Biology and political orientation: Difference between revisions

Finnusertop (talk | contribs) Expanded lead: wholly based on cited content in the body of the article; in body: wls and one archive url |

Updated the Brain studies section to more accurately reflect the study cited and inserted information from a more recent study. Tags: use of deprecated (unreliable) source references removed Visual edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

A number of studies have found that [[biology]] can be linked with political orientation.<ref name=Jost2001>{{cite journal|last=Jost|first=John T.|author2=Amodio, David M.|title=Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence|journal=Motivation and Emotion|date=13 November 2011|volume=36|issue=1|pages=55–64|doi=10.1007/s11031-011-9260-7|url=http://www.psych.nyu.edu/jost/Jost-Amodio-2012.pdf}}</ref> This means that biology is a possible factor in political orientation but may also mean that the [[ideology]] a person identifies with changes a person's ability to perform certain tasks. Many of the studies linking biology to politics remain controversial and unreplicated, although the overall body of evidence is growing.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Biology and ideology: The anatomy of politics |last=Buchen |first=Lizzie |date=2012-10-25 |journal=Nature |volume=490 |issue=7421 |pages=466–468 |language=en |doi=10.1038/490466a |pmid = 23099382|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

A number of studies have found that [[biology]] can be linked with political orientation.<ref name=Jost2001>{{cite journal|last=Jost|first=John T.|author2=Amodio, David M.|title=Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence|journal=Motivation and Emotion|date=13 November 2011|volume=36|issue=1|pages=55–64|doi=10.1007/s11031-011-9260-7|url=http://www.psych.nyu.edu/jost/Jost-Amodio-2012.pdf}}</ref> This means that biology is a possible factor in political orientation but may also mean that the [[ideology]] a person identifies with changes a person's ability to perform certain tasks. Many of the studies linking biology to politics remain controversial and unreplicated, although the overall body of evidence is growing.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Biology and ideology: The anatomy of politics |last=Buchen |first=Lizzie |date=2012-10-25 |journal=Nature |volume=490 |issue=7421 |pages=466–468 |language=en |doi=10.1038/490466a |pmid = 23099382|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

||

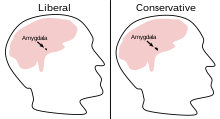

Studies have found that subjects with [[conservative]] political views have larger right [[amygdala]]e<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Schreiber|first=Darren|last2=Fonzo|first2=Greg|last3=Simmons|first3=Alan N.|last4=Dawes|first4=Christopher T.|last5=Flagan|first5=Taru|last6=Fowler|first6=James H.|last7=Paulus|first7=Martin P.|date=2013-02-13|title=Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans|url=https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=8|issue=2|pages=e52970|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|issn=1932-6203|pmc=PMC3572122|pmid=23418419}}</ref> . It plays a role in the expression of fear and in the processing of fear-inducing stimuli. [[Fear conditioning]], which occurs when a neutral stimulus acquires aversive properties, occurs within the right hemisphere. When an individual is presented with a conditioned, aversive stimulus, it is processed within the right amygdala, producing an unpleasant or fearful response. This emotional response conditions the individual to avoid fear-inducing stimuli and more importantly, to assess threats in the environment.<ref>{{Citation|title=Amygdala|date=2020-06-03|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Amygdala&oldid=960506714|work=Wikipedia|language=en|access-date=2020-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

Studies have found that subjects with [[conservative]] political views have larger [[amygdala]]e and are more prone to feeling [[disgust]]. [[Liberalism|Liberals]] have larger volume of grey matter in the [[anterior cingulate cortex]] and are better at detecting errors in recurring patterns. Conservatives have a stronger [[sympathetic nervous system]] response to threatening images and are more likely to interpret ambiguous facial expressions as threatening. In general, conservatives are more likely to report larger social networks, more happiness and better self-esteem than liberals. Liberals are more likely to report greater emotional distress, relationship dissatisfaction and experiential hardship and are more open to experience and tolerate uncertainty and disorder better. |

|||

[[Liberalism|Liberals]] have larger volume of grey matter in left posterior insula <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Schreiber|first=Darren|last2=Fonzo|first2=Greg|last3=Simmons|first3=Alan N.|last4=Dawes|first4=Christopher T.|last5=Flagan|first5=Taru|last6=Fowler|first6=James H.|last7=Paulus|first7=Martin P.|date=2013-02-13|title=Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans|url=https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=8|issue=2|pages=e52970|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|issn=1932-6203|pmc=PMC3572122|pmid=23418419}}</ref> . The insula is active during social decision making. Tiziana Quarto et al. measured [[emotional intelligence]] (EI) (the ability to identify, regulate, and process emotions of themselves and of others) of sixty-three healthy subjects. Using [[Functional magnetic resonance imaging|fMRI]] EI was measured in correlation with left insular activity. The subjects were shown various pictures of [[Facial expression|facial expressions]] and tasked with deciding to approach or avoid the person in the picture. The results of the social decision task yielded that individuals with high EI scores had left insular activation when processing fearful faces.<ref>{{Citation|title=Insular cortex|date=2020-06-27|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Insular_cortex&oldid=964689435|work=Wikipedia|language=en|access-date=2020-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

Genetic factors account for at least some of the variation of political views. From the perspective of [[evolutionary psychology]], conflicts regarding [[redistribution of wealth]] may have been common in the ancestral environment and humans may have developed psychological mechanisms for judging their own chances of succeeding in such conflicts. These mechanisms affect political views. |

|||

Although genetic variation has been shown to contribute to variation in political ideology and strength of partisanship, the portion of the variance in political affiliation explained by activity in the amygdala and insula is significantly larger, suggesting that acting as a partisan in a partisan environment may alter the brain, above and beyond the effect of the heredity.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Schreiber|first=Darren|last2=Fonzo|first2=Greg|last3=Simmons|first3=Alan N.|last4=Dawes|first4=Christopher T.|last5=Flagan|first5=Taru|last6=Fowler|first6=James H.|last7=Paulus|first7=Martin P.|date=2013-02-13|title=Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans|url=https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=8|issue=2|pages=e52970|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0052970|issn=1932-6203|pmc=PMC3572122|pmid=23418419}}</ref> |

|||

==Brain studies== |

==Brain studies== |

||

| Line 13: | Line 15: | ||

A 2011 study by cognitive neuroscientist [[Ryota Kanai]] at [[University College London]] found structural [[brain]] differences between subjects of different political orientation in a [[Accidental sampling|convenience sample]] of students at the same college.<ref name=RK>{{cite journal|title=Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults |author=R. Kanai|journal=Curr Biol|date=2011-04-05|pmid=21474316|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017|volume=21|issue=8|pages=677–80|pmc=3092984|display-authors=etal}}</ref> The researchers performed [[MRI]] scans on the brains of 90 volunteer students who had indicated their political orientation on a five-point scale ranging from "very [[Liberalism|liberal]]" to "very [[conservative]]".<ref name=RK/><ref name=HL>[http://healthland.time.com/2011/04/08/liberal-vs-conservative-does-the-difference-lie-in-the-brain/ Liberal vs. Conservative: Does the Difference Lie in the Brain? – TIME Healthland]</ref> |

A 2011 study by cognitive neuroscientist [[Ryota Kanai]] at [[University College London]] found structural [[brain]] differences between subjects of different political orientation in a [[Accidental sampling|convenience sample]] of students at the same college.<ref name=RK>{{cite journal|title=Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults |author=R. Kanai|journal=Curr Biol|date=2011-04-05|pmid=21474316|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017|volume=21|issue=8|pages=677–80|pmc=3092984|display-authors=etal}}</ref> The researchers performed [[MRI]] scans on the brains of 90 volunteer students who had indicated their political orientation on a five-point scale ranging from "very [[Liberalism|liberal]]" to "very [[conservative]]".<ref name=RK/><ref name=HL>[http://healthland.time.com/2011/04/08/liberal-vs-conservative-does-the-difference-lie-in-the-brain/ Liberal vs. Conservative: Does the Difference Lie in the Brain? – TIME Healthland]</ref> |

||

Students who reported more conservative political views were found to have larger [[amygdala|right amygdala]]e,<ref name=RK/> The amygdala has many functions, including fear processing. Individuals with a large amygdala are more sensitive to fear, which, taken together with our findings, might suggest the testable hypothesis that individuals with larger amygdala are more inclined to integrate conservative views into their belief system. Similarly, it is striking that conservatives are more sensitive to disgust.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kanai|first=Ryota|last2=Feilden|first2=Tom|last3=Firth|first3=Colin|last4=Rees|first4=Geraint|date=2011-04-26|title=Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092984/|journal=Current Biology|volume=21|issue=8|pages=677–680|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017|issn=0960-9822|pmc=3092984|pmid=21474316}}</ref> |

|||

Students who reported more conservative political views were found to have larger [[amygdala]]e,<ref name=RK/> a structure in the [[temporal lobe]]s whose primary function is in the formation, consolidation and processing of [[memory]], as well as positive and negative conditioning (emotional learning).<ref>{{cite book|last=Carlson|first=Neil R.|title=Physiology of Behavior|date=12 January 2012|publisher=Pearson|isbn=978-0205239399|page=364}}</ref> The amygdala is responsible for important roles in social interaction, such as the recognition of emotional cues in facial expressions and the monitoring of personal space,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bzdok D, Langner R, Caspers S, Kurth F, Habel U, Zilles K, Laird A, Eickhoff SB | title = ALE meta-analysis on facial judgments of trustworthiness and attractiveness | journal = Brain Structure & Function | volume = 215 | issue = 3–4 | pages = 209–23 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 20978908 | pmc = 4020344 | doi = 10.1007/s00429-010-0287-4 }}</ref><ref name="Kennedy">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kennedy DP, Gläscher J, Tyszka JM, Adolphs R | title = Personal space regulation by the human amygdala | journal = Nature Neuroscience | volume = 12 | issue = 10 | pages = 1226–7 | date = October 2009 | pmid = 19718035 | pmc = 2753689 | doi = 10.1038/nn.2381 }}</ref> with larger amygdalae correlating with larger and more complex social networks.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bickart KC, Wright CI, Dautoff RJ, Dickerson BC, Barrett LF | title = Amygdala volume and social network size in humans | journal = Nature Neuroscience | volume = 14 | issue = 2 | pages = 163–4 | date = February 2011 | pmid = 21186358 | pmc = 3079404 | doi = 10.1038/nn.2724 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://healthland.time.com/2010/12/28/how-to-win-friends-have-a-big-amygdala/?xid=rss-topstories|title=How to Win Friends: Have a Big Amygdala?|work=Time|first=Maia|last=Szalavitz|date=28 December 2010|access-date=30 December 2010|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110717061203/http://healthland.time.com/2010/12/28/how-to-win-friends-have-a-big-amygdala/?xid=rss-topstories|archive-date=17 July 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref> It is also postulated to play a role in threat detection, including modulation of fear and aggression to perceived threats.<ref>T.L. Brink. (2008) Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. "Unit 4: The Nervous System." pp 61 {{cite web |url=http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/TLBrink_PSYCH04.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=2016-02-07 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303205950/http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/TLBrink_PSYCH04.pdf |archive-date=3 March 2016 |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref name="The human amygdala and the inductio">{{cite journal | vauthors = Feinstein JS, Adolphs R, Damasio A, Tranel D | title = The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear | journal = Current Biology | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | pages = 34–8 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 21167712 | pmc = 3030206 | doi = 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.042 }}</ref><ref name = Staut-1998>{{cite journal | vauthors = Staut CC, Naidich TP | s2cid = 46862405 | title = Urbach-Wiethe disease (Lipoid proteinosis) | journal = Pediatric Neurosurgery | volume = 28 | issue = 4 | pages = 212–4 | date = April 1998 | pmid = 9732251 | doi = 10.1159/000028653 }}</ref> Conservative students were also found to have greater volume of gray matter in the left [[insular cortex|insula]] and the right [[entorhinal cortex]].<ref name=RK/> There is evidence that conservatives are more prone to [[Disgust#Political orientation|disgust]]<ref name=YI>{{cite journal|title= Conservatives are more easily disgusted than liberals. |url=http://yoelinbar.net/papers/disgust_conservatism.pdf | author=Y. Inbar |journal= Cognition and Emotion |date=2008|volume=23|issue=4 |pages=714–725 |doi=10.1080/02699930802110007|display-authors=etal|citeseerx=10.1.1.372.3053 }}</ref> and one role of the insula is in the modulation of social emotions, such as the feeling of disgust to specific sights, smells and norm violations.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Sanfey AG, Rilling JK, Aronson JA, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD |s2cid=7111382 |title=The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game |journal=Science |volume=300 |issue=5626 |pages=1755–8 |date=June 2003 |pmid=12805551 |doi=10.1126/science.1082976 |bibcode=2003Sci...300.1755S }}</ref><ref name=Wicker>{{cite journal|title= Both of us disgusted in My insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust |url=http://www.unipr.it/arpa/mirror/pubs/pdffiles/Gallese/Wickeretal2003.pdf | author=B. Wicker |journal= Neuron |date=2003|volume=40|issue=3 |pages=655–664|display-authors=etal|doi=10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00679-2 |pmid=14642287}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Wright P, He G, Shapira NA, Goodman WK, Liu Y |title=Disgust and the insula: fMRI responses to pictures of mutilation and contamination |journal=NeuroReport |volume=15 |issue=15 |pages=2347–51 |date=October 2004 |pmid=15640753 |doi=10.1097/00001756-200410250-00009}}</ref> |

|||

Students who reported more liberal political views were found to have a larger volume of grey matter in the [[anterior cingulate cortex]],<ref name=RK/>The ACC is involved in certain higher-level functions, such as [[attention]] allocation, [[Pavlovian conditioning|reward anticipation]], [[decision-making]], ethics and [[morality]], impulse control (e.g. performance monitoring and error detection), and [[emotion]].<ref>{{Citation|title=Anterior cingulate cortex|date=2020-07-10|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Anterior_cingulate_cortex&oldid=967048365|work=Wikipedia|language=en|access-date=2020-07-19}}</ref> The findings "of an association between anterior cingulate cortex volume and political attitudes may be linked with tolerance to uncertainty. One of the functions of the anterior cingulate cortex is to monitor uncertainty and conflicts. Thus, it is conceivable that individuals with a larger ACC have a higher capacity to tolerate uncertainty and conflicts, allowing them to accept more liberal views. Such speculations provide a basis for theorizing about the psychological constructs (and their neural substrates) underlying political attitudes."<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kanai|first=Ryota|last2=Feilden|first2=Tom|last3=Firth|first3=Colin|last4=Rees|first4=Geraint|date=2011-04-26|title=Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092984/|journal=Current Biology|volume=21|issue=8|pages=677–680|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017|issn=0960-9822|pmc=3092984|pmid=21474316}}</ref> |

|||

Students who reported more liberal political views were found to have a larger volume of grey matter in the [[anterior cingulate cortex]],<ref name=RK/> a structure of the brain associated with emotional awareness and the emotional processing of pain.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lane RD, Reiman EM, Axelrod B, Yun LS, Holmes A, Schwartz GE | title = Neural correlates of levels of emotional awareness. Evidence of an interaction between emotion and attention in the anterior cingulate cortex | journal = Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience | volume = 10 | issue = 4 | pages = 525–35 | date = July 1998 | pmid = 9712681 | doi = 10.1162/089892998562924 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Price DD | s2cid = 15250446 | title = Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain | journal = Science | volume = 288 | issue = 5472 | pages = 1769–72 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10846154 | doi = 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769 | bibcode = 2000Sci...288.1769P }}</ref> The anterior cingulate cortex becomes active in situations of uncertainty,<ref name=HC>{{cite journal|title= Neural activity in the human brain relating to uncertainty and arousal during anticipation. | author=H. Critchley |journal= Neuron |date=2001|volume=29|issue=2 |pages=537–545 |doi=10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00225-2| pmid=11239442 |display-authors=etal|hdl=21.11116/0000-0001-A313-1 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> and is postulated to play a role in [[error detection]], such as the monitoring and processing of conflicting stimuli or information.<ref name=Bush00>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI | title = Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex | journal = Trends in Cognitive Sciences | volume = 4 | issue = 6 | pages = 215–222 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10827444 | doi = 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2 }}</ref> |

|||

The authors concluded that, "Although our data do not determine whether these regions play a causal role in the formation of political attitudes, they converge with previous work to suggest a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes."<ref name=RK/> In an interview with [[LiveScience]], Ryota Kanai said, "It's very unlikely that actual political orientation is directly encoded in these brain regions", and that, "more work is needed to determine how these brain structures mediate the formation of political attitude."<ref name=Jost2001/><ref name=HL/><ref name=livescience>{{cite web | url=http://www.livescience.com/13608-brain-political-ideology-liberal-conservative.html | title=Politics on the Brain: Scans Show Whether You Lean Left or Right | publisher=[[LiveScience]] | accessdate=September 25, 2012}}</ref><ref name=NYD>{{cite news | url=http://articles.nydailynews.com/2011-04-08/entertainment/29415110_1_brain-structure-political-orientation-liberals-and-conservatives | title=The liberal brain? Scans show liberals and conservatives have different brain structures | newspaper=[[New York Daily News]] | date=April 8, 2011 | accessdate=September 25, 2012 | author=Kattalia, Kathryn}}</ref> Kanai and colleagues added that it is necessary to conduct a longitudinal study to determine whether the changes in brain structure that we observed lead to changes in political behavior or whether political attitudes and behavior instead result in changes of brain structure. |

The authors concluded that, "Although our data do not determine whether these regions play a causal role in the formation of political attitudes, they converge with previous work to suggest a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes."<ref name=RK/> In an interview with [[LiveScience]], Ryota Kanai said, "It's very unlikely that actual political orientation is directly encoded in these brain regions", and that, "more work is needed to determine how these brain structures mediate the formation of political attitude."<ref name=Jost2001/><ref name=HL/><ref name=livescience>{{cite web | url=http://www.livescience.com/13608-brain-political-ideology-liberal-conservative.html | title=Politics on the Brain: Scans Show Whether You Lean Left or Right | publisher=[[LiveScience]] | accessdate=September 25, 2012}}</ref><ref name=NYD>{{cite news | url=http://articles.nydailynews.com/2011-04-08/entertainment/29415110_1_brain-structure-political-orientation-liberals-and-conservatives | title=The liberal brain? Scans show liberals and conservatives have different brain structures | newspaper=[[New York Daily News]] | date=April 8, 2011 | accessdate=September 25, 2012 | author=Kattalia, Kathryn}}</ref> Kanai and colleagues added that it is necessary to conduct a longitudinal study to determine whether the changes in brain structure that we observed lead to changes in political behavior or whether political attitudes and behavior instead result in changes of brain structure. |

||

| Line 29: | Line 31: | ||

A study by scientists at [[New York University]] and the [[University of California, Los Angeles]], found differences in how self-described liberal and conservative research participants responded to changes in patterns.<ref name=NN>David M Amodio, John T Jost, Sarah L Master & Cindy M Yee, [http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v10/n10/abs/nn1979.html Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism], ''[[Nature Neuroscience]]''. Cited by [https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=%22Neurocognitive+correlates+of+liberalism+and+conservatism%E2%80%8E%22&btnG=Search&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=&as_vis=0 69 other studies]</ref> Participants were asked to tap a keyboard when the letter "M" appeared on a computer monitor and to refrain from tapping when they saw a "W". The letter "M" appeared four times more frequently than "W", conditioning participants to press the keyboard when a letter appears. Liberal participants made fewer mistakes than conservatives during testing and their [[electroencephalograph]] readings showed more activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that deals with conflicting information, during the experiment, suggesting that they were better able to detect conflicts in established patterns. The lead author of the study, David Amodio, warned against concluding that a particular political orientation is superior. "The tendency of conservatives to block distracting information could be a good thing depending on the situation," he said.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://psychcentral.com/news/2007/09/10/brains-of-liberals-conservatives-may-work-differently/1691.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161013125516/http://psychcentral.com/news/2007/09/10/brains-of-liberals-conservatives-may-work-differently/1691.html|archive-date=2016-10-13|title=Brains of Liberals, Conservatives May Work Differently|publisher=Psych Central|date=2007-10-20}}</ref><ref name=LATimes2007>{{cite news|url=http://www.latimes.com/news/obituaries/la-sci-politics10sep10,0,2687256.story|title=Study finds left-wing brain, right-wing brain|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=2007-09-10}}</ref> |

A study by scientists at [[New York University]] and the [[University of California, Los Angeles]], found differences in how self-described liberal and conservative research participants responded to changes in patterns.<ref name=NN>David M Amodio, John T Jost, Sarah L Master & Cindy M Yee, [http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v10/n10/abs/nn1979.html Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism], ''[[Nature Neuroscience]]''. Cited by [https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=%22Neurocognitive+correlates+of+liberalism+and+conservatism%E2%80%8E%22&btnG=Search&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=&as_vis=0 69 other studies]</ref> Participants were asked to tap a keyboard when the letter "M" appeared on a computer monitor and to refrain from tapping when they saw a "W". The letter "M" appeared four times more frequently than "W", conditioning participants to press the keyboard when a letter appears. Liberal participants made fewer mistakes than conservatives during testing and their [[electroencephalograph]] readings showed more activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that deals with conflicting information, during the experiment, suggesting that they were better able to detect conflicts in established patterns. The lead author of the study, David Amodio, warned against concluding that a particular political orientation is superior. "The tendency of conservatives to block distracting information could be a good thing depending on the situation," he said.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://psychcentral.com/news/2007/09/10/brains-of-liberals-conservatives-may-work-differently/1691.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161013125516/http://psychcentral.com/news/2007/09/10/brains-of-liberals-conservatives-may-work-differently/1691.html|archive-date=2016-10-13|title=Brains of Liberals, Conservatives May Work Differently|publisher=Psych Central|date=2007-10-20}}</ref><ref name=LATimes2007>{{cite news|url=http://www.latimes.com/news/obituaries/la-sci-politics10sep10,0,2687256.story|title=Study finds left-wing brain, right-wing brain|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=2007-09-10}}</ref> |

||

A study of subjects' reported level of [[disgust]] linked to various scenarios showed that people who scored highly on the "disgust sensitivity" scale held more politically conservative views.<ref name=YI/> However, the findings of a 2019 study suggest that sensitivity to disgust among conservatives varies according to the elicitors used, and that using an elicitor-unspecific scale caused the differences in sensitivity to disappear between those of different political orientations.<ref>Elad-Strenger, Julia, Jutta Proch, and Thomas Kessler. "Is Disgust a "Conservative" Emotion?." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (2019): 0146167219880191.</ref> |

A study of subjects' reported level of [[disgust]] linked to various scenarios showed that people who scored highly on the "disgust sensitivity" scale held more politically conservative views.<ref name="YI">{{cite journal|author=Y. Inbar|display-authors=etal|date=2008|title=Conservatives are more easily disgusted than liberals.|url=http://yoelinbar.net/papers/disgust_conservatism.pdf|journal=Cognition and Emotion|volume=23|issue=4|pages=714–725|citeseerx=10.1.1.372.3053|doi=10.1080/02699930802110007}}</ref> However, the findings of a 2019 study suggest that sensitivity to disgust among conservatives varies according to the elicitors used, and that using an elicitor-unspecific scale caused the differences in sensitivity to disappear between those of different political orientations.<ref>Elad-Strenger, Julia, Jutta Proch, and Thomas Kessler. "Is Disgust a "Conservative" Emotion?." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (2019): 0146167219880191.</ref> |

||

===Physiology=== |

===Physiology=== |

||

Revision as of 02:14, 19 July 2020

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

A number of studies have found that biology can be linked with political orientation.[1] This means that biology is a possible factor in political orientation but may also mean that the ideology a person identifies with changes a person's ability to perform certain tasks. Many of the studies linking biology to politics remain controversial and unreplicated, although the overall body of evidence is growing.[2]

Studies have found that subjects with conservative political views have larger right amygdalae[3] . It plays a role in the expression of fear and in the processing of fear-inducing stimuli. Fear conditioning, which occurs when a neutral stimulus acquires aversive properties, occurs within the right hemisphere. When an individual is presented with a conditioned, aversive stimulus, it is processed within the right amygdala, producing an unpleasant or fearful response. This emotional response conditions the individual to avoid fear-inducing stimuli and more importantly, to assess threats in the environment.[4]

Liberals have larger volume of grey matter in left posterior insula [5] . The insula is active during social decision making. Tiziana Quarto et al. measured emotional intelligence (EI) (the ability to identify, regulate, and process emotions of themselves and of others) of sixty-three healthy subjects. Using fMRI EI was measured in correlation with left insular activity. The subjects were shown various pictures of facial expressions and tasked with deciding to approach or avoid the person in the picture. The results of the social decision task yielded that individuals with high EI scores had left insular activation when processing fearful faces.[6]

Although genetic variation has been shown to contribute to variation in political ideology and strength of partisanship, the portion of the variance in political affiliation explained by activity in the amygdala and insula is significantly larger, suggesting that acting as a partisan in a partisan environment may alter the brain, above and beyond the effect of the heredity.[7]

Brain studies

A 2011 study by cognitive neuroscientist Ryota Kanai at University College London found structural brain differences between subjects of different political orientation in a convenience sample of students at the same college.[8] The researchers performed MRI scans on the brains of 90 volunteer students who had indicated their political orientation on a five-point scale ranging from "very liberal" to "very conservative".[8][9]

Students who reported more conservative political views were found to have larger right amygdalae,[8] The amygdala has many functions, including fear processing. Individuals with a large amygdala are more sensitive to fear, which, taken together with our findings, might suggest the testable hypothesis that individuals with larger amygdala are more inclined to integrate conservative views into their belief system. Similarly, it is striking that conservatives are more sensitive to disgust.[10]

Students who reported more liberal political views were found to have a larger volume of grey matter in the anterior cingulate cortex,[8]The ACC is involved in certain higher-level functions, such as attention allocation, reward anticipation, decision-making, ethics and morality, impulse control (e.g. performance monitoring and error detection), and emotion.[11] The findings "of an association between anterior cingulate cortex volume and political attitudes may be linked with tolerance to uncertainty. One of the functions of the anterior cingulate cortex is to monitor uncertainty and conflicts. Thus, it is conceivable that individuals with a larger ACC have a higher capacity to tolerate uncertainty and conflicts, allowing them to accept more liberal views. Such speculations provide a basis for theorizing about the psychological constructs (and their neural substrates) underlying political attitudes."[12]

The authors concluded that, "Although our data do not determine whether these regions play a causal role in the formation of political attitudes, they converge with previous work to suggest a possible link between brain structure and psychological mechanisms that mediate political attitudes."[8] In an interview with LiveScience, Ryota Kanai said, "It's very unlikely that actual political orientation is directly encoded in these brain regions", and that, "more work is needed to determine how these brain structures mediate the formation of political attitude."[1][9][13][14] Kanai and colleagues added that it is necessary to conduct a longitudinal study to determine whether the changes in brain structure that we observed lead to changes in political behavior or whether political attitudes and behavior instead result in changes of brain structure.

Functional differences

Psychometry

Various studies suggest measurable differences in the psychological traits of liberals and conservatives. Conservatives are more likely to report larger social networks, greater happiness and self-esteem than liberals, are more reactive to perceived threats and more likely to interpret ambiguous facial expressions as threatening.[15][16][17] Liberals are more likely to report greater emotional distress, relationship dissatisfaction and experiential hardship than conservatives, and show more openness to experience as well as greater tolerance for uncertainty and disorder.[15][17]

Behavioral studies

A study by scientists at New York University and the University of California, Los Angeles, found differences in how self-described liberal and conservative research participants responded to changes in patterns.[18] Participants were asked to tap a keyboard when the letter "M" appeared on a computer monitor and to refrain from tapping when they saw a "W". The letter "M" appeared four times more frequently than "W", conditioning participants to press the keyboard when a letter appears. Liberal participants made fewer mistakes than conservatives during testing and their electroencephalograph readings showed more activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that deals with conflicting information, during the experiment, suggesting that they were better able to detect conflicts in established patterns. The lead author of the study, David Amodio, warned against concluding that a particular political orientation is superior. "The tendency of conservatives to block distracting information could be a good thing depending on the situation," he said.[19][20]

A study of subjects' reported level of disgust linked to various scenarios showed that people who scored highly on the "disgust sensitivity" scale held more politically conservative views.[21] However, the findings of a 2019 study suggest that sensitivity to disgust among conservatives varies according to the elicitors used, and that using an elicitor-unspecific scale caused the differences in sensitivity to disappear between those of different political orientations.[22]

Physiology

Persons with right-wing views had greater skin conductance response, indicating greater sympathetic nervous system response, to threatening images than those with left-wing views in one study. There was no difference for positive or neutral images. Holding right-wing views was also associated with a stronger startle reflex as measured by strength of eyeblink in response to unexpected noise.[1]

In an fMRI study published in Social Neuroscience, three different patterns of brain activation were found to correlate with individualism, conservatism, and radicalism.[23] In general, fMRI responses in several portions of the brain have been linked to viewing of the faces of well-known politicians.[24] Others believe that determining political affiliation from fMRI data is overreaching.[25]

Genetic studies

Heritability

Heritability compares differences in genetic factors in individuals to the total variance of observable characteristics ("phenotypes") in a population, to determine the heritability coefficient. Factors including genetics, environment and random chance can all contribute to the variation in individuals' phenotypes.[26]

The use of twin studies assumes the elimination of non-genetic differences by finding the statistical differences between monozygotic (identical) twins, which have almost the same genes, and dizygotic (fraternal) twins.[27] The similarity of the environment in which twins are reared has been questioned.[28][29]

A 2005 twin study examined the attitudes regarding 28 different political issues such as capitalism, unions, X-rated movies, abortion, school prayer, divorce, property taxes, and the draft. Twins were asked if they agreed or disagreed or were uncertain about each issue. Genetic factors accounted for 53% of the variance of an overall score. However, self-identification as Republican and Democrat had a much lower heritability of 14%.[30][31]

Jost et al. wrote in a 2011 review that "Many studies involving quite diverse samples and methods suggest that political and religious views reflect a reasonably strong genetic basis, but this does not mean that ideological proclivities are unaffected by personal experiences or environmental factors."[1]

Gene association studies

"A Genome-Wide Analysis of Liberal and Conservative Political Attitudes" by Peter K. Hatemi et al. traces DNA research involving 13,000 subjects. The study identifies several genes potentially connected with political ideology.[32]

Evolutionary psychology

From an evolutionary psychology perspective, conflicts regarding redistribution of wealth may have been a recurrent issue in the ancestral environment. Humans may therefore have developed psychological mechanisms for judging their chance of succeeding in such conflicts which will affect their political views. For males, physical strength may have been an important factor in deciding the outcome of such conflicts. Therefore, a prediction is that males having high physical strength and low socioeconomic stratum (SES) will support redistribution while males having both high SES and high physical strength will oppose redistribution. Cross-cultural research found this to be the case; for females, their physical strength had no influence on their political views which was as expected since females rarely have physical strength above that of the average male.[33] A study on political attitudes among Hollywood actors found that, while the actors were generally more left-leaning, male actors with great physical strength were more likely to support the Republican stance on foreign issues and foreign military interventions.[34]

An alternative evolutionary explanation for political diversity is that it is a polymorphism, like those of gender and blood type, resulting from frequency-dependent selection. Tim Dean has suggested that we live in such a moral ecosystem whereby the viability of any existing moral approach would be diminished by the destruction of all alternative approaches[35] (e.g. political balance promotes survival of the human species).

See also

- Amygdala hijack

- Biology and political science

- Biological determinism

- Brain types

- Genopolitics

- Neuropolitics

- Replication crisis

References

- ^ a b c d Jost, John T.; Amodio, David M. (13 November 2011). "Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence" (PDF). Motivation and Emotion. 36 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9260-7.

- ^ Buchen, Lizzie (2012-10-25). "Biology and ideology: The anatomy of politics". Nature. 490 (7421): 466–468. doi:10.1038/490466a. PMID 23099382.

- ^ Schreiber, Darren; Fonzo, Greg; Simmons, Alan N.; Dawes, Christopher T.; Flagan, Taru; Fowler, James H.; Paulus, Martin P. (2013-02-13). "Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e52970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052970. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3572122. PMID 23418419.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Amygdala", Wikipedia, 2020-06-03, retrieved 2020-07-19

- ^ Schreiber, Darren; Fonzo, Greg; Simmons, Alan N.; Dawes, Christopher T.; Flagan, Taru; Fowler, James H.; Paulus, Martin P. (2013-02-13). "Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e52970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052970. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3572122. PMID 23418419.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Insular cortex", Wikipedia, 2020-06-27, retrieved 2020-07-19

- ^ Schreiber, Darren; Fonzo, Greg; Simmons, Alan N.; Dawes, Christopher T.; Flagan, Taru; Fowler, James H.; Paulus, Martin P. (2013-02-13). "Red Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e52970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052970. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3572122. PMID 23418419.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e R. Kanai; et al. (2011-04-05). "Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults". Curr Biol. 21 (8): 677–80. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017. PMC 3092984. PMID 21474316.

- ^ a b Liberal vs. Conservative: Does the Difference Lie in the Brain? – TIME Healthland

- ^ Kanai, Ryota; Feilden, Tom; Firth, Colin; Rees, Geraint (2011-04-26). "Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults". Current Biology. 21 (8): 677–680. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 3092984. PMID 21474316.

- ^ "Anterior cingulate cortex", Wikipedia, 2020-07-10, retrieved 2020-07-19

- ^ Kanai, Ryota; Feilden, Tom; Firth, Colin; Rees, Geraint (2011-04-26). "Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults". Current Biology. 21 (8): 677–680. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 3092984. PMID 21474316.

- ^ "Politics on the Brain: Scans Show Whether You Lean Left or Right". LiveScience. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Kattalia, Kathryn (April 8, 2011). "The liberal brain? Scans show liberals and conservatives have different brain structures". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ a b J. Vigil; et al. (2010). "Political leanings vary with facial expression processing and psychosocial functioning". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 13 (5): 547–558. doi:10.1177/1368430209356930.

- ^ J. Jost; et al. (2006). "The end of the end of ideology" (PDF). American Psychologist. 61 (7): 651–670. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.61.7.651. PMID 17032067.

- ^ a b J. Jost; et al. (2003). "Political conservatism as motivated social cognition" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 129 (3): 339–375. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339. PMID 12784934.

- ^ David M Amodio, John T Jost, Sarah L Master & Cindy M Yee, Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism, Nature Neuroscience. Cited by 69 other studies

- ^ "Brains of Liberals, Conservatives May Work Differently". Psych Central. 2007-10-20. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13.

- ^ "Study finds left-wing brain, right-wing brain". Los Angeles Times. 2007-09-10.

- ^ Y. Inbar; et al. (2008). "Conservatives are more easily disgusted than liberals" (PDF). Cognition and Emotion. 23 (4): 714–725. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.372.3053. doi:10.1080/02699930802110007.

- ^ Elad-Strenger, Julia, Jutta Proch, and Thomas Kessler. "Is Disgust a "Conservative" Emotion?." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (2019): 0146167219880191.

- ^ Zamboni G, Gozzi M, Krueger F, Duhamel JR, Sirigu A, Grafman J (2009). "Individualism, conservatism, and radicalism as criteria for processing political beliefs: a parametric fMRI study". Social Neuroscience. 4 (5): 367–83. doi:10.1080/17470910902860308. PMID 19562629. Zamboni G, Gozzi M, Krueger F, Duhamel JR, Sirigu A, Jordan Grafman. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

- ^ Kristine Knudson; et al. (March 2006). "Politics on the Brain: An fMRI Investigation". Soc Neurosci. 1 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1080/17470910600670603. PMC 1828689. PMID 17372621.

- ^ Aue T, Lavelle LA, Cacioppo JT (July 2009). "Great expectations: what can fMRI research tell us about psychological phenomena?" (PDF). International Journal of Psychophysiology. 73 (1): 10–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.017. PMID 19232374.

- ^ Raj, A; van Oudenaarden, A (2008). "Nature, nurture, or chance: stochastic gene expression and its consequences". Cell. 135 (2): 216–26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050. PMC 3118044. PMID 18957198.

- ^ A twin-pronged attack on complex traits, N. Martin, D. Boomsma and G. Machin. (1997). Nature Genetics, 17, 387-92. 10.1038/ng1297-387

- ^ Jon Beckwith and Corey A. Morris. Twin Studies of Political Behavior: Untenable Assumptions? Perspectives on Politics (2008), 6 : pp 785-791

- ^ Handbook of Social Psychology, Volume 1. Susan T. Fiske, Daniel T. Gilbert, Gardner Lindzey. p. 372.

- ^ Carey, Benedict (June 21, 2005). "Some Politics May Be Etched in the Genes". The New York Times. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Alford, J. R.; Funk, C. L.; Hibbing, J. R. (2005). "Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted?". American Political Science Review. 99 (2): 153–167. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.622.476. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051579.

- ^ Hatemi, P. K.; Gillespie, N. A.; Eaves, L. J.; Maher, B. S.; Webb, B. T.; Heath, A. C.; Medland, S. E.; Smyth, D. C.; Beeby, H. N.; Gordon, S. D.; Montgomery, G. W.; Zhu, G.; Byrne, E. M.; Martin, N. G. (2011). "A Genome-Wide Analysis of Liberal and Conservative Political Attitudes". The Journal of Politics. 73: 271–285. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.662.2987. doi:10.1017/S0022381610001015.

- ^ Michael Bang Petersen. The evolutionary psychology of Mass Politics. In Roberts, S. C. (2011). Roberts, S. Craig (ed.). Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586073.001.0001. ISBN 9780199586073.

- ^ "Strong men more likely to vote Conservative". The Telegraph. April 11, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Dean, T. (2012). "Evolution and Moral Diversity". The Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication. 7. doi:10.4148/biyclc.v7i0.1775.

Further reading

- Some Politics May Be Etched in the Genes - The New York Times,

- Political Views Reflected in Brain Structure - ABC

- Liberals and conservatives don’t just vote differently. They think differently. - The Washington Post

- Body politic. The genetics of politics. Slowly, and in some quarters grudgingly, the influence of genes in shaping political outlook and behaviour is being recognised - The Economist, Oct 6th 2012