Varanopidae

| Varanopidae Temporal range: Late Carboniferous - Middle Permian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil skeleton of Varanops brevirostris in the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Family: | †Varanopidae Romer and Price, 1940 |

| Genera | |

|

See below | |

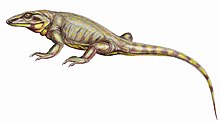

Varanopidae is an extinct family of amniotes that resembled monitor lizards and may have filled a similar niche, hence the name. Typically, they are considered synapsids that evolved from an Archaeothyris-like synapsid in the Late Carboniferous. However, some recent studies have recovered them being taxonomically closer to diapsid reptiles.[1][2][3] A varanopid from the latest Middle Permian Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone is the youngest known varanopid and the last member of the "pelycosaur" group of synapsids.[4]

Description

No known varanopids developed a sail like Dimetrodon. The length of known varanopids, including the tail, varies from 1 to 2 metres (3 to 7 ft).[5] Varanopids already showed some advanced characteristics of true pelycosaurs such as their deep, narrow, elongated skulls. Their jaws were long and their teeth were sharp. However, they were still primitive by mammalian standards. They had long tails, lizard-like bodies, and thin legs. The varanopids were mostly carnivorous, but as they were reduced in size, their diets changed from a carnivorous to an insectivorous lifestyle. Compared to the other animals in Early Permian, varanopids were agile creatures.

The genus Ascendonanus provides the first extensive skin impressions for ancient amniotes, revealing scales akin to those of squamates.[6] Parental care is known in Heleosaurus, suggesting that it is ancestral to synapsids as a whole.[7]

Varanopids are small to medium-sized possible synapsids that have been discovered throughout the supercontinent Pangea. Varanopids are found in formerly areas of North America, Russia, Europe, and South Africa. The authors Romer and Price (1940) discussed the original positioning of Varanopidae within Synapsida and considered them as the suborder Sphenacodontia. Most phylogenetic analyses have place Varanopidae as a basal member of Synapsida and due to their positioning, a better understanding of the morphology and phylogeny of varanopids is needed for synapsid evolution. The phylogeny of varanopids is based mostly on cranial morphology.[8][9] The atlas−axis complex can be described with little effort with variation of this structure within a small clade. Varanopids, members of synapsid predators have well preserved atlas−axes permitting a descriptions and examination of morphological variation between taxon. The size of the transverse processes on the axis and the shape of the axial neural spine can be variable. For the small mycterosaurine varanopids, they have a small transverse processes that point posteroventrally, and the axial spine is dorsoventrally short, with a flattened dorsal margin in lateral view. The larger varanodontine varanopids have large transverse processes with a broad base, and a much taller axial spine with a rounded dorsal margin in lateral view. Using outgroup comparisons, the morphology of the transverse processes is considered a derived trait in varanodontines, while in mycterosaurines the morphology of the axial spine is the derived trait.[10]

Ecology

At least some varanopids like Ascendonanus and Eoscansor are amongst the oldest known tree climbing (arboreal) animals, with limbs and digits adapted for grasping. Other varanopids lacked these adaptations and were probably terrestrial.[11]

Classification

Family Varanopidae

- Apsisaurus

- Archaeovenator

- Ascendonanus

- Basicranodon (possible junior synonym of Mycterosaurus[12])

- Eoscansor

- Dendromaia

- Pyozia

- Thrausmosaurus? (nomen dubium)

- Clade Neovaranopsia[13]

- Subfamily Mesenosaurinae

- Cabarzia

- Mesenosaurus

- Clade Afrothyra[13]

- Subfamily Varanodontinae

- Subfamily Mesenosaurinae

Apsisaurus was formerly assigned as an "eosuchian" diapsid. In 2010, it was redescribed by Robert R. Reisz, Michel Laurin and David Marjanović; their phylogenetic analysis found it to be a basal varanopid synapsid. The cladogram below is modified after Reisz, Laurin and Marjanović, 2010.[14]

| Varanopidae | |

The poorly known Basicranodon and Ruthiromia were tentatively assigned to Varanopidae by Reisz (1986), but have been neglected in more recent studies. They were included for the first time in a phylogenetic analysis by Benson (2012). Ruthiromia was found to be most closely related to Aerosaurus. Basicranodon was found to be a wildcard taxon due to its small amount of known materials, as it is based on a partial braincase from the ?Kungurian stage Richards Spur locality in Oklahoma. It occupies two possible positions, falling either as a mycterosaurine, or as the sister taxon of Pyozia. Although Reisz et al. (1997) considered Basicranodon as a subjective junior synonym of Mycterosaurus, Benson (2012) found some differences in the distribution of teeth and shape of the dentigerous ventral platform medial to the basipterygoid processes that may indicate taxonomic distinction. Below is a cladogram modified from the analysis of Benson (2012), after the exclusion of Basicranodon:[12]

| Varanopidae |

| ||||||

References

- ^ Ford, David P.; Benson, Roger B. J. (2018). "A redescription of Orovenator mayorum (Sauropsida, Diapsida) using high‐resolution μCT, and the consequences for early amniote phylogeny". Papers in Palaeontology. 5 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1002/spp2.1236. S2CID 92485505.

- ^ Modesto, Sean P. (January 2020). "Rooting about reptile relationships". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (1): 10–11. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-1074-0. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 31900449. S2CID 209672518.

- ^ MacDougall, Mark J.; Modesto, Sean P.; Brocklehurst, Neil; Verrière, Antoine; Reisz, Robert R.; Fröbisch, Jörg (2018). "Commentary: A Reassessment of the Taxonomic Position of Mesosaurs, and a Surprising Phylogeny of Early Amniotes". Frontiers in Earth Science. 6. doi:10.3389/feart.2018.00099. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ Modesto, S.P.; Smith, R.M.H.; Campione, N.E.; Reisz, R.R. (2011). "The last "pelycosaur": a varanopid synapsid from the Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone, Middle Permian of South Africa". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (12): 1027–1034. Bibcode:2011NW.....98.1027M. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0856-2. PMID 22009069. S2CID 27865550.

- ^ Reisz, R.R. & Laurin, M. (2004). "A reevaluation of the enigmatic Permian synapsid Watongia and of its stratigraphic significance". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 41 (4): 377–396. Bibcode:2004CaJES..41..377R. doi:10.1139/e04-016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frederik Spindler; Ralf Werneburg; Joerg W. Schneider; Ludwig Luthardt; Volker Annacker; Ronny Rößler (2018). "First arboreal 'pelycosaurs' (Synapsida: Varanopidae) from the early Permian Chemnitz Fossil Lagerstätte, SE Germany, with a review of varanopid phylogeny". PalZ. in press. doi:10.1007/s12542-018-0405-9.

- ^ Botha-Brink, Jennifer. "A Mixed-Age Classed 'Pelycosaur' Aggregation from South Africa: Earliest Evidence of Parental Care in Amniotes?" Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274.1627 (2007): 2829-834. JSTOR. Web. 06 Mar. 2017

- ^ Maddin, H. C.; Evans, D. C.; Reisz, R. R. (2006). "An Early Permian Varanodontine Varanopid (Synapsida: Eupelycosauria) from the Richards Spurs Locality, Oklahoma". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 957–966. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[957:AEPVVS]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524646.

- ^ Campione, N.; Reisz, R. (2010). "Varanops brevirostris (Eupelycosauria: Varanopidae) from the Lower Permian of Texas, with Discussion of Varanopid Morphology and Interrelationships". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 724–746. doi:10.1080/02724631003762914. S2CID 84949154.

- ^ Campione, N. E.; Reisz, R. R. (2011). "Morphology and Evolutionary Significance of the Atlas-axis Complex in Varanopid Synapsids" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 739–748. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0071.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Rinehart, Larry F.; Celeskey, Matthew D.; Berman, David S.; Henrici, Amy C. (June 2022). "A Scansorial Varanopid Eupelycosaur from the Pennsylvanian of New Mexico" (PDF). Annals of Carnegie Museum. 87 (3): 167–205. doi:10.2992/007.087.0301. ISSN 0097-4463.

- ^ a b Benson, R.J. (2012). "Interrelationships of basal synapsids: cranial and postcranial morphological partitions suggest different topologies". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (4): 601–624. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.631042. S2CID 84706899.

- ^ a b Spindler, F.; Werneburg, R.; Schneider, J. W.; Luthardt, L.; Annacker, V.; Rößler, R. (2018). "First arboreal 'pelycosaurs' (Synapsida: Varanopidae) from the early Permian Chemnitz Fossil Lagerstätte, SE Germany, with a review of varanopid phylogeny". PalZ. 92 (2): 315–364. doi:10.1007/s12542-018-0405-9.

- ^ Robert R. Reisz, Michel Laurin and David Marjanović (2010). "Apsisaurus witteri from the Lower Permian of Texas: yet another small varanopid synapsid, not a diapsid". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1628–1631. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501441. S2CID 129835335.

External links

- Varanopseidae - at Palaeos