Gloster thin-wing Javelin

| P.370/P.376 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Gloster Aircraft |

| Status | Cancelled, 1956 |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force (intended) |

| Developed from | Gloster Javelin |

The thin-wing Javelin refers to a series of design studies for an improved supersonic-capable version of the Gloster Javelin aircraft. Depending on the source, it is also known as F.153D, after its Air Ministry issued Operational Requirement, or the Super Javelin in some Gloster documents.

Gloster Aircraft had been studying a variety of updates and variations of the Javelin from before the first production model flew in 1953. These generated enough interest for the Air Ministry to ask for a version switching the Javelin's Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire engines for the more powerful Bristol Olympus. In September 1954, Gloster offered three minor variations on this concept, P.370 through P.372. In November 1954, the Air Ministry offered an official development contract for this "Thin Wing Gloster All-Weather Fighter", starting the construction of prototypes of the P.371 version which was expected to reach just over Mach 1.

During the design period, Bristol Siddeley began development of a major update to the Olympus. Moving to these engines offered much better performance. The ultimate version was the P.376, which featured a thinner wing and area ruled fuselage to lower wave drag, almost double the engine power of the original Javelin, and new intakes to improve airflow to the engines at supersonic speeds. These changes were expected to allow the design to reach Mach 1.6 at altitudes up to 60,000 feet (18 km) while carrying two of the very large Red Dean missiles.

The first of two P.371 prototypes was under construction when the project was cancelled in the spring of 1956 in favour of purchasing the Canadian Avro Arrow. The Arrow was expected to be available in 1959, two years before the P.376, and was also significantly faster. The Arrow purchase was also cancelled due to delays, and the money was redirected towards the Operational Requirement F.155 designs. F.155 was also cancelled the next year in the aftermath of the release of the 1957 Defence White Paper.

History

[edit]Javelin developments

[edit]The Gloster Javelin, ordered into production in 1953, was the RAF's first purpose-designed all-weather jet fighter and equipped with air-to-air missiles. It suffered from high transonic wave drag due to the thick cross-section of its wing, limiting its speed. Gloster had been exploring this problem for some time and offered an enlarged, thinned and lengthened outer wing section as part of their P.350 model, a photo-reconnaissance (PR) variant. This proved interesting enough for the Air Ministry to offer requirement F.118D around the design.[1]

At a design conference on 12 May 1953 with Gloster, the Ministry stated that Gloster's primary aim of the work should be to improve the overall performance of the Javelin, not just the PR version. They wanted more engine power, the ability to carry more armament, and the improved Mk. 18 (AI.18) aircraft interception radar. Estimates suggested that the design would be able to reach Mach 1.2 to 1.3 in a dive when equipped with uprated Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire Sa.10 engines. This became the P.356 design of July 1953.[2] A further development was P.364 of September 1953, which moved from the 14,000 lbf (62,000 N) Sa.10 to the new 16,000 lbf (71,000 N) Bristol Olympus Ol.6 and featured a modified vertical stabilizer suggested by the Royal Aircraft Establishment.[1]

At a meeting with the Air Ministry in January 1954, the extra power of the Olympus was considered ideal, especially as the equipment weight continued to grow. This led to the November 1954 specification F.153D for the Thin Wing Gloster All-Weather Fighter, officially released on 17 March 1955. In September 1954, P.364 became a series of three designs, P.370/371/372, differing largely in weapons fit; 370 mounted four 30 mm ADEN cannons[a], 371 two Red Deans[b], and 372 four Blue Jay missiles. The Olympus continued to improve, and by this time the Ol.7 version was capable of 17,160 pounds-force (76,300 N) while the simplified Ol.7SR had reached 20,550 pounds-force (91,400 N), which would allow the design to reach Mach 1.07 in level flight, and as high as 1.3 in a dive.[1]

In October 1955, Javelin FAW.1 XA564 was sent to Bristol Filton Airport to act as a testbed for the fitting of the Olympus.[3]

Competing designs

[edit]

In the summer of 1955, the Air Staff was able to examine the all-weather development of the American McDonnell F-101 Voodoo, which was able to reach Mach 1.6. A significant reason for this difference in performance was that the P.370 series had three times the amount of wing area. This gave it much better climb and high-altitude performance, but at the cost of higher drag and lower top speed.[1]

British military intelligence was already aware of Soviet bomber developments, notably the high-subsonic Myasishchev M-4 which were expected to enter service in 1959. To intercept the M-4 using pursuit-course weapons like the Blue Jay missile, the interceptor had to approach the bomber from the rear quarter. During World War II, Taffy Bowen had demonstrated that a fighter required a 20 to 25% speed over the bomber to arrange such an interception.[4] The Javelin already had marginal performance against existing bombers, and nowhere near this margin over the M-4. This could be addressed using a collision-course missile like Red Dean, which could be fired from the front, but it was already suffering from development issues that made its use in the near term seem questionable.[1]

Given these developments, it appeared that higher speed was much more important than climb rate or altitude performance. At a meeting at Gloster, they concluded that using improved reheat on the newer Ol.7R would increase performance to Mach 1.4 with a maximum altitude 66,000 ft. This compared much more favourably with the Mach 1.6 and 51,000 ft for the F-101. As this seemed competitive, the Air Ministry told Gloster to continue development,[1] and placed an order for 18 prototypes and pre-production examples.[5] Around the same time, initial planning for much faster aircraft began under OR F.155, able to deal with future supersonic bombers.[1]

In December 1955, at meetings in Washington DC, the Minister of Supply was given details of the Mach 2 Avro Arrow under development in Canada. The Minister was so impressed that he arranged for an evaluation team to visit Avro Canada in early 1956. Serious consideration was given to adopting the Arrow with British engines. Its Mach 2 speed meant it would be able to easily chase down the M-4 and attack it even with pursuit-course missiles, as well as known near-term supersonic developments like the Mach 1.5 Tupolev Tu-22 and Myasishchev M-50, which the British had learned about in late 1954. Better yet, the Arrow was expected to be available in 1959, two years earlier than the F.153 Javelin, eliminating the performance gap between the introduction of the M-4 and the F.155 designs that would enter service in 1963.[6]

P.376

[edit]In February 1956, the Ministry asked Gloster to consider additional changes to the design to further improve performance and what effect those changes might have on the timeline for delivery. Two changes were considered, modifying the fuselage to consider the area rule to further reduce drag, and further thinning the wings, especially the still-thick inner sections. The latter appeared to be difficult as it would require a structural redesign that would delay production and it would reduce fuel capacity. The former appeared relatively simple and appeared to not affect the timeline.[6]

By this time, Bristol had started a major update to the Olympus, the 200 series, to better compete with the upcoming Rolls-Royce Conway. The new design was roughly the same size and weight as the current Olympus, but offered significantly higher thrust. Bristol stated the new Ol.21 engines would be available in September 1958 with production models in early 1959.[6]

Combining the area rule and the new engines produced the ultimate version of the design series, P.376. It mounted two Red Dean missiles well forward on pylons roughly mid-span on the wing, giving it all-aspect capability against targets up to Mach 1.3. Maximum speed with 1,800 K of reheat would be Mach 1.63, improving to 1.79 at 2,000 K. It was expected that the prototype would be available in December 1958. The Ministry expressed some doubt about the predicted speed, given the still-thick wing, but did allow that it would still be much better than P.370.[6]

Cancellation

[edit]Design work on P.376 had only just started when, on 24 February 1956, the Air Council suggested cancelling the entire project. In April, they suggested buying Arrow, as the RAF was asking for a new fighter as soon as possible before replacing it with F.155. Another Gloster proposal for a strike variant as an English Electric Canberra replacement, which led to a draft OR.328, was cancelled on 20 March 1956.[6]

In a 3 May 1956 memo, the Ministry of Supply's Walter Monckton stated "the sooner Thin Wing Javelin is dropped the happier I shall be because every week of further development is a waste of money." The project was officially cancelled on 31 May and Gloster was ordered to stop work in June. At the time, the prototype XG336 was estimated to be some 60 to 70% complete and the first production models, the XJ series, were on the production jigs.[6]

The Arrow was ultimately dropped as well due to cost and delays, which had pushed its service date further toward the F.155 schedule. It was felt that the money earmarked for Arrow was better spent on getting F.155 into service earlier and prioritizing the Saunders-Roe SR.177 jet-rocket fighter-interceptor for high altitude. All of this ultimately led to nothing in the aftermath of the 1957 Defence White Paper, which cancelled all of these projects.[6]

Description

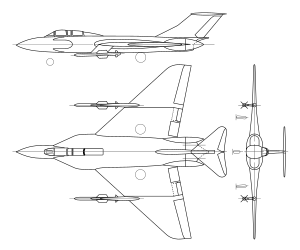

[edit]The P.376 was very similar to the Javelin in overall layout, with a large delta wing and a T-tail formed of smaller delta horizontal stabilizer at the top of the vertical stabilizer. The most apparent change from the ground was the overall larger size, with the cockpit area now forward of the wing and a large extension rearward for the engines, which previously ended flush with the end of the wing. These changes increased the length of the aircraft from 56 feet (17 m) to 72 feet (22 m). The engine intakes, which formerly faced flat to the airflow, were now angled sharply back at roughly 60 degrees. Another obvious change was the large teardrop-shaped extensions on either side of the engine nozzles, which increased the fuselage cross-section at the rear and thus helped improve the area rule considerations. Less obvious, and only really visible from above, was the wasp-waisting of the rear fuselage as part of the area rule design.[7]

Specifications (Gloster P.376)

[edit]Data from Buttler, page 55.[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 72 ft (22 m)

- Wingspan: 60 ft 8 in (18.49 m)

- Wing area: 1,235 sq ft (114.7 m2)

- Gross weight: 60,300 lb (27,352 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 2,200 gal internal plus 760 gal in ventral drop tanks

- Powerplant: 2 × Bristol Olympus Ol.21 afterburning turbojet engines, 28,500 lbf (127 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.82 at 36,000 ft (11,000 m)

- Service ceiling: 62,000 ft (19,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 56,000 ft/min (280 m/s)

Armament

- Missiles: Two Red Dean air-to-air missiles

Avionics

- Mk. 18 (AI.18) aircraft interception radar

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Buttler 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Buttler 2000, p. 52.

- ^ Simpson, Andrew (2012). "Gloster Javelin F(AW) 1 XA564/7464M" (PDF). RAF Museum.

- ^ White 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Bond 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Buttler 2000, p. 54.

- ^ James 1987, pp. 410–413.

- ^ Buttler 2000, p. 55.

Bibliography

[edit]- Buttler, Tony (2000). British Secret Projects 1: Jet Fighters Since 1950. Midland Publishing.

- Bond, Steve (2017). Javelin Boys: Air Defence from the Cold War to Confrontation. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-911621-58-4.

- James, Derek (1987). Gloster Aircraft Since 1917. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-85177-807-5.

- White, Ian (2007). The History of Air Intercept (AI) Radar and the British Night-Fighter 1935–1959. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-532-3.