Quicksort: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 479623620 by 117.201.68.115 (talk) |

Added a link to a book section |

||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

* [http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~panos/java/Quicksort/index.html Interactive Tutorial for Quicksort] |

* [http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~panos/java/Quicksort/index.html Interactive Tutorial for Quicksort] |

||

* [http://www.yorku.ca/sychen/research/sorting/index.html Quicksort applet] with "level-order" recursive calls to help improve algorithm analysis |

* [http://www.yorku.ca/sychen/research/sorting/index.html Quicksort applet] with "level-order" recursive calls to help improve algorithm analysis |

||

* [http://opendatastructures.org/versions/edition-0.1c/ods-java/node56.html#SECTION001412000000000000000 Open Data Structures - Section 11.1.2 - Quicksort] |

|||

* [http://fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/staff/wohlgemuth/java/quicksort Multidimensional quicksort in Java] |

* [http://fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/staff/wohlgemuth/java/quicksort Multidimensional quicksort in Java] |

||

* [http://en.literateprograms.org/Category:Quicksort Literate implementations of Quicksort in various languages] on LiteratePrograms |

* [http://en.literateprograms.org/Category:Quicksort Literate implementations of Quicksort in various languages] on LiteratePrograms |

||

Revision as of 14:25, 2 March 2012

Visualization of the quicksort algorithm. The horizontal lines are pivot values. | |

| Class | Sorting algorithm |

|---|---|

| Worst-case performance | O(n2) |

| Best-case performance | O(n log n) |

| Average performance | O(n log n) |

| Worst-case space complexity | O(n) auxiliary (naive) O(log n) auxiliary (Sedgewick 1978) |

| Optimal | No |

Quicksort is a sorting algorithm developed by Tony Hoare that, on average, makes comparisons to sort n items. In the worst case, it makes comparisons, though this behavior is rare. Quicksort is often faster in practice than other algorithms.[1] Additionally, quicksort's sequential and localized memory references work well with a cache. Quicksort can be implemented with an in-place partitioning algorithm, so the entire sort can be done with only additional space.[2]

Quicksort (also known as "partition-exchange sort") is a comparison sort and, in efficient implementations, is not a stable sort.

History

The quicksort algorithm was developed in 1960 by Tony Hoare while in the Soviet Union, as a visiting student at Moscow State University. At that time, Hoare worked in a project on machine translation for the National Physical Laboratory. He developed the algorithm in order to sort the words to be translated, to make them more easily matched to an already-sorted Russian-to-English dictionary that was stored on magnetic tape.[3]

Algorithm

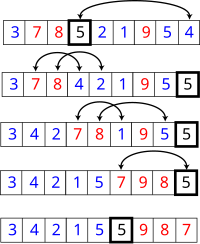

Quicksort is a divide and conquer algorithm. Quicksort first divides a large list into two smaller sub-lists: the low elements and the high elements. Quicksort can then recursively sort the sub-lists.

The steps are:

- Pick an element, called a pivot, from the list.

- Reorder the list so that all elements with values less than the pivot come before the pivot, while all elements with values greater than the pivot come after it (equal values can go either way). After this partitioning, the pivot is in its final position. This is called the partition operation.

- Recursively sort the sub-list of lesser elements and the sub-list of greater elements.

The base case of the recursion are lists of size zero or one, which never need to be sorted.

Simple version

In simple pseudocode, the algorithm might be expressed as this:

function quicksort('array')

if length('array') ≤ 1

return 'array' // an array of zero or one elements is already sorted

select and remove a pivot value 'pivot' from 'array'

create empty lists 'less' and 'greater'

for each 'x' in 'array'

if 'x' ≤ 'pivot' then append 'x' to 'less'

else append 'x' to 'greater'

return concatenate(quicksort('less'), 'pivot', quicksort('greater')) // two recursive calls

Notice that we only examine elements by comparing them to other elements. This makes quicksort a comparison sort. This version is also a stable sort (assuming that the "for each" method retrieves elements in original order, and the pivot selected is the last among those of equal value).

The correctness of the partition algorithm is based on the following two arguments:

- At each iteration, all the elements processed so far are in the desired position: before the pivot if less than the pivot's value, after the pivot if greater than the pivot's value (loop invariant).

- Each iteration leaves one fewer element to be processed (loop variant).

The correctness of the overall algorithm can be proven via induction: for zero or one element, the algorithm leaves the data unchanged; for a larger data set it produces the concatenation of two parts, elements less than the pivot and elements greater than it, themselves sorted by the recursive hypothesis.

In-place version

The disadvantage of the simple version above is that it requires O(n) extra storage space, which is as bad as merge sort. The additional memory allocations required can also drastically impact speed and cache performance in practical implementations. There is a more complex version which uses an in-place partition algorithm and can achieve the complete sort using O(log n) space (not counting the input) on average (for the call stack). We start with a partition function:

// left is the index of the leftmost element of the array

// right is the index of the rightmost element of the array (inclusive)

// number of elements in subarray = right-left+1

function partition(array, 'left', 'right', 'pivotIndex')

'pivotValue' := array['pivotIndex']

swap array['pivotIndex'] and array['right'] // Move pivot to end

'storeIndex' := 'left'

for 'i' from 'left' to 'right' - 1 // left ≤ i < right

if array['i'] < 'pivotValue'

swap array['i'] and array['storeIndex']

'storeIndex' := 'storeIndex' + 1

swap array['storeIndex'] and array['right'] // Move pivot to its final place

return 'storeIndex'

|

This is the in-place partition algorithm. It partitions the portion of the array between indexes left and right, inclusively, by moving all elements less than array[pivotIndex] before the pivot, and the equal or greater elements after it. In the process it also finds the final position for the pivot element, which it returns. It temporarily moves the pivot element to the end of the subarray, so that it doesn't get in the way. Because it only uses exchanges, the final list has the same elements as the original list. Notice that an element may be exchanged multiple times before reaching its final place. Also, in case of pivot duplicates in the input array, they can be spread across the right subarray, in any order. This doesn't represent a partitioning failure, as further sorting will reposition and finally "glue" them together.

This form of the partition algorithm is not the original form; multiple variations can be found in various textbooks, such as versions not having the storeIndex. However, this form is probably the easiest to understand.

Once we have this, writing quicksort itself is easy:

function quicksort(array, 'left', 'right')

// If the list has 2 or more items

if 'left' < 'right'

// See "Choice of pivot" section below for possible choices

choose any 'pivotIndex' such that 'left' ≤ 'pivotIndex' ≤ 'right'

// Get lists of bigger and smaller items and final position of pivot

'pivotNewIndex' := partition(array, 'left', 'right', 'pivotIndex')

// Recursively sort elements smaller than the pivot

quicksort(array, 'left', 'pivotNewIndex' - 1)

// Recursively sort elements at least as big as the pivot

quicksort(array, 'pivotNewIndex' + 1, 'right')

|

Each recursive call to this quicksort function reduces the size of the array being sorted by at least one element, since in each invocation the element at pivotNewIndex is placed in its final position. Therefore, this algorithm is guaranteed to terminate after at most n recursive calls. However, since partition reorders elements within a partition, this version of quicksort is not a stable sort.

Implementation issues

Choice of pivot

In very early versions of quicksort, the leftmost element of the partition would often be chosen as the pivot element. Unfortunately, this causes worst-case behavior on already sorted arrays, which is a rather common use-case. The problem was easily solved by choosing either a random index for the pivot, choosing the middle index of the partition or (especially for longer partitions) choosing the median of the first, middle and last element of the partition for the pivot (as recommended by R. Sedgewick).[4][5]

Selecting a pivot element is also complicated by the existence of integer overflow. If the boundary indices of the subarray being sorted are sufficiently large, the naïve expression for the middle index, (left + right)/2, will cause overflow and provide an invalid pivot index. This can be overcome by using, for example, left + (right-left)/2 to index the middle element, at the cost of more complex arithmetic. Similar issues arise in some other methods of selecting the pivot element.

Optimizations

Two other important optimizations, also suggested by R. Sedgewick, as commonly acknowledged, and widely used in practice are:[6][7][8]

- To make sure at most O(log N) space is used, recurse first into the smaller half of the array, and use a tail call to recurse into the other.

- Use insertion sort, which has a smaller constant factor and is thus faster on small arrays, for invocations on such small arrays (i.e. where the length is less than a threshold t determined experimentally). This can be implemented by leaving such arrays unsorted and running a single insertion sort pass at the end, because insertion sort handles nearly sorted arrays efficiently. A separate insertion sort of each small segment as they are identified adds the overhead of starting and stopping many small sorts, but avoids wasting effort comparing keys across the many segment boundaries, which keys will be in order due to the workings of the quicksort process. It also improves the cache use.

Parallelization

Like merge sort, quicksort can also be parallelized due to its divide-and-conquer nature. Individual in-place partition operations are difficult to parallelize, but once divided, different sections of the list can be sorted in parallel. The following is a straightforward approach: If we have processors, we can divide a list of elements into sublists in O(n) average time, then sort each of these in average time. Ignoring the O(n) preprocessing and merge times, this is linear speedup. If the split is blind, ignoring the values, the merge naïvely costs O(n). If the split partitions based on a succession of pivots, it is tricky to parallelize and naïvely costs O(n). Given O(log n) or more processors, only O(n) time is required overall, whereas an approach with linear speedup would achieve O(log n) time for overall.

One advantage of this simple parallel quicksort over other parallel sort algorithms is that no synchronization is required, but the disadvantage is that sorting is still O(n) and only a sublinear speedup of O(log n) is achieved. A new thread is started as soon as a sublist is available for it to work on and it does not communicate with other threads. When all threads complete, the sort is done.

Other more sophisticated parallel sorting algorithms can achieve even better time bounds.[9] For example, in 1991 David Powers described a parallelized quicksort (and a related radix sort) that can operate in O(log n) time on a CRCW PRAM with n processors by performing partitioning implicitly.[10]

Formal analysis

From the initial description it's not obvious that quicksort takes O(n log n) time on average. It's not hard to see that the partition operation, which simply loops over the elements of the array once, uses O(n) time. In versions that perform concatenation, this operation is also O(n).

In the best case, each time we perform a partition we divide the list into two nearly equal pieces. This means each recursive call processes a list of half the size. Consequently, we can make only nested calls before we reach a list of size 1. This means that the depth of the call tree is . But no two calls at the same level of the call tree process the same part of the original list; thus, each level of calls needs only O(n) time all together (each call has some constant overhead, but since there are only O(n) calls at each level, this is subsumed in the O(n) factor). The result is that the algorithm uses only O(n log n) time.

An alternative approach is to set up a recurrence relation for the T(n) factor, the time needed to sort a list of size . Because a single quicksort call involves O(n) factor work plus two recursive calls on lists of size in the best case, the relation would be.

The master theorem tells us that T(n) = O(n log n).

In fact, it's not necessary to divide the list this precisely; even if each pivot splits the elements with 99% on one side and 1% on the other (or any other fixed fraction), the call depth is still limited to , so the total running time is still O(n log n).

In the worst case, however, the two sublists have size 1 and (for example, if the array consists of the same element by value), and the call tree becomes a linear chain of nested calls. The th call does work, and . The recurrence relation is:

This is the same relation as for insertion sort and selection sort, and it solves to . Given knowledge of which comparisons are performed by the sort, there are adaptive algorithms that are effective at generating worst-case input for quicksort on-the-fly, regardless of the pivot selection strategy.[11]

Randomized quicksort expected complexity

Randomized quicksort has the desirable property that, for any input, it requires only O(n log n) expected time (averaged over all choices of pivots). But what makes random pivots a good choice?

Suppose we sort the list and then divide it into four parts. The two parts in the middle will contain the best pivots; each of them is larger than at least 25% of the elements and smaller than at least 25% of the elements. If we could consistently choose an element from these two middle parts, we would only have to split the list at most times before reaching lists of size 1, yielding an O(n log n) algorithm.

A random choice will only choose from these middle parts half the time. However, this is good enough. Imagine that you are flipping a coin over and over until you get k heads. Although this could take a long time, on average only 2k flips are required, and the chance that you won't get heads after flips is highly improbable. By the same argument, quicksort's recursion will terminate on average at a call depth of only . But if its average call depth is O(log n), and each level of the call tree processes at most elements, the total amount of work done on average is the product, O(n log n). Note that the algorithm does not have to verify that the pivot is in the middle half—if we hit it any constant fraction of the times, that is enough for the desired complexity.

The outline of a formal proof of the O(n log n) expected time complexity follows. Assume that there are no duplicates as duplicates could be handled with linear time pre- and post-processing, or considered cases easier than the analyzed. Choosing a pivot, uniformly at random from 0 to n-1, is then equivalent to choosing the size of one particular partition, uniformly at random from 0 to n-1. With this observation, the continuation of the proof is analogous to the one given in the average complexity section.

Average complexity

Even if pivots aren't chosen randomly, quicksort still requires only O(n log n) time averaged over all possible permutations of its input. Because this average is simply the sum of the times over all permutations of the input divided by n factorial, it's equivalent to choosing a random permutation of the input. When we do this, the pivot choices are essentially random, leading to an algorithm with the same running time as randomized quicksort.

More precisely, the average number of comparisons over all permutations of the input sequence can be estimated accurately by solving the recurrence relation:

Here, is the number of comparisons the partition uses. Since the pivot is equally likely to fall anywhere in the sorted list order, the sum is averaging over all possible splits.

This means that, on average, quicksort performs only about 39% worse than in its best case. In this sense it is closer to the best case than the worst case. Also note that a comparison sort cannot use less than comparisons on average to sort items (as explained in the article Comparison sort) and in case of large , Stirling's approximation yields , so quicksort is not much worse than an ideal comparison sort. This fast average runtime is another reason for quicksort's practical dominance over other sorting algorithms.

Space complexity

The space used by quicksort depends on the version used.

The in-place version of quicksort has a space complexity of O(log n), even in the worst case, when it is carefully implemented using the following strategies:

- in-place partitioning is used. This unstable partition requires O(1) space.

- After partitioning, the partition with the fewest elements is (recursively) sorted first, requiring at most O(log n) space. Then the other partition is sorted using tail recursion or iteration, which doesn't add to the call stack. This idea, as discussed above, was described by R. Sedgewick, and keeps the stack depth bounded by O(log n).[4][5]

Quicksort with in-place and unstable partitioning uses only constant additional space before making any recursive call. Quicksort must store a constant amount of information for each nested recursive call. Since the best case makes at most O(log n) nested recursive calls, it uses O(log n) space. However, without Sedgewick's trick to limit the recursive calls, in the worst case quicksort could make O(n) nested recursive calls and need O(n) auxilliary space.

From a bit complexity viewpoint, variables such as left and right do not use constant space; it takes O(log n) bits to index into a list of n items. Because there are such variables in every stack frame, quicksort using Sedgewick's trick requires bits of space. This space requirement isn't too terrible, though, since if the list contained distinct elements, it would need at least O(n log n) bits of space.

Another, less common, not-in-place, version of quicksort uses O(n) space for working storage and can implement a stable sort. The working storage allows the input array to be easily partitioned in a stable manner and then copied back to the input array for successive recursive calls. Sedgewick's optimization is still appropriate.

Selection-based pivoting

A selection algorithm chooses the kth smallest of a list of numbers; this is an easier problem in general than sorting. One simple but effective selection algorithm works nearly in the same manner as quicksort, except that instead of making recursive calls on both sublists, it only makes a single tail-recursive call on the sublist which contains the desired element. This small change lowers the average complexity to linear or O(n) time, and makes it an in-place algorithm. A variation on this algorithm brings the worst-case time down to O(n) (see selection algorithm for more information).

Conversely, once we know a worst-case O(n) selection algorithm is available, we can use it to find the ideal pivot (the median) at every step of quicksort, producing a variant with worst-case O(n log n) running time. In practical implementations, however, this variant is considerably slower on average.

Another variant is to choose the Median of Medians as the pivot element instead of the median itself for partitioning the elements. While maintaining the asymptotically optimal run time complexity of O(n log n) (by preventing worst case partitions), it is also considerably faster than the variant that chooses the median as pivot.

Variants

There are four well known variants of quicksort:

- Balanced quicksort: choose a pivot likely to represent the middle of the values to be sorted, and then follow the regular quicksort algorithm.

- External quicksort: The same as regular quicksort except the pivot is replaced by a buffer. First, read the M/2 first and last elements into the buffer and sort them. Read the next element from the beginning or end to balance writing. If the next element is less than the least of the buffer, write it to available space at the beginning. If greater than the greatest, write it to the end. Otherwise write the greatest or least of the buffer, and put the next element in the buffer. Keep the maximum lower and minimum upper keys written to avoid resorting middle elements that are in order. When done, write the buffer. Recursively sort the smaller partition, and loop to sort the remaining partition. This is a kind of three-way quicksort in which the middle partition (buffer) represents a sorted subarray of elements that are approximately equal to the pivot.

- Three-way radix quicksort (developed by Sedgewick and also known as multikey quicksort): is a combination of radix sort and quicksort. Pick an element from the array (the pivot) and consider the first character (key) of the string (multikey). Partition the remaining elements into three sets: those whose corresponding character is less than, equal to, and greater than the pivot's character. Recursively sort the "less than" and "greater than" partitions on the same character. Recursively sort the "equal to" partition by the next character (key). Given we sort using bytes or words of length W bits, the best case is O(KN) and the worst case O(2KN) or at least O(N2) as for standard quicksort, given for unique keys N<2K, and K is a hidden constant in all standard comparison sort algorithms including quicksort. This is a kind of three-way quicksort in which the middle partition represents a (trivially) sorted subarray of elements that are exactly equal to the pivot.

- Quick radix sort (also developed by Powers as a o(K) parallel PRAM algorithm). This is again a combination of radix sort and quicksort but the quicksort left/right partition decision is made on successive bits of the key, and is thus O(KN) for N K-bit keys. Note that all comparison sort algorithms effectively assume an ideal K of O(logN) as if k is smaller we can sort in O(N) using a hash table or integer sorting, and if K >> logN but elements are unique within O(logN) bits, the remaining bits will not be looked at by either quicksort or quick radix sort, and otherwise all comparison sorting algorithms will also have the same overhead of looking through O(K) relatively useless bits but quick radix sort will avoid the worst case O(N2) behaviours of standard quicksort and quick radix sort, and will be faster even in the best case of those comparison algorithms under these conditions of uniqueprefix(K) >> logN. See Powers [12] for further discussion of the hidden overheads in comparison, radix and parallel sorting.

Comparison with other sorting algorithms

Quicksort is a space-optimized version of the binary tree sort. Instead of inserting items sequentially into an explicit tree, quicksort organizes them concurrently into a tree that is implied by the recursive calls. The algorithms make exactly the same comparisons, but in a different order. An often desirable property of a sorting algorithm is stability - that is the order of elements that compare equal is not changed, allowing controlling order of multikey tables (e.g. directory or folder listings) in a natural way. This property is hard to maintain for in situ (or in place) quicksort (that uses only constant additional space for pointers and buffers, and logN additional space for the management of explicit or implicit recursion). For variant quicksorts involving extra memory due to representations using pointers (e.g. lists or trees) or files (effectively lists), it is trivial to maintain stability. The more complex, or disk-bound, data structures tend to increase time cost, in general making increasing use of virtual memory or disk.

The most direct competitor of quicksort is heapsort. Heapsort's worst-case running time is always O(n log n). But, heapsort is assumed to be on average somewhat slower than standard in-place quicksort. This is still debated and in research, with some publications indicating the opposite.[13][14] Introsort is a variant of quicksort that switches to heapsort when a bad case is detected to avoid quicksort's worst-case running time. If it is known in advance that heapsort is going to be necessary, using it directly will be faster than waiting for introsort to switch to it.

Quicksort also competes with mergesort, another recursive sort algorithm but with the benefit of worst-case O(n log n) running time. Mergesort is a stable sort, unlike standard in-place quicksort and heapsort, and can be easily adapted to operate on linked lists and very large lists stored on slow-to-access media such as disk storage or network attached storage. Like mergesort, quicksort can be implemented as an in-place stable sort [15], but this is seldom done. Although quicksort can be written to operate on linked lists, it will often suffer from poor pivot choices without random access. The main disadvantage of mergesort is that, when operating on arrays, efficient implementations require O(n) auxiliary space, whereas the variant of quicksort with in-place partitioning and tail recursion uses only O(log n) space. (Note that when operating on linked lists, mergesort only requires a small, constant amount of auxiliary storage.)

Bucket sort with two buckets is very similar to quicksort; the pivot in this case is effectively the value in the middle of the value range, which does well on average for uniformly distributed inputs.

See also

Notes

- ^ S. S. Skiena, The Algorithm Design Manual, Second Edition, Springer, 2008, p. 129

- ^ "Data structures and algorithm: Quicksort". Auckland University.

- ^ "An Interview with C.A.R. Hoare". Communications of the ACM, March 2009 ("premium content").

- ^ a b R. Sedgewick, Algorithms in C, Parts 1-4: Fundamentals, Data Structures, Sorting, Searching, 3rd Edition, Addison-Wesley

- ^ a b R. Sedgewick, Implementing quicksort programs, Comm. ACM, 21(10):847-857, 1978.

- ^ qsort.c in GNU libc: [1], [2]

- ^ http://home.tiscalinet.ch/t_wolf/tw/ada95/sorting/index.html

- ^ http://www.ugrad.cs.ubc.ca/~cs260/chnotes/ch6/Ch6CovCompiled.html

- ^ R.Miller, L.Boxer, Algorithms Sequential & Parallel, A Unified Approach, Prentice Hall, NJ, 2006

- ^ David M. W. Powers, Parallelized Quicksort and Radixsort with Optimal Speedup, Proceedings of International Conference on Parallel Computing Technologies. Novosibirsk. 1991.

- ^ M. D. McIlroy. A Killer Adversary for Quicksort. Software Practice and Experience: vol.29, no.4, 341–344. 1999. At Citeseer

- ^ David M. W. Powers, Parallel Unification: Practical Complexity, Australasian Computer Architecture Workshop, Flinders University, January 1995

- ^ Hsieh, Paul (2004). "Sorting revisited". www.azillionmonkeys.com. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ MacKay, David (1 December 2005). "Heapsort, Quicksort, and Entropy". users.aims.ac.za/~mackay. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ A Java implementation of in-place stable quicksort

References

- R. Sedgewick, Implementing quicksort programs, Comm. ACM, 21(10):847-857, 1978. Implementing Quicksort Programs

- Brian C. Dean, "A Simple Expected Running Time Analysis for Randomized 'Divide and Conquer' Algorithms." Discrete Applied Mathematics 154(1): 1-5. 2006.

- Hoare, C. A. R. "Partition: Algorithm 63," "Quicksort: Algorithm 64," and "Find: Algorithm 65." Comm. ACM 4(7), 321-322, 1961

- Hoare, C. A. R. "Quicksort." Computer Journal 5 (1): 10-15. (1962). (Reprinted in Hoare and Jones: Essays in computing science, 1989.)

- David Musser. Introspective Sorting and Selection Algorithms, Software Practice and Experience vol 27, number 8, pages 983-993, 1997

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3: Sorting and Searching, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89685-0. Pages 113–122 of section 5.2.2: Sorting by Exchanging.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Chapter 7: Quicksort, pp. 145–164.

- A. LaMarca and R. E. Ladner. "The Influence of Caches on the Performance of Sorting." Proceedings of the Eighth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, 1997. pp. 370–379.

- Faron Moller. Analysis of Quicksort. CS 332: Designing Algorithms. Department of Computer Science, Swansea University.

- Conrado Martínez and Salvador Roura, Optimal sampling strategies in quicksort and quickselect. SIAM J. Computing 31(3):683-705, 2001.

- Jon L. Bentley and M. Douglas McIlroy, Engineering a Sort Function, Software—Practice and Experience, Vol. 23(11), 1249–1265, 1993

External links

- Animated Sorting Algorithms: Quick Sort – graphical demonstration and discussion of quick sort

- Animated Sorting Algorithms: 3-Way Partition Quick Sort – graphical demonstration and discussion of 3-way partition quick sort

- Interactive Tutorial for Quicksort

- Quicksort applet with "level-order" recursive calls to help improve algorithm analysis

- Open Data Structures - Section 11.1.2 - Quicksort

- Multidimensional quicksort in Java

- Literate implementations of Quicksort in various languages on LiteratePrograms

- A colored graphical Java applet which allows experimentation with initial state and shows statistics