User:Matttbrown/sandbox

Operation Wetback (1954)[edit]

Operation Wetback was an immigration law enforcement initiative created by Director of the Immigration and Naturalization Service Joseph Swing. The program was implemented in May of 1954 by the U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell, and utilized special tactics to combat the problem of illegal border crossing and residence in the United States by Mexican nationals. [1] Ultimately, the program came as a result of pressure from the Mexican government to stop illegal entry of Mexican Laborers in the United States based largely on the Bracero Program. After implementation, Operation Wetback was met with allegations of abuse and suspension of certain civil rights of Mexicans that were captured and deported by U.S. Border Patrol. [2]

Background and causes[edit]

Migration and labor demands before WWII

Mexico began discouraging emigration to U.S. in early 1900s, beginning with President Profirio Diaz. [3] Diaz, like many others within the Mexican government, realized the laborers leaving for the United States would be needed to industrialize Mexico and grow the economy.[4] While the Government did not have extensive capital, its biggest asset was abundant, cheap labor, the primary source needed to modernize the country and utilize industrialized agri-business [5]The large and continuously growing agricultural industry in the United States created an demand for Mexican labor. From the 1920s onward, with the exception of the depression era, Mexicans served as the primary labor source for much of the agricultural industry in the United States, especially in the Southwest.[6] 62,000 workers entered the United States legally, while over 100,000 entered illegally per year during the 1920s. [7] Pressure from Agribusiness owners to return laborers from the United States to Mexico prompted increased action by the Mexican government. The labor problems grew so bad that crops would rot in the fields of Mexican Agribusinesses because so many laborers had crossed the border into the U.S.[8] Meanwhile, American farms were also transitioning to large scale farms and agribusinesses, and continued to recruit illegal mexican laborers to fulfill the increasing labor demands. [9]

The Bracero program (1942-1964)

The Bracero Program was a wartime agreement between Mexican and American Governments which allowed Mexican Laborers to work in United States under short term contracts in exchange for stricter border security and the return of illegal Mexican immigrants to Mexico.[10] Mexico would provide laborers to the U.S. instead of providing allied military support with the understanding that border security and illegal labor restrictions would be tightened by the United States.[11] The U.S. agreed based upon a strong need for cheap labor to support its agricultural businesses, while Mexico hoped to utilize the laborers returned from the United States to boost its efforts to industrialize and grow the economy and eliminate labor shortages. [12] The program began on September 27, 1942 when the first braceros were admitted into the United States under its labor agreement with Mexico. [13] As part of the program, braceros were supposed to be guaranteed wages, housing, food, and exemption from military service, however these terms were often disregarded by American farm owners. [14] After this agreement was reached, the Mexican government continued to pressure the U.S. to strengthen its border security, or face the suspension of the legal stream of Mexican laborers going into the U.S.[15] 2 Million Mexican nationals legally participated in the program during its existence, yet the program, and its ultimate ineffectiveness in limiting illegal immigration into the United States, was one of the primary factors influencing the implementation of Operation Wetback. [16]

Unauthorized migration after 1942

Despite the Bracero program, American growers continued to recruit and hire illegal laborers to meet their labor needs.[17] The Bracero program could not accomodate the number of Mexicans that wished to work in the United States, which resulted in those who were denied entry as a bracero illegally crossing into America in search of better wages and opportunity. [18] While the Mexican Constitution allowed citizens to cross borders freely with valid labor contracts, foreign labor contracts could not be made in the United States until an individual had already legally entered the country. [19]This technical conflict, combined with literacy exams and fees from INS formed significant obstacles for Mexican laborers wishing to seek higher wages and increased opportunities in the United States. Food shortages in were common in Mexico while most of foodstuffs produced were exported; hunger, along with a growing population prompted many Mexicans to attempt to enter the U.S., legally or illegally, in search of wages and a better life.[20] The privatization and mechanization of Mexican agriculture only added more problems to employment and labor issues in Mexico, providing yet another reason for Mexicans to enter America in search of higher wage jobs [21] With the growing diplomatic and security issues surrounding illegal border crossings, the INS increased its raids and apprehensions beginning in the early 1950s leading up to Operation Wetback. [22] The korean war and red scare also prompted tighter border security to prevent communist infiltration.[23]

Border control leading up to Operation Wetback[edit]

Before 1943, more U.S. Border control officers were posted along the country's Northern Border.[24] Pressure from angry Mexican land and farm owners frustrated with the Bracero program prompted the Mexican government to call a meeting in Mexico city with the United States Department of Justice, State, INS, and U.S. Border Patrol.[25] This meeting resulted in increased border patrol along the U.S. - Mexico border by the United States, yet illegal immigration still persisted.[26] One of the main issues was that increased pressure by the Mexican government did yield more deportations, but the Mexicans being deported would rapidly reenter the United States. To combat this issue, the Mexican and American governments developed a strategy in 1945 to deport Mexicans deeper into Mexican territory by a system of planes, boats and trains.[27] However, in 1954, negotiations surrounding the Bracero program broke down, prompting the Mexican Government to send 5 thousand troops to its border with the United States.[28] As a result, President Eisenhower appointed Gen. Joseph Swing to Commissioner of INS and charged him with fixing border control issue in order to stabilize labor negotiations with Mexico. [29]

Operation Wetback (1954): Implementation and tactics[edit]

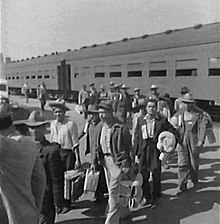

Operation Wetback was a system of Tactical Control and Cooperation within U.S. Border Patrol Agency and alongside the Mexican Government.[30] Planning between the INS led by Gen. Joseph Swing and the Mexican Government began in early 1954 while the program was formally announced in May 1954.[31] On May 17th, 1954 command teams of 12 Border Patrol agents, buses, planes, and temporary processing stations began locating, processing, and deporting Mexicans that had illegally entered the United States. 750 immigration and border patrol officers and investigators, 300 jeeps, cars and buses, and 7 airplanes were allocated for the operation.[32] Teams were focused on quick processing and deportation, as planes were able to coordinate ground efforts more quickly and increase mobility. [33] Those deported were handed off to Mexican officials, who in turn deported them into central Mexico where there were many labor opportunities.[34] While the operation would include the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago, its main targets were border areas in Texas and California. [35] Overall, there were 1,078,168 apprehensions made in the first year of Operation Wetback, with 170,000 being captured from May to July 1954.[36] The total number of apprehensions would fall to just 242,608 in 1955, and would continuously decline by year until 1962, when there was a slight rise in apprehended illegal workers.[37] During the entirety of the Operation, border recruitment byof undocumented workers by American growers continued due largely to the inexpensiveness of illegal labor and the desire of growers to avoid the bureaucratic obstacles of the Bracero program; the continuation of illegal immigration despite the efforts of Operation Wetback was largely responsible for the failure of the program.[38] Despite the decline in apprehensions, the total number of border patrol agents more than doubled to 1,692 by 1962, and an additional plane was also added to the force.[39] In terms of apprehensions, Operation Wetback was immediatley successful. However, this success would be short lived, as the program would fail to limit the number of workers entering the United States from Mexico illegally.[40] The program would also result in a more permanent, strategic border control presence along the United States - Mexico border.[41]

Mistreatment and abuse[edit]

Operation Wetback uses the name "Wetback" which was a derogatory term applied to Mexicans laborers, both legal and illegal.[42] The ideology of the term wetback, as a persona and racial slur, was used to further steroetypes of Mexicans and prevent laborers from organizing.[43] One of the biggest issues with the program was the transportation of Mexicans to unfamiliar places, where they would struggle to find their way home or support their families. [44] Over 25% of apprehended Mexicans were returned to Vera Cruz on ships, while others were transported by land to southern Cities in Mexico. [45] Apprehended illegals were often deported without opportunity to recover their property in America or contact family, and were stranded without food or employment when they entered Mexico. [46] Deported mexicans faced extreme conditions, and were left desert conditions; 88 recently deported workers died in 112 degree heat in July 1955.[47] Another issue was repeat border crossings by those who had been previously deported; from 1960-1961, repeaters accounted for 20% of the total deportees.[48] Certain U.S. Border patrol agents practiced shaving heads to mark repeat offenders who would attempt to reenter the United States. There was also reports of beating and jailing illegal immigrants before deporting them.[49] While most complaints concerning deportation were undocumented, there were over 11,000 formal complaints from documented bracero workers spanning from 1954 -1964.[50] Ultimately, with the lack of evidence and documentation concerning the treatment of illegal laborers in Operation Wetback, the level of mistreatment unclear and unknown.

References[edit]

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 421-444.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p.430, 437-440.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 425.

- ^ Hernandez 2006 p. 425.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 430.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 127-130.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 138-139.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 139.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 428.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 138.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 139, 143.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 430.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 428.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 146-147.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 147-148.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 425.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 426-428.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 152-153.

- ^ Avi 2009, p. 5-29

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 429.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 429-430.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 429-430.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 430-431.

- ^ Hernandez 2006 p. 433.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 444.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 442.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 441-442.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 155.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 441-444.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 156-157.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 152, 158-160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p.157.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p.157-160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 157-160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 443.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 156, 160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 437-439.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 143.

Sources[edit]

Astor, Avi. ″Unauthorized Immigration, Securitization, and the Making of Operation Wetback.″ Latino Studies 7 (2009): 5-29.

Hernandez, Kelly L. ″The Crimes and Consequences of Illegal Immigration: A Cross Border Examination of Operation Wetback, 1943-1954.″ Western Historical Quarterly 37 (2006): 421-444.

Mize, David. Consuming Mexican Labor: From the Bracero Program to NAFTA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Matttbrown (talk) 01:44, 25 February 2013 (UTC)

Matttbrown (talk) 01:51, 18 March 2013 (UTC)

Matttbrown (talk) 00:07, 9 April 2013 (UTC)

Comments[edit]

Hi Matt--This looks promising, but may need some reorganization. I think you should treat this material chronologically, starting with the tightening of the border in the 1920s moving forward to the Bracero program and its problems. The trick here is to provide enough history on border control policies and the Bracero Program to allow the reader to understand why Operation Wetback was launched, but not to repeat too much of what is already in other WP articles. Make sure you provide links to the relevant programs and legislation and that your info on those things jibes with what's in the other articles. I like your introductory graph so far, but you'll want to add another sentence or two about the impact of and controversy surrounding Operation Wetback. Since anything relating to immigration is controversial these days, be especially careful to maintain a NPOV by presenting pro and con perspectives.Docjay57 (talk) 15:02, 8 March 2013 (UTC)