User:Wikiprodigi/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Wikiprodigi. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

| This is a user sandbox of Wikiprodigi. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

| This is a user sandbox of Wikiprodigi. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Cultures and traditions

The attempts to explain the universe stem from observations of the objects found in the sky. Different cultures historically have various stories to provide an answer to the questions of what they are seeing. Norse Mythology originates from eastern Europe, around the geographical location of modern-day region of Scandinavia and Northern Germany. The Norse mythology consists of tales and myths derived from Old Norse, which was a Northern German language from the Middle Ages. There is a series of manuscript texts written in Old Norse which contain a collection of [35] poems written from oral tradition.[1] Among historians there seems to be speculation of the specific dates of the poems written, however, the estimated record of the texts is around the beginning of the thirteenth century.[2] Although the oral tradition of passing down tales existed long before the advent of text manuscripts and print versions.

The collection of poems is split into sections of mythology and heroics. Among surviving texts there is mention of the mythological god, Odin. Scholars have recounted the tale of the Αesir Gods creation myth which includes the idea of fixed stars found within the teleology of the tale. Padaric Colum has written a book, The Children of Odin, which in much detail reiterates the story of how the Aesir god’s brought the giant named Ymir to his demise and created the world from his body, affixing sparks from the fiery Muspelheim to the dome of the sky which was the skull of Ymir.[3] The Norse creation myth is one of several cases which treated stars as being fixed to a sphere beyond the earth. Later scientific literature shows astronomical thought which kept a version of this idea until the seventeenth century.

Western astronomical culture

Western astronomical knowledge was based on the traditional thoughts from philosophical and observational inquiries of Greek Antiquity. Other cultures contributed to thought about the fixed stars including the Babylonian’s, who from the eighteenth to the sixth century BC constructed constellation maps. Maps of the stars and the idea of mythological stories to explain them was largely being acquired all over the world and in several cultures. One similarity between them all was the preliminary understanding that the stars were fixed and immobile in the universe. This understanding was incorporated into theorized models and mathematical representations of the cosmos by philosophers like Anaximander and Aristotle from the Ancient Greeks. Anaximander wrote a treatise, of which only few excerpts remain. In this work he states his proposed order of the celestial objects, the sun moon and the fixed stars. The stars he mentions are apertures of “wheel-like condensations filled with fire,” situated nearest to the earth in this system.[4] The records of Anaximander’s work left in fragments only gives a slight insight into reconstructing his intended meaning in understanding his views of the cosmos. Anaximander proposed a differing perspective from other later astronomers in proposing the fixed stars were nearest of the heavenly bodies to the earth. Other models of the planetary system show a celestial sphere containing fixed stars on the outer most part of the universe.

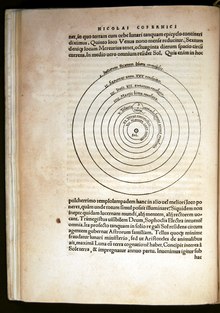

Aristotle and other like Greek thinkers of antiquity, and later the Ptolemaic model of the cosmos demonstrated an Earth centered universe. This Geocentric view was held through the Middle Ages and was later countered by subsequent astronomers and mathematicians alike, such as Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler. The tradition of thought which appears in all of these systems of the universe, even with their divergent mechanisms, is the presence of a celestial sphere which contains the fixed stars. Ptolemy was influential with his heavily mathematical work, The Almagest, which attempts to explain the peculiarity of stars that the moved. These “wandering stars,” planets, moved across the background of fixed stars which were spread along a sphere surrounding encompassing the universe. Later on, contemporary astronomers and mathematicians, like Copernicus challenged the long-standing view of geocentrism and constructed a sun centered universe, this being known as the heliocentric system. His system still upheld the tradition of a celestial sphere holding the fixed stars. Kepler also provided a model of the cosmos in his 1596 book Mysterium Cosmopgraphicum which pictures an image, labelled originally in Latin a "sphaera stellar fixar," or a sphere of fixed stars.

- ^ Bray, Oliver (1908). The Elder or Poetic Edda; commonly known as Saemund's Edda. Edited and translated with introd. and notes by Oliver Bray. Illustrated by W.G. Collingwood (1 ed.). archive.org: London Printed for the Viking Club. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. books.google.com: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Colum, Padaric (March 2, 2008). [www.gutenberg.org/files/24737/24737-h/24737-h.htm The Children of Odin: The Book of Nothern Myths]. Guternberg Project: Gutenberg Project eBook. pp. 62–69. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Khan, Charles (1960). Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 84–85.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)