Green Dome

| Green Dome | |

|---|---|

Al-Qubbah Al-Khaḍrāʾ (ٱَلْقُبَّة ٱلْخَضْرَاء) | |

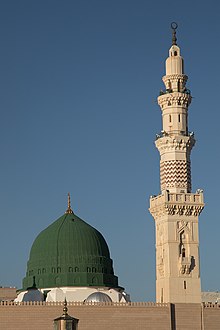

The Green Dome at the Prophet's Mosque and the Bab Al-Baqi' minaret | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Region | Al-Madinah Province |

| Rite | Ziyarat |

| Leadership | President of the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques: Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais |

| Location | |

| Location | Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Medina, Hejaz, Saudi Arabia |

| Administration | The Agency of the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques |

| Geographic coordinates | 24°28′03.22″N 039°36′41.18″E / 24.4675611°N 39.6114389°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Tomb |

| Founder | Mamluk Sultan Al Mansur Qalawun[1] |

| Date established | 678 A.H. / 1279 C.E.[2][1] |

| Completed | 678 A.H. / 1279 C.E.[2][1] |

| Materials | Wood,[3] brick[4] |

The Green Dome (Arabic: ٱَلْقُبَّة ٱلْخَضْرَاء, romanized: al-Qubbah al-Khaḍrāʾ, Hejazi Arabic pronunciation: [al.ɡʊb.ba al.xadˤ.ra]) is a green-coloured dome built above the tombs of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the early Rashidun Caliphs Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) and Omar (r. 634–644), which used to be the Noble Chamber of Aisha. The dome is located in the southeast corner of Al-Masjid al-Nabawi in Medina, present-day Saudi Arabia.[5] Millions visit it every year, since it is a tradition to visit the mosque after or before the pilgrimage to Mecca.

The structure dates back to 1279 C.E., when an unpainted wooden cupola was built over the tomb. It was later rebuilt and painted using different colours (blue and silver) twice in the late 15th century and once in 1817. The dome was first painted green in 1837, and hence became known as the "Green Dome".[2]

History

[edit]

Built in 1279 C.E. or 678 A.H., during the reign of Mamluk Sultan Al Mansur Qalawun,[1] the original structure was made out of wood and was colourless,[3] painted white and blue in later restorations. After a serious fire struck the Mosque in 1481, the mosque and dome had been burnt and a restoration project was initiated by Sultan Qaitbay who had most of the wooden base replaced by a brick structure in order to prevent the collapse of the dome in the future, and used plates of lead to cover the new wooden dome. The building, including the Tomb of the Prophet, was extensively renewed through Qaitbay's patronage.[4] The current dome was added in 1818 by the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II.[5] The dome was first painted green in 1837.[2]

When Saud bin Abdul-Aziz took Medina in 1805, his followers, the Wahhabis, demolished nearly every tomb dome in Medina based on their belief that the veneration of graves and places claimed to possess supernatural powers is an offense against the oneness of God (tawhid) and supposedly associates partners with Him (shirk).[6] The tomb was stripped of its gold and jewel ornaments, but the dome was preserved either because of an unsuccessful attempt to demolish its hardened structure, or because some time ago Ibn Abd al-Wahhab wrote that he did not wish to see the dome destroyed despite his aversion to people praying at the tomb.[7] Similar events took place in 1925 when the Saudi militias retook—and this time managed to keep—the city.[8][9][10] Most of the famous Muslim scholars of the Wahhabi Sect support the decision made by Saudi authorities not to allow veneration of the tomb as it was built much later after the death of Muhammad and considered it as an "innovation" (bid'ah sayyi’ah).[11]

Tomb of Muhammad and early caliphs

[edit]Muhammad's grave lies within the confines of what used to be his and his wife Aisha's house, during the Hijra. During his lifetime, it adjoined the mosque. The first and second Rashidun Caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar are buried next to Muhammad. Umar was given a spot next to Abu Bakr by Aisha, originally intended for her. The mosque was expanded during the reign of Umayyad Caliph al-Walid I to include their tombs.[2] The graves themselves cannot be seen, as a gold mesh and black curtains cordon off the area.[12]

The graves and what remains of Aisha's house are enclosed by a 5-sided wall, without doors or windows, built by the caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz. The irregular pentagon shape was chosen deliberately, to make it look different from the rectangular Kaaba, and to discourage people from performing tawaf around it. The enclosure has been inaccessible since Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay's reconstruction of 1481. Only the outer southern wall, draped in green cloth, can be seen through the grilles built several centuries later.[citation needed]

Panorama

[edit]

Gallery

[edit]-

View from the western side of the Hujra

-

17th century bronze coin depicting Mamluk era dome which preceded the current dome

-

The Green Dome, in Burton's Pilgrimage, c. 1850 CE

-

The Dome, first photographed in 1880 by Muhammad Sadiq

-

The grave of Muhammad located inside the quarter seen here

See also

[edit]- Bayt al-Mawlid, the house where Muhammad is believed to have been born

- Burial places of founders of world religions

- Destruction of early Islamic heritage sites in Saudi Arabia

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Prophet's Mosque". ArchNet. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Ariffin, Syed Ahmad Iskandar Syed (2005). Architectural Conservation in Islam: Case Study of the Prophet's Mosque. Penerbit UTM. pp. 88–89, 109. ISBN 978-9835203732.

- ^ a b "The history of Green Dome in Madinah and its ruling". Peace Propagation Center. 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b Meinecke, Michael (1993). Mamlukische Architektur (in German). Vol. 2. pp. 396–442.

- ^ a b Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-0203203873.

- ^ Peskes, Esther (2000). "Wahhābiyya". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 11 (2nd ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 40, 42. ISBN 9004127569.

- ^ Mark Weston (2008). Prophets and princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the present. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0470182574.

- ^ Mark Weston (2008). Prophets and princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the present. John Wiley and Sons. p. 136. ISBN 978-0470182574.

- ^ Vincent J. Cornell (2007). Voices of Islam: Voices of the spirit. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 84. ISBN 978-0275987343.

- ^ Carl W. Ernst (2004). Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-0807855775.

- ^ "Kya gumbad e Khazra ko gira dena chahye Reply to Bol TV Ulamaa | Engineer Muhammad Ali Mirza". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 13 December 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Important Sites: The Prophet's Mosque". Inside Islam. 16 February 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2018.