Frank Rutter: Difference between revisions

m move ref info |

→Early life and career: reword - see talk page |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

ISBN 0719054532, ISBN 9780719054532</ref> He railed against the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only one was [[Edgar Degas]]' ''The Ballet from Robert the Devil'' (1876) in the [[Victoria and Albert Museum]].<ref name=taylor/> In 1903 the creation of the [[National Art Collections Fund]] initiated many years of frustration for Rutter, who believed it would siphon off available money from his own aims.<ref name=lago>Lago, Mary. ''Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene'', University of Missouri Press, 1996. ISBN 0826210244, ISBN 9780826210241</ref> |

ISBN 0719054532, ISBN 9780719054532</ref> He railed against the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only one was [[Edgar Degas]]' ''The Ballet from Robert the Devil'' (1876) in the [[Victoria and Albert Museum]].<ref name=taylor/> In 1903 the creation of the [[National Art Collections Fund]] initiated many years of frustration for Rutter, who believed it would siphon off available money from his own aims.<ref name=lago>Lago, Mary. ''Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene'', University of Missouri Press, 1996. ISBN 0826210244, ISBN 9780826210241</ref> |

||

Nevertheless, |

Nevertheless, galvanised by the Impressionist exhibition staged by [[Durand-Ruel]] at the [[Grafton Galleries]] in London in 1905, Rutter used his platform on ''The Sunday Times'' to launch a public subscription, the French Impressionist Fund, which enabled the purchase for £160 of [[Eugène Boudin]]'s ''Entrance to Trouville Harbour''<ref>Variously titled also as ''Port of Trouville'' and ''Harbour at Trouville''.</ref> (1888) as a donation to the nation, although one which the [[National Gallery]] resisted, but accepted in 1906, after Sir Claude Philips and [[D. S. McColl]] had intervened.<ref name=taylor/><ref name=whos/><ref name=odnb/> The fact that Boudin was dead made the gift more palatable than Rutter's original choice of [[Claude Monet]].<ref name=lago/> Rutter's reaction to the work of [[Paul Cézanne]] in the Grafton show was: "What are these funny brown-and-olive landscapes doing in an impressionist exhibition?"<ref name=bullen>Bullen, J. B. ''Post-impressionists in England'', p.3. Routledge, 1988. |

||

ISBN 0415002168, ISBN 9780415002165</ref> |

ISBN 0415002168, ISBN 9780415002165</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:26, 12 August 2008

Francis Vane Phipson Rutter (February 17 1876 – April 18 1937)[1] was a British art critic, curator and activist.

In 1903, he became art critic for The Sunday Times, a position which he held for the rest of his life.[2][3] He was an early champion in England of modern art, founding the French Impressionist Fund in 1905 to buy work for the national collection[4][1], and in 1908 starting the Allied Artists' Association to show "progressive" art,[5] as well as publishing its journal, Art News, the "First Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom".[6] In 1910, he began to actively support women's suffrage, chairing meetings, and giving sanctuary to suffragettes released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act—helping some to leave the country.[7]

From 1912 to 1917, he was the curator of Leeds City Art Gallery.[2] In 1917, he edited the cultural journal, Arts and Letters, with Herbert Read.[8] In his writing after World War I, Rutter observed that advertising imagery was seen by far more people than work in art galleries;[9] he noted a new realism after the period of "abstract experiment";[10] and he praised the work of Dod Proctor as a "complete presentation of twentieth century vision".[11]

Early life and career

Frank Rutter was born at 4 The Cedars, Putney, London, the youngest son of Emmeline Claridge Phipson and Henry Rutter (died 1896), her husband,[12] a solicitor whose hobby was Biblical archaeology and who worked with John Ruskin until an argument ended the arrangement.[2] Rutter was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School, where he studied Hebrew, and in 1896 he went to Queen's College, Cambridge, gaining a degree in Oriental languages after three years.[2] His playing of the banjo made him popular; he wrote some dramatic criticism; he frequently visited, and made friends in, the Latin Quarter in Paris.

He spent a few months as an itinerant tutor, then began as a freelance writer in London with a newly acquired typewriter. One of his successful interviews was with Bernard Shaw on the subject of housing problems—the text of which was entirely provided by Shaw himself. The Times printed an interview with the American scout, Major Burnham, recently returned from South Africa.

He obtained posts as assistant editor of To-day and the Sunday Special, both part of the same publishing group. In February 1901, he became sub-editor of the Daily Mail, and began to write art criticism, mostly for The Financial Times and the The Sunday Times.[2][1] In 1902, he went back to To-day as editor for two years, and for a short time brought it back into profit, until it succumbed to cheaper competition and was merged with London Opinion.[2][1] In 1903, Leonard Rees appointed him art critic of The Sunday Times, a post he held for the rest of his life, 34 years in all.[2][12] Rutter honed his skills whilst doing the job, and also made the acquaintance of leading artists in Paris through frequenting the cafés.[12]

He was a strong supporter of Impressionist and Expressionist Modernism.[13][4] He railed against the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only one was Edgar Degas' The Ballet from Robert the Devil (1876) in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[4] In 1903 the creation of the National Art Collections Fund initiated many years of frustration for Rutter, who believed it would siphon off available money from his own aims.[14]

Nevertheless, galvanised by the Impressionist exhibition staged by Durand-Ruel at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1905, Rutter used his platform on The Sunday Times to launch a public subscription, the French Impressionist Fund, which enabled the purchase for £160 of Eugène Boudin's Entrance to Trouville Harbour[15] (1888) as a donation to the nation, although one which the National Gallery resisted, but accepted in 1906, after Sir Claude Philips and D. S. McColl had intervened.[4][1][12] The fact that Boudin was dead made the gift more palatable than Rutter's original choice of Claude Monet.[14] Rutter's reaction to the work of Paul Cézanne in the Grafton show was: "What are these funny brown-and-olive landscapes doing in an impressionist exhibition?"[16]

Allied Artists' Association

While in Paris in 1907,[12] Rutter had the idea for gaining greater exposure for progressive artists with the Allied Artists' Association (AAA), founded the following year and based on the model of the French Salon des Indépendants with the principle of non-juried shows of international artists, who could subscribe and choose which works they wished to enter (initially five pieces, later three).[5][6]

Rutter was a supporter of the Fitzroy Street Group, which had been founded in 1907, and succeeded in gaining the support of key members, Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, for the AAA. Rutter was a natural organiser and, with the help of Lucien Pissarro attracted 80 members.[17][12] Rutter was keen to mount a foreign section in the first show, and liaised over this with Jan de Holewinski (1871–1927), who was in London to arrange a Russian art and craft show.[5] The first AAA show in July 2008 was in the Royal Albert Hall and had over 3,000 works on display.[12]

In 1909, at the second show in the Royal Albert Hall, over 1,000 works were shown, mainly by British artists, but also the first works (two paintings and twelve woodcuts) exhibited in London by Wassily Kandinsky.[3] Rutter's friends in Leeds, Michael Sadler and his son, Michael Sadleir (who had modified the spelling of his surname) developed a relationship with Kandinsky, who assigned English translation rights for Concerning the Spiritual in Art to Sadleir.[3]

Rutter was secretary of the AAA and organised it for four years. It was artistically accomplished, but not so financially.[12] Through the AAA, Rutter helped many artists, such as Charles Ginner, who, although not achieving outstanding success, was able to gain an audience and develop a loyal following for his work.[18] The AAA exhibited also for the first time in London Constantin Brâncuşi, Jacob Epstein, Robert Bevan and Walter Bayes.[12]

From October 1909 to 1912,[1] Rutter also published and edited the weekly, cheaply-printed Art News, the journal of the AAA, like which it had an open-door policy on contributors, featuring the lectures given to the Royal Academy Schools by Sir William Blake Richmond, as well as Sickert's attack on the Royal Academy, "Straws from Cumberland Market".[6] It was promoted as the "First Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom".[6] Rutter resigned because of financial difficulties.[12]

Women's suffrage, Roger Fry and Leeds

On 30 August 1909 Rutter married Thirz Sarah (Trixie, born 1887/8), whose father, James Henry Tiernan, was a member of the New Zealand Police.[12] With the encouragement of George Bernard Shaw, Rutter became a member of the Fabian Society.[12]

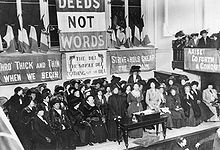

On 12 January 1910, at the Eustace Miles Restaurant, Rutter chaired the meeting of a group which developed into the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement,[7] of which he was the honorary treasurer.[19] Four months later he was the speaker representing the Press at the John Stuart Mill Celebrations, which were staged by the Women's Freedom League.[7]

In 1910, Roger Fry occupied the limelight of avant-garde campaigning for art, when he outraged the public with an exhibition Manet and the post-impressionists at the Grafton Galleries, showcasing work by Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne.[12] Rutter had put the term Post-Impressionist in print in Art News of 15 October 1910, three weeks before Fry's show, during a review of the Salon d'Automne, where he described Othon Friesz as a "post-impressionist leader"; there was also an advert in the journal for the show The Post-Impressionists of France.[20]

Rutter quickly supported Fry's venture with a small book Revolution in Art (enlarged in 1926 as Evolution in Modern Art), its title derived from Gauguin's statement that "in art there are only revolutionists or plagiarists."[12] Rutter wrote in the dedication: "To Rebels of either sex all the world over who in any way are fighting for freedom of any kind I dedicate this study of their painter-comrades."[19]

On 25 March 1911, Rutter chaired a meeting of the Men's Political Union at Caxton Hall, Westminster, and reported that a recent court case at Leeds, in which Alfred Hawkings had been awarded £100 damages for being ejected from a meeting, was "a distinct victory for the suffragist cause." Rutter roused cheers from his listeners upon exhorting them that they needed to prove to their opponents that "the reign of bullying, tyranny, and savagery must come to an end."[21]

In April 1912, Rutter resigned as secretary of the AAA, which had been strongly supported by Lucien Pissarro, Walter Sickert and others, but which he felt was nevertheless dwindling away due to what he condemned as "the incurable snobbishness of the English artist".[2] That year he relocated from London to Leeds for the next five years, having been appointed curator of the Leeds City Art Gallery at a salary of £300 per annum.[4][12] He continued to advocate new ventures in art through his column "Round the galleries" in The Sunday Times.[12]

He used his house at 7 Westfield Terrace, Chapel Allerton, Leeds, to provide accommodation for suffragettes released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act and recovering from hunger strike.[7] In 1913, he provided a character reference so that a job could be obtained in Europe by a "mouse", Elsie Duval; another, Lilian Lenton, a suffragette arsonist also escaped via his home to France in June that year with the aid of his wife.[7][12] Elizabeth Crawford, author of The Women's Suffrage Movement, suggests that other similar events must have taken place, but were kept quiet at the time out of necessity and, later, due to Rutter's taciturnity.[7] He wrote in an epilogue to his autobiogaphy:

- the only furiously active part of my life was the few years during which I was connected with the militant suffrage movement and of this I have said nothing, because if I once began I should want to fill a volume with my experiences during this exciting time. It is all over now, the battle has been won, and this is not the place in which to recount the skirmishes in which I had the honour to take part."[7]

He did not agree with the later, more extreme tactics of the WSPU leaders, who nevertheless still commanded his respect and admiration.[7] He encouraged the artist, Emily Susan Ford (1850-1930), Vice-Chairman of the Artists' Suffrage League and exhibited her work in the Leeds gallery.[22]

Rutter initially had plans to create a modern art collection at the Leeds gallery, but had been frustrated in this aim by "boorish" local councillors; his association with the escape of Lilian Lenton had further damaged his standing.[12] Before he left the city, he co-founded the Leeds Art Collections Fund with Michael Sadler, who was the vice-chancellor of Leeds University and a collector of work by Kandinsky and Gauguin.[12] The Fund helped with acquisitions and shows, among them the first major John Constable show and another in June 1913 of Post-Impressionism held at the Leeds Arts Club, which had been started by Holbrook Jackson and A.R. Orage, editor of The New Age, and was galvanised by the new activity.[12] The discussions there about contemporary art had a significant influence on the thinking of Herbert Read (1893–1968),[12] who was introduced to modern art by Rutter.[23] Rutter's plan for a literary version of the AAA had a strong appeal for Read.[12]

Through World War I and Arts and Letters

In October 1913, Rutter was commissioned by the Doré Gallery in Bond Street in the West End to curate the Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, which displayed the story of those movements from Camille Pissarro to Vorticist Wyndham Lewis (who was no longer on good terms with Fry).[12] Rutter's consummate curation and catalogue foreword were a testament to his deep knowledge of the subject.[12]

He praised Nevinson's The Departure of the Train De Luxe as "the first English Futurist picture".[24] Also in 1913, The Cabyard, Night, the only painting by Robert Bevan (1865–1925) acquired for a public collection during the artist's lifetime, was bought by the Contemporary Art Society on Rutter's recommendation that they should obtain it for the nation before a more discerning collector bought it.[25]

Rutter, along with Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner had planned the launch of a journal, Arts and Letters, for Spring 1914, but this was delayed by the outbreak of war.[26][6] It began publication in 1917, co-edited by Rutter and Herbert Read,[27] whose aesthetic and critical ideas dominated.[6][8] It was a modernist magazine of visual and literary art, which fused the artistic and the political,[23] One of the pieces printed was Sickert's "Thérèse Lassore" in 1918, when the journal ceased publication for a year. It resumed again with Osbert Sitwell as Rutter's co-editor—and T.S. Eliot's theories predominating editorially—but folded in 1920.[8]

From 1915 to 1919, Rutter returned to the Allied Artists' Association in the guiding role of chairman.[12][28] In 1917, he resigned his job at the Leeds City Art Gallery,[12] and he worked for the Admiralty until 1919,[1] when he opened the Adelphi Gallery to exhibit small pieces by Ginner, Edward Wadsworth an David Bomberg.[12] Finding this a restriction on his "liberty and leisure" he returned to writing and completed in the region of 20 books, as well as a considerable number of contributions The Burlington Magazine, Apollo, Studio Magazine, The Financial Times and The Times.[12]

1920s and 1930s

Rutter in his inter-war writings emphasised both the spiritual and social role of art.[23] He also commented on the visual power to be found in the London Underground: "The whole nation is much less affected by what pictures are shown in the Royal Academy than by what posters are put up on the hoardings[29]. A few thousand see the first, but the second are seen by millions. The art galleries of the People are not in Bond Street but are to be found in every railway station."[30]

On 28 March 1920 in The Sunday Times, Rutter reviewed the short-lived Group X (a reforming of the Vorticists), "the real tendency of the exhibition is towards a new sort of realism, evolved by artists who have passed through a phase of abstract experiment.".[10]

He divorced his wife around this time, and on 29 March 1920 married Ethel Dorothy (born 1894/5), the second daughter of William Robert Bunce, a coal merchant.[12]

In 1927, he said of Newlyn artist Dod Proctor's painting, Morning, exhibited in the Royal Academy that it was "a new vision of the human figure which amounts to the invention of a twentieth century style in portraiture"[31] and "She has achieved apparently with consummate ease that complete presentation of twentieth century vision in terms of plastic design after which Derain and other much praised French painters have been groping for years past."[11]

1928–1931, Rutter was European Editor of International Studio, New York.[1] He was also the London Correspondent for the Association Française d’Expansion et d’Echanges Artistiques.[1] In 1932, he praised advances in the Tate Gallery's attitude towards art since its foundation (although others, notably Douglas Cooper, considered it "hopelessly insular").[32]

Death

He had suffered from a bronchial complaint for a number of years, as a result of which he periodically sojourned on the South Coast, visiting London exhibitions when he felt in good enough health to do so.[2] In April 1937, he had an attack of bronchitis and died a fortnight later at age 61 in his home at 5 Litchfield Way, Golders Green, London. He wrote his Sunday Times article up to a week before his death.[2] He left his estate, which included around 80 paintings by the likes of Gilman, Ginner, Gore and Lucien Pissarro, to his wife.[12] He had no children.[2] He was buried at Hampstead on 21 April 1937.[12]

Books

- Varsity Types, 1902

- The Path to Paris, 1908

- Rossetti, Painter and Man of Letters, 1909

- Whistler, a Biography and an Estimate, 1910

- Revolution in Art, 1910

- The Wallace Collection, 1913

- Some Contemporary Artists, 1922

- The Poetry of Architecture, 1923

- Richard Wilson and Farington, 1923

- The Old Masters, 1925

- Evolution in Modern Art, 1926

- Theodore Roussel, 1927

- Since I was Twenty-Five, 1928

- El Greco, 1930

- Art in My Time, 1933

- Modern Masterpieces, 1936

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Rutter, Frank V. P.", Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007. Retrieved from ukwhoswho 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k The Times, 19 April 1937, p.16, issue 47662, col B, "Obituary: Mr. Frank Rutter". Retrieved from infotrac.galegroup.com, 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Glew, Adrian. "Every work of art is the child of its time", TATE ETC., issue 7, Summer 2006. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Brandon. Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747-2001, p.134, Manchester University Press, 1999. ISBN 0719054532, ISBN 9780719054532

- ^ a b c "Allied Artists’ Association (A.A.A.)", Grove Art Online, retrieved from Oxford Art Online (subscription site), 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Sickert, Richard Walter; Robins, Anna Gruetzner. Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, p.xxxi, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0199261695, ISBN 9780199261697. Retrieved from Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crawford, Elizabeth. The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866-1928, p.612, Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415239265, ISBN 9780415239264

- ^ a b c Aldington, Richard; H.D. (Doolittle, Hilda); Zilboorg, Caroline. Richard Aldington & H.D.: Their Lives in Letters, p.157, Manchester University Press, 2003. ISBN 0719059720, ISBN 9780719059728.

- ^ Saler, pp.101-102.

- ^ a b "Group X", Grove Art Online, retrieved from Oxford Art Online (subscription site), 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b Lang, Elsie M. British Women in the Twentieth Century, Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766161153, ISBN 9780766161153

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Owen, Felicity (article credit). "Rutter, Francis Vane Phipson", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required). Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ^ Flint, Kate. Impressionists in England: The Critical Reception, p.33, Routledge.ISBN 0710094701, ISBN 9780710094704.

- ^ a b Lago, Mary. Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene, University of Missouri Press, 1996. ISBN 0826210244, ISBN 9780826210241

- ^ Variously titled also as Port of Trouville and Harbour at Trouville.

- ^ Bullen, J. B. Post-impressionists in England, p.3. Routledge, 1988. ISBN 0415002168, ISBN 9780415002165

- ^ Glew states 40 members.

- ^ The Times, 7 January 1952, p.6, Issue 52202, col E, "Mr. Charles Ginner". Retrieved from infotrac.galegroup.com, 8 August 2008.

- ^ a b Bryson, Norman; Holly, Ann Michael; Moxey, Keith P. F. Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations, p.42. Wesleyan University Press, 1994. ISBN 081956267X, ISBN 9780819562678. Retrieved from Google books.

- ^ Bullen, p.37

- ^ The Times, 27 March 1911, p. 6, issue 39543, col F, "Woman Suffrage. The Interruption Of Public Meetings." Retrieved from infotrac.galegroup.com, 8 August 2008.

- ^ Crawford, pp.225-226

- ^ a b c Saler, Michael T. The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground, p.52, Oxford University Press US, 1999. ISBN 0195119665, ISBN 9780195119664.

- ^ Walsh, Michael. Apollo, February 2005, "Vital English art: futurism and the vortex of London 1910-14". Retrieved from findarticles.com, 8 August 2008.

- ^ "Art catalogue: Robert Bevan (1865-1925)", Brighton and Hove Museums. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ Robins gives Gilman's death in 1917 as contributory to the publication delay. However, Gilman died in 1919 (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).

- ^ Aldington gives Ginner and Gilman as co-editors with Rutter.

- ^ Who Was Who says he returned to the AAA 1915–1922.

- ^ British English for billboard

- ^ Saler, pp.101-102.

- ^ King, Averil. Apollo, "An exotic awakening", 1 January 2006. Retrieved from findarticles.com (registration required), 8 August 2008.

- ^ Spalding, Frances (1998). The Tate: A History, pp. 65–66. Tate Gallery Publishing, London. ISBN 1 85437 231 9.