Flags and emblems of Majapahit

The Majapahit flag and emblem refers to the royal colors and symbols used to represent the Majapahit empire.[1] However, the nature of how the colors and the symbols were used and represented is still a subject of study and disagreement among historians.[2]

The red-and-white color combination is flown by the Indonesian Navy in the Republic of Indonesia Ship (KRI) as naval jack and pennon, with the name "Lencana Perang" and "Ular-Ular Perang" respectively.[3]

History[edit]

The red and white banner is recorded in the Kudadu inscription dated 1294 AD. In the inscription it is said that the red and white banners were flown by Jayakatwang troops from Daha who were chasing Raden Wijaya's troops.[4] The Red and White Charter is another name for the Kudadu inscription.[5] It was stated that Raden Wijaya was being chased by Jayakatwang's troops carrying the flag, when suddenly "the enemy's banner was seen east of Hanyiruh, the colors were red and white" (hana ta tuṅgulniṁ atru layū-layū katon·vetani hañiru[h], bāṁ lāvan putiḥ varṇnanya). This is found on the 3rd line of Kudadu 4v inscription.[6]

When King Hayam Wuruk made a visit to the whole country of Majapahit, the red and white color was noted to be used as a sign of the entourage. Recorded in Nagarakretagama canto 18 stanza 2–4:[7]

Stanza 2

- nistanyaśankya tang syandana mapawilanan deni cihnanya bheda,

- tekwan lampah nikapanta tulis ika dudu ri sang mantri samantri,

- rakryan sang mantri mukyapatih i majhapahit / sang pranalen kadatwan,

- pinten / kawan[i] śata syandana pulupulutan teki cihnanya neka.

Stanza 3

- sang śri natheng pajang kwehni rathanira padacihnaning handiwaśri,[ii]

- ndan / śri natheng lasem / sök / rathanira matulis / nandaka śweta śobha,

- sang śri natheng daha cihna sadak akusuma[iii] syandanabhratulis mas,

- mukyang śri jiwanendrasakata samasama cihna lobheng lwih sök.

Stanza 4

- ndan sang śri tiktawilwaprabhu sakataniraśankya cihnanya wilwa,

- gringsing lobheng lwih laka pada tinulis ing mas kajangnyan rinenga,

- salwirning pungawamwat / bini haji nuniweh .. śwari śri sudewi,

- sakwehning pekabharyya sakata nika sinang panharpning sapanta.

Translations:[10]

Stanza 2

- Although numberless, yet the carts had means to be counted, namely by their different marks.

- Naturally the tour of those (carts) went in groups; those drawings (on their sides) were not the same from one mantri to another.

- The rakryan (Right Honourable) the honoured mantri-principal, the prime-minister of Majapahit, is the honoured mediator of the Royal Family.

- Even as many as four hundred carts; pupulutan was their mark, in great numbers.

Stanza 3

- The honoured Illustrious Protector of Pajang, the great number of Her wagons alike had the mark of the handiwa (sugar-palm), glorious.

- Then, the Illustrious Protector of Lasem, crowded were Her wagons, with drawings: a white bull, splendid.

- The honoured IIlustrious Protector of Daha had for marks: sadak (betel leaves) with flowers; the carts were glittering with drawings of gold.

- The principal is the IIlustrious Jiwana-monarch, with cars all alike having for mark: lobheng lewih figures, crowded.

Stanza 4

- Then the honoured Illustrious Tikta Wilwa (Majapahit) Prabhu, His cars were numberless, their marks were wilwas (maja / bael fruit).

- Of gringsing, lobheng-lewih, laka, alike drawn in gold, were their kajangs (screens), with ornaments.

- All kinds of punggawas (superior serving-men) conveyed the bini hajis (ladies of the keputren), and also the Mistress the IlIustrious Sudewi.

- All the followers' wives, those cars were open, the vanguard of the whole group.

From the translation, the colors and emblems used by Majapahit can be classified as follows:[11]

| Group | Emblem | Motif | Color | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prime minister Gajah Mada | Pupulutan (Urena lobata) | - | - | |

| Ruler of Pajang | Handiwa—Sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) | - | Dark color | According to Pigeaud, Hayam Wuruk's sister |

| Ruler of Lasem | White bull | - | White | According to Pigeaud, Hayam Wuruk's cousin |

| Ruler of Daha | Betel leaves with flowers | - | Green and gold | According to Pigeaud, Hayam Wuruk's aunt |

| Ruler of Jiwana | - | Lobheng lewih | Red and white | The ruler of Jiwana-Kahuripan according to Pigeaud was the mother of the King |

| King Hayam Wuruk | Maja / bael fruit—Aegle marmelos | Gringsing, lobheng lewih | Black-white, red-white, laka (red), mas (gold) |

Red and white color are used as the colors of the kajang—meaning the side curtains or the semi-cylindrical roof of the carriages, made of palm leaves tacked together or plaited. The red-white combination is considered the most noble.[12]

Lobheng lewih is the name of an ornate motif for a painting, drawing, or textile.[9] This motif is colored red and white, the combination is called gula-kalapa, which is the opposite of pare-anom, namely the green and gold colors, which Daha uses. The combination of red and white is considered the most exalted in Java.[12]

Gringsing is also the name of a decorative motif, especially for weaving and batik. It was probably white and black-colored, spotted, or dotted.[12]

In Nagarakretagama canto 84 stanza 4 also mentioned banners (Old Javanese: dwaja atau dhwaja). The color is not stated, Pigeaud argues that such banners have a symbolic color, with red-white (gula-klapa) be the most sublime combination.[13][14][15]

Sukarno depicted the maritime banner of Majapahit with alternating red and white lines, called it Sang Getih-Getah (The Red-and-White).[16]

State emblem[edit]

The state emblem of Majapahit (rajasa lancana) is mentioned in Nagarakretagama canto 18 stanza 4. It is noted that when King Hayam Wuruk went to Lumajang, the king's chariot had a cihna, which means identification mark.[17] Its symbol is the wilwa (Sanskrit for maja / bael fruit—Aegle marmelos). The round shape of the maja fruit was probably associated with the position of the king and capital of Majapahit as the center of the Majapahit mandala.[12]

Notes[edit]

- ^ H. Kern wrote mawan. According to Pigeaud, pinten is used in connection with numbers so mawan doesn't make sense here. He replaced it with kawan, meaning "four" (from "sekawan", the formal idiom).[8]

- ^ H. Kern wrote diwaśaśri, which Pigeaud thought was not making sense. Pigeaud's emendation is handiwaśri, handiwa is other name for sugar-palm.[8]

- ^ N.J. Krom wrote sadahakusuma, which Pigeaud thought was not making sense. The original reading is probably sadak akusuma, betel leaves with flowers.[9]

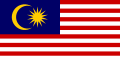

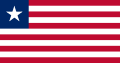

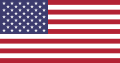

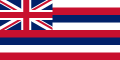

Other flags[edit]

Flags with similar design:

-

Indonesian Navy naval jack

-

Bali Kingdom flag

-

Flag of the British East India Company (1801–1874)

-

Singapore flag with the addition of a crescent moon and five small stars arranged in a pentagon

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Wasitaatmadja 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Budianto, Enggran Eko (2022-01-14). "Salah Kaprah Lambang Kerajaan-Bendera Majapahit dan Buah Maja". detikJatim. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ Moelyono, Setiyo, ed. (29 January 2020). "Tradisi TNI Angkatan Laut: Pewarisan Nilai-Nilai Luhur dalam Membangun Semangat Juang dan Karakter Prajurit Matra Laut" (PDF). Dinas Perawatan Personel Angkatan Laut (in Indonesian). Indonesian Navy. pp. 76–79. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Yamin 1954, p. 90-92, 137-150.

- ^ Windoe, Kandi (2015-05-02). "Melihat Kibar Bendera Merah Putih dan Nusantara Sebelum Indonesia". Archived from the original on 2020-09-14. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ Brandes, J.L.A. (1896). Pararaton (Ken Angrok), of Het Boek der Koningen van Tumapĕl en van Majapahit. Batavia: Albrecht & Co. p. 79.

- ^ Pigeaud 1960a, p. 16.

- ^ a b Pigeaud 1960b, p. 38.

- ^ a b Pigeaud 1960b, p. 39.

- ^ Pigeaud 1960c, p. 23-24.

- ^ Pigeaud 1962, p. 53-58.

- ^ a b c d Pigeaud 1962, p. 58.

- ^ Pigeaud 1960a, p. 65.

- ^ Pigeaud 1960c, p. 100.

- ^ Pigeaud 1962, p. 281.

- ^ Ranoewidjojo, Romo Dony S. (2021). "Bendera Gula Kelapa dan Kontras Bayangan Wayang Kulit Nusantara". Majalah Adiluhung Edisi 28: Wayang, Keris, Batik, dan Kuliner Tradisional. PT Daniasta Perdana. p. 18.

- ^ Muljana 2005, p. 58-59.

Bibliography[edit]

- Muljana, Raden Benedictus Slamet (2005). Al-Fayyadl, Muhammad (ed.). Menuju Puncak Kemegahan: Sejarah Kerajaan Majapahit. Yogyakarta: LKiS Pelangi Aksara.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1960a). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History, Volume I: Javanese Texts in Transcription (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1960b). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History, Volume II: Notes on the Texts and the Translations (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-94-011-8774-9.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1960c). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History, Volume III: Translations (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-94-011-8772-5.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1962). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History, Volume IV: Commentaries and Recapitulations (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-94-017-7133-7.

- Pigeaud, Theodoor Gautier Thomas (1963). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History, Volume V: Glossary, General Index (3rd revised ed.). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-94-011-8778-7.

- Prapanca, Mpu (2018). Isidora (ed.). Kakawin Nagarakertagama: Teks Asli dan Terjemahan. Translated by Saktiani, Damaika; Widya, Kartika; Aminullah, Zakaria Pamuji; Marginingrum, Novi; Septi, Neda (2nd revised ed.). Yogyakarta: Narasi. ISBN 978-979-168-553-5.

- Yamin, Mohammad (1954). 600 Tahun Sang Merah-Putih, jaitu Uraian Tentang Hasil-Penjelidikan Sedjarah dan Arti jang dikandung Sang Merah-Putih Sebagai Warna-Kebangsaan. Penerbit Siguntang.

- Wasitaatmadja, Fokky Fuad (2018). Spiritualisme Pancasila. Prenada Media. ISBN 9786024222673.