Ungulate

| Ungulate Temporal range: Late Cretaceous - Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Llamas, which have two toes, are artiodactyls -- "even toed" ungulates. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superorder: | Ungulata

|

| Orders & Clades | |

| |

Ungulates (pronounced /ˈʌŋɡjʊleɪts/) are several groups of mammals, most of which use the tips of their toes, usually hoofed, to sustain their whole body weight while moving. The term means, roughly, "being hoofed" or "hoofed animal". They make up several orders of mammals, of which six to eight survive. There is some dispute as to whether Ungulata is a cladistic (evolution-based) group, or merely a phenetic group or folk taxon (similar, but not necessarily related), because not all ungulates appear as closely related as once believed. Ungulata was formerly considered an order which has since been split into:

- Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates),

- Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates),

- Tubulidentata (aardvarks),

- Hyracoidea (hyraxes),

- Sirenia (dugongs and manatees), and

- Proboscidea (elephants).

As a descriptive term, "ungulate" normally excludes cetaceans, which are now known to share a common ancestor with Artiodactyla and form the clade Cetartiodactyla with them. Members of the orders Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla are called the 'true ungulates' to distinguish them from 'subungulates' (Paenungulata) which include members from the afrotherian orders Proboscidea, Sirenia and Hyracoidea.[1]

Commonly known examples of ungulates living today are the horse, zebra, donkey, cattle/bison, rhinoceros, camel, hippopotamus, tapir, goat, pig, sheep, giraffe, okapi, moose, elk, deer, antelope, and gazelle.

Relationships

Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla comprise the largest portion of ungulates, and also include the majority of large land mammals. These two groups first appeared during the late Paleocene and early Eocene (about 54 million years ago), rapidly spreading to a wide variety of species on numerous continents, and have developed in parallel since that time.

Although whales and dolphins (Cetacea) do not possess most of the typical morphological characteristics of ungulates, recent discoveries indicate that they are descended from early artiodactyls, and thus are directly related to other even-toed ungulates such as cattle, with hippopotamuses being their closest living relatives.[2] As a result of these discoveries, the new order Cetartiodactyla has been proposed to include the members of Artiodactyla and Cetacea, to reflect their common ancestry; however, strictly speaking, this is merely a matter of nomenclature, since it is possible simply to recognize Cetacea as a subgroup of Artiodactyla.

Hyracoidea, Sirenia and Proboscidea comprise Paenungulata. Aardvarks are also thought to be ungulates. Some recent studies link Tubulidentata with Paenungulata in Pseudoungulata.[3] Macroscelideans have been interpreted as pseudoungulates as well, based on dental as well as genetic evidence. Genetic studies indicate that these animals are not closely related to artiodactyls and perissodactyls; their closest relatives are afrosoricidans. Pseudungulata, Macroscelidea and Afrosoricida together make up Afrotheria.

Ungulate groups represented in the fossil record include afrotherian embrithopods and demostylians, artiodactyl-related mesonychids, "condylarths" and various South American and Paleogene lineages.

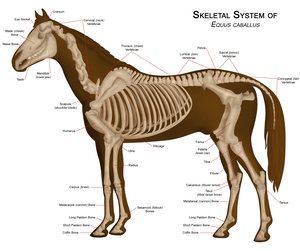

In addition to hooves, most ungulates have developed reduced canine teeth, bunodont molars (molars with low, rounded cusps), and an astragalus (one of the ankle bones at the end of the lower leg) with a short, robust head. Some completely lack upper incisors and instead have a dental pad to assist in browsing.[4][5]

In most modern ungulates, the radius and ulna are fused along the length of the forelimb; early ungulates, such as the arctocyonids did not share this unique skeletal structure.[6] The fusion of the radius and ulna prevents an ungulate from rotating its forelimb. Since this skeletal structure has no specific function in ungulates, it is considered to be a homologous characteristic that ungulates share with other mammals. This trait would have been passed down from a common ancestor.

Ungulates diversified rapidly in the Eocene, but are thought to date back as far as the late Cretaceous. Most ungulates are herbivores, but a few are omnivores or even predators (mesonychids and whales).

Recent developments

That these groups of mammals are most closely related to each other has been questioned on anatomical and genetic grounds. Molecular phylogenetic studies have suggested that Perissodactyla and Cetartiodactyla are closest to Carnivora and Pholidota rather than to Pseudungulata.

Pseudungulata is united with Afrosoricida in the cohort or super-order Afrotheria based on molecular and DNA analysis. This means they are not related to other ungulates.

The orders of the extinct South American ungulates, which arose when the continent was in isolation some time during the mid to late Paleocene, are united in the super-order Meridiungulata. They are thought by some to be unrelated to other ungulates. Instead, they may be united with Afrotheria and Xenarthra in the supercohort Atlantogenata.

Embrithopods, desmostylians and other related groups are seen as relatives of paenungulates, thus members of Afrotheria. Condylarths are, as a result, no longer seen as the ancestors of all ungulates. Instead, it is now believed condylarths are members of the cohort Laurasiatheria. So it seems that, of all the ungulates, only Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla descended from condylarths—assuming that the animals lumped by scientists into Condylarthra over the years are even related to one another.

As a result of all this, the typical ungulate morphology appears to have originated independently three times: in Meridiungulata, Afrotheria and the "true" ungulates in Laurasiatheria. This is a striking example of convergent evolution.[7] This idea has met with skepticism by some scientists, because of the lack of an obvious morphological basis for splitting the ungulates into so many unrelated clades.

See also

References

- ^ Mammology: adaptation, diversity, and ecology, Feldhammer, George A. 1999, p. 312

- ^ Ursing, B. M. (1998). "Analyses of mitochondrial genomes strongly support a hippopotamus-whale clade". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 265 (1412): 2251–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0567. PMC 1689531. PMID 9881471.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Seiffert, E.R.; Guillon, JM (2007). "A new estimate of afrotherian phylogeny based on simultaneous analysis of genomic, morphological, and fossil evidence" (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-224. PMC 2248600. PMID 17999766. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rouge, Melissa (2001). "Dental Anatomy of Ruminants". Colorado State University. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Toothless cud chewers, To see ourselves as others see us..." WonderQuest. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Christine M. Janis, Kathleen M. Scott, and Louis L. Jacobs, Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America, Volume 1. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 322-23.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2005). The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Mariner Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

External links

- Your Guide to the World's Hoofed Mammals - The Ultimate Ungulate Page