Donatello

Donatello | |

|---|---|

Donatello, in a 15th-century portrait by Paolo Uccello | |

| Born | Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi c. 1386 |

| Died | 13 December 1466 (aged 79–80) Republic of Florence |

| Nationality | Florentine |

| Education | Lorenzo Ghiberti |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | Saint George, David, Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386 – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello (English: /ˌdɒnəˈtɛloʊ/[1] Italian: [donaˈtɛllo]), was a Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance style in sculpture. He spent time in other cities, and while there he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy his techniques, developed in the course of a long and productive career. Financed by Cosimo de' Medici, Donatello's David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity.

He worked with stone, bronze, wood, clay, stucco, and wax, and had several assistants, with four perhaps being a typical number. Although his best-known works mostly were statues in the round, he developed a new, very shallow, type of bas-relief for small works, and a good deal of his output was larger architectural reliefs.

Early life

Donatello was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, who was a member of the Florentine Arte della Lana. He was born in Florence, probably in the year 1386. Donatello was educated in the house of the Martelli family.[2] He apparently received his early artistic training in a goldsmith's workshop,[citation needed] and then worked briefly in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti.[3]

In Pistoia in 1401, Donatello met the older Filippo Brunelleschi. They likely went to Rome together around 1403, staying until the next year, to study the architectural ruins. Brunelleschi informally tutored Donatello in goldsmithing and sculpture.[4] Brunelleschi's buildings and Donatello's sculptures are both considered supreme expressions of the spirit of this era in architecture and sculpture, and they exercised a potent influence upon the artists of the age.

Work in Florence

In Florence, Donatello assisted Lorenzo Ghiberti with the statues of prophets for the north door of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, for which he received payment in November 1406 and early 1408. In 1409–1411 he executed the colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist, which occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade until 1588, and now is placed in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo. This work marks a decisive step forward from late Gothic Mannerism in the search for naturalism and the rendering of human feelings.[5] The face, the shoulders, and the bust are still idealized, while the hands and the fold of cloth over the legs are more realistic.

In 1411–1413, Donatello worked on a statue of St. Mark for the guild church of Orsanmichele. In 1417 he completed the Saint George for the Confraternity of the Cuirass-makers. From 1423 is the Saint Louis of Toulouse for the Orsanmichele, now in the Museum of the Basilica di Santa Croce. Donatello also sculpted the classical frame for this work, which remains, while the statue was moved in 1460 and replaced by the Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Verrocchio.

Between 1415 and 1426, Donatello created five statues for the campanile of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, also known as the Duomo. These works are the Beardless Prophet; Bearded Prophet (both from 1415); the Sacrifice of Isaac (1421); Habbakuk (1423–25); and Jeremiah (1423–26); which follow the classical models for orators and are characterized by strong portrait details. From the 1420's is the Pazzi Madonna relief in Berlin. In 1425, he executed the notable Crucifix for Santa Croce; this work portrays Christ in a moment of agony, eyes, and mouth partially opened, the body contracted in an ungraceful posture.

From 1425 to 1427, Donatello collaborated with Michelozzo on the funerary monument of the Antipope John XXIII for the Battistero in Florence. Donatello made the recumbent bronze figure of the deceased, under a shell. In 1427, he completed in Pisa a marble relief for the funerary monument of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci at the church of Sant'Angelo a Nilo in Naples. In the same period, he executed the relief of The Feast of Herod (c. 1427) and the statues of Faith and Hope for the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Siena. The Feast of Herod is mostly in stiacciato (a very low bas-relief), with the foreground figures done in bas-relief, and is one of the first examples of one-point perspective in sculpture.

Donatello also restored antique sculptures for the Palazzo Medici.[6]

Bronze David

Donatello's bronze David, now in the Bargello museum, is his most famous work, and the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity. Conceived fully in the round, independent of any architectural surroundings, and largely representing an allegory of the civic virtues triumphing over brutality and irrationality, it is arguably the first major work of Renaissance sculpture. It was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici for the courtyard of his Palazzo Medici, but its date remains the subject of debate. It is most often dated to the 1440s, but dates as later as the 1460s have support from some scholars. It is not to be confused with his stone David, with clothes, of about 1408–09.

Some have perceived the David as having homoerotic qualities and have argued that this reflected the artist's own orientation.[7] The historian Paul Strathern makes the claim that Donatello made no secret of his homosexuality, and that his behaviour was tolerated by his friends.[8] The main evidence comes from anecdotes by Angelo Poliziano in his "Detti piacevoli", where he writes about Donatello surrounding himself with "handsome assistants" and chasing in search of one that had fled his workshop.[9] This may not be surprising in the context of attitudes prevailing in the 15th- and 16th-century Florentine Republic. However, little detail is known with certainty about his private life, and no mention of his sexuality has been found in the Florentine archives (in terms of denunciations)[10] albeit which during this period are incomplete.[11]

Rome, Prato, and Venice

When Cosimo was exiled from Florence, Donatello went to Rome, remaining until 1433. The two works that testify to his presence in this city, the Tomb of Giovanni Crivelli at Santa Maria in Aracoeli, and the Ciborium at St. Peter's Basilica, bear a strong stamp of classical influence.

Donatello's return to Florence almost coincided with Cosimo's. In May 1434, he signed a contract for the marble pulpit on the facade of Prato cathedral, the last project executed in collaboration with Michelozzo. This work, a passionate, pagan, rhythmically conceived bacchanalian dance of half-nude putti, was the forerunner of the great Cantoria, or singing tribune, at the Duomo in Florence on which Donatello worked intermittently from 1433 to 1440 and was inspired by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests. In 1435, he executed the Annunciation for the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, inspired by 14th-century iconography, and in 1437–1443, he worked in the Old Sacristy of the San Lorenzo in Florence, on two doors and lunettes portraying saints, as well as eight stucco tondos. From 1438 is the wooden statue of St. John the Baptist for Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice.

In Padua

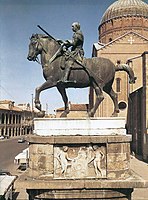

In 1443, Donatello was called to Padua by the heirs of the famous condottiero Erasmo da Narni (better known as the Gattamelata, or "Honey-Cat"), who had died that year. Completed in 1450 and placed in the square facing the Basilica of St. Anthony, his Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata was the first example of such a monument since ancient times. (Other equestrian statues, from the 14th century, had not been executed in bronze and had been placed over tombs rather than erected independently, in a public place.) This work became the prototype for other equestrian monuments executed in Italy and Europe in the following centuries.

For the Basilica of St. Anthony, Donatello created, most famously, the bronze Crucifix of 1444–47 and additional statues for the choir, including a Madonna with Child and six saints, constituting a Holy Conversation, which is no longer visible since the renovation by Camillo Boito in 1895. The Madonna with Child portrays the Child being displayed to the faithful, on a throne flanked by two sphinxes, allegorical figures of knowledge. On the throne's back is a relief of Adam and Eve. During this period—1446–50—Donatello also executed four importantwhy? reliefs with scenes from the life of St. Anthony for the high altar. He remained in Padua until 1453, when he returned to Florence.

Works

| Title | Form | Material | Year | Original location | Current location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crucifix | Statue | Wood, polychromed | 1407–1408 | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce, Cappella Bardi di Vernio |

| Prophet | Statue | Marble | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Porta della Mandorla | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| David (with the head of Goliath) | Statue (originally with sling) | Marble | 1408–1409 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, planned for butress, Palazzo Vecchio (1416) | Florence, Museo nazionale del Bargello |

| John Evangelist | Statue in niche, sitting | Marble | 1408–1415 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, façade | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Joshua | Statue (5.5 mts high) | Terracotta, whitened | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, north tribune | disintegrated |

| Saint Mark | Statue in niche | Marble | 1411–1413 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florenz, Orsanmichele museum |

| St. Louis of Toulouse | Statue in niche | Bronze, gilded (ormolu) | 1411–1415 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Santa Croce (since the 1450s) |

| Prophets | Statues in niche (two of four) | Marble | 1415 and 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| St. George (with Saint George Freeing the Princess) | Statue and niche with predella in relief | Marble | 1416, circa | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (with niche) |

| Marzocco | Statue | Sandstone | 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria Novella, papal apartment | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pazzi Madonna | Relief, low | Marble | 1420, circa | uncertain | Berlin, Bode Museum, Skulpturensammlung |

| San Rossore Reliquary | Bust | Bronze, gilded | 1422–1427 | Florence, Ognissanti | Pisa, Museo nazionale di San Matteo |

| Jeremiah | Statue in niche (third of four) | Marble | 1423, circa | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Zuccone (Prophet Habakkuk) | Statue in niche (last of four) | Marble | 1423–1425 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| The Feast of Herod | Relief | Bronze | 1423–1427 | Siena, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Baptismal font | Siena, Baptistry |

| Madonna of the Clouds | Relief | Bronze | 1425-1435 | Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | |

| Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci | Tomb monument with Statues, reliefs, partly gilded and polychrome | Marble | 1426–1428 | Naples, Sant'Angelo a Nilo | Neapel, Sant'Angelo a Nilo |

| Dovizia (on the Colonna dell'Abbondanza) | Statue on column | Marble (with a working bell) | 1431 | Florence, Piazza della Repubblica | deteriorated and destroyed in a fall in 1721 (replaced with a version by Giovanni Battista Foggini that was replaced by a copy) |

| David (with head of Goliath) | Statue | Bronze, partly gilded | 1430s–1450s (?) | Florence, Casa Vecchia de' Medici | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pulpit, Cantoria | Pulpit with high reliefs | Marble, mosaic, bronze | 1433–1438 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Pulpit, external | Reliefs | Marble | 1434–1438 | Prato, cathedral | Prato, Cathedral Museum |

| Old Sacristy (doors, lunettes, tondi and frieze) | Reliefs, low | Bronze (doors), polychromed stucco | 1434–1443 | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

| Cavalcanti Annunciation | Relief, high, in an aedicula | Pietra serena (Macigno) and terracotta, whitened and gilded | 1435, circa | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Wood, painted partially gilded | 1438 | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari |

| Amor-Attys (Notname) | Statue | Bronze | 1440, circa | Florence | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Penitent Magdalene | Statue | Wood and stucco pigmented and gilded | 1440–1442 (?) | Florence | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Madonna and Child | Relief, low | Terracotta, pigmented | 1445 (1455) | unknown | Paris, Louvre |

| Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata | Statue, equestrian monument | Bronze | 1445–1450 | Padua, Piazza Sant'Antonio | Padua, Piazza Sant'Antonio |

| High altar with Madonna with Child, six statues of Saints and four episodes of the life of St. Anthony | Statues (seven) and 21 reliefs | Bronze (and one stone relief) | 1446, after | Padua, Basilica di Sant'Antonio | Padua, Basilica di Sant'Antonio (reconstruction) |

| Judith and Holofernes | Statue group | Bronze | 1453–1457 | Florence, Palazzo Medici, garden | Florence, Palazzo Vecchio |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Bronze | 1455, circa | Siena, Cathedral | Siena, Dom |

| Virgin and Child with Four Angels or Chellini Madonna | Relief, low, tondo | Bronze, gilded | 1456, before | Florence | London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Pulpits, one with scenes of the Passion, one with post-Passion scenes | Reliefs | Bronze | 1460, after | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

Gallery

-

Saint John the Evangelist (1408-1415), which until 1588 occupied a niche of the old Florence Cathedral façade, now at the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Donatello's David head and shoulders front right

-

Madonna and Child, painted terracotta, c. 1440, Louvre

-

Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata (1445–1450), Padua

-

Statue of St. John the Baptist in the Duomo di Siena, c. 1455

-

Penitent Magdalene, wood, c. 1440-1442, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

-

Il Cristo di Sant'Angelo di Legnaia

2020 discovery

In 2020 art historian Gianluca Amato, as part of his research on wooden crucifixes crafted between the late thirteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century for his doctoral thesis at the University of Naples Federico II, discovered that the crucifix of the church of Sant'Angelo a Legnaia was sculpted by Donatello.

This discovery has been evaluated historically, considering that the work belonged to the Compagnia di Sant'Agostino that was based in the oratory adjacent to the mother church of Sant'Angelo a Legnaia. Silvia Bensì performed restoration work on the crucifix.[12][13][14][15]

In popular culture

Donatello is portrayed by Ben Starr in the 2016 television series Medici: Masters of Florence.[16]

The fictional crimefighter Donatello, one of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, is named after him.

Donatello is portrayed by Rhett McLaughlin in the 2014 Epic Rap Battles of History video Artists versus Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in which he appears working on Gattamelata and is mocked for being less famous than other Renaissance artists. [17]

The Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) built by the Italian Space Agency, was one of three MPLMs operated by NASA to transfer supplies and equipment to and from the International Space Station. The others were named Leonardo and Raffaello.

References

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Rubin, Patricia Lee (January 1995). Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. p. 350. ISBN 9780300049091.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. xi. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. 26, 30, 34. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Horst W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1963, p. ?page needed.

- ^ Hesson, Robert (28 July 2019). "Collections and restoration of antiquities – Ancient Monuments". Northern Architecture. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ H.W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 77–86; Laurie Schneider, "Donatello's Bronze David," The Art Bulletin, 55 (1973) 213–216.

- ^ Paul Strathern, The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, London, 2003

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence[page needed]

- ^ Joachim Poeschke, Donatello and His World. Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, Volume 1, Harry N Abrams, New York 1993, p. ?

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard Press, 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Mugnaini, Olga (6 March 2020). "'Quel crocifisso ligneo è di Donatello', la sensazionale scoperta a Firenze". La Nazione (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Studioso scopre Crocifisso inedito di Donatello". Adnkronos. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Salzano, Marco Pipolo & Guido. "E". QAeditoria.it – QA turismo cultura & arte. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Crocifisso di Donatello nella chiesa di Legnaia, la storia". Isolotto Legnaia Firenze (in Italian). 6 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Medici: Masters of Florence". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ ERB. "Artists vs TMNT. Epic Rap Battles of History". YouTube. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Donatello". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–408.

Further reading

- Avery, Charles, Donatello: An Introduction, New York, 1994.

- Avery, Charles, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Firenze 1991.

- Avery, Charles and McHam, Sarah Blake, "Donatello". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- Bennett, Bonnie A. and Wilkins, David G., Donatello, Oxford 1984.

- Coonin, A. Victor, Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art, Reaktion Books, London, 2019.

- Greenhalgh, Michael, Donatello and His Sources, Holmes & Meier Pub., 1982.

- Hartt, Frederick and Wilkins, David G., History of Italian Renaissance Art (7th ed.), Pearson, 2010.

- Janson, Horst W., The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Leach, Patricia Ann, Images of Political Triumph: Donatello's Iconography of Heroes, Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Olson, Roberta J.M., Italian Renaissance Sculpture, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 978-0500202531

- Randolph, Adrian W.B., Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence. Yale University Press, 2002.

- Vasari, Giorgio, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Firenze 1568, edizione a cura di R. Bettarini e P. Barocchi, Firenze, 1971.

- Wilson, Carolyn C., Renaissance Small Bronze Sculpture and Associated Decorative Arts, 1983, National Gallery of Art (Washington), ISBN 0894680676