Health: Dislocation – Joint dislocation

- ^ Ruemper, A. & Watkins, K. (2012). Correlations between general joint hypermobility and joint hypermobility syndrome and injury in contemporary dance students. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 16(4): 161-166.

- ^ Bankart, A. (2004). The pathology and treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder-joint. Acta Orthop Belg. 70: 515-519

- ^ a b c Dias, J., Steingold, R., Richardson, R., Tesfayohannes, B., Gregg, P. (1987). The conservative treatment of acromioclavicular dislocation. British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery. 69(5): 719-722.

- ^ Holdsworth, F. (1970). Fractures, dislocations, and fracture dislocations of the spine. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 52 (8): 1534-1551.

- ^ Ganz, R., Gill, T., Gautier, E., Ganz, K., Krugel, N., Berlemann, U. (2001). Surgical dislocation of the adult hip. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 83(8): 1119-1124.

- ^ Warby, Sarah A.; Pizzari, Tania; Ford, Jon J.; Hahne, Andrew J.; Watson, Lyn (2014-01-01). "The effect of exercise-based management for multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review". Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 23 (1): 128–142. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.006.

- ^ Skelley, Nathan W.; McCormick, Jeremy J.; Smith, Matthew V. (2017-04-04). "In-game Management of Common Joint Dislocations". Sports Health. 6 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1177/1941738113499721. ISSN 1941-7381. PMC 4000468. PMID 24790695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Skelley, Nathan W.; McCormick, Jeremy J.; Smith, Matthew V. (2017-04-04). "In-game Management of Common Joint Dislocations". Sports Health. 6 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1177/1941738113499721. ISSN 1941-7381. PMC 4000468. PMID 24790695.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Itoi, E., Hatakeyama, Y., Kido, T., Sato, T., Minagawa, H., Wakabayashi, I., Kobayashi, M. (2003). Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 12(5): 413-415.

- ^ Cools, Ann M.; Borms, Dorien; Castelein, Birgit; Vanderstukken, Fran; Johansson, Fredrik R. (2016-02-01). "Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 24 (2): 382–389. doi:10.1007/s00167-015-3940-x. ISSN 0942-2056.

- ^ Khiami, F.; Gérometta, A.; Loriaut, P. "Management of recent first-time anterior shoulder dislocations". Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 101 (1): S51–S57. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.027.

- ^ Khiami, F.; Gérometta, A.; Loriaut, P. "Management of recent first-time anterior shoulder dislocations". Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 101 (1): S51–S57. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.027.

- ^ Khiami, F.; Gérometta, A.; Loriaut, P. "Management of recent first-time anterior shoulder dislocations". Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 101 (1): S51–S57. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.027.

- ^ Olds, M.; Ellis, R.; Donaldson, K.; Parmar, P.; Kersten, P. (2015-07-01). "Risk factors which predispose first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations to recurrent instability in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Br J Sports Med. 49 (14): 913–922. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094342. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 4687692. PMID 25900943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Hsiao, Mark; Owens, Brett D.; Burks, Robert; Sturdivant, Rodney X.; Cameron, Kenneth L. (2010-10-01). "Incidence of Acute Traumatic Patellar Dislocation Among Active-Duty United States Military Service Members". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (10): 1997–2004. doi:10.1177/0363546510371423. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 20616375.

- ^ Fithian, Donald C.; Paxton, Elizabeth W.; Stone, Mary Lou; Silva, Patricia; Davis, Daniel K.; Elias, David A.; White, Lawrence M. (2004-07-01). "Epidemiology and Natural History of Acute Patellar Dislocation". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (5): 1114–1121. doi:10.1177/0363546503260788. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 15262631.

- ^ Ramponi, Denise. "Patellar Dislocations and Reduction Procedure". Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 38 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1097/tme.0000000000000104.

- ^ Elbow Dislocation

- ^ Carpal dislocations

- ^ Finger Dislocation Joint Reduction

- ^ a b c Golan, Elan; Kang, Kevin K.; Culbertson, Maya; Choueka, Jack. "The Epidemiology of Finger Dislocations Presenting for Emergency Care Within the United States". HAND. doi:10.1177/1558944715627232. PMC 4920528. PMID 27390562.

- ^ a b c d Clegg, Travis E.; Roberts, Craig S.; Greene, Joseph W.; Prather, Brad A. "Hip dislocations—Epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes". Injury. 41 (4): 329–334. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.08.007.

- ^ Olds, M.; Ellis, R.; Donaldson, K.; Parmar, P.; Kersten, P. (2015-07-01). "Risk factors which predispose first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations to recurrent instability in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Br J Sports Med. 49 (14): 913–922. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094342. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 4687692. PMID 25900943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Ringleb, Stacie I.; Dhakal, Ajaya; Anderson, Claude D.; Bawab, Sebastain; Paranjape, Rajesh (2011-10-01). "Effects of lateral ligament sectioning on the stability of the ankle and subtalar joint". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 29 (10): 1459–1464. doi:10.1002/jor.21407. ISSN 1554-527X.