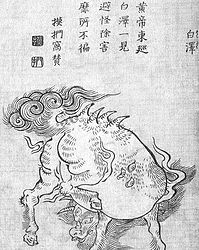

Bai Ze

Bai Ze (simplified Chinese: 白泽; traditional Chinese: 白澤; pinyin: Báizé) is a mythical creature from ancient Chinese legends, originating from Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海经). During the Tang Dynasty, it was introduced to Japan with its name unchanged. In the Book of Song (宋书) in China, there is a record related to Bai Ze called the Bái Zé Tú ‘diagram of (the deity) Baize’(白泽图): Bai Ze, the divine creature, knows all matters concerning ghosts and gods in the world. Entrusted by the Yellow Emperor, Bai Ze drew all the ghosts and spirits he knew into pictures and added annotations, which is the origin of the Bái Zé Tú.[1]

In the Ming Dynasty book SanCai TuHui (三才图会), Bai Ze’s appearance is described as having green hair on a loong head, with a horn growing on the top and the ability to fly. In the History of Yuan (元史), it is recorded as having the head of a tiger, red mane, loong’s body, and a horn. Bai Ze’s image in China combines features of both the loong and tiger.[2]

The only existing evidence related to Bái Zé Tú in China is an incomplete Dunhuang manuscript. It is said to have been copied in the 9th or 10th century and titled “Baize-jing guai—tu” ‘Bai Ze Diagrams of Spectral Prodigies’ (白泽精惟图), now kept at the National Library of France (P2682). This Dunhuang manuscript does not contain any drawings of Bai Ze. The term diagram(tu) in its title refers to the 11,520 drawings of ghosts and spirits depicted by Bai Ze in the legend.[1] [3]

In the folk beliefs of imperial China, Bai Ze also symbolized the ability to expel ghosts and ward off evil spirits.[4] According to the legend of Bai Ze, the remaining scrolls of the "Baize-jing guai—tu" recorded the signs of strange phenomena and evil spirits. It also detailed the disasters caused by these evil ghosts, as well as methods to avoid these calamities.[5] At the same time, besides serving as divination texts, according to Chinese records from the 9th to 10th centuries, there was a custom of hanging drawings of Bai Ze in households to protect against spirit-world harm, while Bai Ze diagram is also used to pray for the we-being and health of family members .[3]

In Japan[edit]

In Japan, Bai Ze is also called Hakutaku. The oldest known depiction of Hakutaku appears in the Tiandi ruixiang zhi ‘Treatise on the Auspicious Signs of Heaven and Earth’ (天地瑞祥志), a work originated in China. This work is listed in late 9th-century Japanese bibliographies, while is unknown in Chinese ones. In Tiandi ruixiang zhi, Hakutaku has the body of a cow and a human head with a beard. The “Hakutaku hi kai zu” image painted by Fukuhara Gogaku features three faces, each with three eyes and a pair of horns. By the 18th century, this depiction of Bai Ze had become standard in Japan, yet its origins remain uncertain. In “Hakutaku hi kai zu”, Hakutaku is depicted as a deity protecting people from evil spirits, so hanging Hakutaku’s diagram inside the house can ward off misfortune. There are extensive records in 18th and 19th century Japan of magical uses of Hakutaku, including protective talismans and for healing purposes. During the cholera epidemic in Edo in 1858, people were instructed to place Hakutaku’s image on their pillows before going to bed to protect themselves.[6]

In Zen and Japanese Culture, D. T. Suzuki describes the hakutaku as "a mythical creature whose body resembles a hand and whose head is human. It was anciently believed that the creature ate our bad dreams and evil experiences, and for this reason, people, wishing it to eat up all the ills which we are likely to suffer, used to hang its picture on the entrance gate or inside the house.[7]

Gallery[edit]

-

Baize by Toriyama Sekien

-

Portrait of the Bai Ze on a Ryūkyūan scroll painting by Gusukuma Seihō

-

Edo era Japanese illustration of Bai Ze

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b He 2013, pp. 50.

- ^ Chou 2016, pp. 48.

- ^ a b Harper 2018, pp. 214.

- ^ He 2013, pp. 53.

- ^ Sasaki 2012, pp. 74.

- ^ Harper 2018, pp. 215.

- ^ Suzuki 2010, pp. 168.

References[edit]

- Chou, Hsipo 周西波 (2016). "The Baize Cult and Its Changing Images 白澤信仰及其形像轉變". Studies on Tun-Huang 敦煌學. 32: 45–58. ISBN 978-986-88194-7-4.

- Harper, Donald (2018). "Hakutaku Hi Kai Zu". Asian Medicine (Leiden, Netherlands). 2: 50–53. ISSN 1573-4218.

- He, Lingxia 何凌霞 (2013). "A STUDY ON "BAIZE" "白泽"考论". Journal of Yunmeng 云梦学刊. 6: 50–53. ISSN 1006-6365.

- Sasaki, Satoshi 佐佐木聪 (2012). "Research on Original Dunhuang Manuscript Baize-jing guai—tu(P.2682) Kept at the National Library of France 法藏《白泽精惟图》(P.2682)". Dunhuang Research 敦煌研究. 3: 73–81. ISSN 1000-4106.

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitarō (2010). Zen and Japanese Culture. US: Princeton. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-691-14462-7.