Llwyngwern quarry

One of the quarry's original buildings, re-used by the Centre for Alternative Technology | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

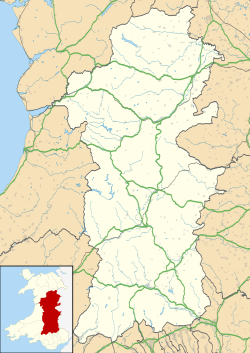

Location in Powys | |

| Location | near Pantperthog |

| County | Montgomeryshire (now Powys) |

| Country | Wales, UK |

| Coordinates | 52°37′25″N 3°50′26″W / 52.623502°N 3.840429°W grid reference SH 754 044 |

| Production | |

| Products | Slate |

| Type | Quarry |

| History | |

| Opened | 1828 |

| Active | 1828–1840s; 1853–July 1903; 1905–1910; 1920–1937; 1938–1941 |

| Closed | 1941 |

The Llwyngwern quarry (sometimes known as Glandulas quarry[1] or Maglona quarry) was a slate quarry in Wales that opened by 1828 and continued working until about 1950.[2] The quarry is located on the western flank of Mynydd Llwyn-gwern.

History

[edit]Llwyngwern was a small quarry that only briefly produced more than 2000 tons of finished slate per year. It worked a minor outcropping of slate away from the main veins quarried to the north around Corris and Aberllefenni.[2]

Early history

[edit]The quarry began working no later than 1828, when Joseph Tyler was appointed the quarry manager; he was the son of the manager of Diffwys quarry in Blaenau Ffestiniog.[3] In 1835, the quarry was owned by Simon Cook of Llwyngwern, though it closed in the 1840s.[4]

In 1853 it was re-opened by W.R. Williams of Dolgellau and was described as a well-developed quarry with a 30 feet (9.1 m) waterwheel powering the mill.[1] In 1863, a new company, the Llwyngwern Slate Quarry Co. Ltd, was formed to work the quarry, under the ownership of John Lloyd Jones of Nantlle,[5] but this company failed in 1866. The company was taken over in 1866 by H. J. Standly but only worked on a modest scale.[1] By 1878, the quarry was owned by the Llwyngwern Slate and Slab Quarry.[4]

Late 19th century

[edit]In 1883, 35 men were working at the quarry.[1] By 1887, the quarry had dammed the local stream to form a header reservoir for the various waterwheels on the site, including one for the main mill. The quarry was in the form of a deep open pit, accessed by a tunnel at the mill level. A row of workers' cottages had been built beside the Afon Dulas and a gunpowder magazine was located north-west of the mill.[4] The quarry was then owned by David Lloyd Jones, who specialised in supplying slab for enamelling, both to a merchant in London and to a joint venture with the Towyn Enamelled Slate Quarry Company.[1] Jones sold Llwyngwern in 1891.[6]

In 1893, a new company Maglona Quarries Ltd. took over Llwyngwern,[7] (Maglona was commonly believed to be the name of a Roman fort on Sarn Helen at what is now Machynlleth[8]) In March 1895, quarryman Robert Ellis Jones was killed at the quarry when the rock face he was working on collapsed.[9]

In 1896,[4] the quarry was connected to the Corris Railway by a short branch from Llwyngwern railway station, which crossed the Afon Dulas on a timber viaduct.[10]

Before the First World War

[edit]

In 1900, the quarry employed 144 workers. By this time the open pit was much deeper, and a new tunnel had been bored connecting the bottom of the pit to the Corris Railway branch, below mill level. An incline was built from the mill level down to the branch – this incline was unusual because it had to be powered to lift rock up to the mill – in most quarries, the mill was built lower than the pit to avoid this extra cost. The incline was a water balance that used large tanks to counter-balance the weight of the ascending wagons.[4] There were newspaper reports in September of that year that Maglona Quarries had agreed to purchase Ratgoed Quarry and re-open it,[11] however these were soon denied.[12]

1902 was one of the quarry's most productive years, delivering 2087 tons of slab and finished mantlepieces.[1] There was a fatal accident at Llwyngwern in March 1903, killing William Thomas, of Abergarfan. At the inquest into his death, Dr. Williams said his injuries "were too frightful to describe".[13] This accident resulted in enquiries by the Board of Trade, and as a result the quarry closed in July 1903, causing much consternation as it was "the chief industry of the district". Many of the men who lost their jobs left to find work in the coal mines of South Wales.[14] This was the end of the Maglona Quarry company.

The quarry re-opened in 1905, managed by D. Hughes and employing around 60 men.[15] In 1906 there was another fatal accident, when 19-year-old Henry Rees who had been working in the mill fell while walking through the tunnel to the main pit. He was crossing a wooden bridge when he slipped and fell 50 feet (15 m) head-first into a shaft.[16] He died almost instantly.[17]

Slate quarries produce a large amount of waste rock, and there was limited room at Llwyngwern to dispose of this waste. In 1906, an aerial ropeway was installed to lift waste rock from the bottom of the exit incline up the mountainside to a site south-west of the quarry reservoir. A stationary steam engine at the upper end of the ropeway provided the power.[4]

By 1909, employment at Llwyngwern was down to 33, and the company sold the lease to Sydney Fowler Wright. But Wright was unable to pay the lease due on the quarry and in early 1910 the owners, the Vanes Estate, closed the quarry and forced an auction of the equipment to recover the money owed to them. There was some dispute over who actually owned the lease and the equipment. The quarry appears not to have worked again until after the First World War.[1]

Between the wars

[edit]The quarry re-opened in 1920, employing 18 men.[1] A suction gas stationary engine was installed to drive the quarry machinery.[18]

The timber viaduct that carried the Corris Railway branch over the Dulas was declared unsafe in the 1920s and the quarry, unwilling to pay for repairs, became the first one to stop using the railway and instead transport its output to Machynlleth by road.[10]

In 1924, the local company of Hall Harber & Thomas Ltd. purchased Llwyngwern. They also purchased the Ratgoed quarry,[19] finally completing the transaction that had been proposed in 1900. In 1931 the quarry still employed 28 men,[2] but it was sold to the Grantham Slate Works Ltd. in 1934.[1] They only last until 1937, when they closed the quarry and auctioned off the remaining equipment.

The quarry was purchased by a new Llwyngwern Slate Quarries Ltd. in 1938 and they worked the quarry with a handful of men, but all work ceased in 1941.[1]

Closure

[edit]After the Second World War G.S. Ellison took on the quarry and did some work. In 1953 he attempted to manufacture bricks from ground slate waste, but this was not successful. The remaining quarry equipment was scrapped in 1959.[4]

Reuse

[edit]After closure the quarry was disused until 1972, when it became the site for an experiment in green living.[20] This has now developed into the Centre for Alternative Technology, which occupies much of the quarry site.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Richards, Alun John (1994). Slate Quarrying at Corris. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-279-1.

- ^ a b c The Corris Railway Society (1988). A Return to Corris. Avon-Anglia Publications & Services. ISBN 978-0905466897.

- ^ David Gwyn (6 May 2015). Welsh Slate: Archaeology and History of an Industry. RCAHMW. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-871184-55-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Parry, Claire (14 June 2011). "Llwyngwern Slate Quarry (407582)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Llwyngwern – gwaredigaeth gyfyng i gannoedd o Bersonnau!!!". Papurau Newydd Cymru Arlein. 10 December 1869.

- ^ "Local Law Case". Papurau Newydd Cymru Arlein. 28 May 1891.

- ^ "Maglona Quarries Ltd" (1893). General archive, ID: BT 31/5659/39500 39500. National Archives.

- ^ Evan Jones (2009). A Portrait of Machynlleth and Its Surroundings. Coch Y Bonddu Books. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-904784-24-1.

- ^ "Quarry Fatality at Llwyn-gwern". The Montgomery County Times. 9 March 1895.

- ^ a b Alun John Richards (2001). The Slate Railways of Wales. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 978-0-86381-689-5.

- ^ "Corris". Papurau Newydd Cymru Arlein. 21 September 1900.

- ^ "Aberllefenni". Papurau Newydd Cymru Arlein. 5 October 1900.

- ^ "Machynlleth. Fatal Accident". The Montgomeryshire Express and Radnor Times. 31 March 1903. p. 8.

- ^ "Machynlleth". Welsh Gazette. 2 July 1903. p. 4.

- ^ "Corris". Cambrian News. 16 June 1905.

- ^ "-Short cut that meant death". The Aberystwith Observer. 13 December 1906.

- ^ "Corris". Cambrian News. 14 December 1906.

- ^ David Gwyn (6 May 2015). Welsh Slate: Archaeology and History of an Industry. RCAHMW. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-871184-55-6.

- ^ Richards, Alun John (1994). Slate Quarrying at Corris. Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 978-0-86381-279-8.

- ^ Sugar News. Sugar News Press. 1979.

External links

[edit]The quarry's entry on the National Monuments Record of Wales (NMRW)'s website