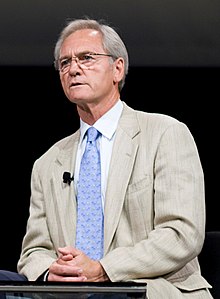

Don Siegelman

Don Siegelman | |

|---|---|

| |

| 51st Governor of Alabama | |

| In office January 18, 1999 – January 20, 2003 | |

| Lieutenant | Steve Windom |

| Preceded by | Fob James |

| Succeeded by | Bob Riley |

| 26th Lieutenant Governor of Alabama | |

| In office January 16, 1995 – January 18, 1999 | |

| Governor | Fob James |

| Preceded by | Jim Folsom |

| Succeeded by | Steve Windom |

| 43rd Attorney General of Alabama | |

| In office January 19, 1987 – January 21, 1991 | |

| Governor | Guy Hunt |

| Preceded by | Charles Graddick |

| Succeeded by | Jimmy Evans |

| 44th Secretary of State of Alabama | |

| In office January 15, 1979 – January 17, 1987 | |

| Governor | Fob James George Wallace |

| Preceded by | Agnes Baggett |

| Succeeded by | Glen Browder |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Donald Eugene Siegelman February 24, 1946 Mobile, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Lori Allen (m. 1980) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | University of Alabama (BA) Georgetown University (JD) Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1968–1969 |

| Unit | Air National Guard |

Donald Eugene Siegelman (/ˈsiːɡəlmən/ SEE-gəl-mən; born February 24, 1946) is an American politician who was the 51st governor of Alabama from 1999 to 2003. As of 2024, Siegelman is the last Democrat as well as the only Catholic to serve as Governor of Alabama .

Siegelman is the only person in Alabama's history to be elected to serve in all four of the top statewide elected offices: Secretary of State, Attorney General, Lieutenant Governor, and Governor. He served in Alabama politics for 26 years.[1]

In 2006, Siegelman was convicted on federal felony corruption charges and sentenced to seven years in federal prison.[1][2] Following the trial, however, many questions were raised by both Democrats and Republicans about allegations of prosecutorial misconduct in his case.[3][4][5] On March 6, 2009, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld key bribery, conspiracy, and obstruction counts against Siegelman and refused his request for a new trial.[citation needed]

In October 2015, more than 100 former attorneys general and officials, both Democratic and Republican, contended that his prosecution was marred by prosecutorial misconduct; they have petitioned the United States Supreme Court to review the case.[6] Siegelman was released from prison on February 8, 2017, and was on supervised probation until June 2019.[7][8]

Personal life and early career

[edit]Siegelman was born and raised in Mobile, Alabama, the son of Catherine Andrea (née Schottgen) and Leslie Bouchet Siegelman,[9] and raised in the Catholic faith.

He earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Alabama, where he was a brother of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Psi chapter), in 1968. Siegelman served in the Air National Guard for 19 months as a fuel handler and fuel truck driver, and was discharged for medical reasons in 1969.[10] In his 1994 campaign for lieutenant governor, Republican Charles Graddick argued that Siegelman had been discharged as the result of mental health issues.[11] Siegelman stated that he had received an honorable discharge as the result of several physical symptoms including high blood pressure, high pulse rate, headaches, and dizziness that were attributed to stress over family concerns including the illness of his father.[10]

He earned a J.D. degree from Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, D.C., in 1972. He studied international law at Pembroke College, Oxford from 1972 to 1973.[12][13]

While at the University of Alabama, Siegelman served as the president of the student government association. While in law school, Siegelman worked as an officer in the United States Capitol Police to support himself.

Siegelman married Lori Allen, and they have two children, Dana and Joseph. His wife is Jewish and they reared their children in the Jewish faith.[14]

His son, Joseph, was the Democratic nominee for Attorney General of Alabama in the 2018 election, losing to incumbent Steve Marshall.[15]

Political career

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

After college and graduate school, Siegelman became active in the Democratic Party in Alabama. In 1978, he was elected Secretary of State of Alabama. He served two terms as Secretary of State, from 1979 to 1987.

He was elected as Alabama's Attorney General in 1986, serving from 1987 to 1991. He ran for Governor in 1990 but lost in the Democratic primary runoff to Paul Hubbert, the executive secretary of the Alabama Education Association. Siegelman was elected as Lieutenant Governor in 1994, serving from 1995 to 1999.

In 1998, Siegelman was elected Governor with 57% of the vote, including more than 90% of the African American electorate.[citation needed] He was the first native Mobilian to be elected to the state's highest office. By that time, following passage by Congress in the mid-1960s of civil rights legislation, most African Americans in the South supported Democratic Party statewide and national candidates.

In 1988 as state Attorney General, Siegelman addressed the Alabama Chemical Association and met with Monsanto lobbyists. The state gave permission for Monsanto to direct their own cleanup of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) at their plant in Anniston, Alabama. The waterways of the town had been polluted by PCBs from the plant. This work has been strongly criticized as inadequate. For instance, Monsanto dredged PCBs from just a few hundred yards of Snow Creek and its tributaries.[16]

Governorship

[edit]Siegelman's term as Governor took place during, and contributed to, the dramatic growth in Alabama's automotive manufacturing industry. Mercedes-Benz had built the first new major automotive plant during the administration of Governor Jim Folsom Jr. During Siegelman's administration, Mercedes agreed to double the size of that plant.[citation needed]

Siegelman worked to recruit other manufacturers, visiting several countries and securing commitments from Toyota, Honda,[17] and Hyundai[18][19] to build major assembly plants in Alabama.

Siegelman presided over eight executions (seven by electric chair, one by lethal injection), including that of Lynda Lyon Block, the first female executed in the state since 1957. He also oversaw the transition from electrocution as a sole method to lethal injection as the primary method.

State lottery and universal education

[edit]Siegelman had campaigned for voter approval of a state lottery. The proceeds were to be earmarked to fund free tuition at state universities for most high school graduates. Siegelman supported a bill that placed the lottery on a free-standing referendum ballot in 1999. The measure was defeated.[20] Some advisors had suggested that Siegelman wait until the regular 2000 elections, when anti-gambling interests would command a smaller percentage of the electorate.[citation needed]

After the defeat of the lottery, Siegelman struggled to deal with serious state budget problems. Alabama's tax revenues were down during most of his administration. Observers believed that Siegelman did a decent job of managing the limited revenue produced by this system during a national economic downturn.[citation needed]

Siegelman launched the "Alabama Reading Initiative", an early education literacy program that was praised by both Democratic and Republican officials. It has been emulated by several other states.[citation needed]

2002 election controversy

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

U.S. Representative Bob Riley defeated Siegelman in his November 2002 reelection bid by the narrowest margin in Alabama history: approximately 3,000 votes.

On the night of the election, Siegelman was initially declared the winner by the Associated Press. Later, a voting machine malfunction in Baldwin County was claimed to have produced the votes needed to give Riley the election.

Democratic Party officials objected, stating that the recount had been performed by local Republican election officials after Democratic observers had left the site of the vote counting. This rendered verification of the recount results impossible. The state's Attorney General, Republican Bill Pryor, affirmed the recounted vote totals, securing Riley's election. Pryor denied requests for a manual recount of the disputed vote; he warned that opening the sealed votes to recount them would be held a criminal offense.[21]

Analysts said that perhaps the most objective observation about this purported vote shift was that there was no corresponding vote shift in other issues and candidates on these same ballots, a shift that would be expected if they were anti-Siegelman voters. Largely as a result of this obvious inconsistency, the Alabama Legislature amended the election code to provide for automatic, supervised recounts in close races.[22]

2006 election

[edit]Siegelman ran to become the Democratic nominee for the 2006 Alabama gubernatorial election; however, he was defeated in the primary by Lt. Governor Lucy Baxley, former wife of the controversial 1986 gubernatorial nominee, former attorney general and lieutenant governor Bill Baxley. In large part because of Siegelman's indictment for bribery and racketeering, Baxley was able to secure important endorsements from the Alabama Democratic Conference, the New South Coalition, and the Alabama State Employees Association. Although outspent by Siegelman, and criticized on her call for a raise of the state's minimum wage by $1, Baxley coasted to a relatively easy primary win of 60% to Siegelman's 36%. She lost the general election for governor later that year to Republican Bob Riley, 42-58 percent.[citation needed]

Federal prosecution

[edit]2004 trial

[edit]On May 27, 2004, Siegelman was indicted by the federal government for fraud. The day after his trial began in October 2004, prosecutors dropped all charges after U.S. District Judge U. W. Clemon had thrown out much of the prosecution's evidence, stating that no new charges could be refiled based on the disallowed evidence.[23]

2006 conviction

[edit]On October 26, 2005, Siegelman was indicted on new charges of bribery and mail fraud in connection with Richard M. Scrushy, founder and former CEO of HealthSouth. Two former Siegelman aides were charged in the indictment as well. Siegelman was accused of trading government favors for campaign donations as Lieutenant Governor from 1995 to 1999, and as Governor from 1999 to 2003.

Scrushy was accused of arranging $500,000 in donations to Siegelman's 1999 campaign for a state lottery fund for universal education, in exchange for a seat on a state hospital regulatory board, a non-paying position. Scrushy had been appointed and served on the state hospital regulatory board during the past three Republican administrations. He had been acquitted in 2005 of charges of securities fraud for his part in the HealthSouth Corporation fraud scandal which cost shareholders billions.[24]

During his trial, Siegelman continued his campaign for reelection, running in the Democratic primary against Lt. Governor Lucy Baxley and minor candidates. On June 6, despite Baxley's relatively low-profile campaign, she defeated Siegelman with almost 60% of the vote compared to Siegelman's 36%.[25]

On June 29, 2006, three weeks after Siegelman lost the primary, a federal jury found both Siegelman and Scrushy guilty on seven of the 33 felony counts in the indictment. Two co-defendants, Siegelman's former chief of staff, Paul Hamrick and his transportation director, Mack Roberts, were acquitted of all charges. Siegelman was convicted on one count of bribery, one count of conspiracy to commit honest services mail fraud, four counts of honest services mail fraud, and one count of obstruction of justice.[26]

Siegelman was acquitted on 25 counts, including the indictment's allegations of a widespread RICO conspiracy.[27] Siegelman was represented by Mobile attorneys Vince Kilborn and David McDonald, along with Greenwood attorney Hiram Eastland and Notre Dame law professor G. Robert Blakey, an authority on RICO. Siegelman was sentenced by Judge Mark Everett Fuller, a George W. Bush appointee, to more than seven years in federal prison and a $50,000 fine.[2]

Siegelman said in his defense that Scrushy had been on the regulatory board of the state hospital during several preceding Republican governorships. He said that Scrushy's contribution toward the campaign for a state lottery fund for universal education was unrelated to his appointment. Siegelman and his attorneys said that the charges against him, in addition to being unfounded, were without precedent.[2]

Scrushy was released from federal prison in April 2012. He resided in a Houston, Texas halfway house until he was released on July 25, 2012.[28][29]

Release from federal prison

[edit]

On Thursday, March 27, 2008, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals approved Siegelman's release from federal prison while he appealed his conviction in the corruption case. He was released the following day.[30] The federal court approved the release of Siegelman on bail.[31]

Siegelman told the Democratic National Committee that he believed Karl Rove should be held in contempt for refusing to testify before the House committee that investigated Siegelman's conviction.[32] No action against Rove was taken.

2009 appeal

[edit]On March 6, 2009, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld key bribery, conspiracy and obstruction counts against Siegelman and refused his request for a new trial. It found no evidence that the conviction was unjust. However, the Court struck down two of the seven charges on which Siegelman was convicted and ordered a new sentencing hearing.[33] His sentence was reduced by 10 months, leaving him with 69 months.[34]

2014 appeal

[edit]After several delays requested by Siegelman, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals heard Siegelman's appeal for a new trial in May 2015. Arguments had originally been expected in October 2014.[35][36] The Court upheld the decision of a lower court to deny appeal.[37]

Appeal issues

[edit]Witness Nick Bailey, who provided the cornerstone testimony upon which the conviction was based, was subsequently convicted of extortion. Facing 10 years in prison, Bailey had cooperated with prosecutors to lighten his own sentence. Although he engaged in more than 70 interviews with the prosecution against Siegelman, none of the notes detailing these interviews was shared with the defense. In addition, after the case was tried, it was confirmed that the check which Bailey testified to seeing Scrushy write for Siegelman, was written days later, when he was not present.[38][39]

Juror partiality

[edit]Documents indicated that prosecutors interviewed two jurors while the court was reviewing charges of juror misconduct.[citation needed] This was in violation of the judge's instruction that no contact with jurors should occur without his permission.[citation needed]

Karl Rove connection

[edit]There were allegations that Siegelman's prosecution was politically motivated. Purportedly, Bush-appointed officials at the Justice Department had pressed for the prosecution, as did Leura Canary, a U.S. Attorney in Montgomery, Alabama. Her husband was Alabama's top Republican operative and he had for years worked closely with Karl Rove, part of the George W. Bush White House staff.

In June 2006, a Republican lawyer, Dana Jill Simpson of Rainsville, Alabama, signed an affidavit, claiming that, five years earlier, she had heard that Rove was preparing to neutralize Siegelman politically with an investigation headed by the U.S. Department of Justice.[40]

Simpson later told The Birmingham News that her affidavit's wording could be interpreted in two ways. She said she had written her affidavit herself. But, in testimony before a Congressional committee on this case, she said that she had help on it from a Siegelman supporter.[41]

According to Simpson's statement, she was on a Republican campaign conference call in 2002 when she heard Bill Canary tell other campaign workers not to worry about Siegelman. He said that Canary's "girls" and "Karl" would make sure the Justice Department pursued the Democrat so he was not a political threat in the future.[40]

"Canary's girls" supposedly included his wife, Leaura Canary, US Attorney for the Middle District of Alabama, and Alice Martin, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama.[40] Leaura Canary did not submit voluntary recusal paperwork until two months after Siegelman attorney David Cromwell Johnson's press conference in March 2002, at which he criticized her participation because of her husband's political role.[42][43]

In interviews with the press, Simpson has reiterated that she heard Rove's name mentioned in a phone conversation in which the discussion turned to Siegelman. She clarified that she heard someone involved in a 2002 conference call refer to a meeting between Rove and Justice Department officials on the subject of Siegelman, and revealed that Rove directed her to "catch Siegelman cheating on his wife".[38]

Raw Story reported in 2007 that Rove had advised Bill Canary on managing Republican Bob Riley's gubernatorial campaign against Siegelman, including during the election fraud controversy of 2002. This was based on the testimony of "two Republican lawyers who have asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation", one of whom is close to Alabama's Republican National Committee.[44]

Simpson's house burned down soon after she began to speak out about the Siegelman case. She claimed her car was forced off the road by a private investigator and wrecked but police investigations of the fire and the wreck found no evidence of foul play. Simpson said, "Anytime you speak truth to power, there are great risks. I've been attacked."[45] She told a reporter for The Nation that she felt a "moral obligation" to speak up.[45]

Alleged misconduct by attorney general

[edit]In November 2008, new documents revealed alleged misconduct by the Bush-appointed U.S. attorney and other prosecutors in the Siegelman/Scrushy case. There were allegations that extensive and unusual contact occurred between the prosecution and the jury.[31] According to Time, a Department of Justice staffer furnished the new documents at the risk of losing her job. The documents included e-mails written by Leura Canary, long after her recusal, offering legal advice to subordinates handling the case. At the time Canary wrote the e-mails, her husband was publicly supporting the state's Republican governor, Bob Riley. In one of Leura Canary's e-mails made public by Time, dated September 19, 2005, she forwarded senior prosecutors on the Siegelman case a three-page political commentary by Siegelman.

Canary highlighted a single passage, telling her subordinates,

Y'all need to read, because he refers to a 'survey' which allegedly shows that 67% of Alabamians believe the investigation of him to be politically motivated ... Perhaps [this is] grounds not to let [Siegelman] discuss court activities in the media!

At Siegelman's sentencing, the prosecutors urged the judge to use these public statements by Siegelman as grounds for increasing his prison sentence.[31]

Public reaction

[edit]In July 2007, 44 former state attorneys general, both Democrats and Republicans, filed a petition to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees requesting further investigation of the Siegelman prosecution.[46][47]

On July 17, 2007, House Judiciary Committee Chairman John Conyers (D, MI-14) and Reps. Linda Sánchez (D, CA-39), Artur Davis (D, AL-07), and Tammy Baldwin (D, WI-02) sent a letter to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, asking him to provide documents and information about former Alabama Democratic Governor Don Siegelman's recent conviction, among others, that may have been part of a pattern of selective political prosecutions by a number of U.S. Attorneys across the country. The deadline for the Attorney General's office to provide the information to Congress was July 27, 2007. The documents had not been produced by August 28, 2007, when Gonzales announced that he would resign.[48] In an editorial that day, The New York Times said that despite Gonzales' departure, "[M]any questions remain to be answered. High on the list: what role politics played in dubious prosecutions, like those of former Gov. Don Siegelman of Alabama, and Georgia Thompson, a Wisconsin civil servant."[49] Press reports have suggested that perhaps U.S. Attorney Leura Canary did not follow proper Department of Justice procedures in recusing herself from the Siegelman matter. There were no court filings to that effect and DOJ refused to disclose her recusal form under a Freedom of Information Act inquiry.[50]

On October 10, 2007, the House Judiciary Committee released testimony in which Dana Jill Simpson alleged that Karl Rove "had spoken with the Department of Justice" about "pursuing" Siegelman with help from two of Alabama's U.S. attorneys, and that Governor Bob Riley had named the judge who was eventually assigned to the case. She also claimed that Riley told her the judge would "hang Don Siegelman." In contrast with what she told 60 Minutes, in her sworn testimony before Congress, she never mentioned having met or spoken with Rove.[51][52]

Wider public

[edit]Siegelman defenders note that more than 100 federal charges were thrown out by three different judges. Further, they argue that there was an obvious conflict of interest in the prosecution against Siegelman, since the investigating U.S. Attorney was married to the campaign manager of his political opponent in the 2002 gubernatorial campaign.[40] Siegelman defenders argue that the sentence is unprecedented and the punishment excessive. By contrast, former Alabama Governor H. Guy Hunt, a Republican, was found guilty in state court of personally pocketing $200,000. State prosecutors sought probation, not jail time, in the Hunt case.[40]

Federal Communications Commission investigation

[edit]60 Minutes aired an investigative segment on the case, "The Prosecution of Governor Siegelman", on February 24, 2008.[53]

During the broadcast, CBS affiliate WHNT-TV in Huntsville, Alabama, did not air this segment of the program, claiming technical issues with the signal.[54]

Journalist and attorney Scott Horton of Harper's Magazine has stated that he contacted CBS News in New York regarding the issue. He said that representatives there said there were no transmission issues, and that WHNT had functioning transmitters at the time.[4]

Horton accused WHNT of a history of political hostility toward Siegelman. The station responded to the controversy by rebroadcasting the report later that night, and again the next day.[55]

In March 2008, the Federal Communications Commission began an investigation into why the north Alabama television station went dark during the February 24, 2008 broadcast of the "60 Minutes" installment.[56] The investigation resulted in no action.

Sentencing

[edit]On August 3, 2012, Siegelman was sentenced to more than six years in prison, a $50,000 fine, and 500 hours of community service. Siegelman was credited with time served, leaving 5 years, nine months remaining in his sentence. His daughter, Dana, initiated an online petition requesting a presidential pardon for Siegelman. At the re-sentencing, the judge told Siegelman that he did not hold this against him personally and wished him well with his sentence. The judge gave Siegelman until September 11 to report to prison. Richard Scrushy had not been released on bail, and has since served all his time.

Siegelman was released from prison on supervised probation on February 8, 2017.[57]

In popular culture

[edit]Siegelman's case was the subject of a 2017 documentary entitled Atticus v. The Architect: The Political Assassination of Don Siegelman, written and directed by Steve Wimberly.[58][59]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Faulk, Kent (February 8, 2017). "Timeline of Don Siegelman Case". AL.com. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Ex-governor of Alabama Gets 7 Years in Corruption Case", Los Angeles Times, June 29, 2007, p. A15 Archived October 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Did Ex-Alabama Governor Get A Raw Deal? 60 Minutes Reports On Bribery Conviction Of Don Siegelman In A Case Criticized by Democrats And Republicans", CBS News, February 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Horton, Scott (February 24, 2008). "CBS: More Prosecutorial Misconduct in Siegelman case". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Kent Faulk (May 18, 2019). "Timeline of Don Siegelman case". al.com.

- ^ "More than 100 former attorneys general ask US Supreme Court to review Siegelman sentence", Alabama Local News, October 22, 2015.

- ^ WSFA Staff (June 13, 2019). "Former Ala. Gov. Don Siegelman's probation officially ends".

- ^ Posted 8:03 am, June 14, 2019, by Associated Press (June 14, 2019). "Probation ends for former Alabama governor". WHNT.com. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Alabama Official and Statistical Register - Alabama. Dept. of Archives and History - Google Books. 1979. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Curran, Eddie (2009). The Governor of Goat Hill. New York, NY: iUniverse, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4401-8939-5.

- ^ Rawls, Phillip (November 4, 1994). "Graddick: Siegelman Records Show Psychiatric Illness". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, FL. Associated Press. p. 11A – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "How the World Changed After 9/11 - Speaker List". Howtheworldchanged.org. May 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ https://issuu.com/pembrokecollegeoxford/docs/pcr_1997-1998compressed [bare URL]

- ^ "Don Siegelman on the Issues". Ontheissues.org. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Joseph Siegelman, son of ex-governor, running for AG". al. February 9, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ Grunwald, Michael (August 21, 2012). "Monsanto Hid Decades Of Pollution PCBs Drenched Ala. Town, But No One Was Ever Told". Washington Post. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ "Honda Announces Major Plant Expansion," Talladega Daily Home, 10 July 2002

- ^ "Hyundai Announcement Ends Long Fight," The Montgomery Advertiser, 02 April 2002, p. A1

- ^ "Hyundai News". Hyundai News. Archived from the original on March 15, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Voters Say No, Now What?". Birmingham Post-Herald. October 14, 1999. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "The Changing of the Guards: Bay Minette, Election Night". Baldwincountynow.com. July 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ "Alabama Code § 17-16-20". Alisondb.legislature.state.al.us. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Siegelman Fraud Case Dismissed", The Huntsville Times, October 9, 2004, pg. 1A.

- ^ "HealthSouth to Settle S.E.C. Charges; Scrushy Jury Pauses" The New York Times, 09 June 2005, p. C3

- ^ "Alabama Secretary of State: 2006 Democratic Primary Certification" (PDF). Sos.state.al.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Department of Justice press release". Usdoj.gov. June 29, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Jury Convicts HealthSouth Founder in Bribery Trial". The Washington Post. June 29, 2006. p. D1. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Lyman, Brian (July 26, 2012). "Scrushy released from custody". Montgomery Advertiser. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- ^ Hutchens, Aaron (July 26, 2012). "Richard Scrushy released from federal custody". Alabama's 13. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ "Freed Ex-Governor of Alabama Talks of Abuse of Power", The New York Times, March 29, 2008, pg. A13

- ^ a b c Zagorin, Adam (November 14, 2008). "More Allegations of Misconduct in Alabama Governor Case". Time. Archived from the original on November 24, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Siegelman Pleads His Case At DNC". Wkrg.com. Associated Press. August 25, 2008. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Around the Nation". The Washington Post. March 7, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Don Siegelman returns to prison Tuesday". The Birmingham News. September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Chandler, Kim (August 28, 2013). "Former Gov. Don Siegelman seeks new trial". AL.com.

- ^ "Siegelman's Appeal Set for October". WTOK-TV. July 24, 2014. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, versus DON EUGENE SIEGELMAN, Defendant-Appellant" (PDF). Media.ca11.uscourts.gov. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Did Ex-Alabama Governor get a Raw Deal?". 60 Minutes. Cbsnews.com. February 24, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Adam Zagorin, "Selective Justice in Alabama?"; Time, October 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Ex-governor says he was target of Republican plot - Los Angeles Times". Archive.is. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Sims, Bob (October 12, 2007). "In her own words: Jill Simpson interview excerpts". The Birmingham News. Blog.al.com. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Siegelman Lawyer Says US Attorney Should Recuse Herself", The Bulletin's Frontrunner, March 26, 2002.

- ^ "Riley Denies Siegelman Case Claims", The Birmingham News, May 5, 2006, pg. 1B

- ^ Larisa Alexandrovna and Muriel Kane. "The Permanent Republican Majority: Part III – Running elections from the White House" Archived January 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The Raw Story, 2007.

- ^ a b Wilson, Glynn (October 24, 2007). "A Whistleblower's Tale". The Nation. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Text of petition, including names of signers, at Don Siegelman website

- ^ "Introductory letter" (PDF). Donsiegelman.net. July 13, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ "Government Blog". Speaker.gov. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Editorial (August 28, 2007): "The House Lawyer Departs" The New York Times, p. A20

- ^ Horton, Scott (September 14, 2007). "The Remarkable 'Recusal' of Leura Canary". Harper's Magazine. Harpers.org. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Zagorin, Adam (October 10, 2007). "Rove Linked to Alabama Case". Time. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Interview of Dana Jill Simpson Archived October 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, September 1, 2007

- ^ "The Prosecution Of Governor Siegelman". 60 Minutes. CBS News. February 24, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "60 Minutes Programming Note," WHNT-TV, February 24, 2008 Archived November 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Triplett, William (March 4, 2008). "FCC questions '60 Minutes' blackout". Variety. p. 6. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "‘60 Minutes’ Blackout Investigation" Archived October 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine AP March 4, 2008

- ^ JAMES, ANDREW (February 8, 2017). "Former Governor Don Siegelman Released from Federal Prison". Alabama News. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Wimberly profile, imdb.com. Accessed August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Atticus V. The Architect : The Political Assassination of Don Siegalman". AL.com. May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (April 2016) |

- DonSiegelman.org A website in support of Don Siegelman

- Alabama Department of Archives & History – Alabama Governor Don Siegelman profile

- National Governors Association – Alabama Governor Don Siegelman profile

- On the Issues – Don Siegelman issue positions and quotes

- Follow the Money – Don Siegelman

- The New York Times – Topics: Donald Siegelman collection of news stories

- locustfork.net: The first interview with Jill Simpson

- The Nation: A Whistleblower's Tale

- Siegelman archive, Harper's Scott Horton's ongoing investigation

- The New York Times – "Strange Case of An Imprisoned Alabama Governor" September 10, 2007

- Caylor, John "The Dixie Mafia's Contract on America" Archived February 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- The Raw Story – "The permanent Republican majority:Part One: How a coterie of Republican heavyweights sent a governor to jail" Archived December 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine November 26, 2007

- The Raw Story – "The permanent Republican majority:Part Two: Daughter of jailed governor sees White House hand in her father's fall" Archived January 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine November 27, 2007

- The Raw Story – "The permanent Republican majority:Part Three: Running elections from the White House" Archived January 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine December 16, 2007

- CBS News 60 Minutes – GOP Operative: Rove Sought To Smear Dem February 21, 2008

- Harper's Magazine – "More Prosecutorial Misconduct in Siegelman Case"

- Video of Karl Rove holding "Free Don Siegelman" banner February 25, 2008

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1946 births

- Alabama attorneys general

- Alabama politicians convicted of crimes

- American police officers convicted of obstruction of justice

- Catholics from Alabama

- Democratic Party governors of Alabama

- Georgetown University Law Center alumni

- Lawyers from Mobile, Alabama

- Lieutenant governors of Alabama

- Living people

- Politicians from Mobile, Alabama

- People from Vestavia Hills, Alabama

- Politicians convicted of honest services fraud

- Politicians convicted of program bribery

- Secretaries of state of Alabama

- United States Capitol Police officers

- University of Alabama alumni

- 20th-century Alabama politicians