Slug

| Slug | |

|---|---|

| |

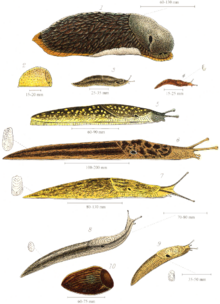

| Various species of British land slugs, including (from the top) the larger drawings: Arion ater, Kerry slug, Limax maximus and Limax flavus | |

| |

| Arion sp., Vancouver | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Groups included | |

| |

Slug is a common name that is normally applied to any gastropod mollusc that lacks a shell, that has a very reduced shell, or has a small internal shell. (This is in contrast to the common name snail, applied to gastropods that have a coiled shell large enough that the soft parts of the animal can retract fully into it.)

Slugs belong to several different lineages which also include snails that have shells. The various families of land slugs are not very closely related, despite a superficial similarity in the overall body form. The shell-less condition has arisen many times independently during the evolutionary past, and thus the category "slug" is emphatically a polyphyletic one.

As well as land slugs, there are also many marine slugs and even one freshwater slug genus (Acochlidium), but the common name "slug" is most frequently applied to air-breathing land slugs, while the marine forms are usually known as sea slugs. Land gastropods with a shell that is not quite vestigial, but is too small to retract into (like many in the family Urocyclidae), are known as semislugs.

Slugs, like all other gastropods, undergo torsion (a 180° twisting of the internal organs) during development. Internally, slug anatomy clearly shows the effects of this rotation, but externally the bodies of slugs appear rather symmetrical, except for the positioning of the pneumostome, which is on one side of the animal, normally the right hand side.

The soft, slimy bodies of slugs are prone to desiccation, so land-living slugs are confined to moist environments and must retreat to damp hiding places when the weather is dry.

Morphology and behavior

Like other pulmonate land snails, most slugs have two pairs of 'feelers' or tentacles on their head. The upper pair is light sensing and has eyespots at the ends, while the lower pair provides the sense of smell. Both pairs are retractable, and can be regrown if lost.

On top of the slug, behind the head, is the saddle-shaped mantle, and under this are the genital opening and anus. On one side (almost always the right hand side) of the mantle is a respiratory opening, which is easy to see when open, but difficult to see when closed. This opening is known as the pneumostome. Within the mantle in some species is a very small, rather flat shell.

Like other snails, a slug moves by rhythmic waves of muscular contraction on the underside of its foot. It simultaneously secretes a layer of mucus on which it travels, which helps prevent damage to the foot tissues. Around the edge of the foot is the 'foot fringe'.

Some slug species hibernate underground during the winter in temperate climates, but in other species, the adults die in the autumn.

Vestigial shell

Most slugs retain a remnant of their shell, which is usually internalized. This organ generally serves as storage for calcium salts, often in conjunction with the digestive glands.[2]

An internal shell is present in the Limacidae[3] and Parmacellidae.[4]

Adult Philomycidae,[3] Onchidiidae[5] and Veronicellidae[6] lack shells.

Mucus

Slugs' bodies are made up mostly of water, and without a full-sized shell, their soft tissues are prone to desiccation. They must generate protective mucus to survive. Many species are most active just after rain because of the moist ground. In drier conditions, they hide in damp places such as under tree bark, fallen logs, rocks, and man-made structures, such as planters, to help retain body moisture.

Slugs produce two types of mucus: one which is thin and watery, and another which is thick and sticky. Both kinds of mucus are hygroscopic. The thin mucus spreads from the foot's centre to its edges, whereas the thick mucus spreads from front to back. Slugs also produce thick mucus which coats the whole body of the animal.

The mucus secreted by the foot contains fibres which help prevent the slug from slipping down vertical surfaces. The "slime trail" that a slug leaves behind has some secondary effects: other slugs coming across a slime trail can recognize the slime trail as produced by one of the same species, which is useful in finding a mate. Following a slime trail is also part of the hunting behavior of some carnivorous slugs.

Body mucus provides some protection against predators, as it can make the slug hard to pick up and hold by a bird's beak, for example, and the mucus itself can be distasteful.

Some species of slug secrete slime cords to lower themselves onto the ground, or to suspend a pair of slugs during copulation.

Reproduction

Slugs are hermaphrodites, having both female and male reproductive organs.

Once a slug has located a mate, they encircle each other and sperm is exchanged through their protruded genitalia. A few days later the slugs lay around 30 eggs in a hole in the ground, or beneath the cover of an object such as a fallen log.

Apophallation is a commonly seen practice among many slugs. In apophallating species, the penis curls like a corkscrew and during mating often becomes entangled in the mate's genitalia. Apophallation allows the slugs to separate themselves by one or both of the slugs chewing off the other's penis. Once its penis has been removed, the slug is still able to mate using only the female parts of its reproductive system.

Ecology

Many slug species play an important ecosystem role by eating dead leaves, fungus, and decaying vegetable material. Other species eat parts of living plants.

Some slugs are predators and eat other slugs and snails, or earthworms.

Most carnivorous slugs on occasion also eat carrion, including dead of their own kind.

Predators

Frogs, toads, snakes, hedgehogs, salamanders, eastern box turtles, rats, caecilians and also some birds and beetles are slug predators. Slugs can be a vector of transmission of parasitic nematodes that cause lungworm in various mammals, so are usually avoided by hedgehogs and other mammals when other food is available.[citation needed]

Slugs, when attacked, can contract their body, making themselves harder and more compact, and combined with the slippery mucus is more difficult for many animals to grasp. The unpleasant taste of the mucus is also a deterrent.

Some slugs can self-amputate (autotomy) a portion of their tail to help the slug escape from a predator.[7]

Human relevance

The great majority of slug species are harmless to humans and to their interests, but a small number of species are serious pests of agriculture and horticulture. They can destroy foliage faster than plants can grow, thus killing even fairly large plants. They also feed on fruits and vegetables prior to harvest, making holes in the crop, which can make individual items unsuitable to sell for aesthetic reasons, and which can make the crop more vulnerable to rot and disease.

As control measures, baits are the norm in both agriculture and the garden. In recent years iron phosphate baits have emerged and are preferred over the toxic metaldehyde, especially because domestic or wild animals may be exposed to the bait. The environmentally safer iron phosphate has been shown to be at least as effective as poisonous baits.[8] Methiocarb baits are no longer widely used.

Beneficial nematodes (Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita) are a commercially available biological control method that are effective against a wide range of common slug species. The nematodes are applied in water and actively seek out slugs in the soil and infect them, leading to the death of the slug. This control method is suitable for use in organic growing systems.

Other slug control methods are generally ineffective, but can be somewhat useful in small gardens. These include beer traps,[9] diatomaceous earth, crushed eggshells, coffee grounds, and copper.

It is of scientific interest that salt kills slugs by causing water to leave its body owing to osmosis [10] but this is not used for agricultural control as soil salinity is detrimental to crops.

In a few rare cases, humans have contracted parasite-induced meningitis from eating raw slugs.[11]

In rural southern Italy, the garden slug Arion hortensis was used to treat gastritis, stomach ulcers or peptic ulcers by swallowing it whole and alive. Given that it is now known that most peptic ulcers are caused by Helicobacter pylori, the merit of swallowing a live slug is questionable. A clear mucus produced by the slug is also used to treat various skin conditions including dermatitis, warts, inflammations, calluses, acne and wounds.[12]

Taxonomy

Of the six orders of Pulmonata, two – the Onchidiacea and Soleolifera – solely comprise slugs. A third family, the Sigmurethra, contains various clades of snails, semi-slugs (i.e. snails whose shells are too small for them to retract fully into) and slugs.[1]

The taxonomy of this group is in the process of being revised in the light of DNA sequencing.[13] It appears that pulmonates are paraphyletic and basal to the opisthobranchs which are a terminal branch of the tree. The family Ellobiidae are also polyphyletic.

- Subinfraorder Orthurethra

- Superfamily Achatinelloidea Gulick, 1873

- Superfamily Cochlicopoidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Partuloidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Pupilloidea Turton, 1831

- Subinfraorder Sigmurethra

- Superfamily Acavoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Achatinoidea Swainson, 1840

- Superfamily Aillyoidea Baker, 1960

- Superfamily Arionoidea J.E. Gray in Turnton, 1840

- Superfamily Athoracophoroidea

- Family Athoracophoridae

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea

- Subfamily Bulimulinae

- Superfamily Camaenoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Clausilioidea Mörch, 1864

- Superfamily Dyakioidea Gude & Woodward, 1921

- Superfamily Gastrodontoidea Tryon, 1866

- Superfamily Helicoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Helixarionoidea Bourguignat, 1877

- Superfamily Limacoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Oleacinoidea H. & A. Adams, 1855

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea Albers-Martens, 1860

- Superfamily Plectopylidoidea Moellendorf, 1900

- Superfamily Polygyroidea Pilsbry, 1894

- Superfamily Punctoidea Morse, 1864

- Superfamily Rhytidoidea Pilsbry, 1893

- Family Rhytididae

- Superfamily Sagdidoidera Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Staffordioidea Thiele, 1931

- Superfamily Streptaxoidea J.E. Gray, 1806

- Superfamily Strophocheiloidea Thiele, 1926

- Superfamily Parmacelloidea

- Superfamily Zonitoidea Mörch, 1864

References

- ^ a b Burton D. W. (January 1982). "How to be sluggish". Tuatara. 25 (2): 48–63.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:30155937, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=30155937instead. - ^ a b Branson, BA (1980). "The recent Gastropoda of Oklahoma, Part VIII. The slug families Limacidae, Arionidae, Veronicellidae, and Philomycidae". Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science. 60: 29–35.

- ^ ALONSO, MR; IBAÑE, M. "ESTUDIO DE PARMACELLA VALENCIENNESIl WEBB & VAN BENEDEN, 1836, Y CONSIDERACIONES SO-BRE LA POSICION SISTEMATICA DE LA FAMILIA P ARMACELLIDAE (Mollusca, Pulmonata, Stylommatopho-ra)."

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ DAYRAT, B (2009). "Review of the current knowledge of the systematics of Onchidiidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Pulmonata) with a checklist of nominal species". Zootaxa. 2068: 1–26.

- ^ SCHILTHUIZEN, M; THOME, JW (2008). "Valiguna flava (Heynemann, 1885) from Indonesia and Malaysia: Redescription and Comparison with Valiguna siamensis (Martens, 1867)(Gastropoda: Soleolifera: Veronicellidae)". Veliger. 50 (3): 163–170.

- ^ Pekarinen E. (1994) "Autotomy in arionid and limacid slugs". Journal of Molluscan Studies 60(1): 19-23. abstract

- ^ Less toxic iron phosphate slug bait proves effective

- ^ http://www.gardening-guru.co.uk/2010/04/11/slugs-traps-death-by-beer/ Beer Traps

- ^ Slugs and Osmosis

- ^ "Health and Medicals News - Man's brain infected by eating slugs". Retrieved 2006-03-15.

- ^ "Quave et al. Dermatological remedies in the traditional pharmacopoeia of Vulture-Alto Bradano, inland southern Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008; 4: 5". Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ White TR, Conrad MM, Tseng R, Balayan S, Golding R, de Frias Martins AM, Dayrat BA (2011) Ten new complete mitochondrial genomes of pulmonates (Mollusca: Gastropoda) and their impact on phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol Biol 11(1):295

Further reading

- Burton D. W. (January 1982). "How to be sluggish". Tuatara. 25 (2): 48–63.

External links

- Ohio State University slug fact sheet

- Pancake Slug (Veronicella sloanei) Info

- How to Get Rid of Garden Slugs- a wiki article

- Jumpings Slugs of the Pacific NW

- Land Slugs and Snails and Their Control (pub. 1959) hosted by the UNT Government Documents Department

- Slugs of Florida on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site