Urquhart Castle

| Urquhart Castle | |

|---|---|

| Near Drumnadrochit, Highland, Scotland | |

Urquhart Castle and Loch Ness | |

Urquhart Castle, Grant Tower | |

| Coordinates | 57°19′26″N 4°26′31″W / 57.324°N 4.442°W |

| Type | Curtain wall castle and tower house |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Historic Environment Scotland |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 13th to 16th centuries |

| In use | Until c. 1692 |

Urquhart Castle (/ˈɜːrkərt/ UR-kərt; Scottish Gaelic: Caisteal na Sròine) is a ruined castle that sits beside Loch Ness in the Highlands of Scotland. The castle is on the A82 road, 21 kilometres (13 mi) south-west of Inverness and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) east of the village of Drumnadrochit.

The present ruins date from the 13th to the 16th centuries, though built on the site of an early medieval fortification. Founded in the 13th century, Urquhart played a role in the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 14th century. It was subsequently held as a royal castle and was raided on several occasions by the MacDonald Earls of Ross. The castle was granted to the Clan Grant in 1509, though conflict with the MacDonalds continued. Despite a series of further raids the castle was strengthened, only to be largely abandoned by the middle of the 17th century. Urquhart was partially destroyed in 1692 to prevent its use by Jacobite forces, and subsequently decayed. In the 20th century, it was placed in state care as a scheduled monument and opened to the public: it is now one of the most-visited castles in Scotland and received 547,518 visitors in 2019.[1][2]

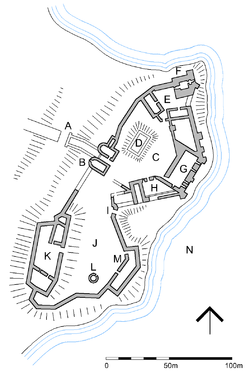

The castle, situated on a headland overlooking Loch Ness, is one of the largest in Scotland in area.[3] It was approached from the west and defended by a ditch and drawbridge. The buildings of the castle were laid out around two main enclosures on the shore. The northern enclosure or Nether Bailey includes most of the more intact structures, including the gatehouse, and the five-story Grant Tower at the north end of the castle. The southern enclosure or Upper Bailey, sited on higher ground, comprises the scant remains of earlier buildings.

History

[edit]Early Middle Ages

[edit]The name Urquhart derives from the 7th-century form Airdchartdan, itself a mix of the Old Irish aird (point or promontory) and Old Welsh cardden (thicket or wood).[4] Pieces of vitrified stone, subjected to intense heat and characteristic of early medieval fortification, had been discovered at Urquhart from the early 20th century.[5] Speculation that Urquhart may have been the fortress of Bridei son of Maelchon, king of the northern Picts, led Professor Leslie Alcock to undertake excavations in 1983. Adomnán's Life of Columba records that St. Columba visited Bridei some time between 562 and 586, though little geographical detail is given.[5] Adomnán also relates that during the visit, Columba converted a Pictish nobleman named Emchath, who was on his deathbed, his son Virolec, and their household, at a place called Airdchartdan.[6] The excavations, supported by radiocarbon dating,[7][8] indicated that the rocky knoll at the south-west corner of the castle had been the site of an extensive fort between the 5th and 11th centuries.[9] The findings led Professor Alcock to conclude that Urquhart is most likely to have been the site of Emchath's residence, rather than that of Bridei who is more likely to have been based at Inverness, either at the site of the castle or at Craig Phadrig to the west.[10][11]

The early castle

[edit]Some sources state that William the Lion had a royal castle at Urquhart in the 12th century,[12][13] though Professor Alcock finds no evidence for this.[14] In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Meic Uilleim (MacWilliams), descendants of Malcolm III, staged a series of rebellions against David I and his successors. The last of these rebellions was put down in 1229, and to maintain order Alexander II granted Urquhart to his Hostarius (usher or door-ward), Thomas de Lundin. On de Lundin's death a few years later it passed to his son Alan Durward.[15] It is considered likely that the original castle was built soon after this time, centred on the motte at the south-west of the site.[14] In 1275, after Alan's death, the king granted Urquhart to John II Comyn, Lord of Badenoch.[15]

The first documentary record of Urquhart Castle occurs in 1296 when it was captured by Edward I of England.[14] Edward's invasion marked the beginning of the Wars of Scottish Independence, which would go on intermittently until 1357. Edward appointed Sir William Fitz Warin as constable to hold the castle for the English. In 1297 he was ambushed by Sir Andrew de Moray while returning from Inverness, and Moray subsequently laid siege to the castle, launching an unsuccessful night attack.[16] The English must have been dislodged soon after, since in 1298 Urquhart was again controlled by the Scots. In 1303 Sir Alexander de Forbes failed to hold off another English assault.[17] This time Edward installed as governor Alexander Comyn, brother of John, as the family had sided with the English against Robert Bruce. Following his murder of the Red Comyn in 1306, Bruce completed his defeat of the Comyns when he marched through the Great Glen in 1307, taking the castles of Inverlochy, Urquhart and Inverness.[18] After this time Urquhart became a royal castle, held for the crown by a series of constables.[19]

Sir Robert Lauder of Quarrelwood was constable of Urquhart Castle in 1329. After fighting at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333, where the Scots were defeated, Lauder returned to hold Urquhart against another threatened English invasion. It is recorded as being one of only five castles in Scotland held by the Scots at this time (the others were Dumbarton, Lochleven, Kildrummy and Loch Doon).[19] In 1342, David II spent the summer hunting at Urquhart, the only king to have stayed here.[19]

Over the next two hundred years, the Great Glen was raided frequently by the MacDonald Lords of the Isles, powerful rulers of a semi-independent kingdom in western Scotland, with a valid claim to the earldom of Ross. In 1395, Domhnall of Islay seized Urquhart Castle from the crown, and managed to retain it for more than 15 years. His brother, Alexander Macdonald, Lord of Lochaber, also had a contract from Thomas Dunbar, Earl of Moray, to defend the Regality of Moray, which included access to the Great Glen. In 1411, Donald Macdonald marched through the glen on his way to claim the earldom of Ross. He met Alexander Stewart, earl of Mar at the Battle of Harlaw. Donald won the battle and retained control of Ross thereafter.[20] James I recognized his title as the first earl of Ross of his family. Nevertheless, the crown was soon back in control of Urquhart.[21][22]

In 1437 Domhnall's son Alexander, Earl of Ross, raided around Glen Urquhart but could not take the castle. Royal funds were granted to shore up the castle's defences. Alexander's son John succeeded his father in 1449, aged 16. In 1452 he too led a raid up the Great Glen, seizing Urquhart, and subsequently obtained a grant of the lands and castle of Urquhart for life. However, in 1462 John made an agreement with Edward IV of England against the Scottish King James III. When this became known to James in 1476, John was stripped of his titles, and Urquhart was turned over to an ally, the Earl of Huntly.[21][22]

The Grants

[edit]

Huntly brought in Sir Duncan Grant of Freuchie to restore order to the area around Urquhart Castle. His son John Grant of Freuchie (d.1538) was given a five-year lease of the Glen Urquhart estate in 1502. In 1509, Urquhart Castle, along with the estates of Glen Urquhart and Glenmoriston,[23] was granted by James IV to John Grant in perpetuity, on condition that he repair and rebuild the castle.[24] The Grants maintained their ownership of the castle until 1512, although the raids from the west continued. In 1513, following the disaster of Flodden, Sir Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh attempted to gain from the disarray in Scotland by claiming the Lordship of the Isles and occupying Urquhart Castle. Grant regained the castle before 1517, but not before the MacDonalds had driven off 300 cattle and 1,000 sheep, as well as looting the castle of provisions.[25] Grant unsuccessfully attempted to claim damages from MacDonald.[26] James Grant of Freuchie (d.1553) succeeded his father, and in 1544 became involved with Huntly and Clan Fraser in a feud with the Macdonalds of Clanranald, which culminated in the Battle of the Shirts. In retaliation, the MacDonalds and their allies the Camerons attacked and captured Urquhart in 1545.[26] Known as the "Great Raid", this time the MacDonalds succeeded in taking 2,000 cattle, as well as hundreds of other animals, and stripped the castle of its furniture, cannon, and even the gates.[27][28] Grant regained the castle, and was also awarded Cameron lands as recompense.[26]

The Great Raid proved to be the last raid. In 1527, the historian Hector Boece wrote of the "rewinous wallis" of Urquhart,[25] but by the close of the 16th century Urquhart had been rebuilt by the Grants, now a powerful force in the Highlands. Repairs and remodelling continued as late as 1623, although the castle was no longer a favoured residence. In 1644 a mob of Covenanters (Presbyterian agitators) broke into the castle when Lady Mary Grant was staying, robbing her and turning her out for her adherence to Episcopalianism. An inventory taken in 1647 shows the castle virtually empty.[29] When Oliver Cromwell invaded Scotland in 1650, he disregarded Urquhart in favour of building forts at either end of the Great Glen.[29]

When James VII was deposed in the Revolution of 1688, Ludovic Grant of Freuchie sided with William of Orange and garrisoned the castle with 200 of his own soldiers. Though lacking weapons they were well-provisioned and, when a force of 500 Jacobites (supporters of the exiled James) laid siege, the garrison was able to hold out until after the defeat of the main Jacobite force at Cromdale in May 1690. When the soldiers finally left they blew up the gatehouse to prevent the reoccupation of the castle by the Jacobites. Large blocks of collapsed masonry are still visible beside the remains of the gatehouse.[29] Parliament ordered £2,000 compensation to be paid to Grant, but no repairs were undertaken.[30] Subsequent plundering of the stonework and other materials for re-use by locals further reduced the ruins, and the Grant Tower partially collapsed following a storm in 1715.[31]

Later history

[edit]By the 1770s the castle was roofless and was regarded as a romantic ruin by 19th-century painters and visitors to the Highlands.[32] In 1884 the castle came under the control of Caroline, Dowager Countess of Seafield, widow of the 7th Earl of Seafield, on the death of her son the 8th Earl. On Lady Seafield's death in 1911 her will instructed that Urquhart Castle be entrusted into state care, and in October 1913 responsibility for the castle's upkeep was transferred to the Commissioners of His Majesty's Works and Public Buildings.[33] Historic Environment Scotland (formerly Historic Scotland), the successor to the Office of Works, continues to maintain the castle, which is scheduled monument in recognition of its national significance.[2]

In 1994 Historic Scotland proposed the construction of a new visitor centre and car park to alleviate the problems of parking on the main A82 road. Strong local opposition led to a public inquiry, which approved the proposals in 1998.[34] The new building is sunk into the embankment below the road, with provision for parking on the roof of the structure.[35] The visitor centre includes a display of the history of the site, including a series of replicas from the medieval period; a cinema; a restaurant; and a shop. The castle is open all year, and can also host wedding ceremonies.[36] In 2018 518,195 people visited Urquhart Castle, making it Historic Scotland's third most visited site after the castles of Edinburgh and Stirling.[37]

Description

[edit]Urquhart Castle is sited on Strone Point, a triangular promontory on the north-western shore of Loch Ness, and commands the route along this side of the Great Glen as well as the entrance to Glen Urquhart.[38] The castle is quite close to water level, though there are low cliffs along the northeast sides of the promontory. There is considerable room for muster on the inland side, where a "castle-toun" of service buildings would originally have stood, as well as gardens and orchards in the 17th century.[3] Beyond this area the ground rises steeply to the north-west, up to the visitor centre and the A82. A dry moat, 30 metres (98 ft) across at its widest, defends the landward approach, possibly excavated in the early Middle Ages. A stone-built causeway provides access, with a drawbridge formerly crossing the gap at the centre.[38] The castle side of the causeway was formerly walled-in, forming an enclosed space similar to a barbican.[39]

Urquhart is one of the largest castles in Scotland in area.[3] The walled portion of the castle is shaped roughly like a figure-8 aligned northeast-southwest along the bank of the loch, around 150 by 46 metres (492 by 151 ft),[40][13] forming two baileys (enclosures): the Nether Bailey to the north, and the Upper Bailey to the south.[41][42] The curtain walls of both enclosures date largely to the 14th century, though much augmented by later building, particularly to the north where most of the remaining structures are located.[30]

Nether Bailey

[edit]

The 16th-century gatehouse is on the inland side of the Nether Bailey and comprises twin D-plan towers flanking an arched entrance passage. Formerly the passage was defended by a portcullis and a double set of doors, with guard rooms on either side. Over the entrance are a series of rooms which may have served as accommodation for the castle's keeper.[30] Collapsed masonry surrounds the gatehouse, dating from its destruction after 1690.[39]

The Nether Bailey, the main focus of activity in the castle since around 1400,[43] is anchored at its northern tip by the Grant Tower, the main tower house or keep. The tower measures 12 by 11 metres (39 by 36 ft), and has walls up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick.[44] The tower rests on 14th-century foundations, but is largely the result of 16th-century rebuilding.[45] Originally of five storeys, it remains the tallest portion of the castle despite the southern wall collapsing in a storm in the early 18th century. The standing parts of the parapet, remodelled in the 1620s,[45] show that the corners of the tower were topped by corbelled bartizans (turrets).[44] Above the main door on the west, and the postern to the east, are machicolations, narrow slots through which objects could be dropped on attackers. The western door is also protected by its own ditch and drawbridge,[45] accessed from a cobbled "Inner Close" separated from the main bailey by a gate.[46] The surviving interior sections can still be accessed via the circular staircase built into the east wall of the tower. The interior would have comprised a hall on the first floor, with rooms on another two floors above, and attic chambers in the turrets. Rooms on the main floors have large 16th-century windows, though with small pistol holes below to allow for defence.[45]

To the south of the tower is a range of buildings built against the thick, buttressed, 14th-century curtain wall. The great hall occupied the central part of this range, with the lord's private apartments of great chamber and solar in the block to the north, and kitchens to the south.[47] The foundations of a rectangular building stand on a rocky mound within the Nether Bailey, tentatively identified as a chapel.[48]

Upper Bailey

[edit]The Upper Bailey is focused on the rocky mound at the southwest corner of the castle. The highest part of the headland, this mound is the site of the earliest defences at Urquhart. Vitrified material, characteristic of early medieval fortification, was discovered on the slopes of the mound, indicating the site of the early medieval fortification identified by Professor Alcock. In the 13th century, the mound became the motte of the original castle built by the Durwards, and the surviving walls represent a "shell keep" (a hollow enclosure) of this date. These ruins are fragmentary but indicate that there were towers to the north and south of the shell keep.[49]

A 16th-century watergate in the eastern wall of the Upper Bailey gives access to the shore of the loch.[28] The adjacent buildings may have housed the stables.[50] To the south of this, opposite the motte, is the base of a doocot (pigeon house) and the scant remains of 13th-century buildings, possibly once a great hall but more recently re-used as a smithy.[49][51]

Relics

[edit]

After the castle came into public hands repairs and excavations were carried out. These were interrupted by World War I but were resumed and completed by 1922. A large collection of relics was found, including a bronze ewer from the 15th century, coins, jewellery, crosses and other items from the 13th to 17th centuries. The excavations have been criticised for not recording the locations or stratigraphic information, but the collection is of great value, and is now mostly in the care of the National Museum, Edinburgh.[53][54] Samson (1983) has provided a detailed list with illustrations.[54]

References

[edit]- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b Historic Environment Scotland. "Urquhart Castle (SM90309)". Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Tabraham 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 16.

- ^ a b Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 242.

- ^ Anderson, Alan Orr; Anderson, Marjorie Ogilvie (1991). Adomnán's Life of Columba. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 0-19-820215-6.

- ^ Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 251.

- ^ Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 252.

- ^ Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 257.

- ^ Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 265.

- ^ "Fort, Craig Phadrig". Highland Heritage Environment Record. Highland Council. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ "Urquhart Castle: Listed Building (removed)". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b MacGibbon & Ross 1889, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Alcock & Alcock 1992, p. 245.

- ^ a b Tabraham 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Bain (1884), p.239

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Scott, Ronald McNair (1 May 2014). Robert the Bruce: King of Scots. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-86241-172-5.

- ^ a b c Tabraham 2002, p. 32.

- ^ Donald of the Isles and the Earldom of Ross: West-Highland Perspectives on the Battle of Harlaw by Iain G. MacDonald, Paper for Harlaw Remembered, commemorating the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Harlaw, Jun 9, 2011, The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, p. 15-16

- ^ a b Tabraham 2002, p. 34.

- ^ a b Tabraham 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 36.

- ^ MacGibbon & Ross 1889, p. 92.

- ^ a b Tabraham 2002, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Munro, R. W.; Munro, Jean (2004). "Grant family of Freuchie (per. 1485–1622)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73410. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 39.

- ^ a b MacGibbon & Ross (1889), p.93

- ^ a b c Tabraham 2002, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Gifford 1992, p. 217.

- ^ "Urquhart Castle: About the Property". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Cole, Margo (29 March 2001). "Fit for a king". New Civil Engineer.

Local opposition led to a four year delay and a public inquiry, with Wilson's design eventually approved in 1998.

- ^ Cole, Margo (29 March 2001). "Fit for a king". New Civil Engineer.

The agreed location for the visitor centre was within the embankment, with the car parking platform forming the building's roof.

- ^ "Weddings: Urquhart Castle". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b Gifford 1992, p. 216.

- ^ a b Tabraham 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Gifford 1992, p. 217, Gifford names them as "upper bailey" (south) and "nether bailey" (north), but notes a shift in importance from the upper to the nether in the 14th century.

- ^ MacGibbon & Ross 1889, p. 93, MacGibbon & Ross identify the northern enclosure as the "inner" and the southern as the "outer".

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 2, Tabraham follows this later pattern, using "inner close" for the small courtyard by the Grant Tower, "outer close" for the northern enclosure, and "service close" for the southern enclosure.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 8.

- ^ a b MacGibbon & Ross 1889, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Gifford 1992, p. 220.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Gifford 1992, p. 219.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Gifford 1992, p. 221.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Tabraham 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Callander 1924, pp. 180–183.

- ^ Simpson 1964, p. 19.

- ^ a b Samson 1983.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alcock, Leslie; Alcock, Elizabeth A. (1992). "Reconnaissance excavations on Early Historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 1974–84; 5: A, Excavations & other fieldwork at Forteviot, Perthshire, 1981; B, Excavations at Urquhart Castle, Inverness-shire, 1983; C, Excavations at Dunnottar, Kincardineshire, 1984" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 122. Archaeology Data Service: 215–287.

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1884). Calendar of documents relating to Scotland. Vol. II. Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House.

- Bridgland, Nick (2005). Urquhart Castle and the Great Glen. Historic Scotland. London: Batsford. ISBN 9780713487480.

- Callander, J.Graham (1924). "Fourteenth-century Brooches and other Ornaments in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 58: 160–184.

- Gifford, John (1992). Highlands and Islands. The Buildings of Scotland. London: Penguin Books. p. 683. ISBN 0-300-09625-9.

- MacGibbon, David; Ross, Thomas (1889). The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the twelfth to the eighteenth century. Vol. III. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 698.

- Samson, Ross (1983). "Finds from Urquhart Castle in the National Museum, Edinburgh". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 112: 465–476. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- Simpson, William Douglas (1964). Urquhart Castle Official Guide. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Tabraham, Chris (2002). Urquhart Castle. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland. ISBN 1-903570-30-1.