Ankle

| Ankle | |

|---|---|

Lateral view of the human ankle | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | articulatio talocruralis |

| MeSH | D000842 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.041 |

| TA2 | 165 |

| FMA | 9665 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The ankle joint is formed where the foot and the leg meet. The ankle, or talocrural joint, is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus bone in the foot.[1] The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than between the smaller fibula and the talus.

The term ankle is used to describe structures in the region of the ankle joint proper.[2]

Name derivation

The word ankle or ancle is common, in various forms, to Germanic languages, probably connected in origin with the Latin "angulus", or Greek "αγκυλος", meaning bent.

Evolution

It has been suggested that dexterous control of toes has been lost in favour of a more precise voluntary control of the ankle joint.[3]

Anatomy

Bones

The boney architecture of the ankle consists of three bones: the tibia, the fibula, and the talus. The articular surface of the tibia is referred to as the plafond. The medial malleolus is a boney process extending distally off the medial tibia. The distal-most aspect of the fibula is called the lateral malleolus. Together, the malleoli, along with their supporting ligaments, stabilize the talus underneath the tibia. The boney arch formed by the tibial plafond and the two malleoli is referred to as the ankle "mortise." The joint surface of all bones in the ankle are covered with articular cartilage.

Ligaments

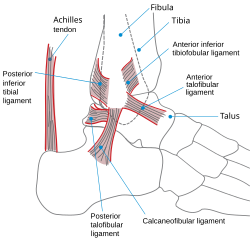

The ankle joint is bound by the strong deltoid ligament and three lateral ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament, the posterior talofibular ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament.

- The deltoid ligament supports the medial side of the joint, and is attached at the medial malleolus of the tibia and connect in four places to the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus, calcaneonavicular ligament, the navicular tuberosity, and to the medial surface of the talus.

- The anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments support the lateral side of the joint from the lateral malleolus of the fibula to the dorsal and ventral ends of the talus.

- The calcaneofibular ligament is attached at the lateral malleolus and to the lateral surface of the calcaneus.

Though it does not span across the ankle joint itself, the syndesmotic ligament makes an important contribution to the stability of the ankle. This ligament spans the syndesmosis, which is the term for the articulation between the medial aspect of the distal fibula and the lateral aspect of the distal tibia. An isolated injury to this ligament is often called a high ankle sprain.

The boney architecture of the ankle joint is most stable in dorsiflexion. Thus, a sprained ankle is more likely to occur when the ankle is plantar-flexed, as ligamentous support is more important in this position. The classic ankle sprain involves the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which is also the most commonly-injured ligament during inversion sprains. Another ligament that can be injured in a severe ankle sprain is the calcaneofibular ligament.

Disorders

Fractures

Symptoms of an ankle fracture can be similar to those of ankle sprains (pain), though typically they are often more severe by comparison. It is exceedingly rare for the ankle joint to dislocate in the presence of ligamentous injury alone.

The talus is most commonly fractured by two methods. The first is hyperdorsiflexion, where the neck of the talus is forced against the tibia and fractures. The second is jumping from a height - the body is fractured as the talus transmits the force from the foot to the lower limb bones.[4]

In the setting of an ankle fracture the talus can become unstable and subluxate or dislocate. People may complain of ecchymosis (bruising), or there may be an abnormal position, abnormal motion, or lack of motion. Diagnosis is typically by X-ray. Treatment is either via surgery or casting depending on the fracture types.

Footnotes

- ^ Template:EMedicineDictionary

- ^ Template:EMedicineDictionary

- ^ Brouwer B, Ashby P. (1992). Corticospinal projections to lower limb motoneurons in man. Exp Brain Res. 89(3):649-54. PMID 1644127

- ^ http://teachmeanatomy.net/lower-limb/bones/bones-of-the-foot-tarsals-metatarsals-and-phalanges/

References

- Anderson, Stephen A.; Calais-Germain, Blandine (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Chicago: Eastland Press. ISBN 0-939616-17-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McKinley, Michael P.; Martini, Frederic; Timmons, Michael J. (2000). Human Anatomy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-010011-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Marieb, Elaine Nicpon (2000). Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-4940-5.

External links

![]() Media related to Ankle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ankle at Wikimedia Commons

- "The Ankle". University of Glasgow. 2007. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Ardizzone, Remy; Valmassy, Ronald L. (October 2005). "How To Diagnose Lateral Ankle Injuries". Podiatry Today. Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Haddad, Steven L. (ed). "Foot & Ankle". You orthopaedic connection (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). Retrieved March 2010.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)