St George's Church, Trotton

| St. George's Church, Trotton | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 50°59′45″N 0°48′35″W / 50.995893°N 0.809682°W | |

| Location | Petersfield Road, Trotton, West Sussex GU31 5EN, United Kingdom |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | St George, Trotton |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founded | Disputed (c. 1240 or 14th century) |

| Dedication | St George |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 18 June 1959 |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Decorated[1] |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Chichester |

| Archdeaconry | Horsham |

| Deanery | Midhurst |

| Parish | Trotton |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Revd Edward Doyle |

St. George's Church is an Anglican church in Trotton, a village in the district of Chichester, one of seven local government districts in the English county of West Sussex. Most of the structure was built in the early 14th century. However, some parts date to around 1230,[2] and there is evidence suggesting an earlier church on the same site. In 1904, a largely intact and unusually detailed painting was found on the west wall depicting the Last Judgment as described in Matthew 25:31–46.

The church is dedicated to St. George, patron saint of England. The rector of St George's also oversees the parish of Rogate with Terwick, and most services are held at St. Bartholomew's church in Rogate: just two services a month take place at Trotton.[3] The church is also used once a month by the British Orthodox Church.[3] The church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building for its architectural and historical importance.[4]

History

Historians have disagreed about its age, and the existence of an older church on the same site. The tower has been dated by its architecture to between 1230 and 1240,[5][6] but other historians question this date and suggest the tower and the body of the church both date to the 14th century.[7][8] The porch appears to be a 17th century addition.[9] There is a tomb of Margaret de Camois in the nave. It has been suggested that its location there, rather than the chancel as would be expected for the family of the lord of the manor (which her surname suggests she was), may indicate that the church was built on the site of an earlier, smaller, church and the tomb was in the chancel of that church.[9] Local historian Roger Chatterton-Newman disagrees, saying there would be no need for a church on the site any earlier.[7]

A comprehensive restoration was undertaken by Philip Mainwaring Johnston[10] in 1904. The work cost £700 (£95,000 as of 2024),[11] and a time capsule containing details of the builders, church officials and contemporary world events was buried at the end of the job.[12]

Description and architecture

The church is situated in the village of Trotton, West Sussex, just off the A272 near the River Rother. It stands between the early 15th-century bridge over the river and the 16th-century manor house.[9][13]

The church has a plain, simple Decorated-style exterior, apart from the tower which is Early English style.[1][13] The nave and chancel are in a single chamber, separated by a narrow step instead of a chancel arch.[5][9] The tower stands at the western end of the church, and contains a ring of four bells hung for change ringing.[9][14] The tenor (largest) bell dates from 1908, the others from 1913; all were cast by John Taylor & Co.[14] The church is built of rubble with ashlar dressings. The roof of the main body is tiled; during the 14th century it had a thatched roof, but this was replaced in about 1400.[5] The tower roof is a shingled octagonal cap.[9]

Wall paintings

In 1904, the whitewash was removed from the west wall and a wall painting from the very early days of the church was discovered.[2] This, in itself, is not remarkable. Plenty of early churches have wall paintings; however, this one was unusually rich and detailed. In the centre is Jesus Christ, beneath him is Moses and on his right is the "Carnal Man" surrounded by the Seven Deadly Sins. On his left is the "Spiritual Man" surrounded by the Seven Acts of Mercy.[9] These two characters are depicted on the opposite sides of Christ than is usual in such depictions of the Last Judgement.[2] The red paintwork is mostly in good condition, although the Seven Deadly Sins have started to fade.[15]

There are also paintings on the north and south walls depicting the Camoys family. Camoys was the lord of the manor and it appears he had the church built primarily for his family. This would explain the unusual detail in the paintings. They were intended as rich decoration rather than simply for educating an illiterate congregation.[2]

Monuments

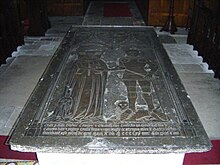

A 9-foot (2.7 m) table-tomb in the middle of the chancel contains the remains of Thomas de Camoys, 1st Baron Camoys (died 1421, although the inscription states 1419) and his wife Elizabeth Mortimer, a daughter of Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March. Baron Camoys fought at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, and his wife was the inspiration for the character of Gentle Kate in Henry IV by Shakespeare.[12] This is an unusually large brass, the couple being depicted only slightly smaller than life-size and holding hands.[15] The monument was described by Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner as "one of the biggest, most ornate and best preserved brasses in England".[15]

The nave contains a ledger stone with a brass of Margaret de Camois (died 1310).[2] This is the oldest known brass of a woman in England.[2][15] A 15th-century niche-tomb existed formerly in the south wall, but had been largely removed by 1780.[9][15] The table-tomb of Sir Roger Lewknor (died c. 1478) survives in the north-east corner of the chancel. Its sides display festoon motifs and slender sculpted niches.[15] In the south-east corner is the monument to Anthony Foster (died 1643), formed with pilasters.[15]

Churchyard

The churchyard contains a Commonwealth war grave, of a World War I soldier of the Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey).[17]

The church today

St George's Church was listed at Grade I on 18 June 1959.[4] Such buildings are defined as being of "exceptional interest" and greater than national importance.[18] As of February 2001, it was one of 80 Grade I listed buildings, and 3,251 listed buildings of all grades, in the district of Chichester.[19]

The present ecclesiastical parish of Trotton covers a large north–south area of countryside, includes the village of Trotton and the hamlets of Chithurst and Ingrams Green, and is served by St Mary's Church at Chithurst as well as St George's.[20] Both churches are in the Rural Deanery of Midhurst, one of eight deaneries in the Archdeaconry of Horsham in the Diocese of Chichester.[21][22]

Eucharistic services are held on the second and fourth Sundays every month. The church is open during the day for visitors.[3]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b Beevers, Marks & Roles 1989, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f Chatterton-Newman 1991

- ^ a b c "St George, Trotton". A Church Near You website. Archbishops' Council. 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ a b Historic England. "The Parish Church of St George, Trotton with Chithurst (1221344)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b c 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Pé 1998, p. 78.

- ^ a b Chatterton-Newman, Roger (1997). Camoys of Trotton. Rogate, UK: Rogate Society Occasional Papers.

- ^ Salter 2000, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salzman, L. F., ed. (1953). "A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 4: The Rape of Chichester. Trotton". Victoria County History of Sussex. British History Online. pp. 32–39. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Allen, John (28 March 2013). "Architects and Artists I–J–K". Sussex Parish Churches website. Sussex Parish Churches (www.sussexparishchurches.org). Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Wales 1999, p. 213.

- ^ a b Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 355.

- ^ a b "Trotton—S George". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 356.

- ^ Macklin, Herbert Walter & Page-Phillips, John, (Eds.), 1969, p.68

- ^ "St George's Churchyard, Trotton, with listed casualty". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Listed Buildings". Historic England. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Images of England — Statistics by County (West Sussex)". Images of England. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ "Trotton". A Church Near You website. Archbishops' Council. 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Rural Deanery of Midhurst". Diocese of Chichester. 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Archdeaconry of Horsham". Diocese of Chichester. 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

Bibliography

- Beevers, David; Marks, Richard; Roles, John (1989). Sussex Churches and Chapels. Brighton: The Royal Pavilion, Art Gallery and Museums. ISBN 0-948723-11-4.

- Chatterton-Newman, Roger (1991). Betwixt Petersfield and Midhurst. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-94-0.

- Coppin, Paul (2006). 101 Medieval Churches of West Sussex. Seaford: S.B. Publications. ISBN 1-85770-306-5.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071028-0.

- Pé, Diana (2008). West Sussex Church Walks. PP (Pé Publishing). ISBN 978-0-9543690-0-2.

- Salter, Mike (2000). The Old Parish Churches of Sussex. Malvern: Folly Publications. ISBN 1-871731-40-2.

- Vigar, John (1986). Exploring Sussex Churches. Rainham: Meresborough Books. ISBN 0-948193-09-3.

- Wales, Tony (1999). The West Sussex Village Book. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-581-1.

- Whiteman, Ken; Whiteman, Joyce (1998). Ancient Churches of Sussex. Seaford: S.B. Publications. ISBN 1-85770-154-2.

- Wilkinson, Edwin (2003). Looking Towards West Sussex Country Churches. Seaford: S.B. Publications. ISBN 1-85770-277-8.

External links