Great Mosque of Kairouan

| Great Mosque of Kairouan | |

|---|---|

Late afternoon panorama of the mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Kairouan, Tunisia |

| Architecture | |

| Groundbreaking | 670 |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

The Great Mosque of Kairouan (Arabic: جامع القيروان الأكبر), also known as the Mosque of Uqba (جامع عقبة بن نافع), is a mosque situated in the UNESCO World Heritage town of Kairouan, Tunisia and is one of the most impressive and largest Islamic monuments in North Africa.[1]

Established by the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi in the year 50 AH (670AD/CE) at the founding of the city of Kairouan, the mosque occupies an area of over 9,000 square metres (97,000 sq ft). It is one of the oldest places of worship in the Islamic world, and is a model for all later mosques in the Maghreb.[2] Its perimeter, of about 405 metres (1,329 ft), contains a hypostyle prayer hall, a marble-paved courtyard and a square minaret. In addition to its spiritual prestige,[3] the Mosque of Uqba is one of the masterpieces of Islamic architecture,[4][5][6] notable among other things for the first Islamic use of the horseshoe arch.

Extensive works under the Aghlabids two centuries later (9th Cent.AD/CE) gave the mosque its present aspect.[7] The fame of the Mosque of Uqba and of the other holy sites at Kairouan helped the city to develop and expand. The university, consisting of scholars who taught in the mosque, was a centre of education both in Islamic thought and in the secular sciences.[8] Its role at the time can be compared to that of the University of Paris in the Middle Ages.[9] With the decline of the city from the mid-11th century, the centre of intellectual thought moved to the University of Ez-Zitouna in Tunis.[10]

Location and general aspect

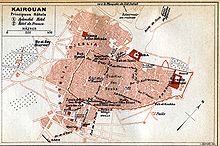

Located in the north-east of the medina of Kairouan, the mosque is in the intramural district of Houmat al-Jami (literally "area of the Great Mosque").[11] This location corresponded originally to the heart of the urban fabric of the city founded by Uqba ibn Nafi. However given the natural lay of the land crossed by several tributaries of the wadis, the urban development of the city spread southwards. Human factors including Hilalian's invasions in 449 AH (1057 AD) led to the decline of the city and halted development. For all these reasons, the mosque which once occupied the center of the medina when first built in 670 is now on the easternmost quarter abutting the city walls.

The building is a vast slightly irregular quadrilateral covering some 9,000 m2. It is longer (127.60 metres) on the east side than the west (125.20 metres), and shorter on the north side (72.70 metres) than the south (78 metres). The main minaret is centered on the north.

From the outside, the Great Mosque of Kairouan is a fortress-like building with its 1.90 metres thick massive ocher walls, a composite of well-worked stones with intervening courses of rubble stone and baked bricks.[12] The corner towers measuring 4.25 metres on each side are buttressed with solid projecting supports. Structurally given the soft grounds subject to compaction, the buttressed towers added stability to the entire mosque.[13] Despite the austere façades, the rhythmic patterns of buttresses and towering porches, some surmounted by cupolas, give the sanctuary a sense of striking sober grandeur.[13][14]

History

Evolution

At the foundation of Kairouan in 670, the Arab general and conqueror Uqba ibn Nafi (himself the founder of the city) chose the site of his mosque in the center of the city, near the headquarters of the governor. Around 690, shortly after its construction, the mosque was destroyed[15] during the occupation of Kairouan by the Berbers, originally conducted by Kusaila. It was rebuilt by the Ghassanid general Hasan ibn al-Nu'man in 703.[16] With the gradual increase of the population of Kairouan and the consequent increase in the number of faithful, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, Umayyad Caliph in Damascus, charged his governor Bishr ibn Safwan to carry out development work in the city, which included the renovation and expansion of the mosque around the years 724–728.[17] During this expansion, he pulled down the mosque and rebuilt it with the exception of the mihrab. It was under his auspices that the construction of the minaret began.[18] In 774, a new reconstruction accompanied by modifications and embellishments[19] took place under the direction of the Abbasid governor Yazid ibn Hatim.[20]

Under the rule of the Aghlabid dynasty, Kairouan was at its apogee, and the mosque profited from this period of stability and prosperity. In 836, Emir Ziyadat Allah I reconstructed the mosque once more:[21] this is when the building acquired, at least in its entirety, its current appearance.[22][23] At the same time, the mihrab's ribbed dome was raised on squinches.[24] Around 862–863, Emir Abu Ibrahim enlarged the oratory, with three bays to the north, and added the cupola over the arched portico which precedes the prayer hall.[25] In 875 Emir Ibrahim II built another three bays, thereby reducing the size of the courtyard which was further limited on the three other sides by the addition of double galleries.[26]

The current state of the mosque can be traced back to the Aghlabid period—no element is earlier than the ninth century besides the mihrab—except for some partial restorations and a few later additions made in 1025 during the Zirid period,[27] 1248 and 1293–1294 under the reign of the Hafsids,[28] 1618 at the time of Muradid beys,[29] and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In 1967, major restoration works, executed during five years and conducted under the direction of the National Institute of Archeology and Art, were achieved throughout the monument, and were ended with an official reopening of the mosque during the celebration of the Mawlid of 1972.[30]

Host stories

Several centuries after its founding, the Great Mosque of Kairouan is the subject of numerous descriptions by Arab historians and geographers in the Middle Ages. The stories concern mainly the different phases of construction and expansion of the sanctuary, and the successive contributions of many princes to the interior decoration (mihrab, minbar, ceilings, etc.). Among the authors who have written on the subject and whose stories have survived[22] are Al-Bakri (Andalusian geographer and historian who died in 1094 and who devoted a sufficiently detailed account of the history of the mosque in his book Description of Septentrional Africa), Al-Nuwayri (historian who died in Egypt, 1332) and Ibn Nagi (scholar and historian of Kairouan who died around 1435).

On additions and embellishments made to the building by the Aghlabid emir Abu Ibrahim, Ibn Nagi gives the following account:

« He built in the mosque of Kairouan the cupola that rises over the entrance to the central nave, together with the two colonnades which flank it from both sides, and the galleries were paved by him. He then made the mihrab. »[22]

Among the Western travelers, poets and writers who visited Kairouan, some of them leave impressions and testimonies sometimes tinged with emotion or admiration on the mosque. From the eighteenth century, the French doctor and naturalist John Andrew Peyssonnel, conducting a study trip to 1724, during the reign of sovereign Al-Husayn Bey I, underlines the reputation of the mosque as a deemed centre of religious and secular studies:

« The Great Mosque is dedicated to Uqba, where there is a famous college where we will study the remotest corners of this kingdom : are taught reading and writing of Arabic grammar, laws and religion. There are large rents for the maintenance of teachers. »[31]

At the same time, the doctor and Anglican priest Thomas Shaw (1692–1751),[32] touring the Tunis Regency and passes through Kairouan in 1727, described the mosque as that: "which is considered the most beautiful and the most sacred of Berberian territories", evoking for example: "an almost unbelievable number of granite columns".[33]

At the end of the nineteenth century, the French writer Guy de Maupassant expresses in his book La vie errante (The Wandering Life), his fascination with the majestic architecture of the Great Mosque of Kairouan as well as the effect created by countless columns: "The unique harmony of this temple consists in the proportion and the number of these slender shafts upholding the building, filling, peopling, and making it what it is, create its grace and greatness. Their colorful multitude gives the eye the impression of unlimited".[34] Early in the twentieth century, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke describes his admiration for the impressive minaret:

« Is there a more beautiful than this still preserved old tower, the minaret, in Islamic architecture? In the history of Art, its three-storey minaret is considered such a masterpiece and a model among the most prestigious monuments of Muslim architecture. »[35]

Architecture and decoration

Exterior

Enclosure

Today, the enclosure of the Great Mosque of Kairouan is pierced by nine gates (six opening on the courtyard, two opening on the prayer hall and a ninth allows access to the maqsura) some of them, such as Bab Al-Ma (gate of water) located on the western façade, are preceded by salient porches flanked by buttresses and surmounted by ribbed domes based on square tholobate which are porting squinches with three vaults.[12][36] However, Arab geographers and historians of the Middle Ages Al-Muqaddasi and Al-Bakri reported the existence, around the tenth and eleventh centuries, of about ten gates named differently from today. This reflects the fact that, unlike the rest of the mosque, the enclosure has undergone significant changes to ensure the stability of the building (adding many buttresses). Thus, some entries have been sealed, while others were kept.[12]

During the thirteenth century, new gates were opened, the most remarkable, Bab Lalla Rihana dated from 1293, is located on the eastern wall of the enclosure.[12] The monumental entrance, work of the Hafsid sovereign Abu Hafs `Umar ibn Yahya (reign from 1284 to 1295),[37] is entered in a salient square, flanked by ancient columns supporting horseshoe arches and covered by a dome on squinches.[12] The front façade of the porch has a large horseshoe arch relied on two marble columns and surmounted by a frieze adorned with a blind arcade, all crowned by serrated merlons (in a sawtooth arrangement).[38] Despite its construction at the end of the thirteenth century, Bab Lalla Rihana blends well with all of the building mainly dating from the ninth century.[38]

- Enclosure and gates of the Mosque of Uqba

-

Wall and porches on the west facade (south side)

-

Close view of one of the entrances of the west facade

-

View of the middle of the southern facade

-

Gate of Bab Lalla Rihana (late thirteenth century)

-

Close view of the lower part of Bab Lalla Rihana

-

Blind arcade decorating the upper part of Bab Lalla Rihana

Courtyard

The courtyard is a vast trapezoidal area whose interior dimensions are approximately 67 by 52 metres.[39][40] It is surrounded on all its four sides by a portico with double rows of arches, opened by slightly horseshoe arches supported by columns in various marbles, in granite or in porphyry, reused from Roman, Early Christian or Byzantine monuments particularly from Carthage.[14] Access to the courtyard by six side entrances dating from the ninth and thirteenth centuries.

The portico on the south side of the courtyard, near the prayer hall, includes in its middle a large dressed stone pointed horseshoe arch which rests on ancient columns of white veined marble with Corinthian capitals. This porch of seven metres high is topped with a square base upon which rests a semi-spherical ribbed dome; the latter is ribbed with sharp-edged ribs. The intermediary area, the dodecagonal drum of the dome, is pierced by sixteen small rectangular windows set into rounded niches.[41] The great central arch of the south portico, is flanked on each side by six rhythmically arranged horseshoe arches, which fall on twin columns backed by pillars.[42] Overall, the proportions and general layout of the façade of the south portico, with its thirteen arches of which that in the middle constitutes a sort of triumphal arch crowned with a cupola, form an ensemble with "a powerful air of majesty", according to the French historian and sociologist Paul Sebag (1919–2004).[43]

- Courtyard area and porticoes

-

View of the courtyard on the side of the prayer hall facade

-

Porch topped with a ribbed dome rising in the middle of the south portico of the courtyard

-

Courtyard seen from one of the arched galleries

-

Portico located on the eastern side of the courtyard

-

Interior view of the eastern portico of the courtyard

-

Interior view of the western portico of the courtyard

Details of the courtyard

The combination formed by the courtyard and the galleries that surround it covers an immense area whose dimensions are about 90 metres long and 72 metres in width.[44] The northern part of the courtyard is paved with flagstones while the rest of the floor is almost entirely composed of white marble slabs. Near its centre is an horizontal sundial, bearing an inscription in naskhi engraved on the marble dating from 1258 AH (which corresponds to the year 1843) and which is accessed by a little staircase; it determines the time of prayers. The rainwater collector or impluvium, probably the work of the Muradid Bey Mohamed Bey al-Mouradi (1686–1696), is an ingenious system that ensures the capture (with the slightly sloping surface of the courtyard) then filtering stormwater at a central basin furnished with horseshoe arches sculpted in white marble.[44] Freed from its impurities, the water flows into an underground cistern supported by seven-metre-high pillars. In the courtyard there are also several water wells some of which are placed side by side. Their edges, obtained from the lower parts of ancient cored columns,[45] support the string grooves back the buckets.

- Details of the courtyard

-

The horizontal sundial located in the courtyard

-

One of the courtyard's capitals surmounted by a small vertical sundial

-

Detail of arches and columns of the north portico of the courtyard

-

View of the impluvium which collects the rainwater and feeds the underground cistern

-

Focus on the rainwater collecting basin

-

Focus on one well of the courtyard

Minaret

The minaret, which occupies the centre of the northern façade of the complex's enclosure, is 31.5 metres tall and is seated on a square base of 10.7 metres on each side.[46] It is located inside the enclosure and does not have direct access from the outside. It consists of three tapering levels, the last of which is topped with a small ribbed dome that was most probably built later than the rest of the tower.[47] The first and second stories are surmounted by rounded merlons which are pierced by arrowslits. The minaret served as a watchtower, as well as to call the faithful to prayer.[47]

The door giving access to the minaret is framed by a lintel and jambs made of recycled carved friezes of antique origin.[48] There are stone blocks from the Roman period that bear Latin inscriptions. Their use probably dates to the work done under the Umayyad governor Bishr ibn Safwan in about 725 AD, and they have been reused at the base of the tower.[48] The greater part of the minaret dates from the time of the Aghlabid princes in the ninth century. It consists of regular layers of carefully cut rubble stone, thus giving the work a stylistically admirable homogeneity and unity.[49]

The interior includes a staircase of 129 steps, surmounted by a barrel vault, which gives access to the terraces and the first tier of the minaret. The courtyard façade (or south façade) of the tower is pierced with windows that provide light and ventilation,[50] while the other three façades—facing north, east and west—are pierced with small openings in the form of arrowslits.[46] The minaret, in its present aspect, dates largely from the early ninth century, about 836 AD. It is the oldest minaret in the Muslim world,[51][52] and it is also the world's oldest minaret still standing.[53]

Due to its age and its architectural features, the minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan is the prototype for all the minarets of the western Islamic world: it served as a model in both North Africa and in Andalusia.[54] Despite its massive form and austere decoration, it nevertheless presents a harmonious structure and a majestic appearance.[50][55]

- Minaret

-

Minaret seen from the courtyard

-

Door of the minaret

-

View of the second and third storeys of the minaret

-

Close view of one of the Roman stones (with Latin inscriptions) reused at the base of the minaret

-

Wall and windows of the south facade of the minaret

-

Minaret seen at night

Domes

The Mosque has several domes, the largest being over the mihrab and the entrance to the prayer hall from the courtyard. The dome of the mihrab is based on an octagonal drum with slightly concave sides, raised on a square base, decorated on each of its three southern, eastern and western faces with five flat-bottomed niches surmounted by five semi-circular arches,[24][56] the niche in the middle is cut by a lobed oculus enrolled in a circular frame. This dome, whose construction goes back to the first half of the ninth century (towards 836), is one of the oldest and most remarkable domes in the western Islamic world.[57]

Interior

Prayer hall

The prayer hall is located on the southern side of the courtyard; and is accessed by 17 carved wooden doors. A portico with double row of arches precede the spacious prayer hall, which takes the shape of a rectangle of 70.6 metres in width and 37.5 metres' depth.[58]

The hypostyle hall is divided into 17 aisles of eight bays, the central nave is wider, as well as the bay along the wall of the qibla.[59] They cross with right angle in front of the mihrab, this device, named "T shape", which is also found in two Iraqi mosques in Samarra (around 847) has been adopted in many North African and Andalusian mosques where it became a feature.[60]

The central nave, a sort of triumphal alley which leads to the mihrab,[61] is significantly higher and wider than the other sixteen aisles of the prayer hall. It is bordered on each side of a double row of arches rested on twin columns and surmounted by a carved plaster decoration consisting of floral and geometric patterns.[62]

Enlightened by impressive chandeliers which are applied in countless small glass lamps,[63] the nave opens into the south portico of the courtyard by a monumental delicately carved wooden door, made in 1828 under the reign of the Husainids.[64] This sumptuous door, which has four leaves richly carved with geometric motifs embossed on the bottom of foliages and interlacing stars, is decorated at the typanum by a stylised vase from which emerge winding stems and leaves.[65] The other doors of the prayer hall, some of which date from the time of the Hafsids,[66] are distinguished by their decoration which consists essentially of geometric patterns (hexagonal, octagonal, rectangular patterns, etc.).[58]

- Prayer hall

-

View of the gallery which precedes the prayer hall

-

One of the seventeen carved-wood doors of the prayer hall

-

Close view of the upper part of the main door of the prayer hall

-

View of the central nave of the prayer hall

-

View of two of the secondary naves of the prayer hall

-

View of the mihrab located in the middle of the qibla wall of the prayer hall

Columns and ceiling

In the prayer hall, the 414 columns of marble, granite or porphyry[67] (among more than 500 columns in the whole mosque),[68] taken from ancient sites in the country such as Sbeitla, Carthage, Hadrumetum and Chemtou,[58] support the horseshoe arches. A legend says they could not count them without going blind.[69] The capitals resting on the column shafts offer a wide variety of shapes and styles (Corinthian, Ionic, Composite, etc.).[58] Some capitals were carved for the mosque, but others come from Roman or Byzantine buildings (dating from the second to sixth century) and were reused. According to the German archaeologist Christian Ewert, the special arrangement of reused columns and capitals surrounding the mihrab obeys to a well-defined program and would draw symbolically the plan of the Dome of the Rock.[70] The shafts of the columns are carved in marble of different colors and different backgrounds. Those in white marble come from Italy,[58] some shafts located in the area of the mihrab are in red porphyry imported from Egypt,[71] while those made of greenish or pink marble are from quarries of Chemtou, in the north-west of current Tunisia.[58] Although the shafts are of varying heights, the columns are ingeniously arranged to support fallen arches harmoniously. The height difference is compensated by the development of variable bases, capitals and crossbeams; a number of these crossbeams are in cedar wood.[58] The wooden rods, which usually sink to the base of the transom, connect the columns together and maintain the spacing of the arches, thus enhancing the stability of all structures which support the ceiling of the prayer hall.[72]

The covering of the prayer hall consists of painted ceilings decorated with vegetal motifs and two domes: one raised at the beginning of the central nave and the other in front of the mihrab. The latter, which its hemispherical cap is cut by 24 concave grooves radiating around the top,[73] is based on ridged horns shaped shell and a drum pierced by eight circular windows which are inserted between sixteen niches grouped by two.[56][74] The niches are covered with carved stone panels, finely adorned with characteristic geometric, vegetal and floral patterns of the Aghlabid decorative repertoire: shells, cusped arches, rosettes, vine-leaf, etc.[56] From the outside, the dome of the mihrab is based on an octagonal drum with slightly concave sides, raised on a square base, decorated on each of its three southern, Easter and western faces with five flat-bottomed niches surmounted by five semi-circular arches,[24][56] the niche in the middle is cut by a lobed oculus enrolled in a circular frame.

The painted ceilings are a unique ensemble of planks, beams and brackets, illustrating almost thousand years of the history of painting on wood in Tunisia. Wooden brackets offer a wide variety of style and decor in the shape of a crow or a grasshopper with wings or fixed, they are characterised by a setting that combines floral painted or carved, with grooves. The oldest boards date back to the Aghlabid period (ninth century) and are decorated with scrolls and rosettes on a red background consists of squares with concave sides in which are inscribed four-petaled flowers in green and blue, and those performed by the Zirid dynasty (eleventh century) are characterised by inscriptions in black kufic writing with gold rim and the uprights of the letters end with lobed florets, all on a brown background adorned with simple floral patterns.

The boards painted under the Hafsid period (during the thirteenth century) offers a floral decor consists of white and blue arches entwined with lobed green. The latest, dated the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (mostly dating from the time of the Muradid Beys), are distinguished by an epigraphic decoration consists of long black and red texts on olive green background to those painted from 1618 to 1619, under the reign of Murad I Bey (1613–1631), while those back to the eighteenth century have inscriptions in white naskhi script on an orange background.[75]

Mihrab and minbar

The mihrab, which indicates the Qibla (direction of Mecca), in front of which stands the imam during the prayer, is located in the middle of the southern wall of the prayer hall. It is formed by an oven-shaped niche framed by two marble columns and topped by a painted wooden half-cupola. The niche of the mihrab is two metres long, 4.5 metres high and 1.6 metres deep.[76]

The mosque's mihrab, whose decor is a remarkable witness of Muslim art in the early centuries of Islam, is distinguished by its harmonious composition and the quality of its ornaments. Considered as the oldest example of concave mihrab, it dates in its present state to 862–863 AD.[77]

It is surrounded at its upper part by 139 lusterware tiles (with a metallic sheen), each one is 21.1 centimetres square and they are arranged on the diagonal in a chessboard pattern. Divided into two groups, they are dated from the beginning of the second half of the ninth century but it is not determined with certainty whether they were made in Baghdad or in Kairouan by a Baghdadi artisan, the controversy over the origin of this precious collection agitates the specialists. These tiles are mainly decorated with floral and plant motifs (stylised flowers, palm leaves and asymmetrical leaves on bottom hatch and checkered) belong to two series: one polychrome characterised by a greater richness of tones ranging from light gold to light, dark or ocher yellow, and from brick-red to brown lacquer, the other monochrome is a beautiful luster that goes from smoked gold to green gold. The coating around them is decorated with blue plant motifs dating from the eighteenth century or the first half of the nineteenth century. The horseshoe arch of the mihrab, stilted and broken at the top, rest on two columns of red marble with yellow veins, which surmounted with Byzantine style capitals that carry two crossbeams carved with floral patterns, each one is decorated with a Kufic inscription in relief.

The wall of the mihrab is covered with 28 panels of white marble, carved and pierced, which have a wide variety of plant and geometric patterns including the stylised grape leaf, the flower and the shell. Behind the openwork hint, there is an oldest niche on which several assumptions were formulated. If one refers to the story of Al-Bakri, an Andalusian historian and geographer of the eleventh century, it is the mihrab which would be done by Uqba Ibn Nafi, the founder of Kairouan, whereas Lucien Golvin shares the view that it is not an old mihrab but hardly a begun construction which may serve to support marble panels and either goes back to work of Ziadet Allah I (817–838) or to those of Abul Ibrahim around the years 862–863.[78] Above the marble cladding, the mihrab niche is crowned with a half dome-shaped vault made of manchineel bentwood. Covered with a thick coating completely painted, the concavity of the arch is decorated with intertwined scrolls enveloping stylised five-lobed vine leaves, three-lobed florets and sharp clusters, all in yellow on midnight blue background.[75]

The minbar, situated on the right of the mihrab, is used by the imam during the Friday or Eids sermons, is a staircase-shaped pulpit with an upper seat, reached by eleven steps, and measuring 3.93 metres' length to 3.31 metres in height. Dated from the ninth century (about 862) and erected under the reign of the sixth Aghlabid ruler Abul Ibrahim (856–863), it is made in teak wood imported from India.[79] Among all the pulpits of the Muslim world, it is certainly the oldest example of minbar still preserved today.[80] Probably made by cabinetmakers of Kairouan (some researchers also refer to Baghdad), it consists of an assembly of more than 300 finely carved wood pieces with an exceptional ornamental wealth (vegetal and geometric patterns refer to the Umayyad and Abbasid models), among which about 90 rectangular panels carved with plenty of pine cones, grape leaves, thin and flexible stems, lanceolate fruits and various geometric shapes (squares, diamonds, stars, etc.). The upper edge of the minbar ramp is adorned with a rich and graceful vegetal decoration composed of alternately arranged foliated scrolls, each one containing a spread vine-leaf and a cluster of grapes. In the early twentieth century, the minbar had a painstaking restoration. Although it has existed for more than eleven centuries, all panels, with the exception of nine, are originals and are in a good state of conservation, the fineness of the execution of the minbar makes it a great masterpiece of Islamic wood carving referring to Paul Sebag.[81] This old chair of the ninth century is still in its original location, next to the mihrab.

Maqsura

The maqsura, located near the minbar, consists of a fence bounding a private enclosure that allows the sovereign and his senior officials to follow the solemn prayer of Friday without mingling with the faithful. Jewel of the art of woodwork produced during the reign of the Zirid prince Al-Mu'izz ibn Badis and dated from the first half of the eleventh century, it is considered the oldest still in place in the Islamic world. It is a cedar wood fence finely sculpted and carved on three sides with various geometric motifs measuring 2.8 metres tall, eight metres long and six metres wide.[82] Its main adornment is a frieze that crowns calligraphy, the latter surmounted by a line of pointed openwork merlons, features an inscription in flowery kufic character carved on the background of interlacing plants. Carefully executed in relief, it represents one of the most beautiful epigraphic bands of Islamic art.[82]

The library is near located, accessible by a door which the jambs and the lintel are carved in marble, adorned with a frieze of floral decoration. The library window is marked by an elegant setting that has two columns flanking the opening, which is a horseshoe arch topped by six blind arches and crowned by a series of berms sawtooth.[83]

Artworks

The Mosque of Uqba, one of the few religious buildings of Islam has remained intact almost all of its architectural and decorative elements, is due to the richness of its repertoire which is a veritable museum of Islamic decorative art and architecture. Most of the works on which rests the reputation of the mosque are still conserved in situ while a certain number of them have joined the collections of the Raqqada National Museum of Islamic Art; Raqqada is located about ten kilometres southwest of Kairouan.

From the library of the mosque comes a large collection of calligraphic scrolls and manuscripts, the oldest dating back to the second half of the ninth century. This valuable collection, observed from the late nineteenth century by the French orientalists Octave Houdas and René Basset who mention in their report on their scientific mission in Tunisia published in the Journal of African correspondence in 1882, comprises according to the inventory established at the time of the Hafsids (circa 1293–1294) several Qur'ans and books of fiqh that concern mainly the Maliki fiqh and its sources. These are the oldest fund of Maliki legal literature to have survived.[84]

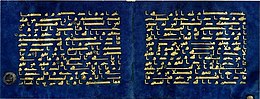

Among the finest works of this series, the pages of the Blue Qur'an, currently exhibited at Raqqada National Museum of Islamic Art, from a famous Qur'an in the second half of the fourth century of the Hijrah (the tenth century) most of which is preserved in Tunisia and the rest scattered in museums and private collections worldwide. Featuring kufic character suras are written in gold on vellum dyed with indigo, they are distinguished by a compact graph with no marks for vowels. The beginning of each surah is indicated by a band consisting of a golden stylised leafy foliage, dotted with red and blue, while the verses are separated by silver rosettes. Other scrolls and calligraphic Qur'ans, as that known as the Hadinah's Qur'an, copied and illuminated by the calligrapher Ali ibn Ahmad al-Warraq for the governess of the Zirid prince Al-Muizz ibn Badis at about 1020 AD, were also in the library before being transferred to Raqqada museum. This collection is a unique source for studying the history and evolution of calligraphy of medieval manuscripts in the Maghreb, covering the period from the ninth to the eleventh century.

Other works of art such as the crowns of light (circular chandeliers) made in cast bronze, dating from the Fatimid-Zirid period (around the tenth to the early eleventh century), originally belonged to the furniture of the mosque. These polycandelons, now scattered in various Tunisian museums including Raqqada, consist of three chains supporting a perforated brass plate, which has a central circular ring around which radiate 18 equidistant poles connected by many horseshoe arches and equipped for each of two landmarks flared. The three chains, connected by a suspension ring, are each fixed to the plate by an almond-shaped finial. The crowns of light are marked by Byzantine influence to which the Kairouanese artisan brought the specificities of Islamic decorative repertoire (geometric and floral motifs).[85]

Role in Muslim civilisation

At the time of its greatest splendor, between the ninth and eleventh centuries AD, Kairouan was one of the greatest centres of Islamic civilisation and its reputation as a hotbed of scholarship covered the entire Maghreb. During this period, the Great Mosque of Kairouan was both a place of prayer and a centre for teaching Islamic sciences under the Maliki current. One may conceivably compare its role to that of the University of Paris during the Middle Ages.[86]

In addition to studies on the deepening of religious thought and Maliki jurisprudence, the mosque also hosted various courses in secular subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine and botany. The transmission of knowledge was assured by prominent scholars and theologians which included Sahnun ibn Sa'id and Asad ibn al-Furat, eminent jurists who contributed greatly to the dissemination of the Maliki thought, Ishaq ibn Imran and Ibn al-Jazzar in medicine, Abu Sahl al-Kairouani and Abd al-Monim al-Kindi in mathematics. Thus, the mosque, headquarters of a prestigious university with a large library containing a large number of scientific and theological works, was the most remarkable intellectual and cultural centre in North Africa during the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries.[87]

35°40′53″N 10°06′14″E / 35.68139°N 10.10389°E

See also

- List of the oldest mosques

- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

- Minar (Firuzabad)

- Moorish Mosque, Kapurthala

References

- ^ || Géotunis 2009 :: Kairouan ||

- ^ Great Mosque of Kairouan (discoverislamicart.org) Archived 2013-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Great Mosque of Kairouan – Kairouan, Tunisia". Archived from the original on 2019-08-15. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "Kairouan – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Archived from the original on 2022-08-23. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- ^ "Kairouan 499" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- ^ The Great Mosque (kairouan-cci2009.nat.tn)[dead link][permanent dead link]

- ^ (in French) M’hamed Hassine Fantar, De Carthage à Kairouan: 2000 ans d’art et d’histoire en Tunisie, éd. Agence française d’action artistique, Paris, 1982, p. 23

- ^ Wilfrid Knapp and Nevill Barbour, North West Africa : a political and economic survey, Editions Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1977, page 404

- ^ Henri Saladin, Tunis et Kairouan, Editions Henri Laurens, Paris, 1908, page 118

- ^ Mahmud Abd al-Mawla, L’université zaytounienne et la société tunisienne, éditions Maison Tiers-Monde, Tunis, 1984, page 33

- ^ Kerrou, Mohamed (September 10, 1998). "Quartiers et faubourgs de la médina de Kairouan. Des mots aux modes de spatialisation". Genèses. Sciences sociales et histoire. 33 (1): 49–76. doi:10.3406/genes.1998.1539 – via www.persee.fr.

- ^ a b c d e "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 8

- ^ a b (in French) Henri Saladin, Tunis et Kairouan, coll. Les Villes d’art célèbres, éd. Henri Laurens, Paris, 1908, p. 120

- ^ Amédée Guiraud, Histoire de la Tunisie : les expéditions militaires arabes du VIIe au IXe siècle, éd. SAPI, Tunis, 1937, p. 48

- ^ Jack Finegan, The archeology of world religions, vol. III, ed. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1965, p. 522

- ^ Paul Sebag, La Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, éd. Robert Delpire, Paris, 1963, p. 25

- ^ Djait, Hichem (September 10, 1973). "L'Afrique arabe au VIIIe siècle (86-184 H./705-800)". Annales. 28 (3): 601–621. doi:10.3406/ahess.1973.293371. S2CID 162217635 – via www.persee.fr.

- ^ Archéologie méditerranéenne, n°1–2, 1965, p. 163

- ^ "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- ^ Razia Grover Mosques, p. 52, New Holland, 2007 ISBN 1-84537-692-7, ISBN 978-1-84537-692-5.

- ^ a b c Golvin, Lucien (September 10, 1968). "Quelques réflexions sur la grande mosquée de Kairouan à la période des Aghlabides". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 5 (1): 69–77. doi:10.3406/remmm.1968.982 – via www.persee.fr.

- ^ Alexandre Papadopoulo, Islam and Muslim art, ed. Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1979, p. 507

- ^ a b c "Soha Gaafar et Marwa Mourad, « La Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, un maillon clé dans l'histoire de l'architecture », Le Progrès égyptien, 29 octobre 2005, p. 3" (PDF) (in French).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 40

- ^ Georges Marçais, L’architecture : Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc, Espagne, Sicile, vol. I, éd. Picard, Paris, 1927, p. 12

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 32

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 53

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 59

- ^ "Jacques Vérité, Conservation de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, éd. Unesco, Paris, 1981" (PDF) (in French). (1.40 MB)

- ^ "Mahmoud Bouali, « Il y a près de trois siècles, un tourisme éminemment éclairé », La Presse de Tunisie, date inconnue".

- ^ "Courte biographie sur Thomas Shaw (Société des anglicistes de l'enseignement supérieur)". Archived from the original on August 13, 2010.

- ^ (in French) Kairouan n’était pas une ville interdite (Capitale de la culture islamique 2009)[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mohamed Bergaoui, Tourisme et voyages en Tunisie : les années régence, éd. Simpact, Tunis, 1996, p. 231

- ^ (in French) The influence of Kairouan on art and literature (Capital of Islamic culture 2009)[permanent dead link]

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 9

- ^ "Fragment de bois à décor d'arcatures d'époque hafside (Qantara)". Archived from the original on October 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 10

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 85

- ^ Harrison, Peter (September 10, 2004). Castles of God: Fortified Religious Buildings of the World. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843830665 – via Google Books.

- ^ (in French) Henri Saladin, Tunis et Kairouan, p. 122

- ^ "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 102

- ^ a b "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013.

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 90

- ^ a b Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 97

- ^ a b Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 15

- ^ a b Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 13

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 14

- ^ a b "Minaret de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on July 7, 2010.

- ^ Ahmad Fikri, L’art islamique de Tunisie : la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, vol. II, éd. Henri Laurens, Paris, 1934, p. 114

- ^ Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (September 10, 2002). Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : an Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070048 – via Google Books.

- ^ Michael Grant, Dawn of the Middle Ages, ed. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1981, p. 81

- ^ "Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- ^ "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013.

- ^ Georges Marçais, Coupole et plafonds de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, éd. Tournier, Paris, 1925, p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- ^ "Présentation de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Georges Marçais, L’architecture : Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc, Espagne, Sicile, vol. I, p. 140

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 34

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 33

- ^ Henri Saladin, Tunis et Kairouan, p. 124

- ^ Georges Marçais, L’architecture : Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc, Espagne, Sicile, vol. II, p. 897

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 28

- ^ (in French) Monuments de Kairouan (Strabon.org) Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Revue de géographie, vol. 8, éd. Charles Delagrave, Paris, 1989, p. 396

- ^ Centre italien d’études du haut Moyen Âge, Ideologie e pratiche del reimpiego nell’alto Medioevo: 16–21 aprile 1998. Volume 2, éd. Presso La Sede del Centro, Spolète, 1999, p. 815

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; Boda, Sharon La; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (September 10, 1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781884964039 – via Google Books.

- ^ Christian Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshak, Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee, ed. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, 1980, pp. 15–20 (figure 20)

- ^ Actualité des religions, n°12–22, 2000, p. 64

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 35

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 42

- ^ "Présentation de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan (ArchNet)". Archived from the original on November 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Reduslim - 4 Orte, an denen Sie dieses wunderbare Produkt kaufen können - 24go". www.24go.me. January 27, 2022.

- ^ "Mihrab of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Burckhardt, Titus (September 10, 2009). Art of Islam: Language and Meaning. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 9781933316659 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lucien Golvin, « Le mihrab de Kairouan », Kunst des Orients, vol. V, 1969, pp. 1–38

- ^ "Minbar of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- ^ Mohammad Adnan Bakhit, History of humanity, Routledge, 2000, page 345

- ^ Paul Sebag, op. cit., p. 105

- ^ a b "Maqsura of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara)". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Néji Djelloul, op. cit., p. 57

- ^ Weiss, Bernard G. (September 10, 2002). Studies in Islamic Legal Theory. BRILL. ISBN 9004120661 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Circular chandelier - Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org.

- ^ Henri Saladin, Tunis et Kairouan, p. 118

- ^ "Nurdin Laugu, « The Roles of Mosque Libraries through History », Al-Jami'ah, vol. 45, n°1, pages 103 and 105, 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011.

Further reading

- Néji Djelloul, 2000. Kairouan, the Great Mosque. Editions Contrastes.

- Paul Sebag, 1965. Great Mosque of Kairouan. New York Macmillan.

- John D. Hoag, 1987. Islamic architecture. Rizzoli.

- Jonathan M. Bloom, 2002. Early Islamic art and architecture. Ashgate.

- G. T. Rivoira, 2009, Moslem Architecture. Its Origins and Development. ASLAN PR.