Binary mass function

In astronomy, the binary mass function or simply mass function is a function that constrains the mass of the unseen component (typically a star or exoplanet) in a single-lined spectroscopic binary star or in a planetary system. It can be calculated from observable quantities only, namely the orbital period of the binary system, and the peak radial velocity of the observed star. The velocity of one binary component and the orbital period provide (limited) information on the separation and gravitational force between the two components, and hence on the masses of the components.

Introduction

The binary mass function follows from Kepler's third law when the radial velocity of one (observed) binary component is introduced.[1] Kepler's third law describes the motion of two bodies orbiting a common center of mass. It relates the orbital period (the time it takes to complete one full orbit) with the distance between the two bodies (the orbital separation), and the sum of their masses. For a given orbital separation, a higher total system mass implies higher orbital velocities. On the other hand, for a given system mass, a longer orbital period implies a larger separation and lower orbital velocities.

Because the orbital period and orbital velocities in the binary system are related to the masses of the binary components, measuring these parameters provides some information about the masses of one or both components.[2] But because the true orbital velocity cannot be determined generally, this information is limited.[1]

Radial velocity is the velocity component of orbital velocity in the line of sight of the observer. Unlike true orbital velocity, radial velocity can be determined from Doppler spectroscopy of spectral lines in the light of a star,[3] or from variations in the arrival times of pulses from a radio pulsar.[4] A binary system is called a single-lined spectroscopic binary if the radial motion of only one of the two binary components can be measured. In this case, a lower limit on the mass of the other (unseen) component can be determined.[1]

The true mass and true orbital velocity cannot be determined from the radial velocity because the orbital inclination is generally unknown. (The inclination is the orientation of the orbit from the point of view of the observer, and relates true and radial velocity.[1]) This causes a degeneracy between mass and inclination.[5][6] For example, if the measured radial velocity is low, this can mean that the true orbital velocity is low (implying low mass objects) and the inclination high (the orbit is seen edge-on), or that the true velocity is high (implying high mass objects) but the inclination low (the orbit is seen face-on).

Derivation for a circular orbit

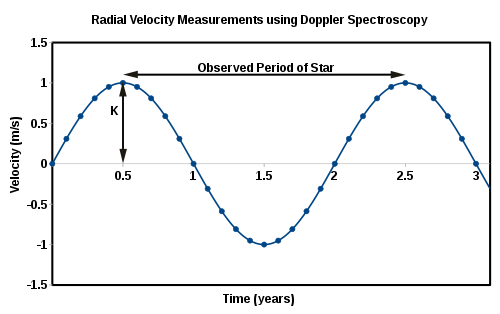

The peak radial velocity is the semi-amplitude of the radial velocity curve, as shown in the figure. The orbital period is found from the periodicity in the radial velocity curve. These are the two observable quantities needed to calculate the binary mass function.[2]

The observed object of which the radial velocity can be measured is taken to be object 1 in this article, its unseen companion is object 2.

Let and be the stellar masses, with the total mass of the binary system, and the orbital velocities, and and the distances of the objects to the center of mass. is the semi-major axis (orbital separation) of the binary system.

We start out with Kepler's third law, with the orbital frequency and the gravitational constant,

Using the definition of the center of mass location, ,[1] we can write

Inserting this expression for into Kepler's third law, we find

which can be rewritten to

The peak radial velocity of object 1, , depends on the orbital inclination (an inclination of 0° corresponds to an orbit seen face-on, an inclination of 90° corresponds to an orbit seen edge-on). For a circular orbit (orbital eccentricity = 0) it is given by[7]

After substituting we obtain

The binary mass function (with unit of mass) is[8][7][2][9][1][6][10]

For an estimated or assumed mass of the observed object 1, a minimum mass can be determined for the unseen object 2 by assuming . The true mass depends on the orbital inclination. The inclination is typically not known, but to some extent it can be determined from observed eclipses,[2] be constrained from the non-observation of eclipses,[8][9] or be modelled using ellipsoidal variations (the non-spherical shape of a star in binary system leads to variations in brightness over the course of an orbit that depend on the system's inclination).[11]

Limits

In the case of (for example, when the unseen object is an exoplanet[8]), the mass function simplifies to

In the other extreme, when (for example, when the unseen object is a high-mass black hole), the mass function becomes[2]

and since for , the mass function gives a lower limit on the mass of the unseen object 2.[6]

In general, for any or ,

Eccentric orbit

In an orbit with eccentricity , the mass function is given by[7][12]

Applications

X-ray binaries

If the accretor in an X-ray binary has a minimum mass that significantly exceeds the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit (the maximum possible mass for a neutron star), it is expected to be a black hole. This is the case in Cygnus X-1, for example, where the radial velocity of the companion star has been measured.[13][14]

Exoplanets

An exoplanet causes its host star to move in a small orbit around the center of mass of the star-planet system. This 'wobble' can be observed if the radial velocity of the star is sufficiently high. This is the radial velocity method of detecting exoplanets.[5][3] Using the mass function and the radial velocity of the host star, the minimum mass of an exoplanet can be determined.[15][16]: 9 [12][17] Applying this method on Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the solar system, led to the discovery of Proxima Centauri b, a terrestrial planet with a minimum mass of 1.27 ME.[18]

Pulsar planets

Pulsar planets are planets orbiting pulsars, and several have been discovered using pulsar timing. The radial velocity variations of the pulsar follow from the varying intervals between the arrival times of the pulses.[4] The first exoplanets were discovered this way in 1992 around the millisecond pulsar PSR 1257+12.[19] Another example is PSR J1719-1438, a millisecond pulsar whose companion, PSR J1719-1438 b, has a minimum mass approximate equal to the mass of Jupiter, according to the mass function.[8]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Karttunen, Hannu; Kröger, Pekka; Oja, Heikki; Poutanen, Markku & Donner, Karl J., eds. (2007) [1st pub. 1987]. "Chapter 9: Binary Stars and Stellar Masses". Fundamental Astronomy. Springer Verlag. pp. 221–227. ISBN 978-3-540-34143-7.

- ^ a b c d e Podsiadlowski, Philipp. "The Evolution of Binary Systems, in Accretion Processes in Astrophysics" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Radial Velocity – The First Method that Worked". The Planetary Society. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Binary Pulsar PSR 1913+16". Cornell University. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Brown, Robert A. (2015). "True Masses of Radial-Velocity Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 805 (2): 188. arXiv:1501.02673. Bibcode:2015ApJ...805..188B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/805/2/188. S2CID 119294767.

- ^ a b c Larson, Shane. "Binary Stars" (PDF). Utah State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c Tauris, T.M. & van den Heuvel, E.P.J. (2006). "Chapter 16: Formation and evolution of compact stellar X-ray sources". In Lewin, Walter & van der Klis, Michiel (eds.). Compact stellar X-ray sources. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 623–665. arXiv:astro-ph/0303456. ISBN 978-0-521-82659-4.

- ^ a b c d Bailes, M.; Bates, S. D.; Bhalerao, V.; Bhat, N. D. R.; Burgay, M.; Burke-Spolaor, S.; d'Amico, N.; Johnston, S.; et al. (2011). "Transformation of a Star into a Planet in a Millisecond Pulsar Binary". Science. 333 (6050): 1717–1720. arXiv:1108.5201. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1717B. doi:10.1126/science.1208890. PMID 21868629. S2CID 206535504.

- ^ a b van Kerkwijk, M. H.; Breton, M. P.; Kulkarni, S. R. (2011). "Evidence for a Massive Neutron Star from a Radial-velocity Study of the Companion to the Black-widow Pulsar PSR B1957+20". The Astrophysical Journal. 728 (2): 95. arXiv:1009.5427. Bibcode:2011ApJ...728...95V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/728/2/95. S2CID 37759376.

- ^ "Binary Mass Function". COSMOS – The SAO Encyclopedia of Astronomy, Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ "The Orbital Inclination". Yale University. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Boffin, H. M. J. (2012). "The mass-ratio distribution of spectroscopic binaries". In Arenou, F. & Hestroffer, D. (eds.). Proceedings of the workshop "Orbital Couples: Pas de Deux in the Solar System and the Milky Way". pp. 41–44. Bibcode:2012ocpd.conf...41B. ISBN 978-2-910015-64-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Mauder, H. (1973), "On the Mass Limit of the X-ray Source in Cygnus X-1", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 28: 473–475, Bibcode:1973A&A....28..473M

- ^ "Observational Evidence for Black Holes" (PDF). University of Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "Documentation and Methodology". Exoplanet Data Explorer. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Butler, R.P.; Wright, J. T.; Marcy, G. W.; Fischer, D. A.; Vogt, S. S.; Tinney, C. G.; Jones, H. R. A.; Carter, B. D.; et al. (2006). "Catalog of Nearby Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 646 (1): 505–522. arXiv:astro-ph/0607493. Bibcode:2006ApJ...646..505B. doi:10.1086/504701. S2CID 119067572.

- ^ Kolena, John. "Detecting Invisible Objects: a guide to the discovery of Extrasolar Planets and Black Holes". Duke University. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Anglada-Escudé, Guillem; Amado, Pedro J.; Barnes, John; et al. (2016). "A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri". Nature. 536 (7617): 437–440. arXiv:1609.03449. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..437A. doi:10.1038/nature19106. PMID 27558064. S2CID 4451513.

- ^ Wolszczan, D. A.; Frail, D. (9 January 1992). "A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257+12". Nature. 355 (6356): 145–147. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..145W. doi:10.1038/355145a0. S2CID 4260368.