Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit | |

|---|---|

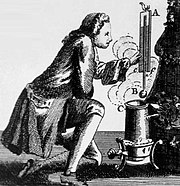

Fahrenheit, the originator of the era of precision thermometry | |

| Born | 24 May 1686 (14 May Old Style) Danzig (Gdańsk), Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| Died | 16 September 1736 (aged 50) |

| Known for | Precision thermometry Alcohol thermometer Mercury-in-glass thermometer (first widely used, reliable thermometer) Fahrenheit scale (first widely used standardized temperature scale) Fahrenheit hydrometer |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics (thermometry) |

| Signature | |

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit FRS (/ˈfærənhaɪt/; German: [ˈfaːʁənhaɪt]; 24 May 1686 – 16 September 1736)[1] was a physicist, inventor, and scientific instrument maker. Fahrenheit was born in Danzig (Gdańsk), then a predominantly German-speaking city in the Pomeranian Voivodeship of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He later moved to the Dutch Republic at age 15, where he spent the rest of his life (1701–1736) and was one of the notable figures in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology.

A pioneer of exact thermometry,[2] he helped lay the foundations for the era of precision thermometry by inventing the mercury-in-glass thermometer (first widely used, practical, accurate thermometer) and Fahrenheit scale (first standardized temperature scale to be widely used).[3] In other words, Fahrenheit's inventions ushered in the first revolution in the history of thermometry (branch of physics concerned with methods of temperature measurement). From the early 1710s until the beginnings of the electronic era, mercury-in-glass thermometers were among the most reliable and accurate thermometers ever invented.[4]

Biography

Fahrenheit was born in Danzig (Gdańsk), then in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but lived most of his life in the Dutch Republic. The Fahrenheits were a German Hanse merchant family who had lived in several Hanseatic cities. Fahrenheit's great-grandfather had lived in Rostock, and research suggests that the Fahrenheit family originated in Hildesheim.[5] Daniel's grandfather moved from Kneiphof in Königsberg (present-day Kaliningrad) to Danzig and settled there as a merchant in 1650. His son, Daniel Fahrenheit (the father of Daniel Gabriel), married Concordia Schumann, daughter of a well-known Danzig business family. Daniel was the eldest of the five Fahrenheit children (two sons, three daughters) who survived childhood. His sister, Virginia Elisabeth Fahrenheit, married Benjamin Krüger and was the mother of Benjamin Ephraim Krüger, a clergyman and playwright.[6]

Daniel Gabriel began training as a merchant in Amsterdam after his parents died on 14 August 1701 from eating poisonous mushrooms. However, Fahrenheit's interest in natural science led him to begin studies and experimentation in that field. From 1717, he traveled to Berlin, Halle, Leipzig, Dresden, Copenhagen, and also to his hometown, where his brother still lived. During that time, Fahrenheit met or was in contact with Ole Rømer, Christian Wolff, and Gottfried Leibniz. In 1717, Fahrenheit settled in The Hague as a glassblower, making barometers, altimeters, and thermometers. From 1718 onwards, he lectured in chemistry in Amsterdam. He visited England in 1724 and was the same year elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[7] From August 1736 Fahrenheit stayed in the house of Johannes Frisleven at Plein square in The Hague, in connection with an application for a patent at the States of Holland and West Friesland. At the beginning of September he became ill and on the 7th his health had deteriorated to such an extent that he had notary Willem Ruijsbroek come to draw up his will. On the 11th the notary came by again to make some changes. Five days after that Fahrenheit died at the age of fifty. Four days later he received the fourth-class funeral of one who is classified as destitute, in the Kloosterkerk in The Hague (the Cloister or Monastery Church).[8][9][10]

Fahrenheit scale

According to Fahrenheit's 1724 article,[11][12] he determined his scale by reference to three fixed points of temperature. The lowest temperature was achieved by preparing a frigorific mixture of ice, water, and a salt ("ammonium chloride or even sea salt"), and waiting for the eutectic system to reach equilibrium temperature. The thermometer then was placed into the mixture and the liquid in the thermometer allowed to descend to its lowest point. The thermometer's reading there was taken as 0 °F. The second reference point was selected as the reading of the thermometer when it was placed in still water when ice was just forming on the surface.[13] This was assigned as 30 °F. The third calibration point, taken as 90 °F, was selected as the thermometer's reading when the instrument was placed under the arm or in the mouth.[14]

Fahrenheit came up with the idea that mercury boils around 300 degrees on this temperature scale. Work by others showed that water boils about 180 degrees above its freezing point. The Fahrenheit scale later was redefined to make the freezing-to-boiling interval exactly 180 degrees,[11] a convenient value as 180 is a highly composite number, meaning that it is evenly divisible into many fractions. It is because of the scale's redefinition that normal mean body temperature today is taken as 98.2 degrees,[15] whereas it was 96 degrees on Fahrenheit's original scale.[16]

The Fahrenheit scale was the primary temperature standard for climatic, industrial and medical purposes in English-speaking countries until the 1970s, nowadays replaced by the Celsius scale long used in the rest of the world, apart from the United States, where temperatures and weather reports are still broadcast in Fahrenheit.[17]

-

Thermometer with Fahrenheit (symbol °F) and Celsius (symbol °C) units. The application of mercury (1714) and Fahrenheit scale (1724) for liquid-in-glass thermometers ushered in a new era of accuracy and precision in thermometry.

-

The Celsius and Fahrenheit scales

-

A medical mercury-in-glass maximum thermometer. Daniel Fahrenheit's mercury-in-glass thermometer was far more reliable and accurate than any that had existed before, and the mercury thermometers in use today are made in the way Fahrenheit devised

-

Memorial plaque at Fahrenheit's burial site in The Hague

See also

References

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Grigull, Ulrich (1966). Fahrenheit, a Pioneer of Exact Thermometry. (The Proceedings of the 8th International Heat Transfer Conference, San Francisco, 1966, Vol. 1, pp. 9–18.)

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "Science & Technology: Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit"

- ^ Knake, Maria (April 2011). "The Anatomy of a Liquid-in-Glass Thermometer". AASHTO re:source, formerly AMRL (aashtoresource.org). Retrieved 4 August 2018.

For decades mercury thermometers were a mainstay in many testing laboratories. If used properly and calibrated correctly, certain types of mercury thermometers can be incredibly accurate. Mercury thermometers can be used in temperatures ranging from about -38 to 350°C. The use of a mercury-thallium mixture can extend the low-temperature usability of mercury thermometers to -56°C. (...) Nevertheless, few liquids have been found to mimic the thermometric properties of mercury in repeatability and accuracy of temperature measurement. Toxic though it may be, when it comes to LiG [Liquid-in-Glass] thermometers, mercury is still hard to beat.

- ^ Kant, Horst (1984). G. D. Fahrenheit / R. -A. F. de Réaumur / A. Celsius. B. G. Teubner. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ^ See the Fahrenheit and Krueger genealogies.

- ^ "The Royal Society Archive catalogue". Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Star, Pieter van der: Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit's Letters to Leibniz and Boerhaave. Rodopi Publishers, Amsterdam 1983. ISBN 9062920675

- ^ "The Kloosterkerk". The Kloosterkerk. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Zuiden, D.S. van: Het Testament en de Inboedel van Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, in: “Oud-Holland”, pp. 123-130, Binger Publishers, Amsterdam 1913

- ^ a b "Fahrenheit temperature scale". Sizes, Inc. 10 December 2006. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Fahrenheit describes, in Latin, these numerical choices in the following paper: Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724). "Experimenta et Observationes de Congelatione aquae in vacuo factae". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 33 (381–391): 78–84. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0016.

- ^ Heath, Jonathan. "Why does the Fahrenheit scale use 32 degrees as a freezing point?". PhysLink. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ Burdge, Julia (10 January 2014). Chemistry: Atoms First. McGraw-Hill. p. 11. ISBN 9780077646479. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ MacKowiak, Philip A. (1992). "A Critical Appraisal of 98.6°F, the Upper Limit of the Normal Body Temperature, and Other Legacies of Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 268 (12): 1578–80. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490120092034. PMID 1302471.

- ^ Elert, Glenn; Forsberg, C; Wahren, LK (2002). "Temperature of a Healthy Human (Body Temperature)". Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 16 (2): 122–8. doi:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00069.x. PMID 12000664. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ Zimmermann, Kim Ann (24 September 2013). "Fahrenheit: Facts, History & Conversion Formulas". Retrieved 16 September 2017.

Further reading

- Bolton, Henry Carrington (1900). Evolution of the Thermometer, 1592–1743. Easton, Pennsylvania: The Chemical Publishing Company. pp. 66–79.

- Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724). "Experimenta circa gradum caloris liquorum nonnullorum ebullientium instituta (Experiments done on the degree of heat of a few boiling liquids)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 33 (381): 1–3. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0002.

- Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724). "Experimenta et Observationes de Congelatione aquae in vacuo factae". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 33 (381–391): 78–84. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0016. (Latin)

- Klemm, Friedrich (1959), "Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 746–747

- Kops, J (1976). "Who was G.D. Fahrenheit?". Zdravotnická Pracovnice. Vol. 26, no. 2 (published February 1976). pp. 118–19. PMID 775856. (Czech)

- Lommel (1877), "Fahrenheit, Gabriel Daniel", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 6, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, p. 535

- Friedrich Klemm (1959), "Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 746–747

- Middleton, W. E. Knowles (1966). A History of the Thermometer and its Use in Meteorology. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Sorokina, T S (1986). "Creators of medical thermometry (on the 300th anniversary of the birth of Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit—24 May 1686 and on the 350th anniversary of the death of Santorio Santorio—22 February 1636)". Klinicheskaia Meditsina. Vol. 64, no. 10 (published October 1986). pp. 147–51. PMID 3543477. (Russian)

- Van Der Star, P., ed. (1984). Fahrenheit's Letters to Leibniz and Boerhaave. Editions Rodopi.

External links

- Letter from Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (scan) to Carl Linnaeus, 7 May 1736 n.s., [1] (in German)

- Senese, Fred (2005). "Why isn't 0°F the lowest possible temperature for a salt/ice/water mixture?".

- Fahrenheit's papers in the Royal Society Publishing (in Latin)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.