Acid strength

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbolised by the chemical formula , to dissociate into a proton, , and an anion, . The dissociation of a strong acid in solution is effectively complete, except in its most concentrated solutions.

Examples of strong acids are hydrochloric acid , perchloric acid , nitric acid and sulfuric acid .

A weak acid is only partially dissociated, with both the undissociated acid and its dissociation products being present, in solution, in equilibrium with each other.

Acetic acid () is an example of a weak acid. The strength of a weak acid is quantified by its acid dissociation constant, value.

The strength of a weak organic acid may depend on substituent effects. The strength of an inorganic acid is dependent on the oxidation state for the atom to which the proton may be attached. Acid strength is solvent-dependent. For example, hydrogen chloride is a strong acid in aqueous solution, but is a weak acid when dissolved in glacial acetic acid.

Measures of acid strength

The usual measure of the strength of an acid is its acid dissociation constant (), which can be determined experimentally by titration methods. Stronger acids have a larger and a smaller logarithmic constant () than weaker acids. The stronger an acid is, the more easily it loses a proton, . Two key factors that contribute to the ease of deprotonation are the polarity of the bond and the size of atom A, which determine the strength of the bond. Acid strengths also depend on the stability of the conjugate base.

While the value measures the tendency of an acidic solute to transfer a proton to a standard solvent (most commonly water or DMSO), the tendency of an acidic solvent to transfer a proton to a reference solute (most commonly a weak aniline base) is measured by its Hammett acidity function, the value. Although these two concepts of acid strength often amount to the same general tendency of a substance to donate a proton, the and values are measures of distinct properties and may occasionally diverge. For instance, hydrogen fluoride, whether dissolved in water ( = 3.2) or DMSO ( = 15), has values indicating that it undergoes incomplete dissociation in these solvents, making it a weak acid. However, as the rigorously dried, neat acidic medium, hydrogen fluoride has an value of –15,[1] making it a more strongly protonating medium than 100% sulfuric acid and thus, by definition, a superacid.[2] (To prevent ambiguity, in the rest of this article, "strong acid" will, unless otherwise stated, refer to an acid that is strong as measured by its value ( < –1.74). This usage is consistent with the common parlance of most practicing chemists.)

When the acidic medium in question is a dilute aqueous solution, the is approximately equal to the pH value, which is a negative logarithm of the concentration of aqueous in solution. The pH of a simple solution of an acid in water is determined by both and the acid concentration. For weak acid solutions, it depends on the degree of dissociation, which may be determined by an equilibrium calculation. For concentrated solutions of acids, especially strong acids for which pH < 0, the value is a better measure of acidity than the pH.

Strong acids

A strong acid is an acid that dissociates according to the reaction

where S represents a solvent molecule, such as a molecule of water or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), to such an extent that the concentration of the undissociated species is too low to be measured. For practical purposes a strong acid can be said to be completely dissociated. An example of a strong acid is hydrochloric acid

- (in aqueous solution)

Any acid with a value which is less than about -2 is classed as a strong acid. This results from the very high buffer capacity of solutions with a pH value of 1 or less and is known as the leveling effect.[3]

The following are strong acids in aqueous and dimethyl sulfoxide solution. The values of , cannot be measured experimentally. The values in the following table are average values from as many as 8 different theoretical calculations.

Estimated pKa values[4] Acid Formula in water in DMSO Hydrochloric acid HCl −5.9 ± 0.4 −2.0 ± 0.6 Hydrobromic acid HBr −8.8 ± 0.8 −6.8 ± 0.8 Hydroiodic acid HI −9.5 ± 1 −10.9 ± 1 Triflic acid H[CF3SO3] −14 ± 2 −14 ± 2 Perchloric acid H[ClO4] −15 ± 2 −15 ± 2

Also, in water

- Nitric acid = −1.6 [5]

- Sulfuric acid (first dissociation only, ≈ −3)[6]: (p. 171)

The following can be used as protonators in organic chemistry

Sulfonic acids, such as p-toluenesulfonic acid (tosylic acid) are a class of strong organic oxyacids.[7] Some sulfonic acids can be isolated as solids. Polystyrene functionalized into polystyrene sulfonate is an example of a substance that is a solid strong acid.

Weak acids

A weak acid is a substance that partially dissociates when it is dissolved in a solvent. In solution there is an equilibrium between the acid, , and the products of dissociation.

The solvent (e.g. water) is omitted from this expression when its concentration is effectively unchanged by the process of acid dissociation. The strength of a weak acid can be quantified in terms of a dissociation constant, , defined as follows, where signifies the concentration of a chemical moiety, X.

When a numerical value of is known it can be used to determine the extent of dissociation in a solution with a given concentration of the acid, , by applying the law of conservation of mass.

where is the value of the analytical concentration of the acid. When all the quantities in this equation are treated as numbers, ionic charges are not shown and this becomes a quadratic equation in the value of the hydrogen ion concentration value, .

This equation shows that the pH of a solution of a weak acid depends on both its value and its concentration. Typical examples of weak acids include acetic acid and phosphorous acid. An acid such as oxalic acid () is said to be dibasic because it can lose two protons and react with two molecules of a simple base. Phosphoric acid () is tribasic.

For a more rigorous treatment of acid strength see acid dissociation constant. This includes acids such as the dibasic acid succinic acid, for which the simple method of calculating the pH of a solution, shown above, cannot be used.

Experimental determination

The experimental determination of a value is commonly performed by means of a titration.[8] A typical procedure would be as follows. A quantity of strong acid is added to a solution containing the acid or a salt of the acid, to the point where the compound is fully protonated. The solution is then titrated with a strong base

until only the deprotonated species, , remains in solution. At each point in the titration pH is measured using a glass electrode and a pH meter. The equilibrium constant is found by fitting calculated pH values to the observed values, using the method of least squares.

Conjugate acid/base pair

It is sometimes stated that "the conjugate of a weak acid is a strong base". Such a statement is incorrect. For example, acetic acid is a weak acid which has a = 1.75 x 10−5. Its conjugate base is the acetate ion with Kb = 10−14/Ka = 5.7 x 10−10 (from the relationship Ka × Kb = 10−14), which certainly does not correspond to a strong base. The conjugate of a weak acid is often a weak base and vice versa.

Acids in non-aqueous solvents

The strength of an acid varies from solvent to solvent. An acid which is strong in water may be weak in a less basic solvent, and an acid which is weak in water may be strong in a more basic solvent. According to Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, the solvent S can accept a proton.

For example, hydrochloric acid is a weak acid in solution in pure acetic acid, , which is more acidic than water.

The extent of ionization of the hydrohalic acids decreases in the order . Acetic acid is said to be a differentiating solvent for the three acids, while water is not.[6]: (p. 217)

An important example of a solvent which is more basic than water is dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO, . A compound which is a weak acid in water may become a strong acid in DMSO. Acetic acid is an example of such a substance. An extensive bibliography of values in solution in DMSO and other solvents can be found at Acidity–Basicity Data in Nonaqueous Solvents.

Superacids are strong acids even in solvents of low dielectric constant. Examples of superacids are fluoroantimonic acid and magic acid. Some superacids can be crystallised.[9] They can also quantitatively stabilize carbocations.[10]

Lewis acids reacting with Lewis bases in gas phase and non-aqueous solvents have been classified in the ECW model, and it has been shown that there is no one order of acid strengths.[11] The relative acceptor strength of Lewis acids toward a series of bases, versus other Lewis acids, can be illustrated by C-B plots.[12][13] It has been shown that to define the order of Lewis acid strength at least two properties must be considered. For the qualitative HSAB theory the two properties are hardness and strength while for the quantitative ECW model the two properties are electrostatic and covalent.

Factors determining acid strength

The inductive effect

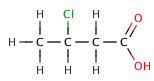

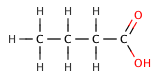

In organic carboxylic acids, an electronegative substituent can pull electron density out of an acidic bond through the inductive effect, resulting in a smaller value. The effect decreases, the further the electronegative element is from the carboxylate group, as illustrated by the following series of halogenated butanoic acids.

| Structure | Name | pKa |

|---|---|---|

|

2-chlorobutanoic acid | 2.86 |

|

3-chlorobutanoic acid | 4.0 |

|

4-chlorobutanoic acid | 4.5 |

|

butanoic acid | 4.5 |

Effect of oxidation state

In a set of oxoacids of an element, values decrease with the oxidation state of the element. The oxoacids of chlorine illustrate this trend.[6]: (p. 171)

| Structure | Name | Oxidation state |

pKa |

|---|---|---|---|

|

perchloric acid | 7 | -8† |

|

chloric acid | 5 | -1 |

| chlorous acid | 3 | 2.0 | |

|

hypochlorous acid | 1 | 7.53 |

† theoretical

References

- ^ Liang, Joan-Nan Jack (1976). The Hammett Acidity Function for Hydrofluoric Acid and some related Superacid Systems (Ph.D. Thesis) (PDF). Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University. p. 94.

- ^ Miessler G.L. and Tarr D.A. Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 1998, p.170) ISBN 0-13-841891-8

- ^ Porterfield, William W. Inorganic Chemistry (Addison-Wesley 1984) p.260 ISBN 0-201-05660-7

- ^ Trummal, Aleksander; Lipping, Lauri; Kaljurand, Ivari; Koppel, Ilmar A.; Leito, Ivo (2016). "Acidity of strong acids in water and dimethyl sulfoxide". J. Phys. Chem. A. 120 (20): 3663–3669. Bibcode:2016JPCA..120.3663T. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.6b02253. PMID 27115918.

- ^ Bell, R. P. (1973), The Proton in Chemistry (2nd ed.), Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

- ^ a b c Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-039913-7.

- ^ a b Guthrie, J.P. (1978). "Hydrolysis of esters of oxy acids: pKa values for strong acids". Can. J. Chem. 56 (17): 2342–2354. doi:10.1139/v78-385.

- ^ Martell, A.E.; Motekaitis, R.J. (1992). Determination and Use of Stability Constants. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-18817-4. Chapter 4: Experimental Procedure for Potentiometric pH Measurement of Metal Complex Equilibria

- ^ Zhang, Dingliang; Rettig, Stephen J.; Trotter, James; Aubke, Friedhelm (1996). "Superacid Anions: Crystal and Molecular Structures of Oxonium Undecafluorodiantimonate(V), [H3O][Sb2F11], Cesium Fluorosulfate, CsSO3F, Cesium Hydrogen Bis(fluorosulfate), Cs[H(SO3F)2], Cesium Tetrakis(fluorosulfato)aurate(III), Cs[Au(SO3F)4], Cesium Hexakis(fluorosulfato)platinate(IV), Cs2[Pt(SO3F)6], and Cesium Hexakis(fluorosulfato)antimonate(V), Cs[Sb(SO3F)6]". Inorg. Chem. 35 (21): 6113–6130. doi:10.1021/ic960525l.

- ^ George A. Olah, Schlosberg RH (1968). "Chemistry in Super Acids. I. Hydrogen Exchange and Polycondensation of Methane and Alkanes in FSO3H–SbF5 ("Magic Acid") Solution. Protonation of Alkanes and the Intermediacy of CH5+ and Related Hydrocarbon Ions. The High Chemical Reactivity of "Paraffins" in Ionic Solution Reactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 90 (10): 2726–7. doi:10.1021/ja01012a066.

- ^ Vogel G. C.; Drago, R. S. (1996). "The ECW Model". Journal of Chemical Education. 73: 701–707. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..701V. doi:10.1021/ed073p701.

- ^ Laurence, C. and Gal, J-F. Lewis Basicity and Affinity Scales, Data and Measurement, (Wiley 2010) pp 50-51 ISBN 978-0-470-74957-9

- ^ Cramer, R. E.; Bopp, T. T. (1977). "Graphical display of the enthalpies of adduct formation for Lewis acids and bases". Journal of Chemical Education. 54: 612–613. doi:10.1021/ed054p612. The plots shown in this paper used older parameters. Improved E&C parameters are listed in ECW model.

External links

- Titration of acids - freeware for data analysis and simulation of potentiometric titration curves

![{\displaystyle {\ce {H[SbF6]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81fc97f79d4c3d395f535e093347d7e531a3abdf)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {H[FSO3SbF5]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc571089e72c64e3866cc0dac118eeabe50708a3)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {H[CHB11Cl11]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90c05caa0a8732d637a5f63affde47aecf5a8030)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {H[FSO3]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bccda1d1c4b551781d4652eb6014aa363ea80da7)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {[H]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/570fdda794ab5f5775dc52489586e624583bbaa7)

![{\displaystyle K_{a}={\frac {[H^{+}][A^{-}]}{[HA]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/83ee86c6746a584bd7b209324db405b0563af917)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}T_{H}&=[H]+[HA]\\&=[H]+[A][H]/K_{a}\\&=[H]+[H]^{2}/K_{a}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d1d8921a76226cabb40caf4153fb742226ac0b6)

![{\displaystyle [H]^{2}/K_{a}+[H]-T_{H}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/20510aaf9a0ccaa6aa4bec6e7f9f6eb7222e8db9)