Culture of Shiraz

The culture of Shiraz concerns the arts, music, museums, festivals, many Persian entertainments and sports activities in Shiraz, the capital of Fars Province. Shiraz is known as the city of poets, gardens, wine, nightingales and flowers.[1][2] The crafts of Shiraz consist of inlaid mosaic work of triangular design; silver-ware; carpet-weaving, and the making of the rugs called gilim (Shiraz Kilim), and blankets called Jajim found in the villages and among the tribes.

According to some sources, Shiraz is the heartland of Persian culture.[3]

The garden is an important part of Iranian culture. There are many old gardens in Shiraz such as the Eram garden and the Afif abad garden. According to some people, Shiraz "disputes with Xeres (or Jerez) in Spain the honour of being the birthplace of sherry."[4] Shirazi wine originates from the city; however, under the current Islamic regime, alcohol is prohibited except for religious minorities.[5]

Shiraz is proud of being mother land of Hafiz Shirazi, Shiraz is a center for Iranian culture and has produced a number of famous poets. Saadi, a 12th- and 13th-century poet was born in Shiraz. He left his native town at a young age for Baghdad to study Arabic literature and Islamic sciences at Al-Nizamiyya of Baghdad. When he reappeared in his native Shiraz he was an elderly man. Shiraz, under Atabak Abubakr Sa'd ibn Zangy (1231–1260) was enjoying an era of relative tranquility. Saadi was not only welcomed to the city but he was highly respected by the ruler and enumerated among the greats of the province. He seems to have spent the rest of his life in Shiraz. Hafiz, another famous poet and mystic was also born in Shiraz. A number of scientists also originate from Shiraz. Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, a 13th-century astronomer, mathematician, physician, physicist and scientist was from Shiraz. In his The Limit of Accomplishment concerning Knowledge of the Heavens, he also discussed the possibility of heliocentrism.[6]

Cuisine[edit]

There are many restaurants and cafes in Shiraz, both modern and classic, serving both Iranian and cosmopolitan cuisine. Shiraz wine is famous both in Iran and in the world. By the ninth century, the city of Shiraz had already established a reputation for producing the finest wine in the world,[7] and was the "Iran's wine capital". The export of Shiraz wine by European merchants in the 17th century has been documented. As described by enthusiastic English and French travellers to the region in the 17th to 19th centuries, the wine grown close to the city was of a more dilute character due to irrigation, while the best Shiraz wines were actually grown in terraced vineyards around the village of Khollar. These wines were white and existed in two different styles: dry wines for drinking young, and sweet wines meant for aging. The latter wines were compared to "an old sherry" (one of the most prized European wines of the day), and at five years of age were said to have a fine bouquet and nutty flavour. The dry white Shiraz wines (but not the sweet ones) were fermented with significant stem contact, which should have made these wines rather phenolic, i.e., rich in tannins.[7]

Shirazi salad (Persian: سالاد شیرازی sālād shirāzi) is an Iranian salad that originated from and is named after Shiraz. It is a relatively modern dish, dating to sometime after the introduction of the tomato to Iran at the end of the nineteenth century.[8] Its primary ingredients are cucumber, tomato, onion, olive oil, herbal spices and verjuice, although lime juice is sometimes used in its preparation.[9] Shirazi faloodeh (or Paloodeh) (Persian: پالوده شیرازی, romanized: pālūde Shirāzi) is a special version of Faloodeh from the city of Shiraz, is particularly well-known.[10]

Festivals and holidays[edit]

Iranian festivals[edit]

Nowruz[edit]

Iran's official New Year begins with Nowruz, an ancient Iranian tradition celebrated annually on the vernal equinox. It is enjoyed by people adhering to different religions, but is considered a holiday for the Zoroastrians. It was registered on the UNESCO's list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2009,[11] described as the Persian New Year,[12][13][14][15] Shiraz Municipality organizes festivals during Nowruz. During Nowruz, many tourists visit the city and Nowruz is one of the best times for visiting Shiraz. On Nowruz, Shiraz attracts a large number of foreign and Iranian tourists.[16]

-

City during Nowruz

-

Eram Garden (Shiraz historic Persian garden) during Nowruz

-

Eram Garden (Shiraz historic Persian garden) during Nowruz

Chaharshanbe Suri[edit]

Chaharshanbe Suri is one of the most popular festivals in Shiraz. On the eve of the last Wednesday of the preceding year, as a prelude to Nowruz, the ancient festival of Čāršanbe Suri celebrates Ātar ("Fire") by performing rituals such as jumping over bonfires and lighting off firecrackers and fireworks.[17][18]

Sizdah Be-dar[edit]

On this day, the people of Shiraz enjoy the green space and parks of the city. The Nowruz celebrations last by the end of the 13th day of the Iranian year (Farvardin 13, usually coincided with 1 or 2 April), celebrating the festival of Sizdebedar, during which the people traditionally go outdoors to picnic.[citation needed]

Mehregan[edit]

Mehregan that is also widely referred to as the Persian Festival of Autumn[19][20][21] is a Zoroastrian and Persian festival that has been preserved in Shiraz for centuries.[22][23]

Fashion and clothing[edit]

Shiraz traditional clothes usually have "happy" colors. In some sources it is mentioned as a symbol of peace and happiness.[24]

-

Traditional clothing of the province

-

Street fashion of the city (2018)

-

Shirazi modeling with Western clothing (2020)

-

Common clothes in 2012.

Sports and athletics[edit]

Soccer is the most popular sport in Shiraz and the city has many teams in this sport. The most notable of these teams is Bargh Shiraz who are one of the oldest teams in Iran, Bargh was once a regular member of the Persian Gulf Pro League; however, financial issues and poor management have led them dropping to League 3 where they currently play. Shiraz's other major football team is Fajr Sepasi who also played in the Persian Gulf Pro League; however, now they play in the second tier Azadegan League. Shiraz is host to a number of smaller and lesser known teams as well, such as Kara Shiraz, New Bargh and Qashaei who all play in League 2.

The main sporting venue in Shiraz is Hafezieh Stadium which can hold up to 20,000 people. The stadium is the venue for many of the cities football matches and has occasionally hosted the Iran national football team. Shiraz is also home to another stadium, Pars Stadium, which have been completed in 2017 and can host up to 50,000 spectators.

Music and dance[edit]

Shiraz hosts music concerts by famous Iranian artists. Although there is no standard concert hall in Shiraz.[25]

Museums and galleries[edit]

The most visited museum in Shiraz is the Pars Museum. it is located in Nazar Garden. It is also the burial place of Karim Khan Zand.[26]

Religion[edit]

Most of the population of Shiraz are Muslims. Shiraz also was home to a 20,000-strong Jewish community, although most emigrated to the United States and Israel in the latter half of the 20th century.[27] There are currently only two functioning churches in Shiraz, one Armenian, the other, Anglican.[28][29]

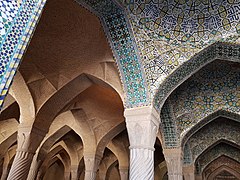

-

Moshir Mosque

References[edit]

- ^ "Iranian Cities: Shiraz". Iranchamber.com. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Shiraz". Asemangasht.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Shiraz, heartland of Persian culture". IRNA English. 2015-09-22. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ^ "Shiraz". Asemangasht.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "Shiraz City info (culture and lifestyle)". aboutshiraz.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- ^ A. Baker and L. Chapter (2002), "Part 4: The Sciences". In M. M. Sharif, “A History of Muslim Philosophy”, Philosophia Islamica.

- ^ a b Entry on "Persia" in J. Robinson (ed), "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, p. 512-513, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ^ Chehabi, H. E. (2003-03-01). "The Westernization of Iranian Culinary Culture". Iranian Studies. 36 (1): 43–61. doi:10.1080/021086032000062875. ISSN 0021-0862. S2CID 162389157.

- ^ Raichlen, S. (2008). The Barbecue! Bible 10th Anniversary Edition. Workman Publishing Company. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7611-5957-5.

- ^ Marks, Gil (2010-11-17). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Wiley. ISBN 9780544186316.

- ^ "Proclamation of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity (2001–2005) – intangible heritage – Culture Sector – UNESCO". Unesco.org. 2000. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "Norouz Persian New Year". British Museum. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "General Assembly Fifty-fifth session 94th plenary meeting Friday, 9 March 2001, 10 a.m. New York" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 9 March 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "Nowrooz, a Persian New Year Celebration, Erupts in Iran – Yahoo!News". News.yahoo.com. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "US mulls Persian New Year outreach". Washington Times. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "فارس درصدرجدول ازنظر شمارمسافران نوروزي و كيفيت ميزباني". ایرنا (in Persian). 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ^ "Call for Safe Yearend Celebration". Financial Tribune. 12 March 2017.

The ancient tradition has transformed over time from a simple bonfire to the use of firecrackers...

- ^ "Light It Up! Iranians Celebrate Festival of Fire". NBC News. 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Mehrgan, Persian Festival of Autumn, at Orange County Fair & Expo Center: September 9-10, 2006". Payvand News. 2006-08-21. Archived from the original on 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Persian-Dutch Community celebrated "MEHREGAN", Persian Festival of Autumn". Persian Dutch Network. 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ Bahrami, Askar, Jashnha-ye Iranian, Tehran, 1383, p. 35.

- ^ Stausberg, Michael; Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, Yuhan (2015). "The Iranian festivals: Nowruz and Mehregan". The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 494–495. ISBN 978-1118786277.

- ^ "آيين جشن مهرگان در شيراز برگزار شد". ایرنا (in Persian). 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "لزوم توجه به لباسهای محلی ایرانی". ایرنا (in Persian). 2004-11-08. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "تالار مرکزی شیراز در بنبست/ بسته تشویقی هم کارساز نشد". خبرگزاری مهر | اخبار ایران و جهان | Mehr News Agency (in Persian). 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ Pars Museum, KolahFarangi Mansion. M. Rostami (ISBN 978-600-91247-0-1), p. 9

- ^ Huggler, Justin (4 June 2000). "Jews accused of spying are pawns in Iran power struggle". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Tait, Robert (27 December 2005). "Bearing the cross". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Iranian Monuments: Historical Churches in Iran". Iranchamber.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 5 May 2011.