Karl Drais

Karl Freiherr von Drais | |

|---|---|

Karl Drais, c. 1820, then still a baron | |

| Born | Karl Friedrich Christian Ludwig Freiherr Drais von Sauerbronn 29 April 1785 Karlsruhe, Baden-Württemberg, Germany |

| Died | 10 December 1851 (aged 66) Karllsruhe, Baden-Württemberg, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Inventor |

Karl Freiherr von Drais (full name: Karl Friedrich Christian Ludwig Freiherr Drais von Sauerbronn) (29 April 1785 – 10 December 1851) was a noble German forest official and significant inventor in the Biedermeier period. He was born and died in Karlsruhe.

He is seen as "the father of the bicycle".[1]

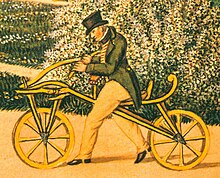

Bicycle

Drais was a prolific inventor, who invented the Laufmaschine ("running machine"),[2] also later called the velocipede, draisine (English) or Parisienne (French), also nicknamed the hobby horse or dandy horse. This was his most popular and widely recognized invention. It incorporated the two-wheeler principle that is basic to the bicycle and motorcycle and was the beginning of mechanized personal transport.[3] This was the earliest form of a bicycle, without pedals. His first reported ride from Mannheim to the "Schwetzinger Relaishaus" (a coaching inn, located in "Rheinau", today a district of Mannheim) took place on 12 June 1817 using Baden's best road. Karl rode his bike;[4] it was a distance of about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi). The round trip took him a little more than an hour but may be seen as the big bang for horseless transport. However, after marketing the velocipede, it became apparent that roads were so rutted by carriages that it was hard to balance on the machine for long, so velocipede riders took to the pavements (sidewalks) and moved far too quickly, endangering pedestrians. Consequently, authorities in Germany, Great Britain, the United States, and even Calcutta banned its use, which ended its vogue for decades.[5]

Other inventions

Drais also invented the earliest typewriter with a keyboard (1821). He later developed an early stenograph machine which used 16 characters (1827), a device to record piano music on paper (1812), the first meat grinder (1840s), and a wood-saving cooker including the earliest hay chest. He also invented two four-wheeled human powered vehicles (1813/1814), the second of which he presented in Vienna to the congress carving up Europe after Napoleon's defeat.[6] In 1842, he developed a foot-driven human powered railway vehicle whose name "draisine" is used even today for railway handcars.[5]

Time as civil servant

Drais was unable to market his inventions for profit because he was still a civil servant of Baden, even though he was being paid without providing active service. As a result, on 12 January 1818, Drais was awarded a grand-ducal privilege (Großherzogliches Privileg) to protect his inventions for 10 years in Baden by the younger Grand Duke Karl.[7] Grand Duke Karl also appointed Drais professor of mechanics. This was merely an honorary title, not related to any university or other institution. Drais retired from the civil service and was awarded a pension for his appointment to professor of mechanical science.[5]

Upheaval

In 1820, trouble overtook Drais when the political murder of the author August von Kotzebue was followed by the beheading of the perpetrator, Karl Ludwig Sand. In 1822, Drais was a fervent liberal who supported revolution in Baden. Drais's conservative father, as the highest Judge of Baden, had not entered a plea for pardon in the beheading of Karl Ludwig Sand, and the younger Drais was mobbed by the student partisans everywhere in Germany due to his family ties. Therefore, Drais emigrated to Brazil where he lived from 1822 to 1827, and worked as a land surveyor on the fazenda of Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff. In 1827, he returned to Mannheim. Three years later in 1830, Drais's father died and the younger Drais was mobbed by jealous rivals.[5]

In 1839, after surviving a murderous attack in 1838, he moved to the village of Waldkatzenbach in the hills of Odenwald and remained there until 1845. During this period, he invented the railway handcar (later known as the draisine). Finally, he moved back to his place of birth, Karlsruhe. In 1849, and still a fervent radical, Drais gave up his title of Baron and dropped the "von" from his name. Subsequently, after the revolution collapsed, he was in a very bad position. The royalists tried to have him certified as mad and locked up. His pension was confiscated to help to pay for the "costs of revolution" after it was suppressed by the Prussians.[8]

Death

Drais's undoing had been the fact that he had publicly renounced his noble title in 1848, and adopted the name "Citizen Karl Drais" as a tribute to the French Revolution.[citation needed]

Karl Drais died penniless on 10 December 1851 in Karlsruhe.[7] The house in which he lived last is just two blocks away from where at that time a young Carl Benz was raised.[citation needed]

In 1985, West Germany issued a commemorative postage stamp, a semipostal 50 Pf+25 Pf surcharge, in remembrance of the 200th anniversary of Karl Drais's birthday.[5]

In 2017, Germany issued a commemorative postage stamp (0,70 Euro) in remembrance of the 200th anniversary of Karl Drais's first run of his "running machine" on 12 June 1817. The stamp shows the machine plus as its shadow, a bicycle.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "200 years since the father of the bicycle Baron Karl von Drais invented the 'running machine' | Cycling UK".

- ^ "200 years since the father of the bicycle Baron Karl von Drais invented the 'running machine' | Cycling UK". www.cyclinguk.org. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Writer 2017-08-30T02:30:00Z, Elizabeth Palermo-Staff. "Who Invented the Bicycle?". livescience.com. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ e.V, Deutsche Zentrale für Tourismus. "The draisine invented by Karl Drais. The archetype of the modern-day bicycle". www.Germany.travel. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Karl Drais-The New Biography by Dr. Hans-Erhard Lessing

- ^ "Did you know that Karl Drais…". 6 May 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b Hüttmann, Gerd. "Karl Drais biography" (PDF). ADFC Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club.

- ^ "Karl von Drais". www.cyclemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- Hans-Erhard Lessing: Karl Drais – zwei Räder statt vier Hufe. G. Braun Buchverlag, Karlsruhe 2010. ISBN 978-3-7650-8569-7

- Hans-Erhard Lessing: Automobilität – Karl Drais und die unglaublichen Anfänge. Maxime-Verlag, Leipzig 2003. ISBN 3-931965-22-8

- Hermann Ebeling: Der Freiherr von Drais: das tragische Leben des „verrückten Barons“. Ein Erfinderschicksal im Biedermeier. Braun, Karlsruhe 1985. ISBN 3-7650-8045-4

- Heinz Schmitt: Karl Friedrich Drais von Sauerbronn: 1785–1851; ein badischer Erfinder; Ausstellung zu seinem 200. Geburtstag; Stadtgeschichte im Prinz-Max-Palais, Karlsruhe, 9. März-26. Mai 1985; Städt. Reiss-Museum Mannheim, 5. Juli–18. August 1985. Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe 1985.

- Michael Rauck: Karl Freiherr Drais von Sauerbronn: Erfinder und Unternehmer (1785–1851). Steiner, Stuttgart 1983. ISBN 3-515-03939-2

- Karl Hasel: Karl Friedrich Frhr. Drais von Sauerbronn, in Peter Weidenbach (Red.): Biographie bedeutender Forstleute aus Baden-Württemberg. Schriftenreihe der Landesforstverwaltung Baden-Württemberg, Band 55. Herausgegeben vom Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Umwelt Baden-Württemberg. Landesforstverwaltung Baden-Württemberg und Baden-Württembergische Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt, Stuttgart und Freiburg im Breisgau 1980, pp. 99–109.

External links

- "Brimstone and Bicycles" by Mick Hamer of New Scientist, 29 January 2005

- www.karldrais.de by S. Fink and H. E. Lessing (choose English version)

- Karl Drais in Baden-Baden by Hans-Erhard Lessing