Systema Naturae: Difference between revisions

→Overview: ce |

→Overview: copyedit |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Linnaeus (later known as "Carl von Linné", after his ennoblement in 1761<ref>W.T. Stearn, An introduction to the Species Plantarum and cognate botanical works of Linnaeus, in: Species Plantarum, 1957 Ray Society facsimile edition, p. 14</ref>) published the first edition of ''Systema Naturae'' in the year 1735, during his stay in the [[Netherlands]]. As customary for the [[scientific literature]] of its day, the book was published in [[Latin]]. In it, he outlines his ideas for the hierarchical classification of the natural world, dividing it into the [[Animal|animal kingdom]] (''Regnum animale''), the [[Plantae|plant kingdom]] (''Regnum vegetabile'') and the "[[mineral|mineral kingdom]]" (''Regnum lapideum''). |

Linnaeus (later known as "Carl von Linné", after his ennoblement in 1761<ref>W.T. Stearn, An introduction to the Species Plantarum and cognate botanical works of Linnaeus, in: Species Plantarum, 1957 Ray Society facsimile edition, p. 14</ref>) published the first edition of ''Systema Naturae'' in the year 1735, during his stay in the [[Netherlands]]. As customary for the [[scientific literature]] of its day, the book was published in [[Latin]]. In it, he outlines his ideas for the hierarchical classification of the natural world, dividing it into the [[Animal|animal kingdom]] (''Regnum animale''), the [[Plantae|plant kingdom]] (''Regnum vegetabile'') and the "[[mineral|mineral kingdom]]" (''Regnum lapideum''). |

||

At the time of Linnaeus only about 10,000 species of organisms were recognised by science, about 6,000 species of plants and 4,236 species of animals.<ref>[[William T. Stearn|Stearn, William T.]]1959. "The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology". ''Systematic Zoology'' '''8''': 4–22.</ref> |

At the time of Linnaeus only about 10,000 species of organisms were recognised by science, about 6,000 species of plants and 4,236 species of animals. Even in 1753 he believed that the number of species of plants in the whole world would hardly reach 10,000; in his whole career he named about 7,700 species of flowering plants.<ref>[[William T. Stearn|Stearn, William T.]]1959. "The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology". ''Systematic Zoology'' '''8''': 4–22.</ref> |

||

The classification of the plant kingdom in the book was not one meant to reflect the actual order of nature{{Clarify me|reason=meaning perhaps that the system turned out to yield groups of plants that were only superficially similar?|date=May 2009}} but to organize it in a fashion convenient for humans{{Citation needed|reason=How do we know Linnaeus did not consider this classification scheme to reflect the natural order?|date=May 2009}}: it followed Linnaeus' new [[Linnaean taxonomy#For plants|sexual system]] where species with the same number of [[stamen]]s were treated in the same group. Linnaeus believed that he was classifying [[God]]'s creation and was not trying to express any deeper relationships. He is frequently quoted to have said ''God created, Linnaeus organized''. The classification of animals was more natural. For instance, [[human]]s were for the first time placed together with other [[primate]]s, as [[Anthropomorpha]]. |

The classification of the plant kingdom in the book was not one meant to reflect the actual order of nature{{Clarify me|reason=meaning perhaps that the system turned out to yield groups of plants that were only superficially similar?|date=May 2009}} but to organize it in a fashion convenient for humans{{Citation needed|reason=How do we know Linnaeus did not consider this classification scheme to reflect the natural order?|date=May 2009}}: it followed Linnaeus' new [[Linnaean taxonomy#For plants|sexual system]] where species with the same number of [[stamen]]s were treated in the same group. Linnaeus believed that he was classifying [[God]]'s creation and was not trying to express any deeper relationships. He is frequently quoted to have said ''God created, Linnaeus organized''. The classification of animals was more natural. For instance, [[human]]s were for the first time placed together with other [[primate]]s, as [[Anthropomorpha]]. |

||

Revision as of 08:44, 1 September 2010

The book Systema Naturæ (commonly written Systema Naturae without the ligature æ in modern English) was one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carolus Linnaeus. The first edition was published in 1735. The full title of the 10th edition, which was certainly the most important one, was Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis or translated: "System of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places".

The tenth edition of this book is considered the starting point of zoological nomenclature.[1]

Overview

Linnaeus (later known as "Carl von Linné", after his ennoblement in 1761[2]) published the first edition of Systema Naturae in the year 1735, during his stay in the Netherlands. As customary for the scientific literature of its day, the book was published in Latin. In it, he outlines his ideas for the hierarchical classification of the natural world, dividing it into the animal kingdom (Regnum animale), the plant kingdom (Regnum vegetabile) and the "mineral kingdom" (Regnum lapideum).

At the time of Linnaeus only about 10,000 species of organisms were recognised by science, about 6,000 species of plants and 4,236 species of animals. Even in 1753 he believed that the number of species of plants in the whole world would hardly reach 10,000; in his whole career he named about 7,700 species of flowering plants.[3]

The classification of the plant kingdom in the book was not one meant to reflect the actual order of nature[clarification needed] but to organize it in a fashion convenient for humans[citation needed]: it followed Linnaeus' new sexual system where species with the same number of stamens were treated in the same group. Linnaeus believed that he was classifying God's creation and was not trying to express any deeper relationships. He is frequently quoted to have said God created, Linnaeus organized. The classification of animals was more natural. For instance, humans were for the first time placed together with other primates, as Anthropomorpha.

In view of the popularity of the work, Linnaeus kept publishing new and ever-expanding editions, growing from eleven very large pages in the first edition (1735) to three thousand pages in the final and thirteenth edition (1767). Also, as the work progressed he made changes: in the first edition whales were classified as fishes, following the work of Linnaeus' friend and "father of ichthyology" Peter Artedi; in the 10th edition, published in 1758, whales were moved into the mammal class. In this same edition he introduced two part names (see binomen) for animal species, something he had done for plant species (see binary name) in the 1753 publication of Species Plantarum. The system eventually developed into modern Linnaean taxonomy, a hierarchically organized biological classification.

Taxonomy

In his Imperium Naturæ, Linnaeus established three kingdoms, namely Regnum Animale, Regnum Vegetabile and Regnum Lapideum. This approach, the Animal, Vegetable and Mineral Kingdoms, survives until today in the popular mind, notably in the form of parlour games: "Is it animal, vegetable or mineral?". The classification was based on 5 levels: Kingdom, class, order, genus and species. While species and genus was seen as God-given (or "natural"), the three higher levels were seen by Linnaeus as constructs. The concept behind the set ranks being applied to all groups was to make a system that was easy to remember and navigate in, a task in which he must be said to have succeeded.

The work of Linnaeus had a huge impact on science; it was indispensable as a foundation for biological nomenclature, now regulated by the Nomenclature Codes. Two of his works, the first edition of the Species Plantarum (1753) for plants and the tenth edition of the Systema Naturæ (1758) are accepted among the starting points of nomenclature; his binomials (names for species) and his generic names take priority over those of others. However, the impact he had on science was not because of the value of his taxonomy. His taxonomy was not particularly notable, but Linnaeus' talent for attracting skillful young students and sending them abroad to collect made his works far more influential than that of his contemporaries.[4] At the close of the 18th century, his system had effectively become the standard system for biological classification.

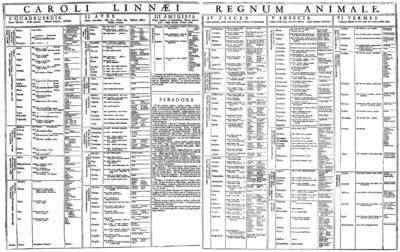

The Animal Kingdom

Only in the Animal Kingdom is the higher taxonomy of Linnaeus still more or less recognizable and some of these names are still in use, but usually not quite for the same groups as used by Linnaeus. He divided the Animal Kingdom into six classes, in the tenth edition, of 1758, these were:

- Classis 1. QUADRUPEDIA, mammals. In the first edition whales and the West Indian Manatee were classified among the fishes.

- Classis 2. AVES, birds. Linnaeus was the first to remove bats from the birds and classify them under mammals.

- Classis 3. AMPHIBIA, amphibians, reptiles, and assorted fishes that are not of Osteichthyes.

- Classis 4. PISCES, bony fishes, among them spiny-finned fishes (Perciformes) as a separate order.

- Classis 5. INSECTA, insects; really arthropods. Included crustaceans, arachnids, & myriapods as one order.

- Classis 6. VERMES, miss-matched grouping of invertebrates, roughly divided into "worms", molluscs and hard shelled organisms like echinodermates.

The Plant Kingdom

His orders and classes of plants, according to his Systema Sexuale, were never intended to represent natural groups (as opposed to his ordines naturales in his Philosophia Botanica) but only for use in identification. They were used in that sense well into the nineteenth century.

The Linnaean classes for plants, in the Sexual System, were:

- Classis 1. Monandria

- Classis 2. Diandria

- Classis 3. Triandria

- Classis 4. Tetrandria

- Classis 5. Pentandria

- Classis 6. Hexandria

- Classis 7. Heptandria

- Classis 8. Octandria

- Classis 9. Enneandria

- Classis 10. Decandria

- Classis 11. Dodecandria

- Classis 12. Icosandria

- Classis 13. Polyandra

- Classis 14. Didynamia

- Classis 15. Tetradynamia

- Classis 16. Monadelphia

- Classis 17. Diadelphia

- Classis 18. Polyadelphia

- Classis 19. Syngenesia

- Classis 20. Gynandria

- Classis 21. Monoecia

- Classis 22. Dioecia

- Classis 23. Polygamia

- Classis 24. Cryptogamia

The Mineral Kingdoms

His taxonomy of minerals has dropped long since from use. In the tenth edition, 1758, of the Systema Naturæ, the Linnaean classes were:

- Classis 1. PETRÆ (rocks)

- Classis 2. MINERÆ (minerals and ores)

- Classis 3. FOSSILIA (fossils and aggregates)[5]

See Also

References

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th edition ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). Retrieved 2008-09-22.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ W.T. Stearn, An introduction to the Species Plantarum and cognate botanical works of Linnaeus, in: Species Plantarum, 1957 Ray Society facsimile edition, p. 14

- ^ Stearn, William T.1959. "The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology". Systematic Zoology 8: 4–22.

- ^ Sörlin, F. (2004): Linné och hans apostlar. Natur och Kultur/Fakta, Örebro, Sweden

- ^ "Linnaeus as a minerologist". Linné on line. Uppsala University. 2008.

External links

- Linné online

- 10th edition (2 volumes) online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- 12th edition (in three volumes) online at gallica

- 13th edition (Volume I, 532 pages) online at Google Book Search