The Crack in the Picture Window

First edition | |

| Author | John Keats |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Don Kindler[1] |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Social criticism |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin[2] |

Publication date | 1956[2][1] or 1957[2][3] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 198 |

| ISBN | 9781258812645 |

The Crack in the Picture Window is a 1956 book of social criticism by the American writer John Keats.

Background

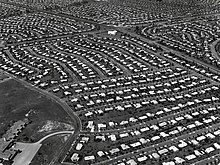

[edit]During the post–World War II economic expansion of the late 1940s and the 1950s, many persons from rural and urban backgrounds moved to single-family detached homes in the suburbs or in horizontally developed cities. It was not uncommon for some of these homes to have a picture window, in contrast to the smaller sash windows typical of urban and rural housing; although many of these new suburban homes did not necessarily have picture windows, Keats in his title used the term to characterize this new housing in general, and by extension the new social forms arising from this change in how people housed themselves (as well as other social changes of the time, such as those stemming from the popular adoption of television).[citation needed][original research?]

Keats's thesis

[edit]Keats, in this his first book,[4] took at dim view of the social changes brought on by the influx of population to the suburbs. According to Keats, this new mode of living entailed both physical inadequacies and psychological disadvantages. Builders of housing developments offered no-down-payment options which baited people to become overly indebted for homes often poorly designed, cheaply made, and soul-numbingly identical. At the same time, the social alienation of these neighborhoods, engendered by the replacement of the local markets with the supermarket, the inward-turning impetus of the television, and other changes, takes a psychological toll on the new suburbanites.[5]

Keats' uses the travails of the fictional couple John and Mary Drone to illustrate how the segregation of young couples of similar background, income bracket, and outlooks into homogeneous neighborhoods make for a stultifying unnatural community. Surrounded by neighbors but not true friends, they try to ameliorate their plight with gadgets such as televisions—which sinks them deeper into debt—or various activities including neighborhood sex.[2]

Keats critique is sometimes acerbic, as when he claims that "whole square miles of identical boxes are spreading like gangrene" across America because for nothing down "other than a simple two percent and a promise to pay, and pay, and pay until the end of your life" a person can "find a box of your own in one of the fresh-air slums" being built, "developments conceived in error, nurtured by greed, corroding everything they touch" which besides their effect to "destroy established cities and trade patterns [and] pose dangerous problems for the areas they invade" also even "actually drive mad myriads of housewives shut up in them".[1]

The Crack in the Picture Window was one of several critiques of 1950s American suburbia published around this time, such as Auguste Spectorsky's The Exurbanites (1955)[5] and Richard Yates's fictional indictment of suburbia, Revolutionary Road (1961).[4] Ginia Bellafante described The Crack in the Picture Window as "the book version" of the 1962 protest song "Little Boxes".[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Joe Bonomo (October 7, 2012). "The Crack In The Picture Window (review)". No Such Thing As Was. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The Crack in the Picture Window (review)". Goodreads. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Crack in the Picture Window (product description)". Abe Books. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ginia Bellafante (December 26, 2008). "The View From Revolutionary Hill". ArtsBeat. New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Crack in the Picture Window (review)". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved September 10, 2017.