40-foot telescope

| |

| Alternative names | Great Forty-Foot telescope |

|---|---|

| Location(s) | Slough, Borough of Slough, Berkshire, South East England, England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′30″N 0°35′43″W / 51.5082°N 0.5954°W |

| Built | 1785–1789 |

| First light | 19 February 1787 |

| Decommissioned | 1840 |

| Telescope style | altazimuth mount reflecting telescope |

| Diameter | 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) |

| Focal length | 12 m (39 ft 4 in) |

| | |

William Herschel's 40-foot telescope, also known as the Great Forty-Foot telescope, was a reflecting telescope constructed between 1785 and 1789 at Observatory House in Slough, England. It used a 120-centimetre (47 in) diameter primary mirror with a 12-metre-long (1,200 cm) focal length (hence its name "Forty-Foot"). It was the largest telescope in the world for 50 years. It may have been used to discover Enceladus and Mimas, the 6th and 7th moons of Saturn. It was dismantled in 1840; today the original mirror and a 10-foot (3.0 m) section of the tube remain.

Construction

The telescope was constructed by Sir William Herschel, with the assistance of Caroline Herschel, between 1785 and 1789 in Slough, with components made in Clay Hall near Windsor. The 40 ft (12 m) tube was made of iron.[1] The telescope was mounted on a fully rotatable alt-azimuth mount. It was paid for by King George III, who granted £4,000 for it to be made.[1] During construction, whilst the telescope tube lay on the ground, the King as well as the Archbishop of Canterbury visited the telescope. Just prior to them entering the open mouth of the tube, the King commented "Come, my Lord Bishop, I will show you the way to Heaven!"[2]

Two 48-inch (120 cm) concave metal mirrors were made for the telescope, each with a focal ratio of f/10.[2] The first was cast in a London foundry on 31 October 1785,[3] and was made of speculum (an alloy of mostly copper and tin) with arsenic to improve the finish.[4][5] It weighed 1023 lb after being cast, but it was found to be 0.9 inches thinner at the centre than at the edge (where it was around 2 inches thick). Over a year was spent grinding and polishing the mirror; however, Herschel found it to be "much too thin to keep its figure when put into the telescope"[3] (despite weighing half a ton). A second mirror with twice the thickness of the original was cast a few years later, and this was used rather than the original. However, this required more frequent polishing due to the fast tarnishing nature of the metal, and the original mirror was used when the second was being polished. The mirrors remained the largest in the world until 1845.[4][5]

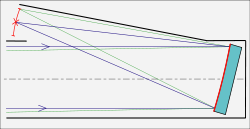

Herschel eliminated the small diagonal mirror of a standard newtonian reflector from his design and instead tilted his primary mirror so he could view the formed image when he stood in an observing cage directly in front of the telescope. This saved on the severe light loss the image would suffer if he had used a speculum metal diagonal mirror. This design has come to be called a Herschelian telescope.[6]

Use

The telescope was located on the grounds of Observatory House, Herschel's house in Slough, between 1789 and 1840.[1] The first observation with the telescope was on 19 February 1787, when Herschel pointed the then-incomplete telescope towards the Orion nebula, which he observed by crawling into the telescope and using a hand-held eyepiece:[3][5] "The apparatus for the 40-foot telescope was by this time so far completed that I could put the mirror into the tube and direct it to a celestial object; but having no eye-glass fixed, not being acquainted with the focal length which was to be tried, I went into the tube, and laying down near the mouth of it I held the eye-glass in my hand, and soon found the place of the focus. The object I viewed was the nebula in the belt of Orion, and I found the figure of the mirror, though far from perfect, better than I had expected. It showed four small stars in the nebula and many more. The nebula was extremely bright."

The one achievement of the telescope was to discover Enceladus and Mimas, the 6th and 7th moons of Saturn, although this is not certain, as Herschel used other telescopes at the same time.[1] Herschel described the view of Sirius through the telescope:[2] "... the appearance of Sirius announced itself, ... and came on by degrees, increasing in brightness, till this brilliant star at last entered the field of view of the telescope, with all the splendour of the rising sun, and forced me to take the eye from that beautiful sight."

As part of the funding deal with the telescope, Caroline Herschel was granted a pension of £50 per year to be William's assistant. As a result, she was the first woman in England to be paid to carry out astronomy.[1]

The telescope was a local tourist attraction,[7] visited by rich and famous people on their way to the nearby Windsor Castle to visit the King,[4] and was featured on Ordnance Survey maps.[7] It was the largest telescope in the world for 50 years.[1] It was called the "40-foot telescope" as at the time telescopes were referred to by the length of their tube rather than the diameter of the mirror.[2]

Due to problems with the mirrors and because the telescope was unwieldy, the telescope did not prove to be a substantial improvement over smaller telescopes.[5] The weather was rarely suitable for the telescope, and most objects observed by Herschel were also visible in his smaller telescopes.[2] The final observation made by the telescope was in 1815.[1]

The telescope was featured in Herschel's coat of arms: "Argent on a mount vert a representation of the forty-feet reflecting telescope with its apparatus proper; a chief azure thereon the astronomical symbol of Uranus or Georgium Sidus irradiated Or."[8]

Decommissioning and preservation

The telescope's frame was dismantled at the end of 1839 by William Herschel's son, John Herschel,[1][3] on his return from carrying out observations in South Africa. It was dismantled as it was feared that the frame might collapse due to rot, and John feared for the safety of his young children. A small ceremony was conducted to commemorate its dismantling.[9]

The tube was left lying horizontally in the garden, supported by stone blocks at either end, where it was crushed in 1867 by a falling tree.[3] The remaining piece is a 10-foot (3.0 m) length of the mirror end, which is 3,048 by 1,465 mm (120" x 57.7"). This was still located in the garden of Observatory House in 1955,[10] but was subsequently moved and is now located in the Herschel Collection of the National Maritime Museum, in the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London.[1]

The first mirror was last polished in 1797, and was subsequently stored away and lost. When John Herschel moved from Observatory House to Hawkhurst in 1840, a number of items (including the 40-foot telescope) were left behind. In an inventory written at the time, he recorded "In the Observatory, beneath stair, one 40-foot mirror, with case and cover." A workman later reported that only a light metal cover of a 4-foot mirror was present, rather than the mirror itself. The mirror was rediscovered on 2 February 1927: "All that could be seen on a casual inspection was a somewhat rusty iron ring, about 4 feet in diameter and 5 inches thick ... covered in front with a close-fitting lid of thin metal. The iron ring, which was not unlike the tyre of a cart-wheel, was obviously the cell of a large mirror and was quite separate from the tin cover. On removing the latter, which was provided with six handles, the mirror itself was at once seen, occupying the front portion of the cell, close under the cover."[3]

On 4 March 1927 the mirror was moved to the Cottage library, and was once more polished some 130 years after the mirror was last properly polished.[3] The original mirror now resides in the Science Museum, London.[11] The second mirror was left in place in the telescope when it was dismantled, but was removed when the tube was crushed. In 1871 it was moved into the hall of Observatory House.[3]

A scale model of the telescope, as well as an early photo of it that is framed in wood from the telescope, is on display at the Herschel Museum of Astronomy.[12]

The 40-foot (12 m) telescope was surpassed in 1845 as the largest ever built by Lord Rosse's great 72-inch (1.8 m) reflecting telescope.[10] The image of the 40-foot telescope remains as one of the great icons of astronomy.[2]

See also

- List of largest optical telescopes historically

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 18th century

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "40-foot Herschelian (reflector) telescope tube remains (AST0947)". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Mullaney, James (2007). "Chapter 2, Herschel's Telescopes". The Herschel Objects and How to Observe Them. pp. 10–15. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68125-2_2. ISBN 978-0-387-68125-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Steavenson, W. H. (April 1927). "Herschel's first 40-foot speculum". The Observatory. 50: 114–118. Bibcode:1927Obs....50..114S.

- ^ a b c "Original mirror for William Herschel's 40 foot telescope, 1785". Science & Society Picture Library. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Original mirror for William Herschel's 40-foot telescope, 1785". The Science Museum. 2004. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Telescope". catalogue.museogalileo.it — Institute and Museum of the History of Science. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Herschel's Grand Forty feet Reflecting Telescopes (ZBA4492)". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Franklyn, Julian. Shield and Crest. London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1961. P. 250.

- ^ "'Slough. The 40ft reflector with all the woodwork down' (PAF7451)". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b Berendzen, Richard; Hart, Richard; Seeley, Daniel (1976). Man Discovers the Galaxies. Science History Publications. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-88202-023-4.

- ^ "Original mirror for William Herschel's forty-foot telescope, 1785". Science Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ "Telescopes". Herschel Museum. Retrieved 15 December 2014.