Morea: Difference between revisions

m Date maintenance tags and general fixes |

m →Origins of the name: Corrected a misspelling of the name Fallermayer and removed "a since discredited theory" since it is not reflected with proof and a reliable source. |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Popular belief in Greece today is that the name originates from the word ''moria'', meaning mulberry, a common plant in the region, used in the production of silk for which the Peloponnese was famous. The peninsula itself resembles the shape of a red mulberry leaf, which is very similarly shaped. In Greece some believe that this name may be of Frankish origin even though Frankish municipalities appeared here only in the 13th century. |

Popular belief in Greece today is that the name originates from the word ''moria'', meaning mulberry, a common plant in the region, used in the production of silk for which the Peloponnese was famous. The peninsula itself resembles the shape of a red mulberry leaf, which is very similarly shaped. In Greece some believe that this name may be of Frankish origin even though Frankish municipalities appeared here only in the 13th century. |

||

In 1830, the Austrian historian [[Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer]] (1790–1861) published the first of his volumes ''Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea während des Mittelalters'' ("History of the Morea Peninsula during the Middle Ages"). Based on his analysis of the spread of Slavic place names in mainland Greece, |

In 1830, the Austrian historian [[Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer]] (1790–1861) published the first of his volumes ''Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea während des Mittelalters'' ("History of the Morea Peninsula during the Middle Ages"). Based on his analysis of the spread of Slavic place names in mainland Greece, Fallermayer proposed that the 19th century Greeks had almost no linear cultural connection to the ancients but a large one to the [[Slavic peoples|Slavic tribes]] who had invaded during the 6th and 7th centuries. To support his thesis, Fallmerayer proposed that the word comes from the [[Slavic languages|Slavic word]] ''more'', meaning ''sea'' which suggested that the Slavs reached the Mediterranean basin. Fallmerayer did find some evidence in the form of several scattered village names as well as the presence of a strong "ω" sound. Morias in the Ottoman period showed very little trace of Slavonic influence, with no dialects and only 2 Slavonic Churches in the whole peninsula. Discredit to "Morea" includes the fact that Slavic toponyms of the region are largely in the central and north areas which are desolate and mounatinous, with little connection to the sea. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 01:37, 25 September 2009

The Morea (Greek: Μωρέας or Μωριάς, Arvanitika: More, French: Morée, Italian: Morea, Turkish: Mora) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. It also referred to a Byzantine province in the region, known as the Despotate of Morea.

Origins of the name

This section possibly contains original research. (September 2009) |

There is some uncertainty over the origin of the name "Morea", which is first recorded only in the 10th century in the Byzantine chronicles.

Popular belief in Greece today is that the name originates from the word moria, meaning mulberry, a common plant in the region, used in the production of silk for which the Peloponnese was famous. The peninsula itself resembles the shape of a red mulberry leaf, which is very similarly shaped. In Greece some believe that this name may be of Frankish origin even though Frankish municipalities appeared here only in the 13th century.

In 1830, the Austrian historian Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer (1790–1861) published the first of his volumes Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea während des Mittelalters ("History of the Morea Peninsula during the Middle Ages"). Based on his analysis of the spread of Slavic place names in mainland Greece, Fallermayer proposed that the 19th century Greeks had almost no linear cultural connection to the ancients but a large one to the Slavic tribes who had invaded during the 6th and 7th centuries. To support his thesis, Fallmerayer proposed that the word comes from the Slavic word more, meaning sea which suggested that the Slavs reached the Mediterranean basin. Fallmerayer did find some evidence in the form of several scattered village names as well as the presence of a strong "ω" sound. Morias in the Ottoman period showed very little trace of Slavonic influence, with no dialects and only 2 Slavonic Churches in the whole peninsula. Discredit to "Morea" includes the fact that Slavic toponyms of the region are largely in the central and north areas which are desolate and mounatinous, with little connection to the sea.

History

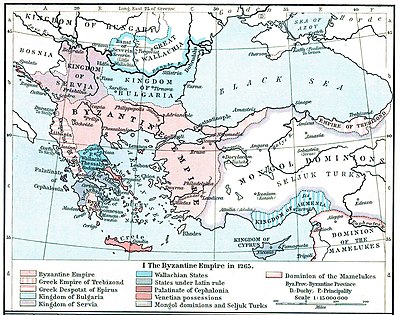

After the conquest of Constantinople by the forces of the Fourth Crusade (1204), two groups of Franks undertook the occupation of the Morea. They created the Principality of Achaea, a largely Greek-inhabited statelet ruled by a Latin (Western) autocrat. In referring to the Peloponnese, they followed local practice and used the name "Morea".

The most important prince in the Morea was Guillaume II de Villehardouin (1246–1278), who fortified Mistra (Mystras) near the site of Sparta in 1249. After losing the Battle of Pelagonia (1259) against the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, Guillaume was forced to ransom himself by giving up most of the eastern part of Morea and his newly built strongholds.

In the mid-14th century, the later Byzantine Emperor John VI Cantacuzenus reorganized Morea into the Despotate of the Morea, usually ruled from Mistra by the current heirs of the emperor. The Byzantines eventually recovered the remainder of the Frankish part of the Morea, but in 1460 the peninsula was overrun and conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

The peninsula was captured for the Republic of Venice by Francesco Morosini during the Morean War of 1684-99. Venetian rule proved unpopular, and the Ottomans recaptured the Morea in a lightning campaign in 1714. Under renewed Ottoman rule, centered at Tripolitsa, the region enjoyed relative prosperity, but the latter 18th century was marked by renewed dissatisfaction. The brutal repression of the Orlov Revolt did not hinder the emergence of the armed bands of the klephts, which waged a virtual guerrilla war with the Turks, aided both by the decay of Ottoman power and the re-emergence of Greek national consciousness. Ultimately, the Moreas would form the cradle and centre of the Greek Revolution.

Chronicle of Morea

The anonymous 14th century Chronicle of Morea in more than 9,000 lines of political verse, relates events of the establishment of feudalism in mainland Greece by the Franks following the Fourth Crusade. The Chronicle is famous in spite of its historical unreliability because of its lively description of life in the feudal community and because of the character of the language which reflects the rapid transition from Medieval to Modern Greek. The Chronicle, written in French, survives in two parallel Greek texts, the Ms Havniensis 57 (14th–15th century, in Copenhagen) and the Ms Parisinus graecus 2898 (15th–16th century, at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris), and the difference of about one century shows a considerable number of linguistic differences due to the rapid evolution of the Greek language.

See also

References

- Crusaders as Conquerors: the Chronicle of Morea, translated from the Greek with notes and introduction by Harold E. Lurier, Columbia University, 1964.

External links

- Mystras: illustrated capsule history

- Mystra: history