William E. Sawyer

William E. Sawyer | |

|---|---|

| Born | William Edward Sawyer 1850 |

| Died | April 15, 1883 (aged 33) |

| Resting place | Cemetery |

| Occupation | Electrician |

| Children | 3 |

William Edward Sawyer (1850 – April 15, 1883) was an American inventor in the field of electrical engineering and electric lighting. His electric lamps were used to illuminate the Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. He was one of the founders of the Electro-Dynamic Light Company that manufactured incandescent electric lamps and developed city electrical distribution systems. He won many lawsuits against Thomas A. Edison for the invention of the incandescent electric lamp. Sawyer had dozens of patents, with some of his inventions related to electric lights, electric meters, telegraph facsimile machines, and television technology.

In 1880, he shot a medical doctor in the face in an incident stemming from a quarrel between their wives. The shooting left the doctor with permanent eye damage and Sawyer was sentenced to four years of hard labor for assaulting with intent to do bodily harm. However, he died in 1883 before starting his sentence, and many expected the Governor of New York to pardon him.

Early life

Sawyer was born in 1850 in Brunswick, Maine. His first job after graduating from high school was as a telegraphic reporter for The Boston Post.[1] He was noted for his technical ability as an outstanding shorthand writer, as his style was simple and his speed far above others that did shorthand.[2] On one occasion in 1871 he reported a speech of Wendell Phillips in the evening, a speech of between 7000 and 8000 words, and unaided in any way transcribed his notes in time to print them the next morning as his article titled "Voices For Freedom."[3] This was considered an extraordinary feat at the time among newspaper reporters.[4]

Early career

In 1873, Sawyer became a journalist with the Boston Evening Traveller in their Washington, D.C. office. He left Washington in November 1875 and relocated to New York City and began working as an electrician for the United States Electric Engine Company.[5] He was fired from the company due to his alcoholism and consequent bad attitude. Hiram Maxim (who would later go on to be involved with the invention of the light bulb, the maxim gun, and other important innovations of the late 19th and early 20th century) worked as chief engineer for the company during Sawyer's tenure at the company.[1]

Sawyer first took an active interest in incandescent lighting in 1875 after some initial experimentation in this field a few years earlier. He had developed his interest in lighting while working as the chief electrician of the Western Union Telegraph Company. He quit his full-time job in 1876 and devoted his entire attention to electrical experimentation and by 1877 he was developing out the Sawyer Electric Lamp.[6] He made several electric lamps which employed graphite burners in vacuums and atmospheres of nitrogen and constructed one which used a platinum illuminate.[7][8] The use of nitrogen was abandoned and a vacuum was introduced in it place. The pencil of carbon was replaced with a filament of material and the long tube was changed for a small glass globe.[9]

Albon Man, a middle-aged lawyer from Brooklyn, agreed in January 1878 to finance Sawyer's electrical experiments. They set up a workshop early in February at 43 Centre Street in New York City. Man had a deep interest in scientific matters ever since the time he had taken natural science courses while in college.[10] He became personally interested in the work of invention and collaborated with Sawyer on his experiments. By June three patents were issued to Sawyer and Man as joint inventors. Soon after that Sawyer, as an electrician, developed 25 inventions that were patented that solved electrical problems, some of which were patented jointly with Man.[11]

Inventions

One entirely new concept Sawyer invented was an automatic cut-off switch patent that cut the power on an overloaded circuit.[12] An electrical improvement from others was that instead of full power voltage application of electricity upon being turned on was a device that gradually raised the voltage to an electric lamp so that it didn't burn out upon receiving the electrical power.[13] His novel improvement of an electrical central power station that could be placed in various parts of a city made for better electricity distribution. Sawyer devised the first practical commercial electric meter so energy consumption could be recorded and billed accordingly.[14] An improvement in his electrical lighting was when he redesigned a new type of electric lamp that could operate for one-fortieth the cost of gas for the same illumination. Sawyer was inspired to contrive many electrical devices that solved many problems of the day that baffled other engineers and ultimately patented seventy-five of his apparatuses.[12]

A 1920 article in N.Y. Times described him as a pioneer in the development of the filament incandescent lamp.[15] Sawyer with his business partner Albon Man and other investors founded the Electro Dynamic Light Company in 1878 to produce electrical light and electric power. The company manufactured and sold all the machinery necessary for the lighting of streets and buildings, based on patents developed by Sawyer.[16] The company also was to manufacture the incandescent Sawyer-Man electric lamp which was patented in 1877. The electric lamps would cost a fraction of that of gas lamps to operate.[17]

The Electro-Dynamic Light Company successfully defended their patents against the Edison company from 1879 through 1885.[18] Sawyer and Man secured their patents according to official records to the first incandescent electric light on June 25, 1878.[19][20] Edison contested before the Patent Office their claim to the patent, but it was determined he was a year behind Sawyer and Man.[21] The Examiner of Interferences and Examiner-in-chief decided three times in the favor of Sawyer of having all rights to the incandescent conductor for the electric lamp patent.[22][23]

Sawyer and Man transferred their patent rights to their company, and proceeded to sue Edison's companies in 1883 for patent infringement.[24] The patents were transferred to the Thomson-Houston Electric Company in 1885 and they manufactured the electric incandescent lamps.[25] In 1887, Westinghouse Electric bought the company that manufactured the lamps.[26] The Sawyer-Man based 'stopper' lamps as they were called, although did not last as long as the Edison lamp, did allow Westinghouse to illuminate the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 successfully.[27] The Sawyer-Man company was eventually purchased by the Westinghouse Corporation and became the Westinghouse lighting division.[28]

- His inventions included these lighting patents listed below.

- The patents of 1878–1882 with associated patent name.

- 205,144 – Jun 18 1878 – Electric lamp – (with Albon Man)

- 205,303 – Jun 25 1878 – Electric lighting system – (with Albon Man)

- 205,305 – Jun 25 1878 – Regulator for electric lights – (with Albon Man)

- 210,151 – Nov 19 1878 – Electric meter

- 210,152 – Nov 19 1878 – Switch for electric lights – (with Albon Man)

- 210,809 – Dec 10 1878 – Electric lamp – (with Albon Man)

- 211,262 – Jan 07 1879 – Carbon for electric lights – (with Albon Man)

- 219,771 – Sep 16 1879 – Electric lamp

- 229,335 – Jun 29 1880 – Carbon for electric lights

- 229,476 – Jun 29 1880 – Electric switch

- 229,335 – Jun 29 1880 – Carbon for electric lights – (with Albon Man)

- 229,476 – Jun 29 1880 – Electric switch – (with Albon Man)

- 235,460 – Dec 14 1880 – Electric-lighting switch –

- 236,460 – Jan 11 1881 – Automatic regulator for electric currents –

- 237,632 – Feb 08 1881 – Dynamo-electric machine

- 241,242 – May 10, 1881 – Armature for dynamo-electric machines – (with E. R. Knowles)

- 241,430 – May 10, 1881 – Electric lamp – (with R. Street)

- 10,134 (reissue – Jun 6 1882) – Electric lighting system – (with Albon Man)

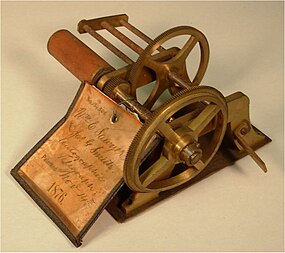

Autographic telegraph facsimile machine

Sawyer and James G. Smith of Hackensack, New Jersey, invented a machine (patent No. 184,302 dated November 14, 1876) by which they claim facsimiles of letters, pictures, or maps may be transmitted by telegraph. They asserted that by the use of their fac-simile telegraph instrument that the process of mistakes and willful changes were impossible. The speed of the inventors' facsimile machine for transmission of an image is gauged by the amount of surface covered of the transmitted material and not the number of words. The inventors say that 500 words, written within a certain space are as easily and quickly sent at the same cost as one word within the same space. The speed of the autographic telegraph facsimile telegram was three to four times that of the normal Morse telegraph telegram. The Sawyer facsimile machine could transmit forty to sixty words a minute in a hand written message of letters close to each other, while an expert telegraph operator keyed words at top speed of about fifteen words a minute.[29]

The inventors claimed that the use of their machine placed in the various signal service stations would be of much interest because as the reports to the headquarters could be made more complete and minute and the return reports more satisfactory and comprehensible than they can be done by the ordinary word map then furnished by the common telegraph. A dispatch could have within two hours available to any part of the United States an extensive updated weather report of information received from 100 signal stations after the conclusions are made.[29] The inventors considered their autographic telegraph facsimile machine to be of commercial value because images could be copied and delivered anywhere in the United States within hours that otherwise took days or weeks,[30] so they attempted to get sufficient capital to form an initial telegraphic line between New York City and Washington, D.C.[31]

-

1875 Autographic Improvement[32]

-

1876 Autographic Telegraph

-

Autographic Telegraph sync apparatus

Television construction plans

In October 1877, Sawyer had invited various figures in the New York electrical industry to the offices of his electrical engineering company in Lower Manhattan at No. 21 Cortlandt Street.[33] He presented construction plans to these witnesses of potential investors and other electricians for a device that properly combined most of the principles of television.[34] Others electricians years later came up with the same technology as Sawyer already had.[35][36][37] One such person was George R. Carey, also a surveyor for the city of Boston. In a meeting that happened sometime between February 1879 and May 1880 Sawyer and Carey talked over the technology involved in 'Seeing by Electricity' that later became known as television.[38]

Sawyer was made aware that Carey was going to publish an article in Scientific American to take credit for devising the technology. When Carey's article titled 'Seeing by Electricity' came out on June 5, 1880, Sawyer immediately sent a rebuttal article to the editors of Scientific American that it was his ideas originally that Carey just took from him that he was trying to get credit for. That article also titled 'Seeing by Electricity' was published a week later on July 12, 1880. In Sawyer's article he criticizes Carey in not knowing the exact technology involved in such a scheme. Sawyer pointed out that he had already presented the system years before to several witnesses at his company.[38]

Shooting incident

Sawyer intentionally shot Dr. Theophile Steele in New York City about April 5, 1880. He was being held in jail on $1,000 (equivalent to $32,000 in 2023) bail waiting trial.[39] It appears that, according to the New York Star newspaper, sometime in December 1879 Dr. Steele and his family were renting rooms in the boarding-house of Mrs. Manley, on west Forty-second street in New York City. In that same boarding-house Sawyer and his family were renting rooms. Sawyer often had fights with his wife, which annoyed the other tenants. The landlady requested that they move, but Sawyer refused. Mrs. Manley went to local court and obtained an eviction order and had it served upon Sawyer by the police. He didn't want to move until May 1, but was notified by the police that he would be physically moved out on Thursday April 1, 1880. Sawyer and his family then moved to a boarding house on the south side of west Forty-second street at the corner of Seventh avenue.[40]

A few days prior to this Mrs. Manley asked Dr. Steele to help her persuade Sawyer to move, but he refused to get involved. About this time Mrs. Sawyer, who was an alcoholic according to a son of Dr. Steele, complained to her husband that Mrs. Steele had spit on her from her apartment window. Mrs. Steele, who was a lady from Kentucky, claimed she was innocent of such rudeness, and when Steele was spoken to about the matter by Sawyer, he reiterated his wife's denial and declared in forcible terms that his wife had not told the truth about this dastardly deed. On the following day Dr. Steele received an offensive letter by mail from Sawyer, which he ignored.[40]

Dr. Steele:

Sir – You took me somewhat by surprise last evening. I could not then form as cool a judgment as might have been desirable. Since then I have learned that you occupied yourself in threatening to eat me up, etc. I have also determined that you have been for some time a little inclined to being a bully, particularly as I have received no word or excuse or apology for what last evening might have been hasty action on your part. Oblige me hereafter by passing me as a stranger, but do not allow yourself to forget that 1 now hold myself responsible for anything you imagine Mrs. Sawyer did, or said, or thought, or could possibly have thought, or would liked to do, or would have been impelled to say. In view of your threats of personal violence, 1 have not yet decided what action to take beyond tins to you -that you may go to the devil, with all possible celerity, for all I care. Remember, you have begun this. My address is number 95 Fulton street.

Yours, W. E. SAWYER.[40]

Sawyer then by chance met Steele in the barroom of the Rossmore hotel and he attempted to speak with him, but Steele insisted that their acquaintanceship was at an end and brushed him off. Sawyer attempted to apologize for his letter, whereupon, being repelled, he drew a revolver and shot Steele in the right eye, permanently damaging the eye. Sawyer attempted to set up a plea of self defense even though Steele had not threatened him in any way.[40] On being arraigned Sawyer made a statement saying that the newspaper accounts were erroneous. He claimed that the shooting of Steele was in self-defense. He insisted he did not follow Steele to the hotel or even look at him there. He claimed that instead he was warned by his wife to look out for him, as Steele was under the influence of liquor and was in an ugly mood. He said that Steele had followed him out of the back door of the hotel and as he crossed Seventh avenue to go to his boarding house residence in the south side of Forty-second street Steele followed him instead of crossing the street and going directly home on the north side of the street.[41]

Sawyer went on to say that Steele grabbed him on the shoulder cussing him out and saying that he was going to kill him. He pointed out that Steele normally carried two pistols with him and that he had his right hand in his side pocket holding one of them. He said that he had asked the doctor to go home and did not want any trouble. Sawyer claimed that this apparently angered the doctor and that then he pulled a pistol out of his right pocket. Sawyer figured that Steele was about to kill him and if he had not shot him immediately in self-defense that he would have been killed. The shot struck Steel in the face in the right eye and nose area,[42] causing permanent damage to the eye and loss of sight.[40] The jury in the trial of Sawyer on April 25, 1881, found him guilty for shooting Steele and rendered a verdict of "guilty of assault with intent to do bodily harm".[42][43] The maximum penalty for such a crime is five years of hard labor at the state prison.[43][44] A pardon by Governor Cleveland was anticipated due to the efforts of his friends.[4] He was to serve a sentence of four years imprisonment for the crime, but had not been seat to the penitentiary yet pending an appeal for a pardon by Governor Cleveland that was based on the value to the country of his electrical inventive talents.[45] Sawyer was let out on bond awaiting a new trail being set up by his counsel, but his bondsman took him to jail on June 6, 1882, who feared that he might leave the state, even though he denied thinking about fleeing.[46]

Personal life

Sawyer died at the age of thirty-three in New York, New York, on May 15, 1883.[47] He had three infant girls at the time named Corinne, Gertrude, and Clara Belle. The children were taken before Judge Lawrence, in his Supreme Court Chambers, on a writ of habeas corpus on June 9, 1883. Their maternal grandmother, Abbie W. Dacie, sued to get custody of the infant girls. The children were taken into court by Mrs. Nellie Sawyer, their step-mother, who said that her late husband had requested her to care for them, and that she wished to do so. The attorney for Mrs. Dacie said that she had been appointed their guardian by the Probate court and that she was anxious and able to maintain them. Judge Lawrence remarked that the children seemed to have been well cared for by their stepmother,[48] but had not made a decision on this matter of as June 10, 1883.[49]

At the time of Sawyer's death he was under sentence of imprisonment in New York state prison at hard labor for four years for having shot Dr. Theophile Steele in May 1880. He died in the morning of 15th of the month at his home, 104 Waverly place, of hemorrhaging of the bowels. He had not begun his term of imprisonment, owing to the efforts of his counsel, Frank J. Pupignae, who secured the consent of the court that he should remain at home pending an appeal to the governor for his pardon, which condition was endorsed by Judge Gildersleeve and the jury who tried him, the district attorney, and Dr. Steele. After the shooting his first wife died and he married again. Sawyer's second wife and his children were left penniless.[50]

Sawyer was known as an electrician for most of his adult life. He was first given the title electrician in 1875 when he was employed for the United States Electric Engine Company.[5] He was chief electrician for Western Union Telegraph Company in 1877.[6] He was referred to as "the electrician" after his death in many occasions, an indicator of his notability in contemporary society for his work in this field.[51][52]

References

- ^ a b Wrege, Charles D. (1984). "William E. Sawyer and the Rise and Fall of America's First Incandescent Electric Light Company, 1878—1881" (PDF). Business and Economic History. 13: 31–48.

- ^ "Graham Bell". The Fall River Daily Herald. Fall River, Massachusetts. November 1, 1881. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Voices for Freedom". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. March 21, 1881. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "William E. Sawyer dead /Electrician, Stenographer, Reporter and Telegraph Operator". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. May 16, 1883. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b Klein 2010, p. 199.

- ^ a b "Sawyer's Electric Lamp". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati, Ohio. November 9, 1878 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 6.

- ^ Bright 1949, p. 50.

- ^ Childs 1885, p. 245.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 8.

- ^ Pope 1894, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Perman 2013, p. 109.

- ^ Perman 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 83.

- ^ "Light Inventor Honored". The New York Times. 20 July 1920. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ "Sawyer's Electric Lamp". The Daily Gazette. Wilmington, Delaware. November 5, 1878. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "An Electric Lamp". Reading Times. Reading, Pennsylvania. October 31, 1878. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Incandescent Conductor / Edison loses his case". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. October 9, 1883. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Electric Light". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. October 14, 1883. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "A Warning". The Buffalo Commercial. Buffalo, New York. October 15, 1883. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Latest News". The Great Bend Weekly Tribune. Sedgwick, Kansas. October 12, 1883. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Current Comment". The Great Bend Weekly Tribune. Great Bend, Kansas. August 10, 1883. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Far and Near". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. July 29, 1883. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Electricians at Law". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. June 18, 1883. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Origin and Growth of the Thomson-Houston Company". Western Electrician Magazine. 2 (9): 116. March 3, 1888.

- ^ Klein 2010, p. 281.

- ^ "They cost a Million". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. November 23, 1893 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Furtan, F.A. (2006). "Early development of the incandescent lamp". Industry Applications Magazine. Mar–Apr: 7–9.

- ^ a b "The Wonders of Telegraphy". Harvey County News. Newton, Kansas. November 16, 1876 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Fac-Similes sent by Lightning". Kansas Reporter. Wamego, Kansas. November 16, 1876 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Fac Simile Telegraph". New Orleans Republican. New Orleans, Louisiana. October 21, 1876 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ E. Tunnicliff Fox Collection (2021). "Patent Model – Improvement in Autographic Telegraphs". Hagley Museum. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Sawyer, W.E. (June 12, 1880). "Seeing by Electricity". Scientific American. 42: 373. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Television Engineering Pioneers". The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Seeing by Electricity". Denton Journal. Denton, Maryland. March 24, 1883 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Seeing by Electricity". The Morning Astorian. Astoria, Oregon. March 28, 1883 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Seeing by Electricity". Scientific American. 41: 299. June 5, 1880. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Sawyer, William (June 12, 1880). "Seeing by Electricity". Scientific American. 12: 373.

- ^ "Held for trial". The Saint Paul Globe. Saint Paul, Minnesota. April 7, 1880 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c d e "Sawyer shooting of Dr. Theophile Steele". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. April 8, 1880 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Sawyer's Story". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. April 9, 1880. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "Professor Sawyer Found Guilty". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. April 27, 1881. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "Verdict Rendered". The Norfolk Landmark. Norfolk, Virginia. April 26, 1881. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Electric Light Inventor Liable to be sent to Prison for Five Years". Buffalo Evening News. Buffalo, New York. April 28, 1881. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Condensed News". The Times. Streator, Illinois. May 16, 1883 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Current Events". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. June 7, 1882 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Death of an American Electrician". Electrical World. 1–2. Williams & Company: 303. 1883. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contest for Custody of the late Prof. W.E. Sawyer's children". The Brooklyn Union. Brooklyn, New York. June 9, 1883. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Late W.E. Sawyer's Children". The New York Times. New York, New York. June 10, 1883. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Before a Pardon Came". The Sun. New York, New York. May 16, 1883. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Summary of News". The Sun. Montpelier, Vermont. April 14, 1880. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "William E. Sawyer's". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. April 8, 1880. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

Sources

- Bright, Arthur (1949). The Electric-Lamp Industry. The MacMillan Company. ISBN 0405046901.

- Childs, Emery (1885). A History of the United States. H. Green. OCLC 1046511371.

- Klein, Maury (2010). The Power Makers. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781596918344.

- Perman, Statcy (2013). A Grand Complication. Atria Books. ISBN 9781439190104.

- Pope, Franklin Leonard (1894). Evolution of Electric Incandescent Lamp. Boschen & Wefer. OCLC 1049374612.

![1875 Autographic Improvement[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Sawyer_Autographic_Improvement.jpg/285px-Sawyer_Autographic_Improvement.jpg)