Funj Sultanate

The Blue Sultanate / Funj Sultanate السلطنة الزرقاء Template:Ar icon As-Saltana az-Zarqa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1504–1821 | |||||||||

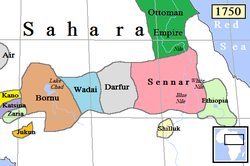

Sultanate of Sennar (in pink) and surrounding states in 1750 | |||||||||

| Status | Confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal chieftaincies under Sennar's suzerainty[1] | ||||||||

| Capital | Sennar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic[2] | ||||||||

| Religion | African Traditional Religion, Islam[3] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Mek (sultan) | |||||||||

• 1504–1533/4 | Amara Dunqas (first) | ||||||||

• 1805–1821 | Badi VII (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council[4] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Established | 1504 | ||||||||

• Conquered by Muhammad Ali's army | 14 June 1821 | ||||||||

| 13 February 1841 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1820 | 5,156,000[b] | ||||||||

| Currency | None (barter)[c] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

^ a. Muhammad Ali was granted the non-hereditary governorship of Sudan by an 1841 Ottoman firman.[5]

^ b. Estimate for entire area covered by modern Sudan.[6] ^ c. The Funj Sultanate did not mint coins and the markets did not use coinage as a form of exchange.[7] French surgeon J. C. Poncet, who visited Sennar in 1699, mentions the use of foreign coins such as Spanish reals.[8] | |||||||||

The Funj Sultanate of Sennar (sometimes spelled Sinnar; also known as the Funj Monarchy, Funj Caliphate or Funj Kingdom;[9] traditionally known in Sudan as the Blue Sultanate due to the Sudanese convention of referring to African peoples as blue ([السلطنة الزرقاء; As-Saltana az-Zarqa] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help))[10]) was a sultanate in the north of Sudan, named after the Funj ethnic group of its dynasty, or Sinnar (or Sennar) after its capital, which ruled a substantial area of northeast Africa between 1504 and 1821.

Origin

In the 15th century the part of Nubia previously controlled by Makuria was home to a number of small states and subject to frequent incursions by desert nomads. The situation in Alodia is less well known, but it also seems as though that state had collapsed. The area was reunified under Abdallah Jamma, the gatherer, who came from the eastern regions that had grown wealthy and powerful from the trade on the Red Sea. To him is ascribed the capture of Soba, which sank into unimportance: according to Reubeni, in the time of ‘Amara Dunqas it was in ruins. ‘Abdallah’s status as Muslim hero is confirmed by traditions representing him marrying the daughter of a Hijazi holy man called Alshikh Hamd Abou Dunana who was burned in Abu Delaig, and as the eponymous ancestor of the ruling clan, the ‘Abdallab.[11]

Abdallah's empire was short lived as in the early 16th century the Funj people under Amara Dunqas arrived from the south, having been driven north by the Shilluk. The Funj defeated the kingdom of Aiwa in 1504 and set up their own kingdom based at Sennar.[12][13] The new Funj kingdom reached from north to the third cataract, south to the foothills of Ethiopia, and east to the desert of Kordofan. Its rulers were Muslim and used Arabic as the lingua franca of trade. Although, the court was conducted all in Funj. Only in the 18th century did the court start using Arabic.[14]

The Funj Monarchy was a partrimonial regime built on a Sudanese concept of the semidivine kingship. The public appearance of sultans was accompanied by pomp and ceremony, but Funj rulers spent most of their reigns secluded from public view. The ruler was in principle absolite but was in practice very much under the sway his viziers, courtiers, and family. Provincial nobles lived in castles supported by their own slave retainers. Provincial nobles, however, had to appear before the sultan each year to perform obeisance, account for their behavoir, and deliver tribute. Each lesser lord was also required to take a wife from the royal family so that every vassal was related to the ruler. The ruling community formed a caste-like group that avoided intermarriage with the local population. The Funj sultanate reached its maximum power in the reign of Badi the 2nd (1644-1680).[15]

Religion

Islam had an important influence, and in 1523 the Sennar monarchy officially converted to Islam. Islam spread in the Funj sultanate not only as the result of its acceptance by the governing elite and the trading communities, but also as the result of the migration of Ulama and holy men into the region. In the 16th century Funj patronage attracted scholars from Egypt, North Africa, and Arabia. These holy men, known locally as faqis, were scholars of the Quran and Islamic Law and Sufi mystics. The Ulama had considerable influence, because they could intercede with and even rebuke the rulers, and because they were venerated by the common people for their miracles. Many Ulama were also merchants who founded lineages, settled in villages, established madrassahs, and won the populace over to Islam. Their zawiyas were residences and places of prayer in which the holy men lived surrounded by their families, servants, and disciples. Their schools Khalwas taught young boys the Quran, Islamic Law, and Islamic theology. In time the zawiyas grew into colonies and villages in which the descendants of the original holy men maintained a spiritual or temporal authority. They administered Maliki Law, arbitrated local disputes, and instructed the people in Islam. They were believed to possess barakah, the power given by God to perform miracles. The eastern Sudanic Ulama were also members of the Sufi brotherhoods. The Shadhiliya was brought into the Sudan in the 15th century, the Qadariyya in the middle 16th, and the Majdhubiyya in the 18th.[16]

Expansion and conflicts

Sennar expanded rapidly at the expense of neighboring states. Its power was extended over the Gezira, the Butana, the Bayuda, and southern Kordofan. This caused immediate tensions with its neighbours. Ethiopia felt it was much threatened but its internal problems prevented intervention. Newly Ottoman Egypt also saw the new state as a threat and invaded in force, but then failed to conquer the area, so the Ottoman forces fortified the border and consolidated their hold on northern Nubia. This border would hold until 1821.

Relations with Ethiopia were more strained as both states competed over lowlands between their two states. Eventually the Ethiopians moved their capital to nearby Gondar and secured their influence over these areas. Conflicts with the Shilluk to the south continued, but later the two were forced into an uneasy alliance to combat the growing might of the Dinka. Under Sultan Badi II, Sennar defeated the Kingdom of Taqali to the west and made its ruler (styled Woster or Makk) his vassal.

Military culture

The many armies of Sennar relied most on heavy cavalry: horsemen drawn from the nobility, armed with long broadswords as the toe stirrups they used did not permit the use of lances. These riders were armoured with chain mail while the horses were covered in thick quilts and copper headgear. A greater mass of troops were infantry carrying swords and who were also armoured. This permanent standing army, the largest in East Africa until the 1810s, was garrisoned in castles and forts throughout the sultanate. Reliance on a standing army meant that the professional armies fielded by Sennar were usually smaller, but highly effective against their less organized rivals.

The sultanate was heavily divided along geographic and racial/ethnic lines. The society was divided into six racial groups. There was a sharp division between those who were the heirs of the ancient kingdom of Alodia and the rest of Sennar. The Alodians adopted the mantle of the defeated Abdallah Jamma and came to be known as the Abdallab. In the late 16th century they rose in revolt under Ajib the Great. Ajib Alkafuta routed the kings of Sennar, first making them his vassals and then seizing almost the entire kingdom in 1606; the kings fled until they reached Abyssinia in the eastern region. The Sennar monarchy regrouped under Adlan I, defeating Ajib in a pair of decisive battles. Eventually a compromise was reached whereby Ajib and his successors would rule the Sennar province of Dongola with a great deal of autonomy.

One of the famous Abdallab leaders in 1798 was Alamin Musmar Wad Agib who defeated Hamaj in different battles. Besides his victory against Abyssinia, Alamin Musmar killed both Badi Abuelkilk and his cousin Rajab in different battles.[17]

Trade

The capital Sennar, prosperous through trade, hosted representatives from all over the Middle East and Africa. The wealth and power of the sultans had long rested on the control of the economy. All caravans were controlled by the monarch, as was the gold supply that functioned as the state's main currency. Important revenues came from customs dues levied on the caravan routers leading to Egypt and the Red Sea ports and on the pilgrimage traffic from the Western Sudan. In the late 17th century the Funj had opened up trading with the Ottoman Empire. In the late 17th century with the introduction of coinage, an unregulated market system took hold, and the sultans lost control of the market to a new merchant middle class. Foreign currencies became widely used by merchants breaking the power of the monarch to closely control the economy. The thriving trade created a wealthy class of educated and literate merchants, who read widely about Islam and became much concerned about the lack of orthodoxy in the kingdom. The monarchy of Sennar had long been regarded as semi-divine, in keeping with ancient traditions, but this idea ran strongly counter to Islam. Many festivals and rituals also persisted from earlier days, and a number them involved massive consumption of alcohol. These traditions were also abandoned. At the same time civil wars forced the peasants to look to the holy men for protection; the sultans lost the peasant population to the Ulama.[18]

The Sultanate also did their best to monopolize the slave trade to Egypt, most notably through the annual caravan of up to one thousand slaves. This monopoly was most successful in the seventeenth century, although it still worked to some extent in the eighteenth.[19]

Decline

Sennar was at its peak at the end of the 16th century, but during the 17th century it began to decline as the power of the monarchy was eroded. The greatest challenge to the authority of the king was the merchant funded ulema who insisted it was rightfully their duty to mete out justice.

In 1762, Badi IV was overthrown in a coup launched by Abu Likayik of the red Hamaj from the northeast of the country. Abu Likayik installed another member of the royal family as his puppet sultan and ruled as regent. This began a long conflict between the Funj sultans attempting to reassert their independence and authority and the Hamaj regents attempting to maintain control of the true power of the state.

These internal divisions greatly weakened the state and in the late 18th century Mek Adlan II, son of Mek Taifara, took power during a turbulent time at which a Turkish presence was being established in the Funj kingdom. The Turkish ruler, Al-Tahir Agha, married Khadeeja, daughter of Mek Adlan II. This paved the way for the assimilation of the Funj into the Ottoman Empire.

In 1821, Ismail bin Muhammad Ali, the general and son of the nominally Ottoman khedive of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, led an army into Sennar; he encountered no resistance from the last king, whose realm was promptly absorbed into "Ottoman" Egypt. The region was subsequently absorbed into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the independent Republic of Sudan on that country's independence in 1956.

The autonomy of the provincial vassals, merchant communities, and Ulama and their peasant clients subverted the power of the Funj sultanate. After a long and fitful history, the Funj kingdom disintegrated in the 18th century. The system of marriage alliances and princely hostages on which the power of the state depended on broke down; local dynasties became autonomous. The Funj kingdom was finally brought to an end by the Egyptian conquest. Muhammad Ali Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, established a government of Egyptian and Turkish officers based in the new city of Khartoum to exact tribute in slaves for the Egyptian army. The Egyptians created a counter-relgious elite to the indigineous Ulama by setting up a hierarchy of Qadis and Muftis and a new court system, and by educating young Sudanese scholars at al-Azhar in Cairo.[20]

Rulers

The rulers of Sennar held the title of Mek (sultan). Their regnal numbers vary from source to source.[21][22]

- Amara Dunqas 1503-1533/4 (AH 940)

- Nayil 1533/4 (AH 940)-1550/1 (AH 957)

- Abd al-Qadir I 1550/1 (AH 957)-1557/8 (AH 965)

- Abu Sakikin 1557/8 (AH 965)-1568

- Dakin 1568-1585/6 (AH 994)

- Dawra 1585/6 (AH 994)-1587/8 (AH 996)

- Tayyib 1587/8 (AH 996)-1591

- Unsa I 1591-1603/4 (AH 1012)

- Abd al-Qadir II 1603/4 (AH 1012)-1606

- Adlan I 1606-1611/2 (AH 1020)

- Badi I 1611/2 (AH 1020)-1616/7 (AH 1025)

- Rabat I 1616/7 (AH 1025)-1644/5

- Badi II 1644/5-1681

- Unsa II 1681–1692

- Badi III 1692–1716

- Unsa III 1719–1720

- Nul 1720–1724

- Badi IV 1724–1762

- Nasir 1762–1769

- Isma'il 1768–1776

- Adlan II 1776–1789

- Awkal 1787–1788

- Tayyib II 1788–1790

- Badi V 1790

- Nawwar 1790–1791

- Badi VI 1791–1798

- Ranfi 1798–1804

- Agban 1804–1805

- Badi VII 1805–1821

Hamaj regents

- Abu Likayik – 1769-1775/6

- Badi walad Rajab – 1775/6-1780

- Rajab 1780-1786/7

- Nasir 1786/7-1798

- Idris wad Abu Likayik – 1798–1804

- Adlan wad Abu Likayik – 1804–1805

See also

References

- ^ Ofcansky, Thomas (Research completed June 1991). Helen Chapin Metz (ed.). Sudan: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. The Funj.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan, 1500–1850. Series in Islam and Society in Africa. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8101-1069-4.

The spread of Arabic flowed not only from the dispersion of Arabs but from the unification of the Nile by a government, the Funj sultanate, that utilized Arabic as an official means of communication, and from the use of Arabic as a trade language.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer (1996). "Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa, till the 19th century". The Last Great Muslim Empires. History of the Muslim World, 3. Abbreviated and adapted by F. R. C. Bagley (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-55876-112-4.

The date when the Funj rulers adopted Islam is not known, but must have been fairly soon after the foundation of Sennār, because they then entered into relations with Muslim groups over a wide area.

- ^ Welch, Galbraith (1949). North African Prelude: The First Seven Thousand Years (snippet view). New York: W. Morrow. p. 463. OCLC 413248. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

The government was semirepublican; when a king died the great council picked a successor from among the royal children. Then—presumably to keep the peace—they killed all the rest.

- ^ فرمان سلطاني إلى محمد علي بتقليده حكم السودان بغير حق التوارث [Sultanic Firman to Muhammad Ali Appointing Him Ruler of the Sudan Without Hereditary Rights] (in Arabic). Bibliotheca Alexandrina: Memory of Modern Egypt Digital Archive. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Avakov, Alexander V. (2010). Two Thousand Years of Economic Statistics: World Population, GDP, and PPP. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87586-750-2.

- ^ Anderson, Julie R. (2008). "A Mamluk Coin from Kulubnarti, Sudan" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (10): 68. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

Much further to the south, the Funj Sultanate based in Sennar (1504/5–1820), did not mint coins and the markets did not normally use coinage as a form of exchange. Foreign coins themselves were commodities and frequently kept for jewellery. Units of items such as gold, grain, iron, cloth and salt had specific values and were used for trade, particularly on a national level.

- ^ Pinkerton, John (1814). "Poncet's Journey to Abyssinia". A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World. Vol. Volume 15. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. p. 71. OCLC 1397394.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014. pg 477-479

- ^ Ogot 1999, p. 91

- ^ catalogue.pearsoned.co.uk

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ Holt 1975, pp. 40–42

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ books.google.com

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul (2012). Transformations in Slavery: a History of Slavery in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ MacMichael, H. A. (1922). "Appendix I: The Chronology of the Fung Kings". A History of the Arabs in the Sudan and Some Account of the People Who Preceded Them and of the Tribes Inhabiting Dárfūr. Vol. Volume II. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. OCLC 264942362.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Holt, Peter Malcolm (1999). "Genealogical Tables and King-Lists". The Sudan of the Three Niles: The Funj Chronicle 910–1288 / 1504–1871. Islamic History and Civilization, 26. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 182–186. ISBN 978-90-04-11256-8.

Bibliography

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (1975). "Chapter 1: Egypt, the Funj and Darfur". In Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland (eds.). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. Volume 4: from c. 1600 to c. 1790. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ogot, B. A., ed. (1999). "Chapter 7: The Sudan, 1500–1800". General History of Africa. Vol. Volume V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 89–103. ISBN 978-0-520-06700-4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - R.S. O'Fahey and J.L Spaulding: Kingdoms of the Sudan Studies of African History Vol. 9, Methuen, London 1974, ISBN 0-416-77450-4

- Arthur E. Robinson, "Some Notes on the Regalia of the Fung Sultans of Sennar", Journal of the Royal African Society, 30 (1931), pp. 361–376