The Author's Farce: Difference between revisions

NocturneNoir (talk | contribs) →Sources: rm |

NocturneNoir (talk | contribs) →Critical response: cuts |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

==Critical response== |

==Critical response== |

||

The success of ''The Author's Farce'' established Fielding as a London playwright.<ref>Rivero 1989 p. 31</ref> |

The success of ''The Author's Farce'' established Fielding as a London playwright.<ref>Rivero 1989 p. 31</ref> The 2 May edition of the ''Daily Post'' reported that the play received universal approval and, on 6 May, reported that seats were in great demand. The 7 May 1730 issue of the ''[[Grub Street Journal]]'' noted that the play was popular among "Persons of Quality"; many notable persons went to see the show, including [[John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont]] on the first night and [[Frederick, Prince of Wales]], whose attendance was mentioned in the 28 April 1730 ''London Evening Post'' and the 15 May 1730 ''Daily Post''.<ref>Fielding 2004 pp. 194–195</ref> The only surviving comments from any of those who saw the play come from the diary of the Earl of Egmont. He reported that ''The Author's Farce'' and ''Tom Thumb'' "are a ridicule on poets, several of their works, as also of operas, etc., and the last of our modern tragedians, and are exceedingly full of humour, with some wit."<ref>Fielding 2004 qtd p. 204</ref> |

||

Except for a few minor references, there is very little further mention of the play during the 18th century. The 19th century mostly followed the same trend; only three scenes were included in Alfred Howard's ''The Beauties of Fielding'', which collected passages from Fielding's works. A chapter on the play is included in Frederick Lawrence's ''Life of Fielding'' (1855), and it is mentioned by [[Leslie Stephen]] and [[Henry Austin Dobson|Austin Dobson]] |

Except for a few minor references, there is very little further mention of the play during the 18th century. The 19th century mostly followed the same trend; only three scenes were included in Alfred Howard's ''The Beauties of Fielding'', which collected passages from Fielding's works. A chapter on the play is included in Frederick Lawrence's ''Life of Fielding'' (1855), and it is mentioned by [[Leslie Stephen]] and [[Henry Austin Dobson|Austin Dobson]], who focus on what the play says about Grub Street and Fielding. George Saintsbury included ''The Author's Farce'' and two other plays in a Fielding collected edition of 1893, but ignored the others.<ref>Fielding 2004 pp. 205–206</ref> |

||

Most later critics agreed with Dobson that the play primarily provides a commentary on events in Fielding's life, and marks Fielding's move from older forms of comedy to the new satire of his contemporaries.<ref>Lockwood 2004 p. 206</ref> [[Wilbur Lucius Cross]], in 1918, believed the play revealed |

Most later critics agreed with Dobson that the play primarily provides a commentary on events in Fielding's life, and marks Fielding's move from older forms of comedy to the new satire of his contemporaries.<ref>Lockwood 2004 p. 206</ref> [[Wilbur Lucius Cross]], in 1918, believed the play revealed Fielding's farcical and burlesque talent and not regular drama.<ref>Cross 1918 p. 80</ref> In 1963, [[F. W. Bateson]] included the play in a list of "satirical extravaganzas."<ref>Bateson 1963 pp. 121–126</ref> [[Frederick Homes Dudden]], writing in 1966, was clear that the revised version was undoubtedly an improvement on the original,<ref>Dudden 1966 p. 50</ref> and that the puppet show in the third act "is a highly original satire on the theatrical and quasi-theatrical amusements of the day."<ref>Dudden 1966 p. 54</ref> In the same year, Charles Woods argued that ''The Author's Farce'' was an integral part of Fielding's career.<ref>Woods 1966 p. XV</ref> |

||

Comments made by Woods in the introduction to his edition of ''The Author's Farce'' influenced later critical interpretations of the play. Woods dismisses a political reading of the work, and emphasizes instead how it affected Fielding's career as a playwright.<ref>Lockwood 2004 p. 207</ref> Ian Donaldson claimed in 1970 that "''The Author's Farce'', like Fielding's other dramatic burlesques, turns out finally to be a good-natured romp."<ref>Donaldson 1970 p. 194</ref> In his 1975 comparison of Fielding's theatrical style and form, J. Paul Hunter argues that "Many of the literary and theatrical jibes are witty, but often the method seems essentially untheatrical in its slow timing and its failure to use dramatic conflict, as if Fielding were so anxious to comment directly that he gave little attention to setting up an occasion. Fielding's defense would surely have been that he intended to parody the bad theater of his contemporaries, and the defense is, in a sense, unanswerable, for the play leaves open the question of whether Fielding is responsible or Luckless is."<ref>Hunter 1975 p. 53</ref> Later in 1979, Pat Rogers declares, "Few livelier theatrical occasions can ever have been seen than the original runs of ''The Author's Farce'', with their mixture of broad comedy, personal satire, tuneful scenes and rapid action."<ref>Rogers 1979 p. 49</ref> |

Comments made by Woods in the introduction to his edition of ''The Author's Farce'' influenced later critical interpretations of the play. Woods dismisses a political reading of the work, and emphasizes instead how it affected Fielding's career as a playwright.<ref>Lockwood 2004 p. 207</ref> Ian Donaldson claimed in 1970 that "''The Author's Farce'', like Fielding's other dramatic burlesques, turns out finally to be a good-natured romp."<ref>Donaldson 1970 p. 194</ref> In his 1975 comparison of Fielding's theatrical style and form, J. Paul Hunter argues that "Many of the literary and theatrical jibes are witty, but often the method seems essentially untheatrical in its slow timing and its failure to use dramatic conflict, as if Fielding were so anxious to comment directly that he gave little attention to setting up an occasion. Fielding's defense would surely have been that he intended to parody the bad theater of his contemporaries, and the defense is, in a sense, unanswerable, for the play leaves open the question of whether Fielding is responsible or Luckless is."<ref>Hunter 1975 p. 53</ref> Later in 1979, Pat Rogers declares, "Few livelier theatrical occasions can ever have been seen than the original runs of ''The Author's Farce'', with their mixture of broad comedy, personal satire, tuneful scenes and rapid action."<ref>Rogers 1979 p. 49</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:15, 16 August 2010

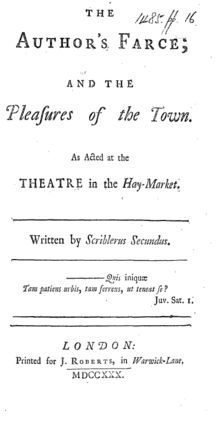

The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town is a play by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding, first performed on 30 March 1730 at the Little Theatre, Haymarket. Written in response to the Theatre Royal's rejection of his earlier plays, The Author's Farce was Fielding's first theatrical success. The Little Theatre allowed Fielding the freedom to experiment, and to alter the traditional comedy genre.

The first and second acts describe Harry Luckless's attempts to woo his landlady's daughter, and his efforts to make money by writing plays. In the second act, he finishes a puppet theatre play titled The Pleasures of the Town, about the Goddess Nonsense's choice of a husband from allegorical representatives of theatre and other literary genres. After its rejection by one theatre, Luckless's play is staged at another. The third act becomes a play within a play, in which the characters in the puppet play are portrayed by humans. The Author's Farce ends with a merging of the play's and the puppet show's realities.

The play established Fielding as a popular London playwright. His play within a play satirized the way in which the London theatre scene, in his view, abused the literary public by offering new and inferior genres. The Author's Farce is now considered a critical success, although it was largely ignored by critics until the 20th century.

Plot

Most of Fielding's plays were written in five acts, but The Author's Farce was written in three. The opening introduces the main character, Harry Luckless, and his attempts to woo Harriot, the daughter of his landlady Mrs Moneywood. The play begins in much the same way as Fielding's earlier romance-themed comedies, but it quickly becomes a different type of play, mocking the literary and theatrical establishment.[1] Luckless is trying to become a successful writer, but without the income that would allow him to focus on his writing. Although others try to support him financially, Luckless refuses their help; when his friend, Witmore, pays his rent behind his back, Luckless steals the money from Mrs Moneywood. By the second act, Luckless is seeking assistance to help finish his play, The Pleasures of the Town, but he receives poor advice, and the work is rejected by the local theatre. After revising his play, Luckless finds another willing to put on his show.[2] This leads to the third act, in which Luckless puts on his play as a puppet show, but with actors taking the place of the puppets.[3]

The third act is dominated by the puppet show, which functions as a play within the play. At the start, the Goddess of Nonsense chooses a mate from a series of suitors along the River Styx. These suitors, all dunces, include Dr Orator, Sir Farcical Comic, Mrs Novel, Bookseller, Poet, Monsieur Pantomime, Don Tragedio, and Signior Opera.[4] She eventually chooses Signior Opera, a foreign, castrato opera singer, as her favourite, after he sings an aria about money. In response, Mrs Novel claims that she loved Signior Opera, and died giving birth to his child.[5] At this revelation, the goddess becomes upset, but she is quick to forgive.[4] The play within the play is interrupted by Constable and Murdertext, two characters who have come to arrest Luckless "for abusing Nonsense",[6] but Mrs Novel persuades Murdertext to let the play finish. Someone from the land of Bantam then arrives to tell Luckless that he is the prince of Bantam. News follows that the King of Bantam has died, and that Luckless is to be made the new king. The play concludes with a final twist: it is revealed that Luckless's landlady is really the Queen of "Old Brentford" and that her daughter, Harriot, is now royalty.[7] The play concludes with an epilogue in which four poets discuss how it should end, until a cat, in the form of a woman, takes over and brings the performance to a close.[8]

Themes

Fielding uses Luckless and The Author's Farce to portray aspects of his own life and experience with the London theatre community,[9] and the plot serves as revenge for the rejection of Fielding's previous play.[10] However, Fielding's rejection by the Theatre Royal and his being forced into minor theatres proved beneficial, because it allowed him more freedom to experiment with his plays in ways that would have been unacceptable at larger locations. This experimentation, beginning with The Author's Farce,[11] is an attempt by Fielding to try writing in formats beyond the standard five-act comedy play. Though he returned to writing five-act plays later, many of his plays contain plot structures that differed from those common to contemporary plays. To distinguish his satirical intent, Fielding claims that the work was written by "Scriblerus Secundus," which places his play within an earlier literary tradition. The name refers to the Scriblerus Club, a satirical group whose members included Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot.[12] Fielding's use of the pseudonym connects his play to the satirical writings of the Scriblerus Club's members, and reveals their influence on his new style,[13] such as incorporating in their work the styles of the entertainments that they were ridiculing. Fielding thus allows the audience to believe that he is poking fun at others, less discriminating than themselves, and less able to distinguish good art from bad.[14] Fielding also borrowed characters from the work of the Club's members, such as the Goddess of Nonsense, influenced by Pope's character from The Dunciad, Dulness, who is at war with reason.[15] Nonsense, like Dulness, is a force that promotes the corruption of literature and taste, to which Fielding adds a sexual element. This sexuality is complicated, yet also made comical, when Nonsense chooses a castrated man as her mate. Her choice emphasises a lack of morality, one of the problems that Fielding believed dominated 18th-century British society.[16] Despite the link to Dulness, the general satire of the play more closely resembles Gay's Beggar's Opera than the other works produced by the Scriblerus Club.[17]

The Author's Farce is not a standard comedy, rather it is a farce, and as such employs petty forms of humour like slapstick. Instead of relying on rhetorical wit, Fielding incorporates dramatic incongruities. For example, actors play puppets in a life-size version of a puppet play. Fielding's purpose in relying on the farce tradition was specifically to criticize society as a whole.[18] Like others, Fielding believed that there was a decline in popular theatre related to the expansion of the its audience, therefore he satirises it, its audiences, and its writers throughout The Author's Farce.[19] Speaking of popular entertainment in London, Fielding's character Luckless claims, "If you must write, write nonsense, write operas, write entertainments, write Hurlothrumbos, set up an Oratory and preach nonsense, and you may meet with encouragement enough."[20] Luckless's only ambition is to become successful. Many of the characters in the play believe that the substance of a play matters little as long as it can earn a profit. Harriot believes that the only important characteristic of a lover is his merit, which, to her, is his ability to become financially successful.[21] Fielding later continues this line of attacks on audiences, morality, and genres when he criticises Samuel Richardson's epistolary novel Pamela, in which a nobleman makes advances upon a servant-maid with the intent of making her his mistress.[22]

The blending of the fictional and real worlds at the end of the play represents the inability of individuals to distinguish between fictional and real experience.[23] The final act of the play also serves as Fielding's defence of traditional hierarchical views of literature. He satirizes new literary genres with low standards by using personified versions of them during the puppet show.[24] In particular, Fielding mocks how contemporary audiences favoured Italian opera,[25] a dramatic form that he regarded with contempt. Fielding considered it "a foreign intruder that has weaned the public from their native entertainments".[26] The character Signior Opera, the image of the favoured castrato singer within the puppet show, is a parody of the foreigners who performed as singers, along with the audiences that accepted them. Additionally, the character also serves as a source of humour that targets 18th-century literary genres; after the character Nonsense chooses the castrato Signior Opera as her husband, Mrs Novel objects, declaring that she gave birth to his child. This act would be physically impossible because Opera is a castrato, and it pokes fun at how the genres and the public treated such individuals. Fielding was not alone in using the castrato image for humour and satire; William Hogarth connects the castrato singer with politics and social problems,[27] and many other contemporary works mock women who favour eunuchs.[28]

Sources

Fielding drew many aspects of the play from his own experience.[10] During Act II, the characters Marplay and Sparkish, two theatre managers, offer poor advice to Luckless on how to improve his play, and then reject it. This fictional event mirrors Fielding's own life when Colley Cibber and Robert Wilks of the Theatre Royal rejected The Temple Beau. Cibber was a source for the character of Marplay and Wilks for Sparkish, but this was altered when Wilks died; the revised version of 1734, after Wilks's death, does not include Sparkish. In his place, Fielding introduces a character that mocks Theophilus Cibber, the son of Colley, and his role in the Actor Rebellion of 1733.[29] Another biographical parallel involves the relationship between Luckless and Mrs Moneywood, which is similar to Fielding's own relationship with Jan Oson, his landlord while staying at Leiden in early 1729. While there, Fielding managed to incur a debt of approximately £13 (equivalent to about £1,760 as of 2008),[nb 1] and a legal case was brought against him. He abandoned Leiden along with his personal property and fled to London. Oson seized Fielding's property, a parallel to Mrs Moneywood's threats to seize Luckless's possessions.[31] Other characters are modelled on well-known personalities who Fielding was aware of but were not directly connected to his life: Mrs Novel is Eliza Haywood, a writer, actress, and publisher, Signior Opera is Senesino, a famous Italian contralto castrato,[32] Bookweight is similar to Edmund Curll, a bookseller and publisher known for unscrupulous publication and publicity,[33] Orator is John Henley, a clergyman, entertainer, and well-known orator, Monsieur Pantomime is John Rich, a director and theatre manager, and Don Tragedio is Lewis Theobald, an editor and author. Sir Farcical Comick is another version of Colley Cibber, but only in his role as an entertainer.[34]

Although elements of the play are similar to aspects of Fielding's life, he also drew from many literary sources and traditions. There is a strong similarity between the structure and plot of The Author's Farce and those of George Farquhar's Love and a Bottle (1698) in that both plays describe the relationship between an author and his landlady. However, the plays only deal with the same generalized idea and the particulars of each are different.[35] Also, Fielding drew on the Scriblerus Club's use of satire and the humour common to traditional Restoration and Augustan drama. In addition, many of Luckless's situations are similar to those found within various traditional British dramas, including John Dryden's The Rehearsal (1672), a satirical play about staging a play. It is possible that Pope's Dunciad Variorum, published on 13 March 1729, influenced the themes of the play and the plot of the puppet show. However, the Scriblerus Club style of humour as a whole influences The Author's Farce and it is possible that Fielding borrowed from Gay's Three Hours after Marriage (1717) and The Beggar's Opera (1728).[36] Conversely, Fielding's play influenced later Scriblerus Club works, especially Pope's fourth book of his revised Dunciad and possibly Gay's The Rehearsal at Goatham.[37]

Performance history

The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town was written during 1729 in response to the rejection by the Theatre Royal of Fielding's earlier plays.[35] The 18 March 1730 Daily Post and the 21 March 1730 Weekly Medley and Literary Journal ran notices stating that the play was in rehearsal. Soon after, the Daily Post advertised the premiere of The Author's Farce in its 23 and 26 March editions, noting that the play would contain a puppet show. The advertisement mentioned restricted seating and high ticket prices, suggesting much public interest in viewing the play was anticipated. The play opened on Easter Monday, 30 March 1730, at the Little Theatre, Haymarket, and ran for 41 performances, eight of them in the three weeks after Easter. On 6 April 1730, it was billed alongside The Cheats of Scapin, and later the last act was made into the companion piece to Hurlothrumbo for one show.[38]

Fielding altered and rewrote The Author's Farce for its run beginning on 21 April 1730, when it shared the bill with his earlier play Tom Thumb. This combination continued through May and June for a total of 32 performances, and was later billed for a revival on 3 July 1730. Starting on 1 August 1730, the third act of the The Author's Farce was revived by the Little Theatre during the week of the Tottenham Court fair. The next mention of the play appeared in 17 October 1730 when the Daily Post advertised a new prologue to be added to The Author's Farce. This altered version of the play was performed on 21 October and was followed by a version without the prologue, which was put on for one more night before being replaced with The Beggar's Wedding by Charles Coffey. There were four performances after The Author's Farce was revived on 18 November 1730 and four more starting on 4 January 1731. Between November and January, only the first two acts of the play were shown, and it was paired with the afterpiece Damon and Phillida; however, Damon and Phillida was replaced by The Jealous Taylor on 13 January 1731. There was another performance on 3 February 1731 and more followed in March. Productions in 1732 included a new prologue, now lost, that had been added for the 10 May 1731 showing.[39]

Starting on 31 March 1731, The Author's Farce was paired with the Tom Thumb remake, The Tragedy of Tragedies, for six performances as a replacement for The Letter Writers, the original companion piece. Although both Tragedy of Tragedies and The Author's Farce were main shows, they were alternated on the billing until the 18 June 1731 performance, which was the final showing of any Fielding play in the Little Theatre except for a 12 May 1732 benefit show of The Author's Farce. The last documented non-puppet version was performed on 28 March 1748 by Theophilus Cibber as a two-act companion piece for a benefit show. The Pleasures of the Town act was performed as a one-act play outside London throughout the century, including a show in Norwich during 1749, 15 shows at Norwich during the 1750s, and a production at York during the 1751–52 theatre season. Additionally, there were benefit shows, including the third act, as far away as Dublin, on 19 December 1763 and Edinburgh during 1763.[40] There were many performances of the puppet theatre versions, including a travelling show by Thomas Yeates, titled Punch's Oratory, or The Pleasures of the Town, that started in 1734.[41]

In response to the Actor Rebellion of 1733, Fielding produced a revised version of The Author's Farce, incorporating a new prologue and epilogue. Performed at the Theatre Royal, it was advertised in the 8 January 1734 edition of the Daily Journal, and was shown for six nights, opening with an inferior replacement cast for some of the important characters. It was joined by The Intriguing Chambermaid for four nights and The Harlot's Progress for two. These six occasions were the only performances of the revised version, which was printed together with The Intriguing Chambermade (1734) and included a letter by an unknown writer, possibly Fielding himself.[42] The 1734 edition of the play was printed in 1750, and it was used for all later publications until 1966.[35] Printed texts of the play were included in Arthur Murphy's 1762 Works of Henry Fielding and George Saintsbury's 1893 Works of Henry Fielding. The latter includes The Author's Farce along with only two other plays. The 1903 Works of Henry Fielding, edited by G. H. Maynadier, included only the first two acts.[43]

Critical response

The success of The Author's Farce established Fielding as a London playwright.[44] The 2 May edition of the Daily Post reported that the play received universal approval and, on 6 May, reported that seats were in great demand. The 7 May 1730 issue of the Grub Street Journal noted that the play was popular among "Persons of Quality"; many notable persons went to see the show, including John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont on the first night and Frederick, Prince of Wales, whose attendance was mentioned in the 28 April 1730 London Evening Post and the 15 May 1730 Daily Post.[45] The only surviving comments from any of those who saw the play come from the diary of the Earl of Egmont. He reported that The Author's Farce and Tom Thumb "are a ridicule on poets, several of their works, as also of operas, etc., and the last of our modern tragedians, and are exceedingly full of humour, with some wit."[46]

Except for a few minor references, there is very little further mention of the play during the 18th century. The 19th century mostly followed the same trend; only three scenes were included in Alfred Howard's The Beauties of Fielding, which collected passages from Fielding's works. A chapter on the play is included in Frederick Lawrence's Life of Fielding (1855), and it is mentioned by Leslie Stephen and Austin Dobson, who focus on what the play says about Grub Street and Fielding. George Saintsbury included The Author's Farce and two other plays in a Fielding collected edition of 1893, but ignored the others.[47]

Most later critics agreed with Dobson that the play primarily provides a commentary on events in Fielding's life, and marks Fielding's move from older forms of comedy to the new satire of his contemporaries.[48] Wilbur Lucius Cross, in 1918, believed the play revealed Fielding's farcical and burlesque talent and not regular drama.[49] In 1963, F. W. Bateson included the play in a list of "satirical extravaganzas."[50] Frederick Homes Dudden, writing in 1966, was clear that the revised version was undoubtedly an improvement on the original,[51] and that the puppet show in the third act "is a highly original satire on the theatrical and quasi-theatrical amusements of the day."[52] In the same year, Charles Woods argued that The Author's Farce was an integral part of Fielding's career.[53]

Comments made by Woods in the introduction to his edition of The Author's Farce influenced later critical interpretations of the play. Woods dismisses a political reading of the work, and emphasizes instead how it affected Fielding's career as a playwright.[54] Ian Donaldson claimed in 1970 that "The Author's Farce, like Fielding's other dramatic burlesques, turns out finally to be a good-natured romp."[55] In his 1975 comparison of Fielding's theatrical style and form, J. Paul Hunter argues that "Many of the literary and theatrical jibes are witty, but often the method seems essentially untheatrical in its slow timing and its failure to use dramatic conflict, as if Fielding were so anxious to comment directly that he gave little attention to setting up an occasion. Fielding's defense would surely have been that he intended to parody the bad theater of his contemporaries, and the defense is, in a sense, unanswerable, for the play leaves open the question of whether Fielding is responsible or Luckless is."[56] Later in 1979, Pat Rogers declares, "Few livelier theatrical occasions can ever have been seen than the original runs of The Author's Farce, with their mixture of broad comedy, personal satire, tuneful scenes and rapid action."[57]

Writing in 1988, Robert Hume gave it as his opinion that the literary structure of The Author's Farce is "ramshackle but effective",[58] although he also said that "Fielding's parody of recognition scenes is done with verve" and "the 'realistic' part of the show is a clever combination of the straightforward and the ironic."[59] In 1993, Martin and Ruthe Battestin argued that the play "was his [Fielding's] first experiment in the irregular comic modes ... where his true genius as a playwright at last found scope". They went on to say that Fielding offered audiences for the first time "a kind of pointed, inventive foolery", and that his talent for "ridicule and brisk dialogue", and for devising "absurd yet expressionistic plots", was unmatched even in 20th-century theatre.[60]

Harold Pagliaro, in 1998, pointed out that the play was Fielding's "first great success".[61] Catherine Ingrassi, in 2004, attributed the popularity of Fielding's play to his satirical attack on Haywood: "like Pope, Fielding profited from Haywood's accumulation of cultural credit. The literarily and sexually avaricious character of Mrs Novel depended on audience recognition of the literary type– woman writer– if not the specific model– Eliza Haywood."[62] That same year, Thomas Lockwood explained various aspects that make the play great, putting particular emphasis on the "musical third act", which he believed "shows a gift for brilliant theatrical arrangement". Lockwood was especially laudatory of the play's conclusion, and the ever increasing tempo of events following Murdertext's "explosive invasion".[63]

Cast

1730 cast

Play:[64]

- Harry Luckless – playwright, played by Mr. Mullart (William Mullart)

- Harriot Moneywood – daughter of Mrs. Moneywood, played by Miss Palms

- Mrs Moneywood – Luckless's landlady, played by Mrs. Mullart (Elizabeth Mullart)

- Witmore – played by Mr. Lacy (James Lacy)

- Marplay – played by Mr. Reynolds

- Sparkish – played by Mr. Stopler

- Bookweight – played by Mr. Jones

- Scarecrow – played by Mr. Marshal

- Dash – played by Mr. Hallam

- Quibble – played by Mr. Dove

- Blotpage – played by Mr. Wells junior

- Jack – Luckless's servant, played by Mr. Achurch

- Jack-Pudding – played by Mr. Reynolds

- Bantomite – played by Mr. Marshal

Internal puppet show:[65]

- Player – by Mr. Dove

- Constable – by Mr. Wells

- Murder-text – by Mr. Hallam

- Goddess of Nonsense – by Mrs. Mullart

- Charon – by Mr. Ayres

- Curry – by Mr. Dove

- A Poet – by Mr. W. Hallam

- Signior Opera – by Mr. Stopler

- Don Tragedio – by Mr. Marshal

- Sir Farcical Comick – by Mr. Davenport

- Dr. Orator – by Mr. Jones

- Monsieur Pantomime – by Mr. Knott

- Mrs. Novel – by Mrs. Martin

- Robgrave – by Mr. Harris

- Saylor – by Mr. Achurch

- Somebody – by Mr. Harris junior

- Nobody – by Mr. Wells junior

- Punch – by Mr. Hicks

- Lady Kingcall – by Miss Clarke

- Mrs. Cheat'em – by Mrs. Wind

- Mrs. Glass-rin – by Mrs. Blunt

- Prologue spoken by Mr. Jones[66]

- Epilogue spoken by four poets, a player and a cat

- 1st Poet – played by Mr. Jones

- 2nd Poet – played by Mr. Dove

- 3rd Poet – played by Mr. Marshall

- 4th Poet – played by Mr. Wells junior

- Player – played by Miss Palms

- Cat – played by Mrs. Martin

1734 altered cast

Play:[67]

- Index – unlisted actor

Internal puppet show:[68]

Footnotes

- ^ Comparing relative purchasing power of £13 in 1729 with 2008[30]

Notes

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 35–36

- ^ Pagliaro 1999 pp. 70–71

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 37

- ^ a b Pagliaro 1999 pp. 71–72

- ^ Campbell 1995 p. 33

- ^ Lockwood 2004 p. 282

- ^ Pagliaro 1999 p. 72

- ^ Hunter 1975 p. 54

- ^ Pagliaro 1999 pp. 69–70

- ^ a b Koon 1986 p. 123

- ^ Rivero 1989 p. 23

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 31–34

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 189

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 34–35

- ^ Pagliaro 1999 p. 71

- ^ Campbell 1995 pp. 32–34

- ^ Warner 1998 p. 242

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 38–41

- ^ Freeman 2002 pp. 59–63

- ^ Fielding 1967 p. 16

- ^ Rivero 1989 pp. 33–37

- ^ Warner 1998 p. 241

- ^ Freeman 2002 pp. 64–65

- ^ Ingrassia 2004 pp. 21–22

- ^ Roose-Evans 1977 p. 35

- ^ van der Voorde 1966 p. 96

- ^ Campbell 1995 pp. 33–34

- ^ Campbell 1995 pp. 32–36

- ^ Pagliaro 1999 p. 70

- ^ Officer, Lawrence H. (2009), Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present, MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 April 2010

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 72–73

- ^ Freeman 2002 pp. 62–63

- ^ Rawson 2008 p. 23

- ^ Hume 1988 p. 64

- ^ a b c Hume 1988 p. 63

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 189–190

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 205

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 192–193

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 194–196

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 196–197

- ^ Speaight 1990 p. 157

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 194–199

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 204–206

- ^ Rivero 1989 p. 31

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 194–195

- ^ Fielding 2004 qtd p. 204

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 205–206

- ^ Lockwood 2004 p. 206

- ^ Cross 1918 p. 80

- ^ Bateson 1963 pp. 121–126

- ^ Dudden 1966 p. 50

- ^ Dudden 1966 p. 54

- ^ Woods 1966 p. XV

- ^ Lockwood 2004 p. 207

- ^ Donaldson 1970 p. 194

- ^ Hunter 1975 p. 53

- ^ Rogers 1979 p. 49

- ^ Hume 1988 pp. 63–64

- ^ Hume 1988 pp. 64–65

- ^ Battestin and Battestin 1993 p. 83

- ^ Pagliaro 1998 p. 69

- ^ Ingrassia 2004 p. 106

- ^ Lockwood 2004 p. 212

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 227

- ^ Fielding 2004 pp. 227–228

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 222

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 304

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 305

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 297

- ^ Fielding 2004 p. 299

References

- Bateson, Frederick. English Comic Drama 1700–1750. Russell & Russell, 1963. OCLC 350284.

- Battestin, Martin, and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: A Life. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415014387

- Campbell, Jill. Natural Masques: Gender and Identity in Fielding's Plays and Novels. Stanford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0804723915

- Cross, Wilbur. The History of Henry Fielding. Yale University Press, 1918. OCLC 313644743.

- Donaldson, Ian. The World Upside Down: Comedy from Jonson to Fielding. Clarendon, 1970. ISBN 0198116942

- Dudden, F. Homes. Henry Fielding: His Life, Works and Times. Archon Books, 1966. OCLC 173325.

- Fielding, Henry. The Author's Farce. Edward Arnold, 1967. OCLC 16876561.

- Fielding, Henry. Plays Vol. 1 (1728–1731). Ed. Thomas Lockwood. Clarendon Press, 2004. ISBN 0199257892

- Freeman, Lisa. Character's Theatre. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002. ISBN 0812236394

- Hume, Robert. Fielding and the London Theater. Clarendon Press, 1988. ISBN 0198128649

- Hunter, J. Paul. Occasional Form. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. ISBN 0801816726

- Ingrassia, Catherine. Anti-Pamela and Shamela. Broadview Press, 2004. ISBN 155111383X

- Ingrassia, Catherine. Authorship, Commerce, and Gender in Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521630630

- Kinservik, Matthew. Disciplining Satire. Bucknell University Press, 2002. ISBN 0838755127

- Koon, Helene. Colley Cibber: A Biography. University Press of Kentucky, 1986. OCLC 301354330.

- Pagliaro, Harold. Henry Fielding: A Literary Life. St Martin's Press, 1998. ISBN 0312210329

- Rawson, Claude. Henry Fielding (1707–1754). University of Delaware Press, 2008. ISBN 9780874139310

- Rivero, Albert. The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career. University Press of Virginia, 1989. ISBN 0813912288

- Rogers, Pat. Henry Fielding, A Biography. Scribner, 1979. ISBN 0684162644

- Roose-Evans, James. London Theatre: From the Globe to the National. Phaidon, 1977. ISBN 071481766X

- Speaight, George. The History of the English Puppet Theatre. Southern Illinois University Press, 1990. ISBN 0809316064

- van der Voorde, Frans Pieter. Henry Fielding, Critic and Satirist. Haskell House Publishers, 1966 [1931]

- Warner, William B. Licensing Entertainment: The Elevation of Novel Reading in Britain, 1684–1750. University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520201809

- Woods, Charles. "Introduction" in The Author's Farce. University of Nebraska Press, 1966. OCLC 355476.