Comparative cognition

Comparative cognition is the comparative study of the mechanisms and origins of cognition in various species, and is sometimes seen as more general than, or similar to, comparative psychology.[1] From a biological point of view, work is being done on the brains of fruit flies that should yield techniques precise enough to allow an understanding of the workings of the human brain on a scale appreciative of individual groups of neurons rather than the more regional scale previously used.[2] Similarly, gene activity in the human brain is better understood through examination of the brains of mice by the Seattle-based Allen Institute for Brain Science (see link below), yielding the freely available Allen Brain Atlas.[3] This type of study is related to comparative cognition, but better classified as one of comparative genomics. Increasing emphasis in psychology and ethology on the biological aspects of perception and behavior is bridging the gap between genomics and behavioral analysis.

In order for scientists to better understand cognitive function across a broad range of species they can systematically compare cognitive abilities between closely and distantly related species[4] Through this process they can determine what kinds of selection pressure has led to different cognitive abilities across a broad range of animals. For example, it has been hypothesized that there is convergent evolution of the higher cognitive functions of corvids and apes, possibly due to both being omnivorous, visual animals that live in social groups.[4] The development of comparative cognition has been ongoing for decades, including contributions from many researchers worldwide. Additionally, there are several key species used as model organisms in the study of comparative cognition.

Methodology

[edit]The aspects of animals which can reasonably be compared across species depend on the species of comparison, whether that be human to animal comparisons or comparisons between animals of varying species but near identical anatomies without a common ancestor. This comparison of cognitive trends can be observed in species across vast distances which feature similar biological features. Gross anatomical study as well as natural variation have been long considered aspects of comparative cognition.

Neurobiology

[edit]Current biological anthropology suggests that similarities in structures in the brain can, to an extent, be compared with certain aspects of behavior as their roots. However, it is difficult to quantify exactly which neuron connections are required for advanced function as opposed to basic reactionary cognitive operations, as identified in small insects or other small-brained organisms.[5] Regardless, circuitry common to a wide quantity of organisms has been identified, suggesting a convergence at least of the evolution of common neural Behavioral plasticity which allow for common functions and trends of inherited behavior.[6] It is possible that this is due to the size of the brain having direct correlation to the degree of function. However, it has been noted by experiments carried out on insects by Martin Giurfa in 2015, namely observing honey bees and fruit flies, which suggests that structures in the brain, regardless of size, can relate to functions and explain behavioral skills far greater than gross size can:[7]

As in larger brains, two basic neural architectural principles of many invertebrate brains are the existence of specialized brain structures and circuits, which refer to specific sensory domains, and of higher-order integration centres, in which information pertaining to these different domains converges and is integrated, thus allowing cross-talking and information transfer. These characteristics may allow positive transfer from a set of stimulus to novel ones, even if these belong to different sensory modalities. This principle appears crucial for certain tasks such as rule learning.

To this end, recent years have instead dedicated entirely to mapping signals and pathways of the brain in order to compare across species as opposed to using brain size. Further studies in this field are ongoing, especially as the process of tracking and stimulating neuron development changes.

Key contributors

[edit]Charles Darwin

[edit]Darwin initially suggested that humans and animals have similar psychological abilities in his 1871 publication The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, where he stated that animals also present behaviors associated with memory, emotion, and desires.[8] To Darwin, humans and animals shared the same mental cognition to varying degrees based on their place in the evolutionary timeline. This understanding of mental continuity between animals and humans form the basis of comparative cognition.[9]

Conwy Lloyd Morgan

[edit]In his 1894 publication An Introduction to Comparative Psychology, Morgan first postulated what would become known as Morgan's Cannon, which states that the behaviors of animals cannot be attributed to complex mechanisms when simpler mechanisms are possible.[10] Morgan's cannon criticized the work of his predecessors for being anecdotal and anthropomorphic, and proposed that certain intellectual animal behavior is more likely to have developed through multiple cycles of trial and error rather than spontaneously through some existing intelligence.[11] Morgan proposed that animals are capable of learning and their observed behavior is not purely the result of instinct or intrinsic mental function.

Edward J. Thorndike

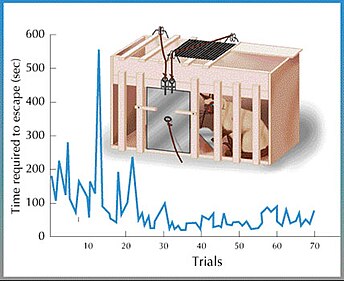

[edit]E.J Thorndike measured mental capacity as an organism's ability to form associations between their actions and the consequences of said actions.[10] In his 1898 publication Animal Intelligence: An Experimental Study of Associative Processes in Animals, Thorndike outlined his famous "puzzle box" experiments. Thorndike placed kittens inside a specialized box which contained a lever or button which, when triggered by the cat, would allow the cat to escape. Initially, the cats placed within the box would instinctively attempt to escape by randomly scratching the sides of the box. On some instances the cat would hit the lever, allowing their release. The next time this cat was placed within the box, it was able to conduct this trial and error routine again, however they were able to find the lever and release themselves more rapidly. Over multiple trials, all other behaviors that did not contribute to the cat's release were abandoned, and the cat was able to trigger the lever without error.[12] Thorndike's observations explored the extent to which animal's were capable of forming associations and learning from previous experiences, and he concluded that the animal cognition is homologous to the human cognition.[12] Thorndike's experiment established the field of comparative cognition and an experimental science and not simply a conceptual thought.[11] The progressive decrease in escape time observed by Thorndike's cats lead to his development of the Law of Effect, which states that actions and behaviors conducted by the organism which result in a benefit to the organism are more likely to be repeated.[10]

Ivan Pavlov

[edit]During his studies of digestive secretions in dogs, Pavlov recognized that the animals would begin to salivate as if in response to the presence of food, even when food has yet to be presented. He observed that the dogs has begun to associate the presence of the assistant carrying the food bowls with receiving food, and would salivate regardless of whether the food bowls would be given to them for feeding. He observed that the dogs has begun to associate the presence of the assistant carrying the food bowls with receiving food, and would salivate regardless of whether the food bowls would be given to them for feeding. Through this observation, Pavlov postulated that it may be possible to create novel response arcs, in which a previously neutral stimulus can be associated with an unconditioned stimulus, and will then trigger a similar or identical response as the initial response to the unconditioned stimulus.[10] The development of this response to a previously unknown stimuli became known as classical conditioning, and established that animal behavior is affected by the environmental conditions.[13]

Burrhus Frederic Skinner

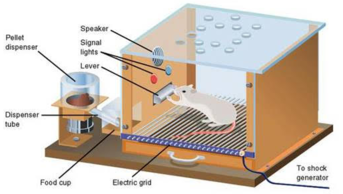

[edit]In his 1938 publication The Behavior of Organisms, B.F. Skinner coined the term operant conditioning to refer to the modification or development of specific voluntary behavior through the use of reinforcement and punishment. Reinforcement describes a stimulus which strengthens the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, while punishment describes a stimulus which weakens the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. Skinner designed his operant conditioning chamber, or "Skinner box", and used it to test the effects of reinforcement and punishment on voluntary behaviors. B.F. Skinner's observations extended the understanding of the Law of Effect presented by Thorndike to include the conditioning of responses through negative stimuli. Similar to Thorndike's "puzzle-box", Skinner's experiments demonstrated that when a voluntary behavior is met with a benefit, such as food, the behavior is more likely to be repeated. Skinner also demonstrated that when a voluntary behavior is met with a punishments', such as an electric shock, the behavior is less likely to be repeated.

Skinner further expanded his experiments to include negative and positive reinforcements and punishments. Positive reinforcements and punishments' involve the introduction of a positive stimulus or a negative stimulus respectively. Negative reinforcements and punishments involve the removal of negative stimulus or a positive stimulus respectively.

Wolfgang Kohler

[edit]Kohler criticized the work of Thorndike and Pavlov for emphasizing the mechanical approach to behavior while ignoring the cognitive approach. He opposed the suggestion that animals learn by simple trial and error, rather they learned through perception and insight. Kohler argued that Thorndike's puzzle-boxes presented no other method of escape except the method presented by the experiment as "correct", and in doing-so the cognitive problem solving abilities of the animal are rendered useless. He suggested that if the subjects were able to observe the apparatus itself, they would be able to deduce methods of escape by perceiving the situation and the environment. Kohler's views were influenced by the observations he made when studying the behaviors of chimpanzees in Tenerife, Spain. Kohler noted that the primates were capable of insight, utilizing various familiar objects from their environment to solve complex problems, such as utilizing tools to reach out of reach items.[10]

Karl Von Frisch

[edit]

Karl von Frisch studied the "waggle dances" of bee populations. When foraging bees returned to the hive from a food source, they would perform complex, figure eight patterns. Through these observations, von Frisch established that bees were not only capable of recalling spatial memories, but were also able to communicate these memories to other members of the species symbolically. His research also established that other bees were capable of interpreting the information and apply it to their environment and behaviors.[14]

Allen and Beatrix Gardner

[edit]The Gardners are famously known for their raising of Washoe the chimpanzee, and their teaching of American Sign Language to Washoe. Researchers have long questioned whether primates, the evolutionary cousins of humans, could be taught to communicate through human speech. While communication through verbal language is not possible, it was hypothesized that sign language could be utilized. The Gardners designed a specialized method which they referred to as cross-fostering, in which they raised Washoe from infancy in a human cultural and social environment, allowing for a comparative analysis of language acquisition in human children and primates. After 51 months of teaching, the Gardners reported that Washoe has 132 signs.[15] Through the methods of the Gardners, Washoe was able to learn to communicate in American sign language, and demonstrated the ability to create novel signs for new factors introduced to her environment. In one instance, Washoe described a Brazil nut, an object whose name she was not familiar with, by signing "rock" and "berry", and continued to refer to the Brazil nut in this way. Washoe also learned how to communicate new information to her handlers. For example, after being asked what was wrong, Washoe was able to indicate a feeling of sickness by signing "hurt" near her stomach. It was later shown that she had contracted an intestinal flu.[16] In another, Washoe had lost a toy and successfully told her handlers of its location and asked for them to retrieve it for her.[15] The Gardners' studies proved that primates are capable of language acquisition, as well as language development and expression of private information through the use of a language similar to human communication.

Model organisms

[edit]Canines

[edit]Famously used in Ivan Pavlov's classical conditioning experiments, members of the canine family have long been considered a primary model organism for comparative cognition studies. Many other psychologists have utilized canines in their studies. C.L. Morgan referred to his terrier Tony when developing his Cannon,[10] and Thorndike recreated his puzzle-box experiments with dogs as well. Members of this family have been domesticated for much of human history, and in many instances the behaviors of humans have co-evolved alongside these domesticated dogs. It has been hypothesized that this evolutionary relationship between humans and dogs has contributed to the development of complex cognitive behaviors that can be used to study the unique cognitive abilities of canines.[17]

Felines

[edit]As another historical companion to humans, felines have co-evolved along with the human species. Use of felines in the study of comparative cognition is most associated with the work of Thorndike and his puzzle-boxes.[12]

Rodents

[edit]Rodents such as various species of rats have been used in the experiments of B.F Skinner, as well as others studying comparative cognition, due to the abundance of cognitive similarity between rodents and humans. It has been shown that rodents, specifically rats, and humans present similar memorization and mnemonic processes, as both humans and rodents display primacy and recency effects when tasked with the recollection of numbered items. There is also evidence to support that both rats and humans share similar attentional processes, as they are both able to demonstrate sustained, selective and divided attention.[18]

Corvids

[edit]Corvids have received a lot of attention from the comparative cognition community in the twenty-first century, specifically the species of corvids known as New Caledonian crows. Several populations of this species, located on islands in the New Caledonian archipelago have demonstrated the ability to create and utilize tools to manipulate their environment for their benefit. These crows were observed to modify the ribs of palm leaves by nibbling the ends to resemble a hook, and proceeded to use these tools to reach prey and food in previously inaccessible areas, such as small cracks within trees. It has also been observed that this technique of creating tools has been passed onto future generations[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Beran, Michael J.; Parrish, Audrey E.; Perdue, Bonnie M.; Washburn, David A. (2014-01-01). "Comparative Cognition: Past, Present, and Future". International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 27 (1): 3–30. doi:10.46867/ijcp.2014.27.01.07. ISSN 0889-3667. PMC 4239033. PMID 25419047.

- ^ Greenspan, Ralph J.; van Swinderen, Bruno (December 2004). "Cognitive consonance: complex brain functions in the fruit fly and its relatives". Trends in Neurosciences. 27 (12): 707–711. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.002. ISSN 0166-2236. PMID 15541510. S2CID 15780859.

- ^ "Brain Map - brain-map.org". portal.brain-map.org. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ^ a b van Horik, Jayden; Emery, Nathan J. (2011-11-01). "Evolution of cognition". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2 (6): 621–633. doi:10.1002/wcs.144. ISSN 1939-5086. PMID 26302412.

- ^ Chittka, Lars; Niven, Jeremy (2009-11-17). "Are bigger brains better?". Current Biology. 19 (21): R995 – R1008. Bibcode:2009CBio...19.R995C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.023. ISSN 1879-0445. PMID 19922859. S2CID 7247082.

- ^ Chittka, Lars; Rossiter, Stephen J.; Skorupski, Peter; Fernando, Chrisantha (2012). "What is comparable in comparative cognition?". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 367 (1603): 2677–2685. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0215. ISSN 0962-8436. JSTOR 41739990. PMC 3427551. PMID 22927566.

- ^ Giurfa, Martin (2015-03-21). "Learning and cognition in insects". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 6 (4): 383–395. doi:10.1002/wcs.1348. ISSN 1939-5078. PMID 26263427.

- ^ Shettleworth, S.J. (529–546). Darwin, Tinbergen, and the evolution of comparative cognition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wasserman, E.A. (1993). "Comparative Cognition: Beginning the second century of the study of animal intellegence". Psychology Bulletin. 113 (2): 211–228. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.2.211.

- ^ a b c d e f Roitblat, Herbert L. (1987). Introduction to Comparative Cognition. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ a b Olmstead; Kuhlmier, Mary; Valerie (2015). Comparative Cognition. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Thorndike, Edward J. (1898). "Animal Intelligence: An experimental study of associative processes in animals". The Psychological Review: Series of Monograph Supplements. 2 (4).

- ^ a b Shuttleworth, Sara J. Fundamentals of Comparative Cognition. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Menzel, R. (2019). "The Waggle Dance as an Intended Flight: A Cognitive Perspective". Insects. 10 (12): 424. doi:10.3390/insects10120424. PMC 6955924. PMID 31775270.

- ^ a b White Miles, H.L. (1991). "Book Review: Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees". International Journal of Primatology. 12 (3): 303–307. doi:10.1007/BF02547591. S2CID 37680550.

- ^ Fouts, Roger S., Mellgren, Roger R. (1976). "Language, signs, and cognition in the chimpanzee". Sign Language Studies. 13: 319–346. doi:10.1353/sls.1976.0004. S2CID 144586199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feuerbacher, Erica N., Wynne, C.D.L. (2011). "A History of Dogs as Subjects in North American Experimental Psychological Research". Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews. 6: 46–71. doi:10.3819/ccbr.2011.60001. hdl:10919/81791.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steckler, T., Muir, J.L. (1995). "Measurement of cognitive function: relating rodent performance with human minds". Cognitive Brain Research. 3 (3–4): 299–308. doi:10.1016/0926-6410(96)00015-8. PMID 8806031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Trends in Neurosciences Article on Insect Cognition

- Nature: Inside the Animal Mind

- Article on Empathy in Elephants

- APA article on Abstract Thinking in Baboons

- APA article on Short Term Memory in Honeybees

- University of Alberta's Comparative Cognition and Behavior Page

- Comparative Cognition Lab at Cambridge University

- The Comparative Cognition Society

- Allen Institute for Brain Science