Robert Cornelius

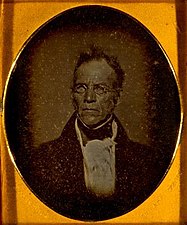

Robert Cornelius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 1, 1809 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 10, 1893 (aged 84) Frankford, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Photographer, lamp manufacturer |

| Spouse |

Harriet Comly

(m. 1832; d. 1884) |

| Children | 8 |

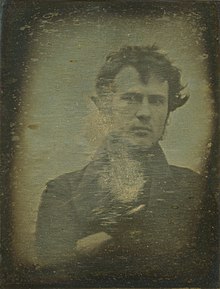

Robert Cornelius (/kɔːrˈniːliəs/; March 1, 1809[2] – August 10, 1893) was an American photographer and pioneer in the history of photography. He designed the photographic plate for the first photograph taken in the United States, an image of Central High School taken by Joseph Saxton in 1839. His self image taken in 1839 is the first known photographic portrait of a human taken in the United States. He operated two of the earliest photography studios in the United States between 1841 and 1843 and implemented innovative techniques to significantly reduce the exposure time required for portraits.

He was an inventor, businessman and lamp manufacturer. He created and patented the "solar lamp" in 1843 which burned brighter and allowed for the use of cheaper lard as a fuel source rather than more expensive whale oil.

Early life and career

Cornelius was born in Philadelphia to Sarah Cornelius (née Soder) and Christian Cornelius. His father immigrated from Amsterdam in 1783 and worked as a silversmith before opening a lamp-manufacturing company.[3][4] He attended private school as a youth and took a particular interest in chemistry.[5] In 1831, he began working for his father and specialized in silver plating and metal polishing. Soon after the daguerreotype was invented, Cornelius was approached by Joseph Saxton to create a silver plate for his daguerreotype of Central High School in Philadelphia. Saxton's photo is believed to be the oldest photograph taken in the United States.[6] It was this meeting that sparked Cornelius's interest in photography.[7]

With his own knowledge of chemistry and metallurgy, as well as the help of chemist Paul Beck Goddard, Cornelius attempted to perfect the daguerreotype. Around October 1839, at age 30, Cornelius took a self-portrait outside of the family store. The daguerreotype produced is an off-center portrait of himself with crossed arms and tousled hair. While Louis Daguerre's photograph of the Boulevard du Temple, taken one year earlier, incidentally included two human figures on the sidewalk,[8][9] Cornelius' photo is the oldest known intentional photographic portrait of a human made in the United States.[10] It was preceded by at least some months by portraits taken by Hippolyte Bayard in France.[11] The quality of the photographic plate and the technique used required him to sit motionless for 10 to 15 minutes.

Cornelius would operate two of the earliest photographic studios in the United States between 1841 and 1843. His studio achieved improved photographic quality through the implementation of reflectors to direct additional light onto the portrait subject and blue glass filters. These changes along with improved photographic plates allowed portrait subject to only have to remain still for about one minute. His studio became popular with wealthy patrons and many of his portraits of famous people still exist.[12] As the popularity of photography grew and more photographers opened studios, Cornelius either lost interest or realized that he could make more money at the family gas and lighting company.[13]

He managed Cornelius & Co. (later known as Cornelius & Baker) and had great success with his invention of the "solar lamp". At the time, whale-oil was used in lamps but had become very expensive. Cornelius revised a British lamp design which forced additional air into the burner and allowed for the burning of lard rather than whale oil. He applied for and received a U.S. patent for the "solar lamp" in 1843. The lamp proved extremely popular and was sold in the U.S. and Europe. Two large factories in Philadelphia manufactured the lamp. Cornelius also received patents for lighting gaslights with electric sparks. The Cornelius lamp company also created the first kerosene lamp, however cheaper and more efficient versions dominated the market. While Cornelius was still a wealthy man, his once dominant lamp company was overtaken by other companies.[14]

Cornelius did not make much of his achievement of the first human photograph in the United States. It survived due to the efforts of Marcus Aurelius Root, a pupil at Cornelius' studio. Root published The Camera and The Pencil which provided background on the roots of photography in the United States. The book was highlighted at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and caught the attention of Julius Sachse, a noted Philadelphia photographer and future editor of American Journal of Photography. Sachse began interviewing Cornelius and other members of the American Philosophical Society in order to record the history of photography in the United States correctly. Cornelius told Sachse that he began taking photographs in October 1839 but no evidence was found of his claim until 1975 when a librarian at the American Philosophical Society discovered photographs taken by Cornelius dated in 1839.[7]

Personal life

Cornelius married Harriet Comly (sometimes spelled "Comely") in 1832. They had eight children: three sons and five daughters.[15]

Later years and death

Cornelius retired from his family's business in 1877.[16] In his later years, he lived at his country home in Frankford, Philadelphia. Cornelius was also an elder at the Presbyterian Church, where he was a member for fifty years.[17] He died at his Frankford home on August 10, 1893[16][18] and was interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery.[19]

Gallery

Examples of Cornelius' photographs:

-

Captain Charles John Biddle

-

Portrait of Martin Hans Boyè during chemical experiments

-

Martin Hans Boyè in 1841

-

Philadelphia 8th & Market Street in 1840

References

- ^ Meehan, Sean Ross (January 1, 2008). Mediating American Autobiography: Photography in Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass, and Whitman. University of Missouri Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8262-6640-8.

- ^ American Journal of Photography, Volume 14. Thos. H. McCollin & Company. 1893. p. 420.

- ^ Hannavy, John, ed. (2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1.

- ^ Cornelius, Ellanor Frances (1926). History of the Cornelius Family in America: Historical, Genealogical, Biographical; Containing a History of the Name from 212 B.C. and a Complete Genealogical Chart from 1639 to 1926, with Affiliated Families in Direct Line. Also Short Stories and Biographical Sketches and Illustrations. Grand Rapids, Mich., 1926. p. 37.

- ^ Barger, M. Susan & White, William B. (2000). The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science. JHU Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780801864582.

- ^ Johnson, Carol (2008). Hannavy, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. New York: Routledge. p. 339. ISBN 9781135873271.

- ^ a b "Robert Cornelius Historical Marker". www.explorepahistory.com. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Nicholas (October 26, 2010). "The First Photograph of a Human". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (November 5, 2014). "This is the first ever photograph of a human – and how the scene it was taken in looks today". The Independent. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Hannavy, John (December 16, 2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-135-87327-1.

- ^ Newhall, Beaumont (1937), Photography 1839–1937 : with an introduction by Beaumont Newhall, The Museum, p. 39, 102

- ^ Long, John Davis (1913). The American Business Encyclopaedia and Legal Advisor, Volume 4. Boston: J.B. Millet Co. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ Brin, Joseph G. "I'm Still Here: Saving the Work of Robert Cornelius". www.hiddencityphila.org. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Mattausch, Daniel (April 6, 2015). "A tour through storage brings an innovator to light". www.americanhistory.si.edu. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Hannavy 2013 p.340

- ^ a b American Journal of Photography. Thos. H. McCollin & Company. 1893. p. 420.

- ^ American Journal of Photography, Volume 14 1893 pp.420–422

- ^ Society, American Philosophical (1893). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. p. 242.

- ^ Wolgemuth, Rachel (2016). Cemetery Tours and Programming: A Guide. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 48. ISBN 9781442263178. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

External links

- 1809 births

- 1893 deaths

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- 19th-century American inventors

- 19th-century American photographers

- American patent holders

- American people of Dutch descent

- American Presbyterians

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- Businesspeople from Philadelphia

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Photographers from Philadelphia

- Pioneers of photography

- Selfies