Marin Temperica

Marin Temperica | |

|---|---|

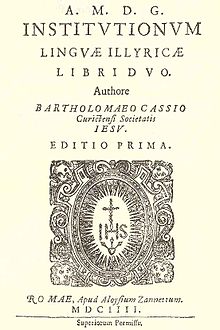

The first Slavic language grammar published by Bartol Kašić in Rome in 1604, based on the request of Marin Temperica | |

| Born | December 1534 |

| Died | 1591 or 1598 |

| Nationality | Ragusan |

| Other names | Marin Temparica, Marino Temparizza,[1] Marin Temperičić[2] |

| Occupation(s) | merchant, jesuit and linguist |

Marin Temperica or Marin Temparica (December 1534 – 1591/1598) was a 16th-century Ragusan merchant, Jesuit and linguist.[1] In 1551, after receiving basic education in Dubrovnik, he moved to Ottoman part of Balkans and spent 24 years working as a merchant. Temperica was one of the first chaplains of the Jesuit household in Istanbul. He returned to Dubrovnik in 1575 and continued his activities in Jesuit religious congregation of the Catholic Church.

Temperica understood the importance of the Slavic literary language understandable all over the Balkans for easier conversion of the schismatic population of Ottoman Empire. In 1582 he wrote a report to Jesuit general Claudio Acquaviva in which he insisted on publishing the Illyrian language dictionaries and grammars. He requested establishment of a seminary in Dubrovnik in which the Catholic religion would be taught in the Shtokavian dialect. His observations and requests were the basis for the first Slavic language grammar published by Bartol Kašić in Rome in 1604 and for the modern-day Croatian language standard.

Early life[edit]

Temperica was born in December 1534 in Dubrovnik, Republic of Ragusa.[3] In his youth he received some humanist education. In 1551 he moved to Ottoman part of Balkans and spent next 24 years working as merchant and earning substantial wealth.[4] Temperica was one of the first chaplains of the Jesuit household in Istanbul.[5] On 15 December 1567 Marin transcribed Hortulus animae from Latin to Cyrillic script.[6]

In 1575 Temperica returned to Dubrovnik, where he met two notable jesuits, Emericus de Bona and Julius Mancinellus.[4]

Report to Acquaviva[edit]

In 1582 Temperica wrote a report to general Claudio Acquaviva. In his 1582 report Temperica expressed similar views as in 1593 report of another Jesuit, Aleksandar Komulović.[7]

The Catholic Reformists believed that it was necessary to determine what would be the most understandable language version on the territory populated by South Slavs.[8] Temperica emphasized the importance of the Slavic literary language understandable all over the Balkans.[9] In the report, he uses the Latin term lingua sclavona (lit. "Slavonian language")[10] or scalavona (lit. Slavic language)[1] for the vernacular of Bosnia, Serbia and Herzegovina, while naming Church Slavonic as the literary language.[1][10] Temperica insisted on Shtokavian as most widespread on the Balkans.[11] He reported that the same language was spoken on the territory between Dubrovnik and Bulgaria, in Bosnia, Serbia and Herzegovina, being most appropriate basis for common South Slavic literary language.[10]

Serbian language and alphabet[edit]

Temperica believed that Serbian language spoken in Bosnia is the purest and most beautiful version of the Serbian language.[12][13] With his advice and activities Temperica helped Angelo Rocca to publish his 1591 Bibliotheca apostolica, in which he also published the Serbian alphabet.[14][15] Temperica wrote for Rocca the Catholic Lord's Prayer using the Cyrillic script, which he regularly refer to as "Alphabetum Servianum" and "Litterae Serbianae".[16]

Legacy[edit]

The idea about Illyrian language as tool for religious unification of South Slavs inspired Pope Clement VIII to insist that Claudio Acquaviva should research this language.[17] The result of Temperica's report to Acquaviva also includes the first Slavic language grammar published in 1604 in Rome in Latin by Bartol Kašić.[18] Although he was born as Chakavian speaker, Kašić opted for Shtokavian of Bosnia as the best choice because it was most widely spread.[19] Jakov Mikalja supported Kašić's position that dialect of Bosnia was the best variant of Illyrian (common South Slavic) language.[20] Mikalja adopted an official position toward this language held by Jesuits and Pope under the influence of Teperica, comparing the beauty of Bosnian dialect with the beauty of Tuscan dialect.[21]

Natko Nodilo explains that 1582 report of Temperica, in which he underlines the need for publishing of the Illyrian language dictionaries and grammars, is the earliest trace of Jesuit interest in Dubrovnik.[22] Temperica proposed the establishment of the seminary on the territory of the Dubrovnik Diocese, in which the Shtokavian dialect would be used. Temperica's ideas and initiatives were the basis of the modern Croatian language standard.[23]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d V. A. Fine 2010, p. 236.

- ^ Vanino, Miroslav (1936). Vrela i prinosi. Nova tiskara. p. 180.

Temperica (Temperičić) M.

- ^ Kosić, Ivan (1999). Bartol Kašić u Nacionalnoj i Sveučilišnoj Knjižnici u Zagrebu: zbornik radova o djelu Bartola Kašića. Nacionalna i Sveučilišna Knjižnica. p. 1. ISBN 978-953-6000-79-1.

dubrovački trgovac Marin Temperica (1534–1591) godine

- ^ a b Horvat, Vladimir (2004). Bartol Kašić--otac hrvatskoga jezikoslovlja. Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Hrvatski studiji-Studia Croatica. p. 61. ISBN 978-953-6682-49-2.

- ^ Stojković, Marijan; Samardžija, Marko (2005). Hrvatske jezične i pravopisne dvojbe. Pergamena. p. 109. ISBN 978-953-6576-19-7.

- ^ Ujević, Mate (1942). Hrvatska enciklopedija. Konzorcija Hrvatske enciklopedije. p. 194.

...Temperici (1534 — 98), da s čakavsko-kajkav- skog latiničkog predloška prepiše bosanskom ćirilicom poznato djelo Hortus animae (isp. Djela HA, knj. 31, str. XV — XCV).

- ^ V. A. Fine 2010, pp. 235, 236.

- ^ Vončina, Josip (1979). Filologija. Vol. 9. Jugoslovenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Odjel za filologiju. p. 19.

... ali se također odavno zna ne samo koje su potrebe nego i koji neposredni poticaji začeli protureformatorski interes za jezična pitanja: tražio se takav jezični tip koji bi mogao biti najboljim sredstvom za sporazumevanje na cijelome Slavenskome jugu.

- ^ Franičević, Marin (1986). Izabrana djela: Povijest hrvatske renesansne književnosti. Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske. p. 190.

Osnivanje Ilirskih zavoda u Loretu i Rimu, spomenica koju će Marin Temperica, pošto je stupio u isusovački red, uputiti generalu reda Aquavivi, o potrebi jedinstvenoga slavenskog jezika koji bi mogli razumjeti »po cijelom Balkanu« (1582), ...

- ^ a b c Gabrić-Bagarić, Darija (2010). "Četiri ishodišta hrvatskoga standardnoga jezika". FLUMINENSIA: Journal for Philological Research (in Croatian) (22). Department of Croatian language and literature of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Rijeka: 150.

- ^ Rad Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti. Akademija. 1992. p. 36.

Temperica ističe štokavski kao najrašireniji jezik na Balkanu.

- ^ Thesaurus pontificiarum sacrarumque antiquitatum. 1745. p. 250.

Bosina, inter ceteras Gentes Servianam linguam adhibentes, puriori & elegantiori loquendi forma venustatem Sevria non

- ^ Kolendić, Petar; Pantić, M. (1964). Iz staroga Dubrovnika. Srpska književna zadruga. p. 72.

(Bosina, inter ceteras Gentes Servianam linguam adhibentes, puriori & elegantiori loquendi forma venustatem Sevria non) Босна се међу осталим народима који употребљавају српски језик обичаје чистом и кићенијом формом у говору

- ^ Kolendić, Petar; Pantić, M. (1964). Iz staroga Dubrovnika. Srpska književna zadruga. p. 72.

Сарадњом и савјетом помагао му је, сјем других, Дубровчанин, исусовац Марин Темперица,...

- ^ Rocca, Angelo (1591). Bibliotheca apostolica vaticana a Sixto V,... in splendidiorem... locum translata et a fratre Angelo Roccha,... commentario variarum artium ac scientiarum materiis curiosis ac difficillimis, scituque dignis refertissimo illustrata... ex typogr. apostolica vaticana. p. 168.

- ^ Kolendić, Petar; Pantić, M. (1964). Iz staroga Dubrovnika. Srpska književna zadruga. p. 72.

па му је написао католички „оче наш" ћириловицом и исписао ћириловску азбуку, коју редовито зове „Alphabetum Serbianum" и „Litterae Serbianae"

- ^ Rad Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti. Akademija. 1992. p. 36.

- ^ Istoricheski pregled. Bŭlgarsko istorichesko druzhestvo. 1992. p. 9.

езуит Марин Темперица предава на генерала на езуитите в Рим, Клаудио Аквавива, предложение за възприемане на един език за славяните на Балканите. Плод на това искане е първата славянска граматика

- ^ Zadarska smotra. Matica hrvatska, Ogranak Zadar. 2007. p. 56.

Bartol Kašić, rođeni čakavac iz otoka Paga, zalaže se za bosansko štokavsko narječje ikavskog izgovora kao najbolje i najraširenije.

- ^ Rad. Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti. 1992. p. 36.

Kašićevu ideju o bosanskom kao najboljoj varijanti ilirskog jezika prihvaća i poznati leksikograf isusovac Jakov Mikalja.

- ^ Isusovci u Hrvata: zbornik radova međunarodnog znanstvenog simpozija "Isusovci na vjerskom, znanstvenom i kulturnom području u Hrvata". Filozofsko-teološki institut Družbe Isusove. 1992. p. 313.

Mikalja bosanski govor uspoređuje s ljepotom toskanskoga. U izboru jezične varijante Mikalja i della Bella preuzimaju službeni stav Isusovačkog reda i pape prema našem jeziku. Isusovački misionar Marin Temparica, na osnovi poznavanja...

- ^ Franičević, Marin (1974). Pjesnici i stoljeća. Mladost. p. 252.

Tako se dogodilo da je isusovac Marin Temperica već u XVI stoljeću pisao spomenicu o potrebi zajedničkog jezika, tražeći da se napiše rječnik i gramatika.

- ^ Katičić, Radoslav (1999). Na kroatističkim raskrižjima. Hrvatski studiji-Studia Croatica. p. 163. ISBN 9789536682065.

U sjemeništu kojega utemeljivanje na području dubrovačke nadbiskupije Temperica predlaže i preporučuje, učio bi se, dakako, i njegovao takav književni jezik. Iz toga je u dugotrajnu i ne uvijek ravnomjernu, niti u svemu jednako usmjerenu razvoju, potekao današnji hrvatski jezični standard.