Gender in public administration

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2015) |

Gender has historically played an important role in public administration. Gender perception and other factors influence the ways in which people think about public administration and bureaucracy. In today's society, public administration remains widely segregated in regard to gender, though it has become commonplace to advocate for greater numbers of equality and non-discrimination policies.

Overview[edit]

During the early years of public administration, textbooks and curriculum largely overlooked minorities and dismissed contributions that reflected women's experience. The later 1900s brought heightened sensitivity of these issues to the forefront, with shifts in public opinion producing the Civil Rights Act, equal opportunity initiatives, and job protection laws. This shift caused public administration to more readily acknowledge the views and voices of others, to finally recognize those besides the "elite" landowners who crafted the U.S. Constitution, and from men of the early 1900s who are credited with establishing public administration as an academic discipline.

In 1864 the U.S. Government declared that when women were employed by the government, they should be paid one half of the salary that a man would be paid to perform exactly the same job. Though equality in this aspect has improved, it still isn't truly equal. (Equal Pay Act of 1963 helped to change this). These cultural holdovers from early eras have influenced the current inequity in pay that still persists today - women currently earn 77.8 cents for every dollar that a man earns.[1]

According to Domonic A. Bearfield of Texas A & M University, "this is particularly true for female federal employees. According to Hsieh and Win-slow (2006), although women have made gains in overall representation, inequality exists among women of different racial and ethnic groups."[2]

History of patrimony in public administration[edit]

Gender norms and the shaping of public administration[edit]

When examining the role of gender in public administration, there are frequently two competing schools of thought: the "feminine" approach centers on social justice issues, while the "masculine" approach emphasizes efficiency and impartiality. These methods were employed harmoniously prior to World War I, with men and women cooperating to "emphasize the principles of classical pragmatism [and focus] on the efficient execution of policy but also on societal cooperation and the strengthening of public knowledge." After the outbreak of the war however, a shift in American public administration occurred. As the public administration system became more reliant on male-dominated organizations such as the Social Science Research Council's Advisory Committee of Public Administration, the system became unsurprisingly more attached to the efficient/objective approach. This much can be seen by the number of philanthropies (many of whom were affiliated with the Rockefeller Family) that began aggressively funding "programs that clearly distinguished between 'scientific research' and the advocacy work" of other organizations.

In addition to the increased reliance on masculine principles, American society's approach to social science began to change and thus influenced public admin. For example, in the late 1890s economists altered the way they studied by focusing less on general trends and more on statistics and hard facts. Sociology, on the other hand, remained focused "on a specialized knowledge based on the value-neutral pursuit of abstract generalizations about human relations" and continued to promote social justice. This dichotomy is largely responsible for the relegation of women to "more congenial specialties such as social work" while men remained leaders in finance and other scientifically driven organizations.[3]

Human capital theory[edit]

People who ascribe themselves to human capital theory have a different explanation of the differing representations of men and women in public administration and workplaces in general. Where some scholars have argued that men and women's roles in government come from a historic separation based on the opposition of "masculine" and "feminine" thought, others have argued that women's decreased role comes from their inferior investment in their personal human capital. In other words, according to these theorists, men reap benefits in society because they are more inclined to pursue greater educations, attain better jobs, and have more work experience. This theory has been largely contested because of the inability of women to secure the same jobs as men with equal qualifications.[4]

The sociopsychological theory[edit]

Following the rise of human capital theory, and in response to many of its criticisms, researchers and sociologists developed the sociopsychological theory. This theory, like human capital theory before it, attributes a great deal of emphasis on the differing qualifications between men and women. What this theory does differently however, is give attention to the sociological constructs that inhibit women's inability to acquire equal qualifications. For example, these theorists argue that where men are typically attributed with social characteristics such as, "aggressiveness, ambition, and self-confidence," women have been deemed "affectionate, kind, sensitive, and soft-spoken" and are therefore like to be regarded by an employer as inferior to a man with the same qualifications. Sociopsychological theorists go on to argue that because of these differences, it is difficult for a woman to enter a profession heavily dominated by men because they are likely to be viewed as incompetent or less competent than their male counterparts. It has been argued that this fear of incompetency has led women to embrace more masculine characteristics at the expense of femininity.

In addition to predictions about the effects of personality traits on the role of women in the workforce, sociopsychological theorists argue that women's representation is largely due to the role of sociological stereotypes and stigmas about the place of women in society. Because it is so widely held (in patrimonial societies) that women are responsible for domestic duties and child-rearing, it has been more difficult for them to advance professionally. Using this information, these theorists have said that the underlying ideas of domestic roles have been so pervasive that they have become integrated into the very institutions of government and business and are often indiscernible. For this reason, the American government has taken action to litigate protection of women in government and workplaces under a variety of Equal Employment Opportunity laws and anti-discrimination policies. Private enterprises have taken measures to limit discrimination by means of training programs, merit hiring, and other policies.[4]

Benefits of gender diversity in public administration[edit]

Gender and diversity are necessary themes in public administration. They remind the field to embrace otherness and to comprehend the effect it has on policies, programs, and outcomes. In recent decades attention to the difference that differentness makes has spurred appreciation for divergent perspectives on, and interpretations of, public service. This is imperative if the discipline is to strive for the normative ideal of democratic governance.[5]

Public administration was first established as a matter of technical implementation where the values of efficiency and effectiveness were paramount. This upside down priority meant that the principles of social equity, protection of minority rights, and equal opportunity, took a back seat to administrative "science".[6] The goal of true integration of women into the workforce is to achieve a "depolarized workplace where the worth of both women and men is appreciated. Without women having to behave like men, their views, perspectives, and skills strengthen the milieu. Just as Mrs. T. J. Bowlker observed so many years ago, gender makes a substantive difference in policy preferences, public initiatives, and stylistic nuances. Women’s contributions complement and enrich the canon, which otherwise presents a skewed representation of the field that overlooks the work of over half the population. Representative bureaucracies can promote democracy in various ways. As a number of scholars have pointed out, representation makes bureaucracies more responsive to the body politic, and can also increase government accountability."[5]

Marginalized gender identities in public administration[edit]

- Women, trans and non-binary folks, etc.

There has been a striking increase in the proportion of MPA students and public administration faculty who are women, perhaps a result of the increase in both supply and demand for gender-related scholarship, or, alternatively, due to the increase in female public administrators. Yet many of the systems that persist in the workplace were built for people who do not get pregnant, who have no need for nursing rooms at the office, no need for maternity leave or early afternoon hours in order to pick children up after school, and have no need for eldercare and childcare responsibilities.[5]

Statistics of marginalized demographics in public administration[edit]

- History of marginalized presence in public administration—Currently, gender, religion, sexuality, representative bureaucracy, and ethnicity, are on the rise. Writings on sexuality are on the increase as more articles appear on the subject of same sex marriage, workplace benefits, and issues surrounding transgender nondiscrimination policy.[5]

International case studies: marginalized gender identities in public administration[edit]

Spanish municipalities[edit]

Upon investigating the gender make-up of 155 Spanish municipalities, researchers discovered that most departments in public administration favored a primarily male population. Of the areas examined, fourteen were identified as having a gender differential of at least 10%, with six having a differential of greater than 50%. These six areas included sports (+ 50.4%), urban planning, planning, etc. (+ 54.6%), transport and mobility (+ 55.2%), citizen safety, emergencies and traffic (+ 57%), works (+ 62), and agriculture, livestock and fisheries (+ 77.8). It is important to note however, that while men dominated more fields than women did, women held an advantage in six areas: women and equality (+ 86.4%), immigration, solidarity, and cooperation (60.6%), social services (+ 28.4), consumption (+ 20%), tourism (+ 11.4%), and education, culture, etc. (+ 10%). In addition to these horizontal divisions, researchers were able to identify vertical divisions in government. In areas where equally existed, it was not uncommon for men to dominate the upper-level positions of a system, with more men occupying mayoral or similar positions while women were found most often to be councilwomen. For the researchers in the study, these statistics painted an interesting picture. Despite the existence of neutral territory (commerce and local markets, citizen participation/attention, employment and training, and internal regime and personnel), certain areas of government were found to be heavily gendered in correlation with existing gender stereotypes with men domination economics and finance and women remaining in areas that have more to deal with social justice. This analysis was then used to conclude that even as women are becoming involved and employed in politics on a much larger scale than in years prior, women remain confined to areas that have been deemed feminine in a predominantly masculine, male-driven system.[7]

Challenges for marginalized gender identities in public admin[edit]

- Social/cultural barriers

- Economic barriers

- National and global scale of barriers

Policies for increased gender representation in public administration[edit]

Policies that are currently active in the United States that aim to increase minority representation in public offices, places and of commerce have become more prevalent in the current political atmosphere.

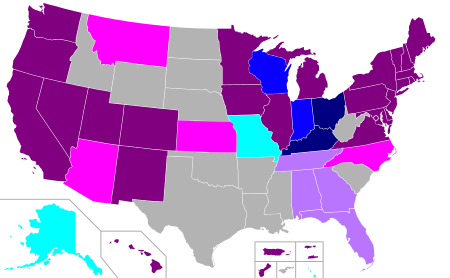

| State Non-Discrimination Policies | Employment Non-Discrimination Act (pending):

Sexual orientation and gender identity: all employment Sexual orientation with anti–employment discrimination ordinance and gender identity solely in public employment Sexual orientation: all employment Sexual orientation and gender identity: state employment Sexual orientation: state employment No state-level protection for LGBT employees |

| Federal Non-Discrimination Policies | Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

|

| Equal Rights Ordinances | Houston Equal Rights Ordinance (HERO):

|

- Movements (i.e. grassroots movements) for more representation policies

Notable figures of marginalized identities in public administration[edit]

Mary Anderson[edit]

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, a movement involving the advocacy of social justice feminism began in the United States under Florence Kelley. It was during this time that many women entered the public sphere as they called for greater women's labor legislation and equality. One of these women, Mary Anderson, achieved great report in public administration through her continued efforts to create and encourage equality in government and in bureaucracy.[citation needed]

Though she immigrated to the United States from Sweden in the mid-1880s, Mary Anderson established a reputation amongst Samuel Gompers and other famous members of the labor movement by the 1910s. Anderson's role in the movement involved the drafting of an important management-labor agreement following a prominent garment worker's strike in 1911. Propelling herself forward from this success amongst labor advocates, Anderson was able to create an "extensive lobbying campaign" to include a women's division in the United States Department of Labor. Despite being unsuccessful in her lobbying endeavors, Anderson's notability granted her the position of head of the Women's Bureau when it was established as a permanent organization following the passage of the 20th amendment in 1920.[3]

Susan Stanton[edit]

Susan Ashley Stanton is a transgender woman and active city manager of Greenfield, California. Stanton made the decision to transition while she was city manager of Largo, Florida. A month after her announcement, Stanton was fired from her position and forced to find work elsewhere. The board that decided to fire her claimed that the vote for Stanton's termination was not related to her announcement, but rather that they did not trust her ability to still manage the city. Stanton had served the city of Largo for 17 years, 14 of them as city manager. For two years Stanton was without a job, until she secured a position as city manager of Lake Worth, Florida, in 2009. Stanton left Lake Worth for Greenfield, California, where she is the current[when?] city manager.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ "United States Census Bureau." 2007 Data Release – Data & Documentation – American Community Survey – U.S. Census Bureau. N.p., n.d. Web. April 22, 2015.

- ^ Bearfield, Domonic (2009). "Equity at the Intersection: Public Administration and the Study of Gender". Public Administration Review. 69 (3): 383–386. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.01985.x. ISSN 0033-3352.

- ^ a b McGuire, John Thomas (2012). "Gender And The Personal Shaping Of Public Administration In The United States: Mary Anderson And The Women's Bureau, 1920-1930". Public Administration Review. 72 (2): 265–271. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02502.x.

- ^ a b Caceres-Rodriguez, Rick (2013). "The Glass Ceiling Revisited: Moving Beyond Discrimination In The Study Of Gender In Public Organizations". Administration & Society. 45 (6): 674–709. doi:10.1177/0095399711429104. S2CID 147098514.

- ^ a b c d Guy, Mary E.; Schumacher, Kristin (2009). "Gender and Diversity in Public Administration" (PDF). University of Colorado Denver. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Critzer, J. W.; Rai, K. B. (1998). "Blacks and women in public higher education: Political and socioeconomic factors underlying diversity at the state level". Women & Politics. 19 (1): 19–38. doi:10.1300/j014v19n01_02.

- ^ Batista Medina, José Antonio (2015). "Public Administrations As Gendered Organizations. The Case Of Spanish Municipalities". Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociologicas. 149: 3–29.

- ^ "Employment Non-Discrimination Act". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Laws Enforced by the EEOC". US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. EEOC. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Morris, Mike. "Council Passes Equal Rights Ordinance" Houston Chronicle. May 28, 2014. Web. April 22, 2015

Further reading[edit]

- Bayes, J. H. (1991). "Women in public administration in the United States". Women & Politics. 11 (4): 85–109. doi:10.1080/1554477x.1991.9970625. ProQuest 213891805.

- Bayes, J. H. (1991). "Women and public administration: A comparative perspective- conclusion". Women & Politics. 11 (4): 111–131. doi:10.1080/1554477x.1991.9970626. ProQuest 213901740.

- Harris, J. W. (1994). "Introductory public administration textbooks: Integrating scholarship on women". Women & Politics. 14 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1300/j014v14n01_04. ProQuest 213902164.

- Stivers, C (1990). "Toward a feminist perspective in public administration theory". Women & Politics. 10 (4): 49–65. doi:10.1080/1554477x.1990.9970587. ProQuest 213892261.

- Hinojosa, Magda; Sahir-Rosenfield, Sarah (2014). "Does Female Incumbency Reduce Gender Bias in Elections? Evidence from Chile". Political Research Quarterly. 67 (4): 4. doi:10.1177/1065912914550044. S2CID 153365228.

- Black, Jerome H.; Erickson, Lynda (2003). "Women Candidates and Voter Bias: Do Women Politicians Need to Be Better?". Electoral Studies. 22: 81–100. doi:10.1016/s0261-3794(01)00028-2.

- Carpinella, Colleen; Johnson, Kerri (2013). "Politics of the Face: The Role of Sex-Typicality In Trait Assessments of Politicians". Social Cognition. 31 (6): 6. doi:10.1521/soco.2013.31.6.770.

- Johns, R.; Shepard, M. (2007). "Gender, candidate image and electoral preference". British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 9 (3): 434–460. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856x.2006.00263.x. S2CID 144866803.

- Lenz, G. S.; Lawson, C. (2011). "Looking the part: Television leads less informed citizens to vote based on candidates' appearance" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3): 574–589. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00511.x. hdl:1721.1/96161.

- Stivers, Camilla. Gender Images In Public Administration : Legitimacy And The Administrative State / Camilla Stivers. n.p.: Thousand Oaks : Sage Publications, [2002], 2002. Texas State - Alkek Library's Catalog. Web. March 8, 2015.

- Park, Sanghee (2013). "Does Gender Matter? The Effect Of Gender Representation Of Public Bureaucracy On Governmental Performance". American Review of Public Administration. 43 (2): 221–242. doi:10.1177/0275074012439933. S2CID 154936915.

- Hutchinson, Janet R.; Mann, Hollie S. (2006). "Gender Anarchy And The Future Of Feminisms In Public Administration". Administrative Theory & Praxis. 28 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1080/10841806.2006.11029536. S2CID 147421551.

- Riccucci, Norma M.; Van Ryzin, Gregg G.; Lavena, Cecilia F. (2014). "Representative Bureaucracy in Policing: Does It Increase Perceived Legitimacy?". J Public Adm Res Theory. 24 (3): 537–551. doi:10.1093/jopart/muu006.