1935 New Zealand general election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 80 seats in the New Zealand Parliament 41 seats were needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

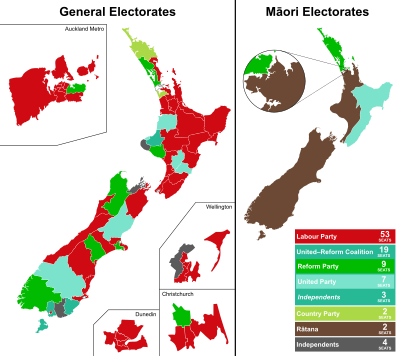

Results of the election. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1935 New Zealand general election was a nationwide vote to determine the shape of the New Zealand Parliament's 25th term. It resulted in the Labour Party's first electoral victory, with Michael Joseph Savage becoming the first Labour Prime Minister after defeating the governing coalition, consisting of the United Party and the Reform Party, in a landslide.

The governing coalition lost 31 seats, which was attributed by many to their handling of the Great Depression: the year after the election, the United and Reform parties merged to form the modern National Party.

The election was originally scheduled to be held in 1934, in keeping with the country's three-year election cycle, but the governing coalition postponed the election by one year hoping that the economic conditions would improve by 1935.[1]

Background

Since 1931, New Zealand had been governed by a coalition of the United Party and the Reform Party, the United–Reform Coalition. United and Reform had traditionally been enemies – United was a revival of the old Liberal Party, a progressive party with a strong urban base, while Reform was a conservative party with a strong rural base. When the 1928 elections left United and Reform with an equal number of seats, United managed to obtain support from the growing Labour Party, but in 1931, the worsening depression prompted a dispute over economic policy, and Labour withdrew its backing. Reform then agreed to go into coalition with United, fearing that an election would lead to significant gains for the "socialistic" Labour. The coalition held on to power in the 1931 elections, but the ongoing economic troubles made the government deeply unpopular, and by the time of the 1935 elections, Labour's support was soaring.

On Sunday 24 November, shortly before the election, an address by Colin Scrimgeour ("Uncle Scrim") on the Friendly Road radio station, which was expected to urge listeners to vote Labour, was jammed by the Post Office.

Campaign

The Dominion, a Wellington newspaper, printed anti-Labour advertisements and editorials.[2]

The election

The number of electorates being contested was 80, a number which had been fixed since the 1902 Electoral Redistribution.[3][4]

Four of those were Māori electorates, and those elections were held on 26 November.[5] 19 candidates contested the four available positions, and in three out of four cases, the incumbents were returned.[6][7]

The election in the European electorates was held on the following day, a Wednesday.[5] A total of 246 candidates contested the 76 European electorates, between two and six per electorate (Wellington East had six candidates, and there was a contest in all electorates), i.e. an average of 3.2 candidates per electorate.[8] 919,798 people were registered to vote in European electorates (enrolment data for Māori electorates are only available since the 1954 election), and there was a turnout of 90.75%.[9] This turnout was considerably higher than the turnout in the previous election (84.26%) and the highest turnout so far, but still about average for the next decades.[9]

Elsie Andrews (1888–1948) was one of only three women who stood for election in this year.[10]

Results

Summary

The 1935 election saw a massive win for the opposition Labour Party, which won fifty-three seats, and formed the First Labour Government. The governing coalition won only nineteen, and three ministers were defeated (in Hamilton, Tauranga and Waitaki). This difference was not so great in the popular vote, however, with Labour winning 45.7% to the coalition's 33.5%. Labour was more fortunate than its British namesake in not attaining office before the depression (thanks to Seddon's lengthy reign) "and so could hold the conservative coalition responsible if natural laws of economics behaved unnaturally".[11]

Apart from Labour and the coalition, the only two groups to win places in Parliament were the Country Party and the Ratana movement, both of which won two seats.

Four independents were elected, Harry Atmore, David McDougall, Charles Wilkinson and Robert Wright. The independents were tactically supported by one of the major parties who did not stand a candidate against them, and they generally voted with that party; Wilkinson and Wright supported the coalition while Atmore and McDougall supported Labour. Labour also did not stand candidates against the two Country Party members.[12]

Many commentators blamed the coalition's failure to win seats on vote splitting by the Democrat Party, an "anti-socialist" group founded by a former organiser for the governing coalition, Albert Davy, and headed by Thomas Hislop, the Mayor of Wellington. Perhaps as many as eight seats were an unexpected bonus to Labour because of the three-way split.[13] The Democrats won 7.8% of the vote, but no seats.

Two future National MPs stood unsuccessfully: Frederick Doidge stood as an Independent for Rotorua and came second, and Matthew Oram stood for the Democrats in Manawatu and came fourth.[14]

An analysis of men and women on the rolls against the votes recorded showed that in 1935 90.75% of those on the European rolls voted; men 92.02% and women 89.46%. In the 1938 election the figures were 92.85% with men 93.43% and women 92.27%. As the Māori electorates did not have electoral rolls they could not be included.[15][16]

Party totals

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election results | |||||||

| Party | Candidates | Votes | Percentage | Seats | change | ||

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Labour | 70 | 389,911 | 45.73 | 53 | +29 | |

| Template:Meta color | width=5 rowspan=2 bgcolor=Template:United–Reform Coalition/meta/color| | Reform | 74 | 285,422 | 33.48 | 9 | −31 |

| bgcolor=Template:United Party (New Zealand)/meta/color| | United | 7 | |||||

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Democrats | 53 | 66,695 | 7.82 | 0 | - | |

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Country Party | 6 | 11,809 | 1.67 | 2 | +1 | |

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Ratana | 4 | 6,249 | 0.73 | 2 | +2 | |

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Communist | 4 | 600 | 0.07 | 0 | ±0 | |

| colspan=2 Template:Meta color | Independents | 60 | 87,748 | 10.29 | 7 | –1 | |

| Total: | 267 | 852,637 | 100 | 80 | |||

Votes summary

Electorate results

The following table shows the detailed results: Template:1935 New Zealand general election

Post-election events

A number of local by-elections were required due to the resignations of incumbent local body politicians following the general election:

- In February 1936 Dan Sullivan resigned as Mayor of Christchurch owing to a heavy workload after becoming a cabinet minister following Labour's victory. This sparked a two by-elections, one for the mayoralty and another for three vacancies on the city council. Sullivan was replaced by John Beanland.[17] Among the successful city council candidates was Robert Macfarlane who had contested Christchurch North in 1935.[18]

- Likewise Peter Fraser resigned his seat on the Wellington City Council in order to focus on his new ministerial duties. A by-election was avoided however when Andrew Parlane, the highest polling unsuccessful candidate from the previous election, was the only nominated candidate.[19]

- Later in the parliamentary term Fred Jones resigned his membership of the Dunedin City Council due to his ministerial obligations. An appointment was made instead of holding a by-election with Ralph Harrison succeeding Jones.[20]

Notes

- ^ Simpson, Tony. "The Sugarbag Years". 1990 Penguin Books p. 212.

- ^ Fensome, Alex (12 December 2014). "Savage voters ignored slur of reds and poisoned chocs". The Dominion Post. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "General elections 1853–2005 – dates & turnout". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ^ McRobie 1989, p. 67.

- ^ a b Wilson 1985, p. 138.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

7 December EPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Maori Seatswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "The General Election". The Evening Post. Vol. CXX, no. 128. 26 November 1935. p. 20. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ a b Wilson 1985, p. 286.

- ^ "Untitled". The New Zealand Herald. Vol. LXXII, no. 22277. 27 November 1935. p. 5. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Lipson 2011, p. 210.

- ^ Milne, Robert Stephen (1966). Political Parties in New Zealand. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. p. 76.

- ^ Bassett, Michael (2000). Tomorrow Comes the Song: A life of Peter Fraser. Auckland: Penguin. p. 136. ISBN 0-14-029793-6.

- ^ "Government overwhelmed, People's emphatic mandate, Democrat Party rejected". Papers Past. 28 November 1935.

- ^ New Zealand Official Year-book, 1942 p778

- ^ "The New Zealand Official Year-Book, 1942". Government Printer. 28 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Mayor's Reduced Majority". The Press. Vol. LXXII, no. 21732. 14 March 1936. p. 18. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Cost of city by-election". The Press. Vol. LXXII, no. 21734. 17 March 1936. p. 16. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "No by-election". The Evening Post. Vol. CXXI, no. 109. 9 May 1936. p. 10. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ "A New Councillor − Mr. R. Harrison Appointed". Otago Daily Times. No. 23368. 7 December 1937. p. 8. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

References

- Gustafson, Barry (1986). The First 50 Years : A History of the New Zealand National Party. Auckland: Reed Methuen. ISBN 0-474-00177-6.

- McRobie, Alan (1989). Electoral Atlas of New Zealand. Wellington: GP Books. ISBN 0-477-01384-8.

- Lipson, Leslie (2011) [1948]. The Politics of Equality: New Zealand's Adventures in Democracy. Wellington: Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0-86473-646-8.

- Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [First published in 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. OCLC 154283103.